Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(8):1795-1802

A more recent article on adult acute rhinosinusitis is available.

See related patient information handout on caring for acute sinusitis, written by Elizabeth Smoots, M.D.

Acute bacterial sinusitis usually occurs following an upper respiratory infection that results in obstruction of the osteomeatal complex, impaired mucociliary clearance and overproduction of secretions. The diagnosis is based on the patient's history of a biphasic illness (“double sickening”), purulent rhinorrhea, maxillary toothache, pain on leaning forward, pain with a unilateral prominence and a poor response to decongestant therapy. Radiographs and computed tomographic scans of the sinuses generally are not useful in making the initial diagnosis. Since sinusitis is self-limited in 40 to 50 percent of patients, the expensive, newer-generation antibiotics should not be used as first-line therapy. First-line antibiotics such as amoxicillin or trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole are as effective in the treatment of sinusitis as the more expensive antibiotics. Little evidence supports the use of adjunctive treatments such as nasal corticosteroids and systemic decongestants. Patients with recurrent or chronic sinusitis require referral to an otolaryngologist for consideration of functional endoscopic sinus surgery.

Sinusitis is a common ailment: 16 percent of the U.S. population reports a diagnosis of sinusitis annually, accounting for 16 million office visits.1 Public interest in sinusitis is exemplified by a 1997 Internet search using Alta Vista, which found 4,960 matches. Furthermore, sinusitis is a costly disorder: about $2 billion is spent annually on medications to treat nasal and sinus problems.1 The National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS) lists sinusitis as the fifth most common diagnosis for which an antibiotic is prescribed.2

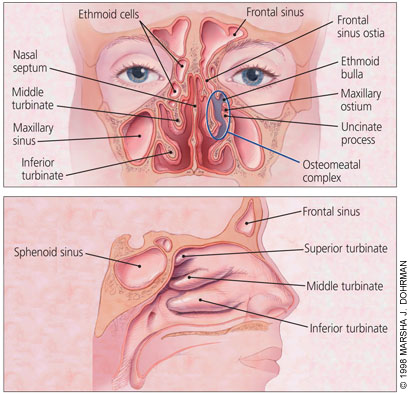

Sinus Anatomy and Function

The function of the paranasal sinuses is not clear, but theories include humidification and warming of inspired air, lightening of the skull, improvement of vocal resonance, absorption of shock to the face or skull, and secretion of mucus to assist with air filtration. The four paranasal sinuses (maxillary, frontal, ethmoid and sphenoid) develop as outpouchings of the nasal mucosa. They remain connected to the nasal cavity via narrow ostia with a lumen diameter of 1 to 3 mm (Figure 1). The sinuses are lined with mucoperiosteum, which is thinner and less richly supplied with blood vessels and glands than the mucosa of the nasal cavity. Cilia sweep mucus toward the ostia. The ostia of the frontal, maxillary and anterior ethmoid sinuses open into the osteomeatal complex, which lies in the middle meatus lateral to the middle turbinate. The posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses open into the superior meatus and sphenoethmoid recess. The osteo-meatal complex is important because the frontal, ethmoid and maxillary sinuses drain through this area.

Pathophysiology

Failure of normal mucus transport and decreased sinus ventilation are the major factors contributing to the development of sinusitis. Obstruction of the sinus ostia occurs with mucosal edema or any anatomic abnormality that interferes with drainage. Bacterial and viral infections also impair the mucus transport system. The frequency of ciliary beats (normally 700 per minute) decreases to less than 300 per minute during periods of infection. Inflammation causes 30 percent of the ciliated columnar cells to undergo metaplastic changes to mucus-secreting goblet cells. The obstruction and decreased transport results in stagnation of secretions, decreased pH and lowered oxygen tension within the sinus, creating an excellent culture medium for bacteria.

