Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(4):875-881

Occult gastrointestinal bleeding usually is discovered when fecal occult blood test results are positive or iron deficiency anemia is detected. Fecal occult blood testing methods vary, but all have limited sensitivity and specificity. The initial work-up for occult bleeding typically involves colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy, or both. In patients without symptoms indicating an upper gastrointestinal tract source or in patients older than 50 years, colonoscopy usually is performed first. About one half of patients with gastrointestinal bleeding do not have an obvious source of the bleeding. In those patients, small bowel imaging or repeat panendoscopy may be performed. Barium studies of the small bowel are widely available but have limited diagnostic utility. Mucosal lesions such as vascular ectasias, a common cause of obscure bleeding, may be missed by small bowel studies. Small bowel endoscopy is difficult to perform but has a higher diagnostic yield. Capsule endoscopy is a newer technique that allows noninvasive small bowel imaging. Radionuclide red blood cell scans or angiography may be useful in patients with active bleeding. Treatment of bleeding most often involves endoscopic ablation of the bleeding site with thermal energy, if the site is accessible. Angiographic embolization may be used to treat lesions that cannot be reached endoscopically. Diffuse vascular lesions, which are not uncommon, are difficult to treat. Medical treatment, usually with combined hormone therapy, has limited utility. Surgical treatment of obscure bleeding often fails or is not feasible because of multiple bleeding sites.

Occult bleeding (i.e., gastrointestinal bleeding that is not visible to the patient or physician) typically is discovered when giron deficiency anemia is detected or the result of a fecal occult blood test (FOBT) is positive.1 Obscure bleeding is gastrointestinal bleeding from an unknown source that persists or recurs after a negative initial evaluation (e.g., colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy [EGD]).1 Obscure bleeding may be occult (i.e., not visible) or overt (i.e., continued passage of visible blood).

Fecal Occult Blood Testing

It is normal to lose 0.5 to 1.5 mL of blood daily in the gastrointestinal tract,3 and melena usually is identified when more than 150 mL of blood are lost in the upper gastrointestinal tract.3 FOBTs have sufficient sensitivity to detect bleeding that is not visible in the stool. There are three classes of FOBTs: guaiac-based tests, hemeporphyrin tests, and immunochemical tests.

In guaiac-based tests, the pseudoperoxidase activity of hemoglobin turns the guaiac compound blue in the presence of hydrogen peroxide.3,4 If certain substances are in the stool (Table 2),3 the results may be false positive. Patients usually are warned not to eat red meat or certain fruits and vegetables for 72 hours before testing. Use of aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) should be avoided for one week before testing. False-negative results may occur in patients taking vitamin C; patients should be advised not to take vitamin C in the week before testing. Patients are encouraged to eat foods high in fiber for one week before testing to cause more rapid stool transit. Hemoccult II and Hemoccult II SENSA are the most commonly used guaiac-based tests.3 Widely available and inexpensive, they can be performed rapidly in the physician's office or by the patient at home. Hemoccult II SENSA has higher sensitivity3; rehydration of stool cards before testing increases sensitivity but lowers specificity.

| Upper tract source | ||

| Esophagus/stomach | ||

| Reflux esophagitis* | ||

| Erosive gastritis/ulceration* | ||

| Varices | ||

| Cameron's erosions within a hiatal hernia | ||

| Dieulafoy's lesion (i.e., dilated aberrant vessel underlying a small mucosal defect) | ||

| Gastric antral vascular ectasia (i.e., “watermelon stomach”) | ||

| Portal gastropathy | ||

| Small intestine | ||

| Duodenitis | ||

| Celiac sprue | ||

| Meckel's diverticulum | ||

| Crohn's disease (can occur anywhere but commonly involves terminal ileum) | ||

| Lower tract source | ||

| Colon | ||

| Diverticula (usually causes overt bleeding) | ||

| Ischemic colitis | ||

| Ulcerative colitis | ||

| Other colitis | ||

| Infection (e.g., hookworm, whipworm, Strongyloides, ascariasis, tuberculous enterocolitis, amebiasis, cytomegalovirus) | ||

| Rectum | ||

| Fissure | ||

| Hemorrhoids | ||

| Any gastrointestinal source | ||

| Vascular ectasia/angiodysplasia | ||

| Carcinoma (especially colon)* | ||

| Vasculitis | ||

| Aortoenteric fistula | ||

| Other cancers (e.g., Kaposi's sarcoma, lymphoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoa, carcinoid tumors, melanoma) | ||

| Large polyps | ||

| Telangiectasia (i.e., Osler-Weber-Rendu syndrome) | ||

| Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome | ||

| Amyloidosis | ||

| Hemangioma | ||

| Radiation-induced mucosal injury | ||

| Extraintestinal source | ||

| Hemobilia | ||

| Hemosuccus pancreaticus | ||

| Hemoptysis | ||

| Nasopharyngeal (e.g., epistaxis, bleeding gums) | ||

| Factitious | ||

| Long-distance running | ||

| No source found | ||

The heme-porphyrin test, HemoQuant, measures hemoglobin-derived porphyrins, allowing quantitative measurement of hemoglobin in stool.3 Its use is limited because it has a higher rate of false-positive results, is expensive, and requires laboratory time. Unlike the guaiac-based tests, dietary peroxidases do not cause false-positive results with the hemeporphyrin test.

