Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(9):977-983

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Diverticular bleeding is a common cause of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Patients typically present with massive and painless rectal hemorrhage. If bleeding is severe, initial resuscitative measures should include airway maintenance and oxygen supplementation, followed by measurement of hemoglobin and hematocrit levels, and blood typing and crossmatching. Patients may need intravenous fluid resuscitation with normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution, followed by transfusion of packed red blood cells in the event of ongoing bleeding. Diverticular hemorrhage resolves spontaneously in approximately 80 percent of patients. If there is severe bleeding or significant comorbidities, patients should be admitted to the intensive care unit. The recommended initial diagnostic test is colonoscopy, performed within 12 to 48 hours of presentation and after a rapid bowel preparation with polyethylene glycol solutions. If the bleeding source is identified by colonoscopy, endoscopic therapeutic maneuvers can be performed. These may include injection with epinephrine or electrocautery therapy. If the bleeding source is not identified, radionuclide imaging (i.e., technetium-99m-tagged red blood cell scan) should be performed, usually followed by arteriography. For ongoing diverticular hemorrhage, other therapeutic modalities such as selective embolization, intra-arterial vasopressin infusion, or surgery, should be considered.

Diverticular bleeding is the source of 17 to 40 percent of lower gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage in adults, making it the most common cause of lower GI bleeding.1 In one study of 1,593 patients with diverticulosis, severe life-threatening diverticular hemorrhage occurred in 3.1 percent of patients.2 Most diverticular bleeding is self-limited, although it should be suspected in patients with massive and painless rectal hemorrhage. In adults older than 65 years, diverticular hemorrhage can lead to significant morbidity, especially in those with hemodynamic instability and comorbid conditions, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal insufficiency, and coronary artery disease.1,3 This review summarizes current recommendations for the management of diverticular bleeding in adults.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Severe postural dizziness and a postural pulse increase of at least 30 beats per minute are accurate indicators of moderate to severe blood loss. | C | 10 |

| Nasogastric lavage, followed by upper GI endoscopy if aspirate is positive for frank blood, should be performed in patients with large amounts of ongoing GI blood loss to rule out upper GI bleeding. | C | 11, 12 |

| Colonoscopy is safe, has good diagnostic yield, and should be considered the initial procedure of choice to evaluate lower GI bleeding. | C | 11, 16–18 |

| Urgent colonoscopy is safe in the setting of lower GI bleeding. | B | 11, 16–18 |

| Technetium-99m-tagged red blood cell scanning or arteriography can be used in patients who have ongoing hemorrhage with nondiagnostic endoscopic evaluation. | C | 12, 25 |

| Endoscopic therapeutic maneuvers, such as epinephrine injection or electrocautery therapy, can be used to treat diverticular bleeding. | B | 12, 25 |

| Patients should avoid using aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs because of their association with diverticular bleeding. | C | 37 |

| Fiber supplementation (32 g per day) and increasing levels of physical activity may prevent the progression of diverticular disease. | B | 38–40 |

Pathogenesis

Diverticula develop at sites of weaknesses in the colonic wall that occur where the vasa recta penetrate the circular muscle layer.4 As a diverticulum herniates, the vasa recta drape over the dome of the diverticulum and become susceptible to trauma and disruption.5 Inflammatory changes are not seen histologically, and diverticulitis does not usually coexist with diverticular bleeding.5 Although diverticula typically occur throughout the colon, diverticular bleeding tends to occur in the thinner-walled ascending (right) colon.6

