A more recent article on HIV-associated complications is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2011;83(4):395-406

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection often develop multiple complications and comorbidities. Opportunistic infections should always be considered in the evaluation of symptomatic patients with advanced HIV/AIDS, although the overall incidence of these infections has decreased. Primary care of HIV infection includes the early detection of some complications through screening at-risk and symptomatic patients with routine laboratory monitoring (e.g., comprehensive metabolic and lipid panels) and validated tools (e.g., the HIV Dementia Scale). Treatment of many chronic complications is similar for patients with HIV infection and those without infection; however, combination antiretroviral therapy has shown benefit for some conditions, such as HIV-associated nephropathy. For other complications, such as cardiovascular disease and lipoatrophy, management may include switching antiretroviral regimens to reduce exposure to HIV medications known to cause toxicity.

As the prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and AIDS increases, and as survival rates improve with combination antiretroviral therapy, more primary care physicians are treating patients with HIV infection. Additionally, more than 20 percent of patients with HIV infection remain undiagnosed, and may initially present with AIDS-defining illnesses.1 Although the overall incidence of many opportunistic infections has decreased with effective chemoprophylaxis and combination antiretroviral therapy,2 prompt recognition and appropriate management are imperative to decrease mortality related to these conditions. Primary care management of HIV infection includes preventing and treating opportunistic infections, monitoring antiretroviral therapy, and treating chronic HIV-related complications.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with HIV infection who have new cognitive, behavioral, or motor abnormalities should be screened for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. | C | 12, 13 |

| Management of cardiovascular risk and dyslipidemia in patients with HIV infection should be based on guidelines from the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III. | C | 24 |

| At the time of HIV diagnosis, patients should be screened for kidney disease, and a calculated estimate of renal function should be made. Patients at high risk of kidney disease should undergo annual screening. | C | 54 |

| Baseline screening for glucose and lipid disorders should be performed for all patients with HIV infection at the time of diagnosis, with fasting blood glucose levels and lipid profiles monitored routinely thereafter (i.e., every six to 12 months). | C | 24, 42 |

| Patients should be evaluated for potential drug interactions between antiretrovirals (particularly protease inhibitors) and commonly prescribed medications (e.g., statins, calcium channel blockers, antiepileptics). Interactions may lead to complications such as myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and possibly HIV treatment failure. | C | 66 |

Some complications of HIV infection are the direct result of long-term infection, whereas others are the indirect result of aging, antiretroviral therapy, or other patient factors. Physicians should always consider the patient's most recent CD4 lymphocyte count (and nadir, if known) and assess preexisting conditions, medication use, health behaviors, and recent exposures. Although many opportunistic infections (e.g., pneumocystosis, toxoplasmosis, cryptococcosis) occur in patients with low CD4 lymphocyte counts, others (e.g., oral candidiasis, tuberculosis) can appear at any level.

This article reviews key complications in patients who have HIV infection, with an emphasis on neurologic, cardiopulmonary, and gastrointestinal disorders (Table 1). Important antiretroviral-associated complications are included because of their relevance to primary care physicians. Previously published articles provide additional information.3–5 Online resources also provide detailed information on the diagnosis and management of opportunistic infections (Table 2).

| System | Direct effect of HIV infection | Common complications | Associated pathogens | Antiretroviral treatment- related adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychiatric (Table 3) | HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, neuropathy, radiculopathy, myelopathy | Primary central nervous system lymphoma |

|

|

| Chronic psychiatric disorders | ||||

| Head and neck | HIV-associated retinopathy | Gingivitis, dental and salivary gland disease |

| |

| ||||

| Cardiovascular | HIV-associated cardiomyopathy | Cardiovascular disease, endocarditis |

|

|

| Atherosclerosis | ||||

| Pulmonary | HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer (including Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma) |

|

|

| Emphysema* | ||||

| Gastrointestinal (Table 4) | HIV-induced enteropathy | Viral hepatitis, lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, HPV- related malignancies |

|

|

| Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease* | ||||

| Renal/genitourinary | HIV-associated nephropathy | Chronic kidney disease not caused by HIV- associated nephropathy |

|

|

| Endocrine | Impaired lipid and glucose metabolism | — |

|

|

| HIV-associated wasting | ||||

| Lipodystrophy | ||||

| Hypogonadism,* premature ovarian failure | ||||

| Musculoskeletal | Myopathy, myositis | Osteopenia, osteoporosis, osteonecrosis |

|

|

| Hematologic or oncologic | Anemia of chronic disease | Lymphoma, multiple myeloma |