A number of factors can contribute to the development of sinusitis (Table 1). The most common cause of acute bacterial sinusitis is a viral upper respiratory infection. Up to 0.5 percent of upper respiratory infections in adults develop into documented sinusitis.3,4 Children experience six to eight colds per year, and approximately 5 to 10 percent of these infections are complicated by sinusitis.5 Allergic rhinitis has also been considered a contributing factor to sinusitis; however, no causal relationship has been proved, and it is now believed to be a rare initiating factor.6 Iatrogenic factors include mechanical ventilation, nasogastric tubes, nasal packing and dental procedures. Pregnancy, hormone changes associated with puberty, and senile rhinorrhea may be contributing factors. Anatomic variations include tonsillar and adenoid hypertrophy, deviated septum, nasal polyps and cleft palate.

| Allergic rhinitis |

| Anatomic variations |

| Barotrauma |

| Dental infections and procedures, trauma |

| Hormone factors |

| Immunodeficiency disease |

| Inhalation of irritants |

| Mechanical ventilation |

| Nasal dryness |

| Nasotracheal and nasogastric tubes |

| Upper respiratory infections |

Microbiology

Studies have shown that 70 percent of cases of community-acquired acute sinusitis in adults and children are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae.5,7 Branhamella (Moraxella) catarrhalis causes 25 percent of pediatric acute sinus infections. Other pathogens less frequently documented include other streptococcal species (8 percent of adult cases), Staphylococcus aureus (6 percent of adult cases), Neisseria species, anaerobes and gram-negative rods. Viruses are identified in fewer than 10 percent of childhood sinus infections. Infections with beta-lactamase–producing H. influenzae or B. catarrhalis are unusual in adults who have not recently undergone treatment with an antibiotic.8 Nasal cultures are of limited value because the mixed flora does not correlate with bacteria aspirated directly from the sinuses.9 Nasal swabs of 30 percent of the asymptomatic population grow S. aureus, which rarely causes acute sinusitis.10

Fungi are normal flora of the upper airway, but they can cause acute sinusitis in immunocompromised and diabetic patients. Aspergillus species are the most common causes of noninvasive fungal sinusitis.

Diagnosis

One half to two thirds of patients with sinus symptoms who visit primary care physicians are unlikely to have bacterial sinusitis.11,12 Certain diagnostic tools may be useful to the family physician to differentiate a common cold from bacterial sinusitis. Determination of the organism causing acute sinusitis requires puncture, aspiration and culture, but that procedure is rarely appropriate in the family physician's office. Another tool is four-view sinus radiographic studies.9,13–15 Also gaining popularity is endoscopic evaluation of the nasopharynx to identify anatomic abnormalities, determine the presence of purulence around the osteo-meatal complex, and evaluate swelling and inflammation. However, most clinicians now agree that the most appropriate diagnostic approach is a good history and a thorough physical examination.16–18

Studies performed in primary care settings indicate that no single symptom or sign is both sensitive and specific for diagnosing acute sinusitis. Predictive power is improved by combining signs and symptoms into a clinical impression. The accuracy rate of clinical impression ranges from 55 to 75 percent, compared with punctures and radiographs.11,16–18 Among the signs and symptoms used to increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis of acute sinusitis are “double sickening” (biphasic illness), pain with unilateral prominence, purulent rhinorrhea by history, purulent secretions in the nasal cavity on examination, a lack of response to decongestant or antihistamine therapy, facial pain above or below both eyes on leaning forward, and maxillary toothache. The term “double sickening” refers to patients who start with a cold and begin to improve, only to have the congestion and discomfort return (Table 2).

| “Double sickening” |

| Unilateral pain |

| Pain above or below the eyes on leaning forward |

| Maxillary toothache |

| Purulent rhinorrhea by history |

| Purulent secretions in the nasal cavity on examination |

| Poor response to decongestants or antihistamines |

In cases of acute inflammation, palpation and percussion of the involved sinus may elicit tenderness. The following areas should be palpated: the maxillary floor, palpated from the palate; the anterior maxillary wall, from the cheek; the lateral ethmoid wall, from the medial canthus; the frontal floor, from the roof of the orbit; and the anterior frontal wall, from the supraorbital skull.

