Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(6):717-724

Patient information: See related handout on aortic stenosis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Aortic stenosis is the most important cardiac valve disease in developed countries, affecting 3 percent of persons older than 65 years. Although the survival rate in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis is comparable to that in age-and sex-matched control patients, the average overall survival rate in symptomatic persons without aortic valve replacement is two to three years. During the asymptomatic latent period, left ventricular hypertrophy and atrial augmentation of preload compensate for the increase in afterload caused by aortic stenosis. As the disease worsens, these compensatory mechanisms become inadequate, leading to symptoms of heart failure, angina, or syncope. Aortic valve replacement should be recommended in most patients with any of these symptoms accompanied by evidence of significant aortic stenosis on echocardiography. Watchful waiting is recommended for most asymptomatic patients, including those with hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. Patients should be educated about symptoms and the importance of promptly reporting them to their physicians. Serial Doppler echo-cardiography is recommended annually for severe aortic stenosis, every one or two years for moderate disease, and every three to five years for mild disease. Cardiology referral is recommended for all patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis, those with severe aortic stenosis without apparent symptoms, and those with left ventricular dysfunction. Many patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis have concurrent cardiac conditions, such as hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease, which should also be carefully managed.

Aortic valve stenosis affects 3 percent of persons older than 65 years and leads to greater morbidity and mortality than other cardiac valve diseases.1 The pathology of aortic stenosis includes processes similar to those in atherosclerosis, including lipid accumulation, inflammation, and calcification.2 The development of significant aortic stenosis tends to occur earlier in those with congenital bicuspid aortic valves.3 Although the survival rate in asymptomatic patients is comparable to that in age-and sex-matched control patients, survival notably worsens after symptoms appear.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography is recommended in patients with classic symptoms of aortic stenosis accompanied by a systolic murmur and in asymptomatic patients with a grade 3/6 or louder systolic murmur. | C | 19 |

| Aortic valve replacement is the only effective treatment for patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. | B | 25, 26 |

| Watchful waiting is recommended for most patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis, including those with severe disease. | B | 28, 30, 31 |

| Serial Doppler echocardiography is recommended annually for severe aortic stenosis, every one to two years for moderate disease, and every three to five years for mild disease. | C | 19 |

| Aspirin prophylaxis should be considered in adults with a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease of 6 percent or greater, which is common with aortic stenosis. | A | 40 |

| Intensive lipid-lowering therapy has not been shown to stop the progression of calcific aortic stenosis and is not recommended in the absence of other indications for statin therapy. | C | 44 |

Pathophysiology and Natural History

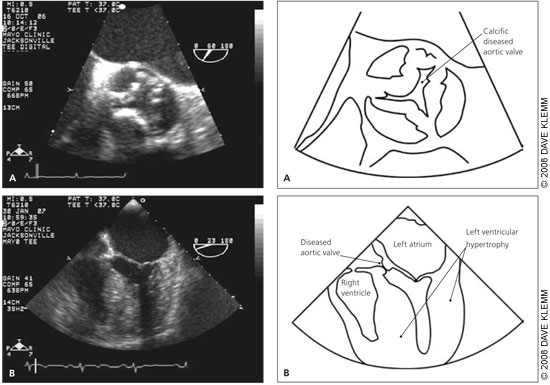

The natural history of aortic stenosis involves a prolonged latent period, during which progressive worsening of left ventricular (LV) outflow obstruction leads to hypertrophic changes in the left ventricle.4,5 As the aortic valve area becomes less than one half its normal size of 3 to 4 cm2 (about the size of a nickel), a measurable pressure gradient between the left ventricle and ascending aorta may be detected on echocardiography or by direct measurement at cardiac catheterization.6 This change reflects compensatory increases in LV pressures that contribute to the maintenance of adequate systemic pressures. One consequence is LV hypertrophy with subsequent diastolic dysfunction and increased resistance to LV filling.7,8 Thus, a strong left atrial contraction is needed to provide sufficient LV diastolic filling and support adequate stroke volume.9 Increasing overall myocardial contractility and augmenting preload with an increased atrial kick preserve LV systolic function, typically while the patient remains asymptomatic.