|

|

| Coagulation disorders* | ||||

| Dermatologic | Eosinophilic folliculitis* | Papulosquamous disorders (e.g., eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis); molluscum contagiosum; Kaposi sarcoma |

|

|

| AIDSinfo | |

| Telephone: 800-448-0440 | |

| Web site: http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov | |

| HIV InSite | |

| Web site: http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu | |

| Johns Hopkins Point-of-Care Information Technology—HIV guide | |

| Web site: http://www.hopkins-aids.edu | |

| NAM Aidsmap | |

| Web site: http://www.aidsmap.com | |

Many HIV-associated complications, such as dyslipidemia, are familiar to primary care physicians. Managing these complications is often possible without extensive input from an HIV expert, although special attention should be given to patients taking antiretroviral drugs because of polypharmacy. Primary care physicians should also include preventive care, health promotion (e.g., safe sex education), and psychosocial assessments as part of routine care for all patients with HIV infection.

Neuropsychiatric System

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM COMPLICATIONS

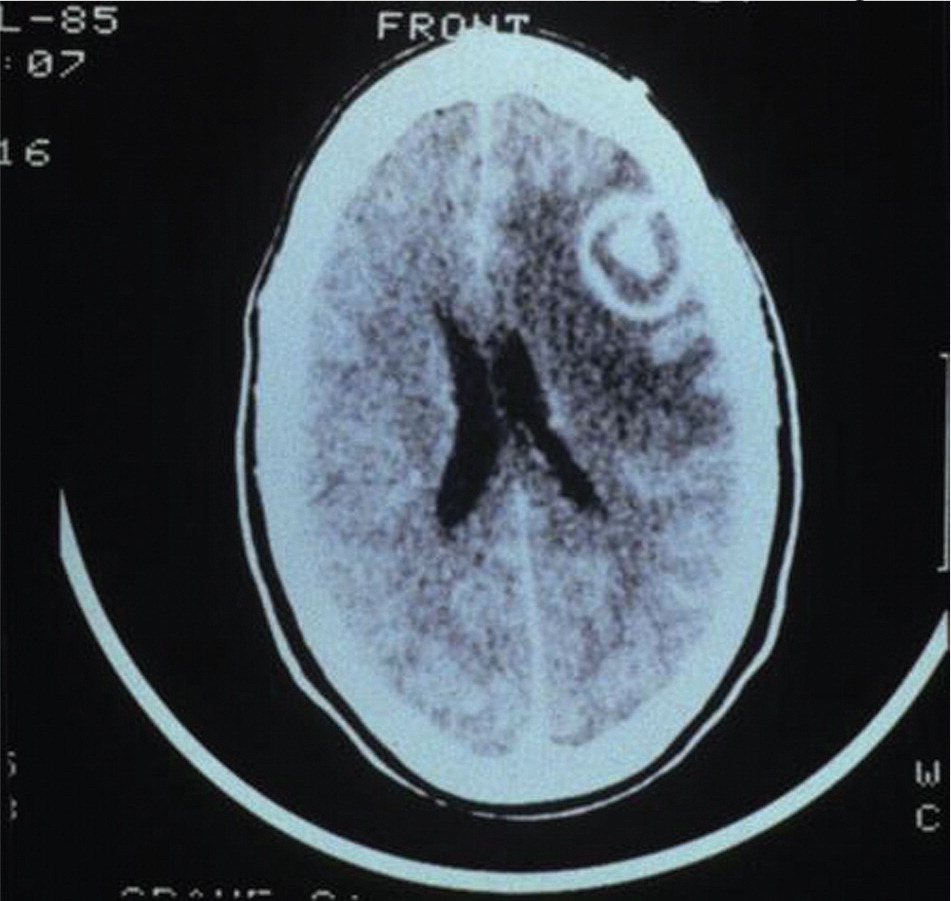

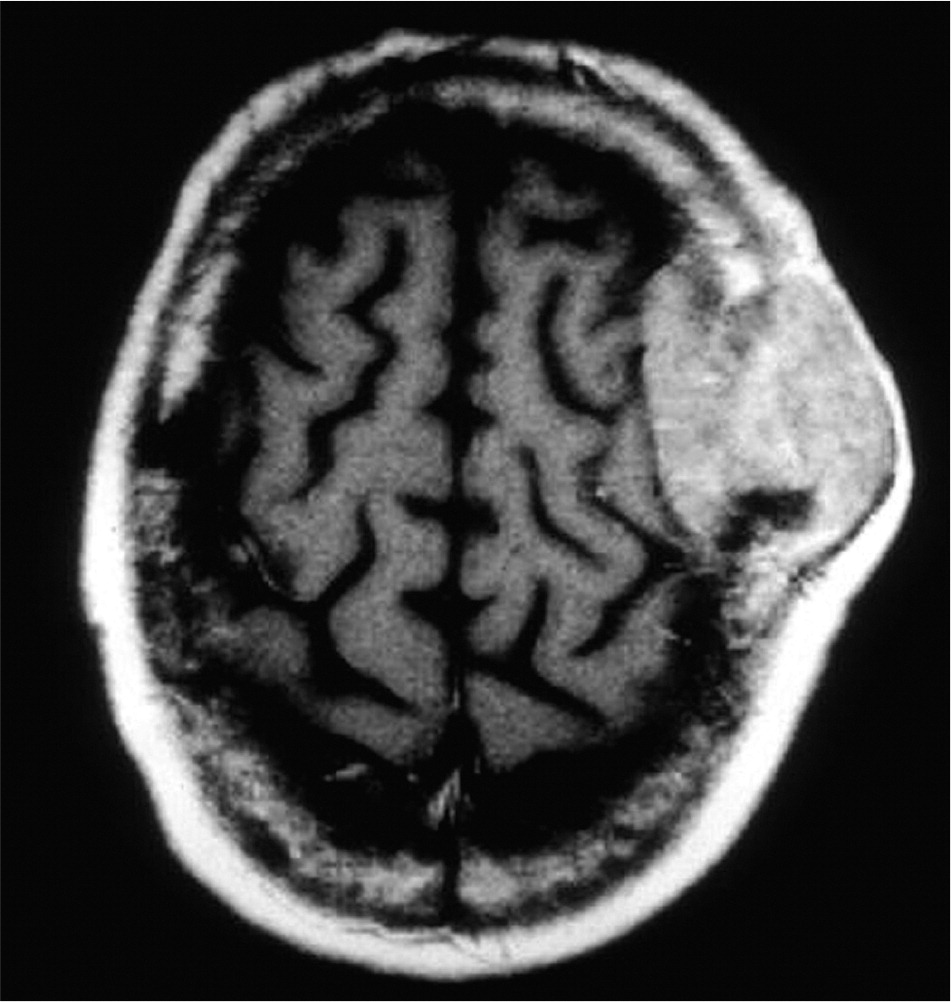

Advanced HIV infection can lead to opportunistic infections of the brain and spinal cord (Table 36 ). Well-known pathogens include Toxoplasma gondii (Figure 1), Cryptococcus neoformans, and JC virus. Primary central nervous system lymphoma may also affect severely immunocompromised patients (Figure 2). Infections and malignancy cause variable neurologic symptoms, usually reflecting the location and severity of disease. For example, patients with solitary lesions often present with headache or focal deficits, whereas patients with increased intracranial pressure from substantial masses (with or without edema) may have visual disturbances, nausea, or altered consciousness. Patients with meningitis or encephalitis generally present with one or more of the following: fever, headache, neck pain or stiffness, altered mental status, or seizure. Symptoms of myelopathy include weakness and sensory changes; upper motor neuron signs, such as spasticity and hyperreflexia, may also be found.