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with diverticular bleeding usually present with abrupt onset of painless rectal hemorrhage.7 Occasionally, patients may present with mild abdominal cramping or the urge to defecate, secondary to blood within the colon.7,8 The stool may be bright red to dark maroon in color,9 and is often mixed with gelatinous clot.7 Patients may have a history of diverticulosis or diverticular bleeding.1 Table 1 lists possible causes of lower GI bleeding.1

| Diagnosis | Distinguishing features | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diverticular bleeding | Acute, severe, painless bleeding in the setting of known or suspected diverticular disease | 17 to 40 | |

| Angiodysplasia | Recurrent, painless bleeding episodes; can be chronic, leading to iron deficiency anemia | 2 to 30 | |

| Colitis | 9 to 21 | ||

| Ischemic colitis | Self-limited, bloody diarrhea followed by acute lower abdominal pain in patients with cardiac risk factors | ||

| Infectious colitis | Bloody diarrhea with fever and high-risk diet or previous antibiotic use | ||

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Bloody diarrhea associated with recurrent abdominal pain and weight loss | ||

| Colon cancer | Slow, chronic blood loss with change in bowel habit or iron deficiency anemia | 11 to 14 | |

| Postpolypectomy or post-endoscopic biopsy bleeding | Self-limited bleeding occurring within 30 days of a previous polypectomy or biopsy | 11 to 14 | |

| Hemorrhoids | Bleeding associated with bowel movements and anal pruritus; usually painless, but pain may be present with thrombosed hemorrhoids | 4 to 10 | |

| Upper GI bleeding | Elevated blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio, or positive nasogastric aspirate for blood | 0 to 11 | |

Patients may have a normal blood pressure and pulse if the bleeding has stopped. If bleeding is persistent and severe, patients may be tachycardic, hypotensive, or may exhibit orthostatic hypotension, which is defined as a postural pulse increase of 30 beats per minute or a postural systolic blood pressure decrease of 20 mm Hg.10 Severe postural dizziness and a postural pulse increase of at least 30 beats per minute are accurate indicators of acute blood loss of more than 630 mL, with a sensitivity of 97 percent and specificity of 98 percent (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 48; negative likelihood ratio [LR–] = 0.02).10 Late signs of severe blood loss include poor skin turgor, dry skin, and altered level of consciousness. The abdominal examination is usually normal but may demonstrate tenderness to palpation. Blood is typically found during rectal examination. Nasogastric lavage should be performed in patients passing large amounts of bright red- to dark maroon-colored stool because 10 to 15 percent of such hemorrhage is from an upper GI source.11,12 Upper endoscopy should be performed if frank blood is aspirated from nasogastric lavage.

INITIAL RESUSCITATIVE MEASURES

If a patient has unstable vital signs or presents with severe bleeding, rapid assessment and resuscitation should precede the diagnostic evaluation. Resuscitative measures include maintenance of the airway, oxygen supplementation, and placement of two large-bore intravenous lines, with subsequent intravenous fluid resuscitation using normal saline or lactated Ringer's solution. Laboratory evaluation includes coagulation studies; measurement of hemoglobin, hematocrit, and serum electrolyte levels; and determination of blood urea nitrogen-to-creatinine ratio.13 When abnormal, the ratio (especially if 33 or less) is helpful for ruling out lower GI bleeding with a sensitivity of 96 percent and a specificity of 17 percent (LR+ = 1.2; LR− = 0.2).13 Patients should be typed and crossmatched for packed red blood cells, and transfusion initiated based on the severity of the patient's clinical situation and comorbidities. Admission to the intensive care unit is recommended if the patient has significant comorbid conditions, has postural blood pressure changes, remains hemodynamically unstable, or requires transfusion following initial resuscitative measures.1,3

Diagnostic Testing

Diagnostic test selection is determined in part by local expertise and test availability. Methods to evaluate the lower GI tract for bleeding include direct visualization with a colonoscope, radionuclide imaging, and arteriography. Figure 11 provides an algorithmic approach to lower GI bleeding, and Table 2 lists advantages and disadvantages of these tests.