As aortic stenosis worsens, with the aortic valve area decreasing to 1 cm2 or less (about the size of the head of a golf tee),10 changes in LV function may no longer be adequate to overcome the outflow obstruction and maintain systolic function, even when complemented by an increase in preload. The resulting impairment in systolic function, alone or combined with diastolic dysfunction, may lead to clinical heart failure. Progressive LV hypertrophy from aortic stenosis also leads to increased myocardial oxygen needs11; concurrently, myocardial hypertrophy may compress the intramural coronary arteries as they carry blood toward the endocardium. These changes along with reduced diastolic filling of the coronary arteries may result in classic angina, even in the absence of coronary artery disease (CAD).12 In addition, as aortic stenosis becomes severe, cardiac output no longer increases with exercise.13 In this setting, a drop in systemic vascular resistance that normally occurs with exertion may lead to hypotension and syncope.14–16

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Classic symptoms of aortic stenosis include dyspnea and other symptoms of heart failure, angina, and syncope. The onset of these classic symptoms indicates hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis and is a critical point for making management decisions. It is also important to recognize that presentations may vary. Some patients with severe aortic stenosis, especially older patients, may present more subtly and initially experience a decrease in exertional tolerance without recognizing the classic symptoms. Others may have a more acute presentation, sometimes with symptoms precipitated by concurrent medical conditions. For example, new-onset atrial fibrillation with a resultant decrease in atrial filling may lead to symptoms of heart failure, or initiation of vasodilator medications may cause syncope.

A classic physical finding of aortic stenosis is a harsh, crescendo-decrescendo systolic murmur that is loudest over the second right intercostal space and radiates to the carotid arteries. This may be accompanied by a slow and delayed carotid upstroke, a sustained apical impulse, and an absent or diminished aortic second sound. However, in older persons, the murmur may be less intense and often radiates to the apex instead of to the carotid arteries. Also, with an increased incidence of atherosclerosis and hypertension in older persons, the classic carotid pulse changes may be masked. It is difficult to rule out aortic stenosis with physical examination findings alone. Reliable auscultatory indicators of the absence of aortic stenosis include a grade 1/6 or softer systolic murmur, absence of a radiating systolic murmur heard over the head of the right clavicle, and presence of a split second heart sound.17,18

It is essential that primary care physicians consider aortic stenosis in adults who present with any of the classic symptoms accompanied by a systolic murmur. Older patients with vague complaints, such as fatigue or decreased exercise tolerance, and asymptomatic patients undergoing preoperative medical assessment should receive further evaluation when physical examination reveals a grade 2/6 or louder systolic murmur. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) practice guidelines recommend echocardiography in asymptomatic patients with a grade 3/6 or louder systolic murmur.19

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

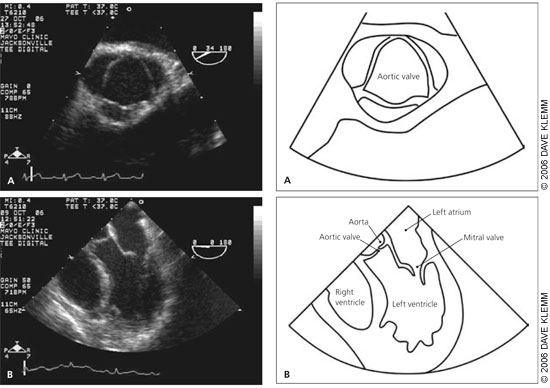

Doppler echocardiography is the recommended initial test for patients with classic symptoms of aortic stenosis.19 It is helpful for estimating aortic valve area, peak and mean transvalvular gradients, and maximum aortic velocity. These are the primary measures for assessing disease severity, and they have been well validated compared with measurement obtained with cardiac catheterization.20