| Complication* | Signs and symptoms | Typical CD4 lymphocyte count | Diagnostic evaluation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imaging | Serology | Microbiology/other | ||||

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | Focal neurologic deficits, confusion, occasional fever or headache; seizure or coma with progressive disease | < 50 per mm3 (0.05 × 109 per L) | Contrast MRI or CT usually shows one or more ring-enhancing lesions with edema, with or without mass effect | Serum toxoplasma immunoglobulin G is often positive (absence makes diagnosis less likely) | Brain biopsy is recommended if patients do not improve with empiric therapy | |

| CSF analysis is rarely performed | ||||||

| Cryptococcal meningoencephalitis (or cryptococcoma) | Headache, fever, confusion, altered mental status | < 50 per mm3 | — | Serum cryptococcal antigen is almost always positive | Fungal cultures and CSF or blood staining may yield organism | |

| CSF antigen may be elevated | ||||||

| Viral meningoencephalitis | In general: fever, headache, confusion, delirium, lethargy, focal deficits, occasionally seizure (virus-specific symptoms listed below) | — | — | — | PCR of CSF (or brain tissue), special staining, viral culture | |

| Cytomegalovirus | Worsening focal deficits | < 50 per mm3 | Periventricular enhancement on MRI | |||

| Herpes simplex virus | Behavioral, personality, or memory changes | < 200 per mm3 (0.20 × 109 per L) | Diffuse edema, occasionally shows necrosis of frontal and temporal lobes (MRI more sensitive than CT) | |||

| Electroencephalography often shows characteristic focal temporal abnormalities | ||||||

| Varicella zoster virus | Vasculitis, leading to stroke syndromes | Risk increases with lower CD4 count | Diffuse edema with demyelination, possible focal infarcts (MRI more sensitive than CT) | |||