Transillumination is commonly used to assess the maxillary and frontal sinuses, although poor reproducibility between observers and a lack of correlation with maxillary sinusitis limits the usefulness of transillumination as a diagnostic tool.19

The differential diagnosis of acute sinusitis includes protracted upper respiratory infection, dental disease, nasal foreign body, migraine or cluster headache, temporal arteritis, tension headache and temporomandibular disorders.

Imaging

Imaging studies are not cost effective in the initial assessment and treatment of patients with clinical findings suggestive of acute sinusitis. Radiographs, however, may be helpful in uncertain or recurrent cases. A normal sinus x-ray series has a negative predictive value of 90 to 100 percent, particularly for the frontal and maxillary sinuses. The positive predictive value of x-rays using opacification and air-fluid levels as end points is 80 to 100 percent, but the sensitivity is low since only 60 percent of patients with acute sinusitis have opacification or air-fluid levels.21

The traditional standard study has been a four-view sinus series that includes: (1) the Waters view, in which the occiput is tipped down (patient's chin and tip of the nose are against the film surface) to facilitate viewing of the maxillary and frontal sinuses; (2) the Caldwell view, in which the forehead and tip of the nose are placed in contact with the film (this offers superior visualization of the frontal and ethmoid sinuses); (3) the lateral view, in which the sphenoid sinus and the posterior frontal sinus wall are visualized; and (4) the submentovertex view, in which the sphenoid sinuses and posterior ethmoid cells are visualized.

A Veterans Affairs general medicine clinic study,22 using the standard criteria of air-fluid level, sinus opacity or mucosal thickening (greater than 6 mm) to diagnose sinusitis, demonstrated that a single Waters view had a high level of agreement with the complete sinus series. In this study, 88 percent of patients with sinusitis had maxillary disease. A single occipitomental (Waters) view in children has an overall accuracy of 87 percent in diagnosing acute sinusitis.23 In those few situations where x-rays are indicated, utilizing a single Waters view is preferred over the traditional four-view study.

Computed tomographic (CT) scanning of the sinuses has no place in the routine evaluation of acute sinusitis. Limited sinus CT studies are useful in delineating the osteomeatal complex in anticipation of an otolaryngology consultation and functional endoscopic sinus surgery to evaluate and treat chronic sinus inflammation. Sinus CT scanning has a high sensitivity but a low specificity for demonstrating acute sinusitis.24,25 Forty percent of asymptomatic patients and 87 percent of patients with community-acquired colds have sinus abnormalities on sinus CT.26

Therapy

Adjunctive Treatment

In addition to considering antibiotic therapy in patients who present with acute sinusitis, family physicians may make recommendations regarding adjunctive therapies such as diet, steam, saline nasal rinses, topical decongestants, oral decongestants, mucolytic agents, antihistamines and intranasal corticosteroids. These adjunctive therapies are designed to promote ciliary function and decrease edema to improve drainage through the sinus ostia. Unfortunately, few randomized controlled trials have investigated the effectiveness of these approaches.27,28

Sipping hot fluids, applying moist heat with a hot towel and inhaling steam may improve ciliary function and decrease congestion and facial pain. Salt water nasal rinses provide short-term relief of congestion by removing crusts and secretions. A normal saline solution can be made by adding one-fourth teaspoon of table salt to 8 oz of warm water to be delivered with a squeeze bottle or pump spray bottle.