Echocardiography also provides useful information about LV function, left ventricular filling pressure, and coexisting abnormalities of other valves. Guidelines for relating these hemodynamic measures to severity of aortic stenosis are presented in Table 1.19 Isolated aortic stenosis rarely becomes symptomatic until the aortic valve area is less than 1 cm2, the mean gradient is greater than 40 mm Hg, or the aortic jet velocity is greater than 4 m per second.

| Severity | Aortic jet velocity (m per second) | Mean gradient (mm Hg) | Aortic valve area (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 2.5 | — | 3 to 4 |

| Mild | 2.5 to 2.9 | < 25 | 1.5 to 2 |

| Moderate | 3 to 4 | 25 to 40 | 1 to 1.5 |

| Severe | > 4 | > 40 | < 1 |

Treatment

Aortic valve replacement is the only effective treatment for hemodynamically significant aortic stenosis. The surgery has an average perioperative mortality rate of 4 percent21–23 and a risk of prosthetic valve failure of approximately 1 percent per year.24 Figure 3 is an algorithm for the management of severe aortic stenosis.19

SYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Mortality dramatically increases after aortic stenosis becomes symptomatic. The average overall survival rate is two to three years in symptomatic patients without surgical treatment. Among older members of this population, one- and three-year mortality rates of 44 and 75 percent, respectively, have been reported.24 Although there are no prospective randomized trials comparing aortic valve replacement with medical management, retrospective observational studies have shown that surgical repair leads to significant improvement in survival, usually accompanied by symptom improvement.25,26 The 10-year survival rate in Medicare-age patients after aortic valve replacement is almost identical to that in age- and sex-matched persons who do not have aortic stenosis.27 Although these observational studies may have limitations, such as selection bias, a greater than fourfold difference in survival between surgically and medically treated patients supports the well-accepted recommendation that aortic valve replacement should be performed promptly in symptomatic patients.19 Additionally, it is unlikely that prospective randomized trials will be completed.

In symptomatic patients with echocardiographic measures consistent with severe aortic stenosis, symptoms must be presumed to be a result of aortic stenosis, even if other potentially causative conditions, such as CAD, are present. However, if echocardiographic findings suggest only moderate aortic stenosis, further diagnostic testing (e.g., coronary angiography, pulmonary function testing, arrhythmia evaluation) may be needed.

ASYMPTOMATIC PATIENTS

Aortic valve replacement is also recommended for asymptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis accompanied by LV systolic dysfunction (i.e., ejection fraction of less than 50 percent). When severe aortic stenosis is shown to be the primary pathology in this setting, aortic valve replacement is a lifesaving therapy and improves LV function.20,28,29

However, watchful waiting is recommended in most asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis, including those with severe disease. Survival in patients with aortic stenosis that is managed with watchful waiting is comparable to that in patients without aortic stenosis. Additionally, the surgical risk outweighs the approximately 1 percent annual risk of sudden death in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis. Attempts have been made to identify those who are more likely to have poor outcomes without “early” aortic valve replacement. Patients with very severeaortic stenosis (aortic valve area of 0.6 cm2 or less or an aortic jet velocity of 5 m per second or more), a more rapid increase in aortic jet velocity over time (0.3 m per second or more per year), or severe valve calcification have a high risk of developing symptoms and of needing aortic valve replacement within the next one to two years. High-risk patients, including patients who do not live near a medical care facility, may need closer monitoring or consideration of early valve replacement if the predicted operative mortality rate is 1 percent or less (i.e., in patients 70 years or younger without significant comorbidities).28,30,31

It is important to distinguish patients who are truly asymptomatic from those who have a routine activity level that has decreased to below their symptom threshold. This is especially important in older patients who may attribute their symptoms to normal aging or concurrent illness. When the symptom status is unclear, ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that exercise stress testing be performed under the direct observation of an experienced cardiologist.19 Aortic valve replacement should be considered if symptoms occur when the patient is at less than 80 percent of the predicted maximum heart rate or if the patient has an abnormal blood pressure response.32–34 Although exercise stress testing to detect concurrent CAD or to determine exercise tolerance is safe in patients with mild to moderate aortic stenosis, some cardiologists may be reluctant to perform the tests in those with significant aortic stenosis because of the risk of death during the test.

