Am Fam Physician. 2002;65(11):2299-2307

Patients commonly present to family physicians with low back pain. Because the majority of patients fully or partially recover within six weeks, imaging studies are generally not recommended in the first month of acute low back pain. Exceptions include patients with suspected cauda equina syndrome, infection, tumor, fracture, or progressive neurologic deficit. Patients who do not improve within one month should obtain magnetic resonance imaging if a herniated disc is suspected. Computed tomographic scanning is useful in demonstrating osseous structures and their relations to the neural canal, and for assessment of fractures. Bone scans can be used to determine the extent of metastatic disease throughout the skeletal system. All imaging results should be correlated with the patient’s signs and symptoms because of the high rate of positive imaging findings in asymptomatic persons.

Family physicians frequently encounter patients with low back pain. In the United States, at least 80 percent of adults have at least one episode of low back pain during their lifetimes.1,2 Low back pain and degenerative joint disease account for 4.9 percent of all adult physician visits, and the direct medical costs related to low back pain exceed $25 billion annually.3,4 Fortunately, in as many as 90 percent of patients, acute low back pain resolves within six weeks regardless of treatment methods.2,5 More than 50 percent of patients with sciatica or mild neurologic deficits also recover, with only 5 to 10 percent of cases requiring surgery.5,6 Despite the frequency with which this condition is presented to physicians, there is a wide range in the use of imaging tests. The following discussion reviews specific imaging modalities as applied to the diagnosis of low back pain.

‘Red Flags’ Requiring Diagnostic Imaging

In a study7 of the use of imaging tests in the evaluation of low back pain among internists and family physicians, the average use rates were 16 percent for radiography, 5 percent for computed tomography (CT), and 1 percent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). More importantly, there were wide ranges among physicians: 2 to 48 percent for radiography; zero to 30 percent for CT, and zero to 9 percent for MRI.7

Because funds for medical testing are limited, physicians must fully understand the attributes and limitations of the various imaging modalities used for the evaluation of low back pain. Figures 18 and 2 are decision algorithms to guide the physician in the judicious use of imaging as a diagnostic tool for resolving low back pain.

| Possible condition | Findings from medical history |

|---|---|

| Fracture | Major trauma (motor vehicle accident, fall from height) |

| Minor trauma or strenuous lifting in an older or osteoporotic patient | |

| Tumor or infection | Age >50 years or <20 years |

| History of cancer | |

| Constitutional symptoms (fever, chills, unexplained weight loss) | |

| Recent bacterial infection | |

| Intravenous drug use | |

| Immunosuppression (corticosteroid use, transplant recipient, HIV infection) | |

| Pain worse at night or in the supine position | |

| Cauda equina syndrome | Saddle anesthesia |

| Recent onset of bladder dysfunction Severe or progressive neurologic deficit in lower extremity |

Patients who have experienced recent trauma should be considered for radiographic evaluation. Imaging studies are used to evaluate the extent of osseous, ligamentous, neural, and soft tissue injuries. The initial imaging study should be cost-effective and expeditious, and maintain a minimal diagnostic error rate. For these reasons, a radiographic series may be the most appropriate screening examination.

Patients with infection or tumor should be initially screened with plain radiographs followed by MRI. These patients are generally on either end of the age spectrum, and physical examination may reveal unexplained weight change, fever, chills, night sweats, or a history of cancer.

Immediate imaging is also necessary if the patient has—or is suspected of having—cauda equina syndrome. This condition is most common in persons between 30 and 40 years of age following an acute disc herniation. Physical examination reveals low back pain with bilateral weakness of the lower extremity, saddle anesthesia, and bowel and bladder incontinence. These patients should undergo immediate MRI and be sent for surgical consultation.

The initial radiographic series should be followed with MRI and/or CT if results of the screening examination or the physical examination are abnormal. In cases of neurologic deficit, CT and/or MRI scans should be obtained to depict the spinal cord and surrounding tissue. The superiority of CT in capturing details of osseous structures allows for thorough assessment of fractures. In cases where the initial radiographic series detects misalignment of the spine, the imaging course is determined by the degree of subluxation. If it can be safely obtained, a flexion-extension film allows for assessment of ligamentous injury. The majority of patients with low back pain do not belong to any of these three groups.