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | Progressive focal deficits (e.g., cognitive decline, cranial nerve palsy, aphasia, ataxia, weakness or sensory loss, seizure); may progress to coma | < 200 per mm3 | Single or multiple white matter lesions with little to no enhancement and no edema or mass effect (MRI more sensitive than CT) | — | Brain biopsy is definitive but rarely performed | |

| PCR detection of JC virus in CSF helps confirm diagnosis | ||||||

| Neurosyphilis | Wide range of symptoms (e.g., behavioral and psychological abnormalities, delirium, dementia, focal deficits, stroke syndromes related to arteritis, ocular and auditory changes, meningitis, myelitis) | < 350 per mm3 (0.35 × 109 per L) | — | CSF VDRL test is specific but not sensitive; reactive test confirms diagnosis (nonreactive test does not exclude diagnosis) CSF treponemal tests (e.g., FTA-ABS) are sensitive but not specific; nonreactive test excludes diagnosis† | CSF typically shows elevated protein level and mononuclear pleocytosis (white blood cell count > 10 to 20 per μL [.01 to .02 × 109 per L]) | |

| Risk increases when serum rapid plasma reagin titer ≥ 1:32 | ||||||

| Primary central nervous system lymphoma | Focal neurologic deficits, headache, blurred vision, seizure, motor difficulty, personality or cognitive changes, confusion | Risk increases with lower CD4 count | Solitary white matter lesions on CT or MRI, often with mild edema and mass effect | — | Brain biopsy is definitive, although CSF examination for cytology, flow cytometry, and PCR testing may also be useful | |

| Multicentric lymphoma occurs less frequently | ||||||

| PET/SPECT is occasionally useful to differentiate from cerebral toxoplasmosis | ||||||

Research describes a spectrum of deficits (wider than previously thought) that arise from HIV-mediated neurotoxicity and inflammation, especially in patients with a history of low CD4 lymphocyte counts.7–9 Impairment ranges from mild (asymptomatic neurocognitive impairment) to severe (HIV-associated dementia). Collectively, these are termed HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV-associated dementia is an AIDS-defining condition involving deficits in at least two cognitive ability domains (e.g., memory, attention and concentration) and abnormalities in motor or neurobehavioral function that impair activities of daily living. Brief screening instruments are available, such as the HIV Dementia Scale (Figure 310,11 ),12 although extensive neuropsychological testing may be needed in some cases. Data are limited regarding treatment of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Researchers are investigating whether antiretroviral drugs with sufficient central nervous system penetration can significantly improve symptoms or prevent further cognitive decline. Antibacterials, antiinflammatories, and antioxidants have not shown benefit.

Evidence suggests that neurodegenerative disorders, such as early-onset Alzheimer disease, are increasing disproportionately in patients with HIV infection, even in those with well-controlled HIV disease.13,14 This, in addition to the potential impact of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, has fueled concerns that the aging population with HIV infection will be vulnerable to neurologic and functional decline and increasing frailty and disability.

OTHER NEUROPSYCHIATRIC COMPLICATIONS

HIV usually affects the peripheral neurologic system as neuropathy (i.e., distal sensory polyneuropathy) or radiculopathy (usually a lumbrosacral polyradiculopathy).15 These conditions may be exacerbated by antiretroviral drug use or other conditions (e.g., diabetes mellitus). Polyradiculopathy may also be caused by cytomegalovirus in patients with AIDS. Patients with distal sensory polyneuropathy generally present with symptoms of paresthesia, dysesthesia, or numbness of the bilateral extremities, whereas patients with lumbosacral radiculopathy typically experience radiating back pain, occasional asymmetric leg weakness, sacral or lower extremity sensory loss, and possible bowel or bladder dysfunction. Examination findings include decreased or absent deep tendon reflexes and impaired vibration/pinprick perception. In addition to a thorough neurologic examination, the diagnosis of peripheral neurologic system complications may require electromyography, nerve conduction studies, or magnetic resonance imaging of the brain or spinal cord to evaluate for central lesions and peripheral nerve root impingement. Occasionally, cerebrospinal fluid examination may be warranted to look for opportunistic pathogens.

Studies estimate that up to 50 percent of patients with HIV infection have concurrent chronic psychiatric and substance use disorders.16 Such conditions are not directly related to infection, but occasionally decrease quality of life and interfere with treatment adherence. Therefore, many HIV clinics routinely screen for these conditions at the initial visit and at regular intervals thereafter.