Decongestants may provide temporary relief of nasal congestion. Nasal spray or drops act by constricting the sinusoids in the nasal mucosa (Table 3). These sinusoids are regulated by both alpha1 and alpha2 adrenoreceptors.29 The nasal mucosal blood flow is not significantly affected by the alpha1 agonists, but recent studies suggest that oxymetazoline (Afrin), a selective alpha2 adrenoreceptor agonist, interferes with the healing of maxillary sinusitis by decreasing nasal mucosal blood flow.30 As a result, alpha1 agonists, such as phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine), are the preferred topical mucosal decongestants. Because of the risk of rebound rhinitis (rhinitis medicamentosa), the use of topical decongestants should be restricted to three to four days or less.

| Vasoconstrictors* | Adrenoceptor activity | Onset (minutes) | Duration of action (hours) | Dosage† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topical agents | |||||

| Sympathomimetic amines | |||||

| Phenylephrine (Neo-Synephrine) | Alpha1 | 1 to 3 | 1 to 4 | 2 to 3 sprays in each nostril every 3 to 4 hours | |

| Imidazoline derivatives | |||||

| Naphazoline (Naphcon Forte) | Alpha2 | 1 to 3 | 2 to 6 | 1 to 2 sprays in each nostril no no more than every six hours | |

| Oxymetazoline (Afrin 12-Hour) | Alpha2 | 1 to 3 | 5 to 12 | 2 to 3 sprays twice daily | |

| Xylometazoline (Otrivin) | Alpha2 | 1 to 3 | 6 to 12 | 2 to 3 drops or 2 to 3 sprays every 8 to 10 hours | |

| Systemic agents | |||||

| Phenylpropanolamine (Tavist-D [timed release]) | Alpha1 and alpha2, beta1 and beta2 | 15 to 30 | 8 to 12 | 1 tablet every 12 hours | |

| Pseudoephedrine (Sudafed) | Alpha1 and alpha2, | 15 to 30 | 4 to 8 | 60 mg every 4 to 6 hours | |

| (Novafed [timed release]) | Beta1 and beta2 | 8 to 12 | 120 mg every 12 hours | ||

Oral decongestants such as pseudoephedrine (Novafed), taken in a dosage of 60 to 120 mg, will reduce nasal congestion within 30 minutes, and the effect persists for up to four hours. Side effects include nervousness, insomnia, tachycardia and hypertension. No clinical trials demonstrate the effectiveness of oral decongestants in treating acute sinusitis.

The mucolytic agent guaifenesin, which is usually given in decongestant combinations (e.g., Entex L.A.) is widely prescribed to thin secretions despite its lack of demonstrated effectiveness. The recommended dosage of 2,400 mg is just below the level that may cause emesis. A recent study comparing the effects of guaifenesin and placebo on nasal mucociliary clearance and ciliary beat frequency failed to show any measurable effect.31

There is no rationale for using antihistamines in treating acute sinusitis, since histamine does not play a role in this condition and these agents dry the mucous membranes with crusts that block the osteo-meatal complex. The newer, nonsedating, second-generation antihistamines do not cause excessive dryness and crusting; however, no evidence supports the use of these expensive agents.

Although widely prescribed for acute sinusitis, intranasal steroids are of questionable benefit. Given the limited role of allergic rhinitis in the etiology of acute sinusitis and the limited effectiveness of steroid agents in clinical trials, topical steroids should not routinely be used in the management of acute sinusitis.

Antibiotics

The appropriate role of antibiotics in the treatment of acute sinusitis is not clear. A recent study32 of adult patients with acute maxillary sinusitis diagnosed by using clinical and radiographic examinations and treated with amoxicillin (in a dosage of 250 mg three times daily for seven days) or placebo showed no significant difference in outcomes. After two weeks, 83 percent of the amoxicillin group and 77 percent of the placebo group had greatly reduced symptoms, and 65 percent and 53 percent, respectively, were cured. In contrast, other randomized controlled trials33,34 have demonstrated the effectiveness of antibiotic treatment of acute sinus infections in adults and children. A study34 in a Norwegian general practice compared amoxicillin, penicillin and placebo in the treatment of adult patients with acute sinusitis. Eighty-six percent of the antibiotic group considered themselves cured or much better, compared with 57 percent of the placebo group. The median duration of sinusitis in the amoxicillin, penicillin and placebo groups was nine, 11 and 17 days, respectively. In a study of children two to 16 years of age with acute maxillary sinusitis, the overall cure rate on day 10 was 67 percent for amoxicillin, 64 percent for amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (Augmentin) and 43 percent for placebo.33 Acute sinusitis is caused by the same organisms that cause otitis media, and drug choices are similar.