Patients who have clinically improved can be managed conservatively with a program consisting of rest, exercise, and medication. If the patient continues to be symptomatic after six weeks of conservative care, plain films should be obtained to identify any mechanical etiology for their pain. If radiculopathy is present and a herniated disc is suspected, MRI should be obtained if the patient fails to improve clinically.

In the evaluation of patients with low back pain, it is essential to correlate all image findings with the patient’s signs and symptoms on physical examination. A diagnosis should not be based solely on diagnostic imaging without firm correlation to symptoms. A general set of rules cannot be applied to all patients, so physicians must properly evaluate each patient and use the appropriate diagnostic imaging tests judiciously.

Plain Radiography

Traditionally, the plain radiograph has been the first imaging test performed in the evaluation of low back pain because it is relatively inexpensive, widely available, reliable, quick, and portable. Two major drawbacks to radiography are difficulty in interpretation and an unacceptably high rate of false-positive findings.9 Plain radiographs are not required in the first month of symptoms unless the physical examination reveals specific signs of trauma or there is suspicion of tumor or infection.8 It is important to obtain pictures that are free of motion or grid artifacts and that display soft tissue and osseous structures of the entire lumbar spine.

Having a standard approach to evaluating radiographs can help prevent a missed diagnosis; it is crucial to develop and maintain a specific sequence of observation. The traditional sequence includes anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the lumbar spine, primarily to detect tumors or spinal misalignments such as scoliosis. In the AP view, indicators of a normal spine include vertical alignment of the spinous processes, smooth undulating borders created by lateral masses, and uniformity among the disc spaces.

Misalignment of the spinous processes suggests a rotational injury such as unilateral facet dislocation. The AP view of the lumbar spine should include the whole pelvis; this allows for evaluation of the acetabulum and femoral heads and for the detection of possible degenerative changes to the pelvis.

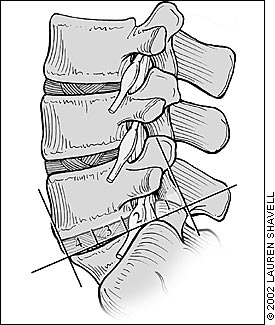

The lateral view (Figure 3) provides a good image of the vertebral bodies, facet joints, lordotic curves, disc space height, and intervertebral foramen. Decreased disc space height can be indicative of disc degeneration, infection, and postsurgical condition. Unfortunately, there is poor correlation between decreased disc height and the etiology of low back pain.

Anterior slippage (spondylolisthesis) of the fifth lumbar vertebra on the sacral base can be identified in lateral views. This slippage is measured by dividing the sacral base into four equal divisions. The position of the posterior-inferior corner of the fifth lumbar vertebra is then made relative to these divisions (Figure 4). The degree of spondylolisthesis is categorized as grade 1 through grade 4, based on that position (Figure 5). If the lumbar vertebra is completely anterior to the sacral base, spondylolisthesis has occurred.

Oblique views with the radiograph tube angled at 45 degrees improve visualization of the neural foramina and pars interarticularis and are used to confirm suspicions generated from the initial imaging assessment. Oblique views are used to show tumors, facet hypertrophy, and spondylosis or spondylolisthesis.

Flexion-extension views are helpful in assessing ligamentous and bony injury in the axial plane. Use of these views should be limited to patients who do not have other radiographic abnormalities and patientes who are neurologically intact, cooperative, and capable of describing pain or early onset of neurologic symptoms. Flexion-extension views can be used in trauma patients, especially those with muscle spasm, which may be the only sign of spinal instability.

When examining the lumbar spine for possible fracture, it is important to include the lower portion of the thoracic spine because of the high occurrence of injury between levels T12 and L2. This region is more prone to injury because of the change in orientation of the facet joints between the thoracic spine and the lumbar spine and because it lies directly beneath the more rigid thoracic spine, which is stabilized by the rib cage.