Cardiopulmonary System

CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS

Studies demonstrate higher rates of myocardial infarction and atherosclerosis in patients with HIV infection.17,18 HIV appears to independently increase the risk of cardiovascular disease via elevated cytokine levels, chronic vascular inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction.19 Traditional risk factors, such as smoking, are also prevalent in patients with HIV infection.20 Virally mediated vascular effects may then be compounded by lipid or metabolic changes caused by infection and antiretroviral use. For example, abacavir (Ziagen) has been widely investigated for direct cardiotoxicity.21–23 Currently, cardiac risk assessment and dyslipidemia recommendations for persons with HIV infection are based on the National Cholesterol Education Program, Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. In addition, some experts suggest that extra attention be paid to current and previous antiretroviral exposure (i.e., abacavir, protease inhibitors) when evaluating patients for cardiovascular disease.24 Ongoing studies are assessing the benefits of switching antiretroviral drugs25; however, the possibilities of new toxicities and virologic rebound must be weighed against traditional options (i.e., lipidlowering therapy).

Other HIV-associated cardiac complications (i.e., cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, and pericarditis) are still reported, although their incidence has decreased as combination antiretroviral therapy has become widespread.26 This decrease may be partly attributable to a reduction in opportunistic infections. Infective endocarditis occurs almost exclusively in those who use injection drugs.

PULMONARY COMPLICATIONS

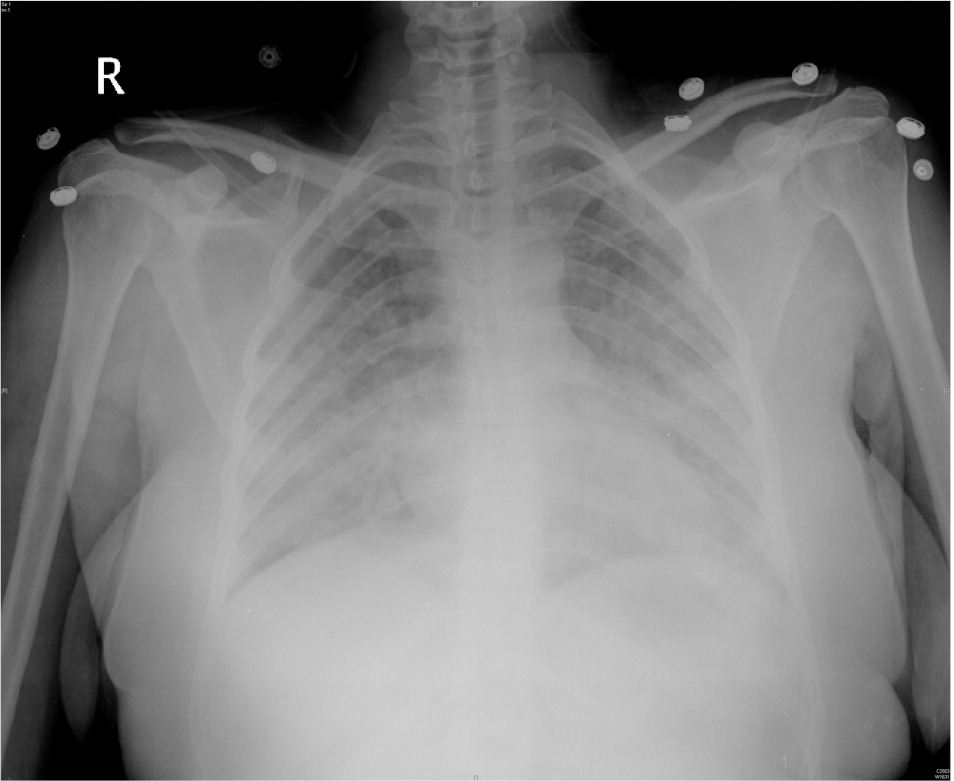

Pneumocystis jiroveci (formerly Pneumocystis carinii) pneumonia remains relatively common in patients with HIV infection, and may be the presenting manifestation of HIV in patients who have not yet been diagnosed.27 Patients with P. jiroveci pneumonia classically present with fever, progressive exertional dyspnea, and nonproductive cough. Although there are a wide variety of radiologic findings, chest radiography typically shows bilateral interstitial infiltrates (Figure 4). Empiric treatment is appropriate in patients with mild, classic symptoms and CD4 lymphocyte counts of 200 per mm3 (0.20 × 109 per L) or less. However, further diagnostic techniques (e.g., induced sputum examination, transbronchial biopsy with or without bronchoalveolar lavage) should be used if patients do not improve after four to five days of empiric therapy.28,29 Severe pneumococcal pneumonia and infections caused by atypical organisms (i.e., Legionella species) or other opportunistic pathogens should also be considered, depending on CD4 lymphocyte counts and geographic location.