MONITORING AND REFERRAL

Watchful waiting until symptoms are detected is appropriate in most patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. ACC/AHA guidelines recommend that serial Doppler echocardiography be performed annually for severe aortic stenosis, every one to two years for moderate aortic stenosis, and every three to five years for mild aortic stenosis.19 Because symptoms are the best indicator of hemodynamic significance, a careful patient history should be obtained at regular intervals. Most importantly, patients should be educated about symptoms and the importance of promptly reporting them to their physicians. Cardiology referral is recommended for all patients with symptomatic aortic stenosis, for patients with aortic stenosis accompanied by LV dysfunction, and for asymptomatic patients with very severe or rapidly progressive calcification. Cardiology evaluation should also be considered in patients with subtle or atypical presentations, such as decreased exercise tolerance or an episode of congestive heart failure precipitated by new-onset anemia.

Medical Management During Watchful Waiting

No medical treatments have been proven to delay the progression of aortic valve disease or to improve survival. However, many patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis have concurrent cardiac conditions, including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and CAD; these conditions should be carefully controlled.19,28

HYPERTENSION

Approximately 40 percent of patients with aortic stenosis also have hypertension.28,35 With concurrent hypertension, LV afterload is elevated as a result of the “double load” that is created by aortic stenosis plus increased vascular resistance. Because it appears that the degree of valvular opening and stroke volume can increase in response to afterload reduction, treatment of hypertension is recommended in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis.36–38 However, patients with aortic stenosis can be particularly sensitive to the manipulation of preload, contractility, or systemic vasomotor tone.39

Blood pressure–lowering agents should be initiated at low doses and gradually titrated to achieve the desired effect. Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are well tolerated, improve effort tolerance, and reduce dyspnea in symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis.38 However, routine use of ACE inhibitors in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis cannot be recommended at this time. Second-generation dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers do not appear to depress LV function, as older calcium channel blockers do, and may be safe to use in patients with aortic stenosis. Diuretics should be used with caution because of the potential for reducing LV diastolic filling, which may reduce cardiac output. Peripheral alpha-blocker use may lead to hypotension or syncope and should be avoided.

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

Atrial fibrillation occurs in 5 percent of patients with aortic stenosis. Its presence may make echocardiographic assessment of aortic stenosis more challenging. Newonset atrial fibrillation may precipitate heart failure in a previously asymptomatic patient with significant aortic stenosis. Heart rate control is important to allow time for optimal diastolic filling. However, physicians should be aware of the possible hemodynamic effects of some rate-controlling medications in patients with aortic stenosis. In particular, beta blockers and rate-slowing calcium channel blockers may depress LV systolic function.

CORONARY RISK REDUCTION

Concurrent CAD is common in patients with aortic stenosis. ACC/AHA guidelines recommend evaluation and modification of cardiac risk factors in these patients.19 This includes discontinuation of tobacco use, initiation of aspirin prophylaxis in adult patients with a 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease 6 percent or greater, and participation in regular exercise.40 Patients with mild aortic stenosis should not be restricted from physical activity. Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe aortic stenosis should avoid competitive or vigorous activities that involve high dynamic and static muscular demands, although other forms of exercise are safe.19,41

Although initial observational studies suggested a significantly lower rate of aortic stenosis progression in patients treated with statins,42,43 a more recent randomized prospective study showed no statistical difference in hemodynamic progression of aortic stenosis between patients receiving aggressive atorvastatin (Lipitor) therapy and those receiving placebo.44 Because these studies were relatively small, it is too early to draw firm conclusions about the value of statin therapy for aortic stenosis. Larger prospective studies are expected to conclude in 2009.45

Finally, antimicrobial prophylaxis for bacterial endocarditis is recommended in patients who have undergone aortic valve replacement, but is no longer recommended for patients with aortic stenosis or other acquired valve diseases.46