Degenerative changes are often evident on plain radiographs; however, caution must be used in making a diagnosis based on degenerative radiographic changes because of the high rate of asymptomatic degenerative changes. Radiographic evidence of degenerative change is most common in patients older than 40 years and is present in more than 70 percent of patients older than 70 years.9 Degenerative changes have been reported to be equally present in asymptomatic and symptomatic persons.9 The incidence of intervertebral narrowing and irregular ossification of the vertebral end plates has also been shown to be associated with increased age.10 Even though plain radiographs usually provide little definitive information, they should be included in the screening examination for patients with certain red flags (Table 1).8

Myelography

Myelography uses a contrast solution in conjunction with plain radiography to improve visualization of the spinal cord and intrathecal nerve roots. Water-soluble contrast agents (iohexol and iopamidol) are injected into the subarachnoid space. After injection, AP, lateral, and oblique views are obtained.

Myelography can be helpful in detecting a herniated disc above or below a segment that may be ambiguous or distorted on MRI secondary to metal placement. It is also useful in patients who are claustrophobic or have a pacemaker, or for whom MRI is otherwise contraindicated. A CT scan performed within two hours of completing myelography enhances the diagnostic quality and reliability of the imaging study by more accurately depicting osteophytes, disc herniations, and spinal cord contour.11

The most important limitation of myelography is its inability to visualize entrapment of the nerve root lateral to the termination of the nerve root sheath. It is thus unable to detect any far lateral disc herniations, which reportedly account for 1 to 12 percent of all lumbar disc herniations and occur most often at the L4-L5 and L3-L4 levels.14,15

Possible side effects of myelography include dural tear, which can cause headaches, nausea, vomiting, pain or tightness in the back or neck, dizziness, diplopia, photophobia, tinnitus, or blurred vision.16,17 It is thought that a dural tear can result in a loss of cerebrospinal fluid volume, decreasing the brain’s supporting cushion, so that when the patient is standing there is tension on the brain’s anchoring structures.18 A persistent postmyelography headache can be treated with an epidural blood patch, in which 10 to 20 mL of autologous blood is injected into the epidural space under sterile conditions.19

Computed Tomography

CT is used to complement information obtained from other diagnostic imaging studies such as radiography, myelography, and MRI. The principal value of CT is its ability to demonstrate the osseous structures of the lumbar spine and their relationship to the neural canal in an axial plane. A CT scan is helpful in diagnosing tumors, fractures, and partial or complete dislocations. In showing the relative position of one bony structure to another, CT scans are also helpful in diagnosing spondylolisthesis. They are not as useful as MRI in visualizing conditions of soft tissue structure, such as disc infection. The data used to generate the axial images are obtained in contiguous, overlapping slices of the target area. The axial image data can be reformatted to construct views of the scanned area in any desired plane.

The limitations of CT include less-detailed images and the possibility of obscuring nondisplaced fractures or simulating false ones. In addition, radiation exposure limits the amount of lumbar spine that can be scanned, and results are adversely affected by patient motion; spiral CT addresses these weaknesses because it is more accurate and faster, which decreases a patient’s exposure to radiation exposure.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

MRI has emerged as the procedure of choice for diagnostic imaging of neurologic structures related to low back pain (Figure 6). Although a significant variation can exist in the quality of lumbar spine MRI images as a function of the imaging center and the image interpreter,20 MRI is better than CT in showing the relationship of the disc to the nerve, and at locating soft tissue and nonbony structures. For this reason, it is better than CT at detecting early osteomyelitis, discitis, and epidural-type infections or hematomas.

MRI provides high resolution, multiaxial, multiplanar images of tissue with no known biohazard effects. The only contraindication to MRI is the presence of ferromagnetic implants, cardiac pacemakers, intracranial clips, or claustrophobia. Two different types of images are generally obtained using MRI: T1-weighted images in the sagittal plane and T2-weighted images in the axial and sagittal planes.

Spin echo is the standard pulse sequence when using T1-weighted images, which are commonly used to contrast tissues such as neural foramina and nerve roots. Spin echo provides good spatial resolution, allowing for confirmation of disc herniation, although the size of the herniation is difficult to determine. It can also detect metastatic disease by surveying the marrow signal intensity or by showing loss of fat.

T2-weighted spin echo images enhance the signal of the cerebrospinal fluid, making this series more sensitive to spinal pathology (such as tumor, infection, osteomyelitis, and discitis), but it is often more time consuming with the pulse sequence.