Rates of pulmonary arterial hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and lung cancer have remained the same or increased in patients with HIV infection over the past few decades.30–33 Although the exact etiology of HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension is largely unknown, vascular pathologic changes and clinical presentation (e.g., exertional dyspnea, fatigue, cough, edema) are similar to those in patients without HIV infection. Initial evaluation involves electrocardiography and echocardiography. Imaging and pulmonary function tests can help exclude other diagnoses. Cardiac catheterization is considered the diagnostic standard to quantify pulmonary pressure and guide treatment, which may include diuretics, digoxin, calcium channel blockers, anticoagulants, and supplemental oxygen. Agents targeting the prostacyclin, nitric oxide, and endothelin pathways (i.e., epoprostenol (Flolan), sildenafil (Revatio), and bosentan (Tracleer) are also used. The effect of combination antiretroviral therapy on the clinical course and prognosis of HIV-associated pulmonary hypertension remains uncertain.

Additionally, research suggests that HIV accelerates emphysema-associated processes in patients who smoke, leading to earlier development and high rates of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.32 HIV also appears to raise the risk of lung cancer, even independent of smoking (one study reported a hazard ratio of 3.6).33 Because studies have yet to determine whether antiretroviral therapy alters chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer development in patients with HIV infection, tobacco cessation remains the most important preventive measure for those with HIV who smoke.

Gastrointestinal and Hepatic Systems

ORAL AND ESOPHAGEAL DISEASE

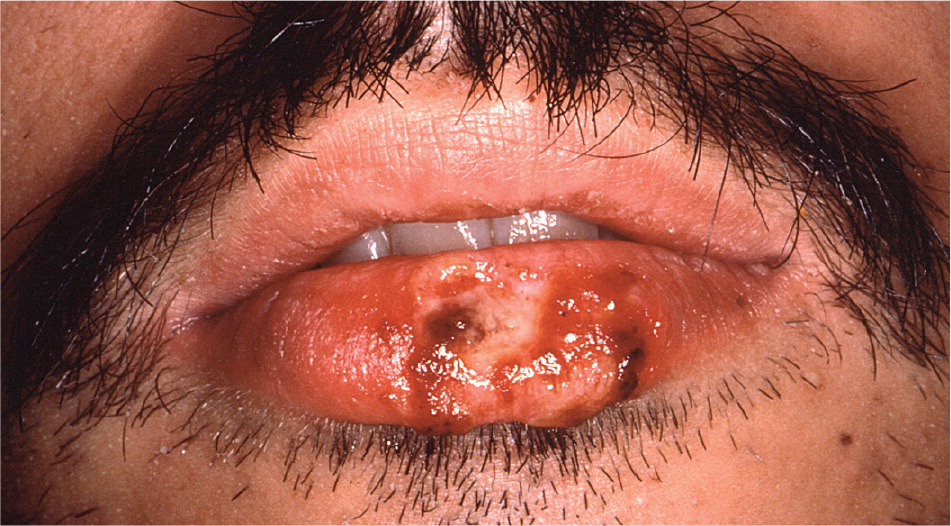

HIV-related upper digestive tract complications are well documented.34 Candidal infection often affects the oral cavity, leading to dysphagia or odynophagia (Figure 5), or the esophagus, manifesting as sharp or burning substernal discomfort. Aphthous ulcers and oral ulcers/esophagitis caused by cytomegalovirus or herpes simplex virus (Figure 6) may also occur, especially in patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts of 200 per mm3 or less. Diagnosis of these viral infections is made by histologic examination after biopsy; aphthous ulcers should be considered in patients with oral/esophageal ulcers only after excluding infections. Physicians should also routinely examine patients for oropharyngeal cancer, given the prevalence of oral human papillomavirus (11 to 37 percent), smoking, and alcohol use in patients with HIV infection.35,36

OTHER DIGESTIVE TRACT COMPLICATIONS

The assessment of gastrointestinal complications is often directed by the degree of immunosuppression and the nature and duration of symptoms (Table 46 ). Diarrhea is a common symptom in adults with HIV infection. In one sample, approximately 40 percent of patients reported at least one episode of diarrhea in the preceding month.37 HIV also directly invades various intestinal cell populations and disturbs gut motility by affecting the autonomic nervous system, leading to HIVassociated enteropathy.38 Slightly higher rates of inflammatory bowel disease have been reported in patients with HIV infection,39 although reasons for this are unclear.