Although the incidence of beta-lactamase–producing organisms causing maxillary sinusitis is 25 percent in some communities, there has been no superior outcome with the use of broad-spectrum antibiotics compared with amoxicillin. A number of studies evaluating antibiotic treatment of sinusitis have shown that amoxicillin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim), penicillin V (V-Cillin K), minocycline (Minocin), doxycycline (Vibramycin), cefaclor (Ceclor), azithromycin (Zithromax), amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium, loracarbef (Lorabid), bacampicillin (Spectrobid), cefuroxime (Ceftin) and clarithromycin (Biaxin) are similarly effective in producing symptomatic and bacteriologic improvement in 80 to 90 percent of patients.35–43 Most of the studies used seven to 14 days of antibiotic therapy.

A recently reported study44 of adult male patients in a general medicine Veterans Affairs clinic with sinus symptoms and radiographic evidence of maxillary sinusitis compared the effectiveness of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole twice daily for three days and 10 days. By 14 days, 77 percent of the three-day group and 76 percent of the 10-day treatment group rated their symptoms as cured or much improved, suggesting that shorter courses of therapy than the traditional 10- to 14-day course may be effective. However, some have argued against the validity of this study, so standard therapy is preferred until further data are available.

Most patients (90 percent) with a diagnosis of acute sinusitis expect to receive a prescription for antibiotics, along with adjunctive treatment recommendations.45 Treatment considerations include patient expectations, the natural course of untreated disease, time lost from work, documented effectiveness, adverse effects, and duration and cost of therapy. Use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, nasal corticosteroids and antihistamines adds to the expense of treatment with little additional benefit. More controlled trials are needed to clarify the effectiveness of these various treatment options (Table 4).

| Antibiotic | Usual adult dosage* | Cost† |

|---|---|---|

| First-line therapy | ||

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, double-strength (Bactrim DS) | 160/800 mg twice daily | $ 25.00; generic: 8.00 |

| Amoxicillin | 500 mg three times daily | 12.00; generic: 10.00 to 14.00 |

| Second-line therapy | ||

| Amoxicillin-clavulanate potassium (Augmentin) | 500/125 mg three times daily | 94.00 |

| Cefaclor (Ceclor) | 500 mg three times daily | 128.00; generic: 115.00 to 117.00 |

| Cefuroxime (Ceftin) | 500 mg twice daily | 132.00 |

| Cefixime (Suprax) | 400 mg twice daily | 135.00 |

| Clarithromycin (Biaxin) | 500 mg twice daily | 65.00 |

| Doxycycline (Vibramycin) | 200 mg on day 1, then 100 mg on days 2 through 10 | 21.00; generic: 2.00 to 6.00 |

Treatment Failure and Complications

Despite the use of antibiotics and selected adjunctive therapy, 10 to 25 percent of primary care patients continue to have symptoms. The office re-evaluation of these patients, two to three weeks after the first visit, should include a careful history and physical examination, and a single Waters view of the sinuses should be taken to confirm the diagnosis. Empiric therapy may include a two-week course of a second-line antibiotic (Table 4).

Antibiotics appear to be of little benefit in the treatment of chronic sinusitis. Recurrent or chronic sinusitis often requires otolaryngology consultation. CT imaging of the osteomeatal complex followed by functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) often successfully restores the physiology of sinus aeration and drainage. Between 80 and 90 percent of FESS patients experience significant improvement of symptoms.21

In the era of antibiotic therapy and adequate access to primary care, major complications of sinusitis are rare. However, 75 percent of all orbital infections are the direct result of sinusitis.46