| Test | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Colonoscopy | Precise localization of bleeding and potential therapeutic intervention | Poor visualization in unprepared or massively bleeding patient; risk of sedation |

| Excludes other causes of GI bleeding | ||

| Radionuclide imaging | Noninvasive; excellent sensitivity | Regional localization only; must be performed during active bleeding; no potential for therapeutic intervention |

| Arteriography | Does not require bowel preparation; precise anatomic localization | Must be performed during active bleeding; risk of intestinal infarction |

COLONOSCOPY

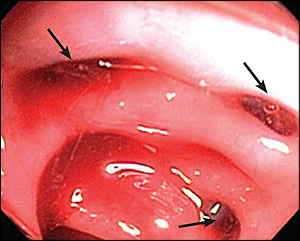

In patients with lower GI bleeding, the initial diagnostic procedure of choice is colonoscopy. During the procedure, the colonoscopist evaluates the colon for mucosal changes, infectious pathology, colitis, and ischemic changes to exclude these diagnoses. Colonoscopy should be performed within 12 to 48 hours of presentation and after colonic lavage with purge preparation (1 L polyethylene glycol solution every 30 to 45 minutes for at least two hours or until there is clear effluent). Colonic diverticula associated with bright red- to maroon-colored stool with clots are the most common findings on colonoscopy and are suggestive of, but not diagnostic for, diverticular bleeding in the absence of other pathologic findings. Active bleeding or stigmata of hemorrhage (visible vessel or pigmented protuberance) are identified in only 10 to 20 percent of colonoscopic examinations for diverticular bleeding.14 When present, these findings are associated with a high risk of continued or recurrent bleeding.15

The advantage of colonoscopy over other diagnostic modalities is direct visualization, allowing for exclusion of other etiologies of lower GI bleeding, as well as for immediate therapy. Colonoscopy is safe and effective, with a diagnostic yield of 69 to 80 percent in acute lower GI bleeding.11,16–18 In a review of four studies with 549 urgent colonoscopies performed for lower GI bleeding, only one complication (diverticulum perforation) was reported.11,16–18 Figure 2 shows a colonoscopic image of a blood-filled colon with clots and diverticula.

RADIONUCLIDE IMAGING

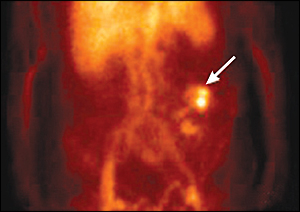

Patients with ongoing hemorrhage for whom colonoscopy has failed to localize the site of bleeding should have a nuclear medicine technetium-99m-tagged red blood cell scan. In this study, red blood cells obtained from the patient are “tagged” with a radioactive isotope and reinjected into the patient. The radiolabeled cells are then detected with a nuclear medicine camera. If GI bleeding is present, the radiolabeled red blood cells are detected in the lumen of the intestines (Figure 3). The tagged cells circulate for 48 hours and offer the advantage of repeat scanning in a patient with rebleeding and a previous negative study.

Another advantage of a technetium-99m-tagged red blood cell scan is that it may detect a low bleeding rate (0.1 mL per minute or 144 mL per day) if bleeding is continuous.19 In lower GI bleeding, the likelihood of a positive scan is 51 to 59 percent; a positive scan has an accuracy of 75 to 97 percent in localization to a region of the abdomen.20,21 The technetium-99m-tagged red blood cell scan is often performed before arteriography, although there have been no studies evaluating the effectiveness of a nuclear medicine scan preceding arteriography. A negative scan generally suggests that arteriography will also fail to identify an active source of hemorrhage.