| Complication* | Signs and symptoms | Typical CD4 lymphocyte count | Diagnostic evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbiology/histology | Other | |||

| Cytomegalovirus infection | Fever, anorexia, abdominal pain or bloating, watery diarrhea (occasionally bloody); possible perforation | < 50 to 100 per mm3 (0.05 to 0.10 × 109 per L) | Colonoscopy with biopsy to visualize mucosal erosion and ulcerations, and demonstrate intranuclear and intracytoplasmic viral inclusions | Mucosal tissue may be sent for cytomegalovirus antigen detection through immunostaining |

| Infection from Cryptosporidium species, microsporidia, or Isospora belli | Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, cramps, profuse watery (nonbloody) diarrhea; malabsorption is common | < 100 per mm3 | Stool or biopsy tissue for microscopic identification and staining | Cryptosporidium oocysts can be detected by direct immunofluorescence or ELISA |

| Determination of microsporidia can be made with transmission electron microscopy, special antibody staining, or PCR | ||||

| HIV-induced enteropathy (or AIDS enteropathy) | Chronic diarrhea, with occasional weight loss from malabsorption | More common in patients with advanced HIV disease (i.e., CD4 count < 200 per mm3 [0.20 × 109 per L]) | — | Diagnosis of exclusion |

| Intestinal malignancies (e.g., non-Hodgkin lymphoma, Kaposi sarcoma, anal squamous cell carcinoma) | Abdominal or rectal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, intestinal bleeding, malabsorption, weight loss if direct involvement | Tends to occur in patients with advanced HIV infection (i.e., CD4 count < 200 per mm3) | Endoscopy with biopsy | — |

| Extraluminal tumors may cause symptoms through indirect involvement (e.g., leading to obstruction) | ||||

| Fat malabsorption (pancreatic exocrine insufficiency) | Weight loss, abdominal bloating, steatorrhea, foul-smelling stools, flatulence | Can occur at any count | — | Quantitative: 72-hour stool fat analysis, fecal elastase |

| Qualitative: Sudan black B fat staining | ||||

| Proctitis and anorectal ulcers from sexually transmitted infections | Fecal urgency, crampy bowel movements, anorectal soreness, sensation of incomplete voiding, occasionally rectal bleeding or discharge | Can occur at any count | Swab (for Gram stain or culture) for sexually transmitted bacteria and viruses | Swab can also be obtained for PCR amplification |

| Proctosigmoidoscopy with biopsy may be needed | ||||

| Protease inhibitor-related adverse effects | Nausea, abdominal discomfort or bloating, loose nonbloody stools | Can occur at any count | — | Consider diagnosis after other causes have been ruled out |

| Symptoms usually occur soon after medication initiation | ||||

PANCREATIC AND HEPATOBILIARY COMPLICATIONS

HIV-associated pancreatitis is now primarily caused by antiretroviral use and hypertriglyceridemia, rather than opportunistic infections. Although acalculous cholecystitis may occur, the incidence of cholelithiasis does not appear to be increased by HIV.40 Chronic liver disease from viral or nonviral hepatitis has become a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV infection; patients should be screened for viral hepatitis at the time of HIV diagnosis.41–42 Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has also been recognized as an important complication of HIV, especially in patients with hepatitis C coinfection. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is associated with various factors, including visceral adiposity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and mitochondrial toxicity.43,44 Because traditional inflammatory biomarkers are often normal and ultrasonography is somewhat insensitive, new biomarker panels and imaging modalities (i.e., transient elastography) are being investigated.45 Treatment of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease currently focuses on reducing metabolic risk through lifestyle modifications (e.g., weight loss) and management of insulin resistance and hyperlipidemia. Hepatocellular carcinoma appears to affect persons who have HIV infection at younger ages compared with those who do not have HIV infection; therefore, surveillance sonography is recommended for at-risk persons, such as those with chronic hepatitis C or alcoholic cirrhosis.46,47

Genitourinary System

GENITAL INFECTIONS

Because the individual and public health consequences of untreated sexually transmitted infections in patients with HIV infection are considerable, prompt diagnosis and management of these infections are essential. Genital herpes increases the risk of HIV transmission; studies have yet to confirm whether suppressive herpes treatment reduces this risk.48,49 Management of most sexually transmitted infections in patients with HIV infection is similar to that for persons without HIV infection; however, higher doses of antivirals and a possibly longer duration of therapy are indicated for treating genital herpes in patients with HIV infection.50 Additionally, elevated rates of high-risk human papillomavirus subtypes are found in patients with HIV infection, increasing their risk of anogenital tract dysplasia.35