Immunochemical FOBTs, such as HemeSelect and FECA-EIA, detect intact human hemoglobin. These tests are more specific for bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract, and consumption of red meat or dietary peroxidases does not produce false-positive results. Disadvantages include limited availability and the time required to process the test. Immunochemical FOBTs do not detect digested hemoglobin, so they are not able to detect bleeding from upper gastrointestinal sources.3

Because of the possibility of bleeding from trauma, it is not known if a positive result on a test performed on a sample from a digital rectal examination differs from a positive test of spontaneously evacuated stool. Ideally, for routine screening, stool cards should be made with spontaneously evacuated stool, and the patient should follow the recommended pretesting dietary restrictions. Daily use of warfarin (Coumadin) or low-dosage aspirin (i.e., 81 mg per day) does not raise fecal blood levels enough to cause positive guaiac-based FOBT results.5

Work-up of Occult Bleeding

ENDOSCOPY

Initial evaluation of occult bleeding typically consists of colonoscopy or EGD. In patients older than 50 years, colonoscopy usually reveals the source of bleeding; it should be the first test performed.3 A tumor, a polyp larger than 1 cm, colitis, or vascular ectasia on colonoscopy can account for a lower gastrointestinal source for heme-positive stool. Initial evaluation with EGD may be necessary in patients with risk factors such as NSAID or aspirin use (at higher dosages) or upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Some additional findings that may suggest a bleeding source are given in Table 3.6,7

| Extraintestinal blood loss |

| Epistaxis |

| Gingival bleeding |

| Tonsillitis/pharyngitis |

| Hemoptysis |

| Medications causing gastric irritation |

| Aspirin |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Vitamin C |

| Exogenous peroxidase activity |

| Red meat consumption (nonhuman hemoglobin) |

| Fruit consumption (cantaloupe, grapefruit, figs) |

| Uncooked vegetable consumption (radish, cauliflower, broccoli, turnip, horseradish; less likely: cucumber, carrot, cabbage, potato, pumpkin, parsley, zucchini) |

The use of single-column barium enemas has been discontinued because of the unacceptably high rate of missed colon cancers. Double-contrast barium enemas are used primarily when results of a colonoscopy are suboptimal.8

If endoscopic evaluation of upper and lower tracts is negative or equivocal, investigation of a small bowel bleeding source may be necessary, especially in patients with persistent or recurrent bleeding. Because of a substantial false-negative rate for lesions on initial endoscopy, repeat upper and lower endoscopy is recommended by some authorities before small bowel imaging.1 [Evidence level C, consensus/expert guidelines] Cameron's erosions (within a hiatal hernia), peptic ulcer disease, and vascular ectasias are the most common upper tract lesions found on repeat endoscopy, and cancer and angiodysplasias are the most commonly overlooked lower tract abnormalities.1

The distance of the small intestine from the mouth and anus makes small bowel endoscopy difficult. The procedure is limited by intestinal motility and the looping, free-hanging course of the small bowel. Typically, enteroscopy reaches only the proximal small bowel, missing the ileum. Although enteroscopy is not universally available, it allows for intervention if a bleeding site is identified.

Small bowel barium studies are more readily accessible than enteroscopy. However, small bowel follow-through (SBFT) examinations and enteroclysis may not detect mucosal-based lesions such as vascular ectasias, which are a common cause of small bowel bleeding. SBFT is a simple test involving ingestion of contrast dye followed by timed radiographic imaging. Enteroclysis is similar, except the barium is inserted through a tube that passes through the nose into the small intestine. A balloon is inflated to prevent migration of the tube, and a barium methyl cellulose mixture is instilled rapidly. This technique allows for a more continuous image of the small intestines. Although it is less pleasant for the patient, it has higher diagnostic yield and sensitivity than SBFT.8 “Tubeless enteroclysis” is a recently introduced variation that allows oral ingestion of contrast dye, but it has not been widely studied yet.

Intraoperative endoscopy has been used to examine the small bowel when other techniques fail to detect a bleeding source, but surgery itself has attendant increased risk and does not always add to the diagnosis. Surgical manipulation can create artifacts that may be mistaken for bleeding lesions. Intraoperative methods have determined a source of occult bleeding in up to 40 percent of undiagnosed cases,9 but they examine only 50 to 80 percent of the small bowel.10

| Clinical clue | Likely cause of bleeding |

|---|---|

| Age greater than 50 | Carcinoma |

| Chronic renal failure | Vascular ectasia/angiodysplasia |

| Cutaneous hemangiomas | Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome |

| Chronic diarrhea/abdominal pain | Celiac sprue |

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | Kaposi's sarcoma, cytomegalovirus colitis |

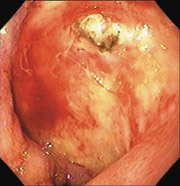

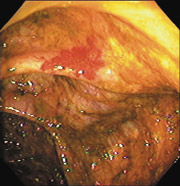

New microtechnology has added to the investigative methods available for small bowel visualization. Capsule endoscopy uses a wireless video capsule that is swallowed by the patient and propelled by peristalsis.11 This device allows patients to go about their normal activities during imaging. The capsule, which is disposable and is not retrieved, is 30 × 11 mm, with a six-hour battery life. A microchip camera and light source photograph and transmit two images per second to a recorder that is worn by the patient. The images are downloaded to a computer and reviewed (Figures 1 and 2).