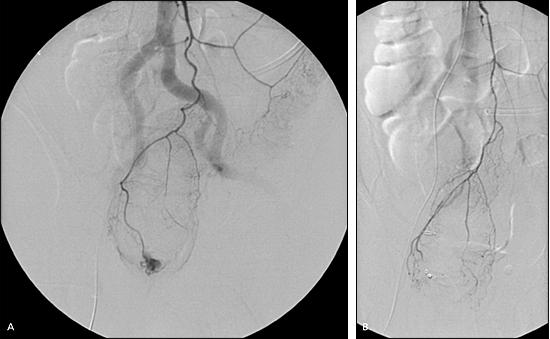

ARTERIOGRAPHY

Arteriography involves injection of contrast dye into the superior and inferior mesenteric arteries and their branches, which supply the ascending and descending colon with blood. An area of extravasation (contrast blush) can be seen in patients with active GI bleeding (Figure 4). The diagnostic yield of arteriography is 40 to 78 percent in active lower GI bleeding. Approximately 2 to 4 percent of patients who undergo diagnostic arteriography procedures develop a complication such as contrast allergy, contrast-induced renal failure, bleeding from the arterial puncture site, or embolism of a dislodged thrombus.22–24

Treatment

If bleeding stigmata, such as a protuberant vessel or pigmented spots, associated with a diverticulum are visualized during colonoscopy, therapy can be applied directly to this area. A small, retrospective study of endoscopic therapy in 10 patients found no rebleeding episodes using a combination of epinephrine injection and electrocautery therapy.12,25 Endoscopically placed clips (endoclips), fibrin sealant, and band ligation were shown to be effective in controlling diverticular bleeding in three small case series.26–28 If colonoscopy is not available or if it fails to reveal or control the bleeding source, further intervention is required. A tagged red blood cell scan is typically performed with attempts to localize the bleeding source and assist with targeted therapy by arteriography or surgery.

Intra-arterial vasopressin infusion during arteriography is successful in identifying bleeding in 72 percent of patients and controlling bleeding in 90 percent of patients. However, it is complicated by a 50 percent rebleeding rate and is seldom used in practice.29 Selective arteriography with therapeutic embolization is effective (76 to 100 percent of patients had controlled hemorrhage) and safe (less than 20 percent of patients experienced ischemia following embolization).30,31

Surgical intervention is rarely required because the bleeding is self-limited in 86 percent of patients, and there is a high rate of success at controlling bleeding by nonsurgical means.32 Indications for surgical intervention include large transfusion requirements (i.e., more than four units of packed red blood cells in a 24-hour period); recurrent hemorrhage that is refractory or not amenable to therapy; or hemodynamic instability that does not respond to medical therapy. In patients with uncontrolled bleeding requiring emergency surgery, mortality is high (10 to 20 percent), often because of hypotension and comorbid conditions.2,23,33 The surgical procedure of choice is directed segmental resection, which requires preoperative localization of hemorrhage. A subtotal colectomy performed for nonlocalized lower GI bleeding is associated with increased morbidity (37 percent) and mortality (11 to 33 percent), and should be performed only in patients with uncontrolled massive hemorrhage when there are no alternatives.29,34 The rebleeding rate in one study with a mean follow-up of one year was zero for subtotal colectomy, 14 percent for segmental resection with localization of bleeding, and 42 percent with segmental resection with nonlocalization of bleeding.35 Elective resection should be considered in patients with two or more episodes of diverticular hemorrhage.

Prognosis and Follow-up

Although most diverticular bleeding is self-limited and resolves spontaneously,8,34 blood loss is massive and rapid in 9 to 19 percent of patients.29,36 Patients at high risk of adverse outcomes include those with comorbid diseases, poor nutrition, or preexisting liver disease.1 Following the resolution of diverticular hemorrhage and the initial colonoscopy, surveillance colonoscopy is not recommended unless it is performed for other indications, such as colorectal cancer screening. The use of aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is associated with an increased risk of diverticular bleeding (odds ratio = 1.9 to 18.4).37 To prevent progression of diverticular disease, patients should increase their dietary fiber intake or begin fiber supplementation (32 g per day), and increase their level of physical activity.38–40 Obesity (body mass index greater than or equal to 30 kg per m2) is a significant risk factor for diverticular bleeding (relative risk = 2.0).41 Avoidance of certain nuts, corn, or popcorn to prevent complications is no longer recommended in patients with diverticular disease.42