As with other imaging techniques, MRI can identify abnormalities in asymptomatic persons. In one study,21 MRIs of 67 asymptomatic persons 20 to 80 years of age were obtained. At least one herniated disc was identified in 20 percent of persons younger than 60 years and in 36 percent of persons older than 60 years.21 Another study22 discovered that 63 percent of asymptomatic persons had disc protrusion, and 13 percent had disc extrusion.

Many imaging centers use contrast-enhanced MRI to increase the visualization of herniated discs. Recent studies23 have concluded that contrast enhancement in patients with previous lumbar spine surgery added limited diagnostic value and often resulted in more inaccurate interpretations. Gadolinium is thought to enhance the appearance of nerve roots in viral or inflammatory conditions and can help distinguish recurrent disc herniation from scar tissue in the postoperative spine.24

Nuclear Medicine

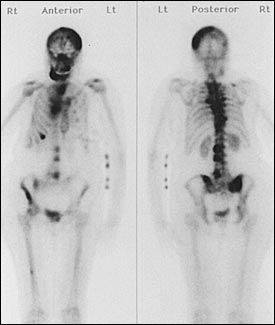

Plain radiographs, CT scans and MRIs reveal morphologic changes in bone. Bone scintigraphy, the most common form of nuclear medicine, detects biochemical changes through images that are produced by scanning and mapping the presence of radiographic compounds (usually technetium Tc 99m phosphate or gallium 67 citrate). These compounds are incorporated into hydroxyapatite crystals that are deposited in an osteoid matrix during new bone formation. The image produced indicates bone turnover, a common occurrence in bone metastases, primary spine tumors, fracture, infarction, infection, and other metabolic bone diseases.

Bone metastases normally appear as multiple foci of increased tracer uptake asymmetrically distributed (Figure 7). In extreme cases of bone metastases, diffusely increased uptake of tracer results in every bone being uniformly illustrated and can be falsely interpreted as negative. Aggressive tumors that do not invoke an osteoblastic response, such as myeloma, can also yield a negative examination.

Primary spine tumors are usually benign. Osteoid osteoma, osteoblastoma, aneurysmal bone cyst, and osteochondroma produce an active bone scan. These tumors generally affect the posterior elements of the spine. CT must be used to differentiate them and isolate their anatomic position.

Recent studies25,26 have evaluated the ability of bone scans, with the addition of single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), to distinguish benign lesions from malignant lesions. SPECT scan differs from bone scan because it provides a three-dimensional image that enables physicians to locate the lesion more precisely. Lesions that affect the pedicles are a strong indicator of malignancy, while lesions of the facets are likely to be benign. Lesions of the vertebral body or spinous process are just as likely to be benign as malignant and, therefore, offer little diagnostic evidence.25

Gallium 67 is the most effective radioactive tracer in assessing infectious spondylitis. One study27 compared bone scans using gallium 67 and Tc 99m with radiography and MRI. Gallium 67 had a sensitivity of 92 percent, a specificity of 100 percent, and an accuracy of 95 percent.27 MRI was the second-best method of evaluation for infection, with a sensitivity of 96 percent, a specificity of 93 percent, and an accuracy of 94 percent.27

Discography

Discography is used in conjunction with CT or MRI to localize disc herniation or fissure in the annulus fibrosis. A volume of contrast media is injected into the disc space to determine the integrity of the intervertebral disc. In the normal disc, the annulus fibrosis solidly encloses the nucleus pulposus and is only capable of accepting 1 to 1.5 mL of contrast media. If 2 mL or more of contrast media can be injected, there is likely to be a degenerative change in the disc.

In addition to determining the available volume of the disc, discography is used to reproduce the symptoms associated with a possible herniated disc. The patient’s response to pain can help confirm the source of the symptoms. When saline or dye is injected, it pressurizes the disc, and the patient is able to confirm that this pain is the same as the pain he or she has been having.

Discography should be used cautiously because of the possibility of false-positive results. In one study,28 lumbar discography was performed on 26 volunteers who were pain-free or had chronic cervical pain or primary somatization disorders without low back pain. Significant positive pain responses were reported in 10 percent of the pain free group, 40 percent of the chronic cervical pain group, and 83 percent of the primary somatization disorder group.28 Based on these results,28 the findings from discography should be interpreted cautiously. Discography is an invasive test that has an inherent risk of infection and neural injury. It should be used only to confirm an initial diagnosis, not as the primary diagnostic tool.