One randomized trial showed that more lesions were found with capsule endoscopy than with standard enteroscopy.10 Capsule endoscopy can be used in patients who are too frail to undergo standard endoscopy. Complications from capsule endoscopy, such as impaction and small bowel stricture, have been reported.12 Capsule endoscopy is a diagnostic tool that does not allow for intervention. Its clinical usefulness in large bowel imaging has not yet been evaluated.

NUCLEAR MEDICINE SCANS AND ANGIOGRAPHY

Radionucleotide imaging with tagged red blood cells is most useful in the evaluation of active gastrointestinal bleeding. These scans are more likely to localize a bleeding source when the rate of blood loss exceeds 0.1 to 0.4 mL per minute (i.e., when the patient has a need for a tranfusion of more than two units of blood per day).2,3 Pooling of blood in the intestine may result in false localizations, and red blood cell scans have a substantial false-negative rate because intermittent bleeding is often missed during testing.

Direct angiography is more likely to demonstrate an exact location of bleeding if the rate is greater than 0.5 mL per minute, but this technique is more invasive than red blood cell scans.2 Direct angiography may be useful in identifying nonbleeding lesions with a typical vascular pattern, such as that of angiodysplasia or neoplasia. Interventional radiologists also may administer specific embolization therapy if there is an amenable lesion. Neither tagged red blood cell scans nor angiography is useful in patients with obscure bleeding, because the blood loss often is too low to be detected.

Some physicians order provocative tests using anticoagulants, vasodilators, or clotlysing agents to provoke bleeding and increase the likelihood that a bleeding source will be found.8 Because these tests could initiate uncontrolled bleeding, they rarely are used and usually are not recommended. Although red blood cell scans or angiography may be useful in identifying the location of bleeding, these modalities often are unable to determine the specific cause of the bleeding. A Meckel's scan may be useful to rule out a Meckel's diverticulum in young patients with continued small bowel bleeding of uncertain etiology.

| Method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Small bowel follow through/enteroclysis | Minimal side effects or risk | Misses mucosal lesions Enteroclysis tube uncomfortable |

| Tagged red blood cell scan | Good for rapid bleeding | Nonspecific, false localizations, and missed bleeding Cannot determine cause |

| Meckel's scan | Good in young patients to find diverticulum | Specific only for Meckel's diverticulum |

| Angiography | Good for rapid bleeding Can intervene in rapid bleeding if source is located | Invasive; risk of intestinal infarction with embolization Less likely to determine cause than endoscopy Risk of intravenous contrast reaction |

| Push enteroscopy | Direct visualization and intervention | Invasive, endoscopic risk, patient discomfort, misses part of jejunum and ileum |

| Capsule endoscopy | Allows examination of most of the small bowel Noninvasive | No intervention capability Physician interpretation is time-consuming |

Management and Outcome

Treatment varies according to the bleeding's etiology and severity and patient comorbidities. Treatment options include endoscopic, angiographic, medical, and surgical therapies. Endoscopic therapies include thermal contact probes, laser coagulation, injection sclerotherapy, and banding.8

Thermal ablation of bleeding is the treatment most commonly used for accessible lesions. However, this technique carries some risks. During angiography, interventional radiologists inject vasopressin or embolization material into bleeding vessels. Complications from vasopressin injection have included myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, hypertension, and unintended thrombosis of arteries other than the target lesion.2 Medical therapies are one of the few options available for diffuse vascular lesions, but they have limited success rates.13

Gastrointestinal bleeding from arterial venous malformations traditionally is treated with combined estrogen and progesterone therapy. However, continuous use of hormones for months has considerable side effects, such as gynecomastia, loss of libido and feminization in men, and vaginal bleeding and breast tenderness in women. Hormone therapy theoretically increases the risk of thromboembolic events, although observational studies have not confirmed a risk increase.14 Hormone therapy is thought to benefit some patients with hereditary telangiectasias, von Willebrand's disease, or angiodysplasias in the setting of end-stage renal disease. Octreotide (Sandostatin), given at a dosage of 0.05 to 0.1 mg subcutaneously two to three times per day, has been successful in case studies.

Unless a single causative lesion is identified, surgical therapy should be a last resort. Patients with obscure bleeding often have multiple bleeding sites, and bleeding may persist after surgery. Supportive measures, including iron replacement, blood transfusion, and correction of coagulation or platelet disorders, may be indicated.