RENAL COMPLICATIONS

The spectrum of HIV-associated renal disease has evolved. Acute and subacute complications related to antiretroviral therapy, such as protease inhibitor–associated nephrolithiasis and nephrotoxicity from tenofovir (Viread) use, continue to occur. Rates of end-stage kidney disease caused by HIV-associated nephropathy have stabilized,51 whereas diabetes, hypertension, and hepatitis C are emerging as major risk factors for chronic kidney disease in patients with HIV infection.52,53

At the time of HIV diagnosis, patients should be screened for kidney disease with urinalysis, and a calculated estimate of renal function with creatinine clearance or glomerular filtration rate should be made. HIVassociated nephropathy should be considered in patients with proteinuria and progressively worsening renal function; diagnosis requires kidney biopsy. Treatment consists of combination antiretroviral therapy and angiotensinconverting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers, and possibly steroids. In patients with undetectable HIV viral loads and CD4 lymphocyte counts greater than 200 cells per mm3, kidney transplantation may be considered. Annual testing for kidney disease is recommended for high-risk patients (e.g., blacks; patients with CD4 lymphocyte counts less than 200 per mm3 or HIV viral load greater than 4,000 RNA copies per mL; patients with comorbid diabetes, hypertension, or hepatitis C).54

Metabolic and Endocrine Complications

INSULIN RESISTANCE, DIABETES, DYSLIPIDEMIA, AND LIPODYSTROPHY

Although abnormalities in glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, and adipose tissue distribution are multifactorial, insulin resistance, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and lipodystrophy can occasionally be attributed to antiretroviral therapy.55 These complications reflect complex interactions between the patient and traditional risk factors, medication effects, and infection (HIV causes chronic inflammation, immune system activation, etc.). Patients should be screened for glucose and lipid disorders at the time of diagnosis and routinely thereafter (i.e., every six to 12 months). Lipids should also be checked within three to six months of initiating new antiretroviral therapy.24,42 Management of insulin resistance and diabetes in patients with HIV infection does not differ significantly from management in other patients; treatment is primarily based on guidelines from the American Diabetes Association.56 If glucose-lowering medication is indicated, patients with HIV infection and diabetes who also have lipoatrophy may benefit from pioglitazone (Actos). Physicians may also consider switching antiretroviral medications to more glucose- or lipid-neutral regimens. Specific management of lipoatrophy includes thymidine analogue discontinuation, cosmetic procedures, or thiazolidinediones (statins are being investigated), whereas lipohypertrophy management includes lifestyle modifications, cosmetic procedures, and possibly metformin (Glucophage). Growth hormone–releasing factors are also being studied.

OTHER ENDOCRINE COMPLICATIONS

Disorders of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal and gonadal axes have been reported in patients with HIV infection. In addition to peripheral causes, central nervous system lesions can involve the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, leading to adrenal insufficiency and hypogonadism. Adrenal insufficiency is usually mild and may also be caused by direct HIV infection of the adrenals, disseminated opportunistic infections, malignancy, or medication use (e.g., systemic ketoconazole [Nizoral]). Testosterone deficiency is common,57 especially in men with advanced HIV infection or AIDS. Research also demonstrates that women with HIV infection commonly experience irregular menses and may be at higher risk of amenorrhea or premature ovarian failure.58

Musculoskeletal System

Studies estimate a three- to sixfold increased risk of reduced bone mineral density in patients with HIV infection.59 Preliminary work also suggests an increased prevalence of fractures.60 Various antiretrovirals have been associated with osteopenia and osteoporosis, although other factors (e.g., weight, nadir CD4 lymphocyte count, menopausal status, chronic steroid use) may play a role.61–64 Given the lack of data, osteoporosis screening for patients with HIV infection remains somewhat controversial. Some experts recommend screening at-risk patients (i.e., postmenopausal women, men older than 50 years) and treating based on risk calculation.65 Patients with HIV infection are also vulnerable to osteomalacia and osteonecrosis, the latter involving ischemic subchondral bone tissue death. Osteonecrosis typically manifests as joint pain or stiffness, particularly in the groin, hips, or shoulders. Plain radiography (Figure 7) is an appropriate first step, although magnetic resonance imaging is more sensitive.

Myopathy from older nucleoside analogues may now be less common because of the availability of newer agents. HIV also causes an autoimmune-mediated myopathy. Physicians should be especially careful with patients on antiretrovirals (particularly protease inhibitors), because coadministration of these drugs with commonly prescribed medications (e.g., statins, calcium channel blockers, antiepileptics) may lead to myopathy, rhabdomyolysis, and possibly HIV treatment failure.66