Am Fam Physician. 2016;93(5):371-378

Patient information: See related handout on aortic stenosis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Aortic stenosis affects 3% of persons older than 65 years. Although survival in asymptomatic patients is comparable to that in age- and sex-matched control patients, it decreases rapidly after symptoms appear. During the asymptomatic latent period, left ventricular hypertrophy and atrial augmentation of preload compensate for the increase in after-load caused by aortic stenosis. As the disease worsens, these compensatory mechanisms become inadequate, leading to symptoms of heart failure, angina, or syncope. Aortic valve replacement is recommended for most symptomatic patients with evidence of significant aortic stenosis on echocardiography. Watchful waiting is recommended for most asymptomatic patients. However, select patients may also benefit from aortic valve replacement before the onset of symptoms. Surgical valve replacement is the standard of care for patients at low to moderate surgical risk. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement may be considered in patients at high or prohibitive surgical risk. Patients should be educated about the importance of promptly reporting symptoms to their physicians. In asymptomatic patients, serial Doppler echocardiography is recommended every six to 12 months for severe aortic stenosis, every one to two years for moderate disease, and every three to five years for mild disease. Cardiology referral is recommended for all patients with symptomatic moderate and severe aortic stenosis, those with severe aortic stenosis without apparent symptoms, and those with left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Medical management of concurrent hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease will lead to optimal outcomes.

Aortic valve stenosis affects 3% of persons older than 65 years and is the most significant cardiac valve disease in developed countries.1 Its pathology includes processes similar to those in atherosclerosis, including lipid accumulation, inflammation, and calcification.2 The development of significant aortic stenosis tends to occur earlier in persons with congenital bicuspid aortic valves and in those with disorders of calcium metabolism, such as in renal failure.3 Although the survival rate in asymptomatic patients is comparable to that in age- and sex-matched control patients, it decreases rapidly after symptoms appear.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: AORTIC STENOSIS

In patients with aortic stenosis, the 10-year cardiovascular risk should be determined and the benefits and risks of statin therapy and aspirin prophylaxis should be discussed based on current guidelines.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement is recommended for patients who have an indication for aortic valve replacement but are at prohibitive surgical risk. Transcatheter valve replacement is also a reasonable alternative to surgical replacement in high-risk patients.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Transthoracic echocardiography is indicated when there is a loud unexplained systolic murmur, a single second heart sound, a history of a bicuspid aortic valve, or symptoms that might be caused by aortic stenosis. | C | 18–20 |

| Aortic valve replacement is the only treatment that improves mortality in patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis. | B | 28–32 |

| Watchful waiting is recommended for most patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis. | B | 20, 25, 34, 36 |

| In asymptomatic patients, serial Doppler echocardiography is recommended every six to 12 months in patients with severe aortic stenosis, every one to two years in those with moderate disease, and every three to five years in those with mild disease. | C | 20 |

| Antimicrobial prophylaxis for bacterial endocarditis is not recommended for patients with aortic stenosis unless they have undergone aortic valve replacement or have a history of endocarditis. | C | 49 |

Pathophysiology and Natural History

Aortic stenosis has a prolonged latent period, during which progressive worsening of left ventricular (LV) outflow obstruction leads to compensatory hypertrophic changes in the LV myocardium.4,5 The resultant increase in LV systolic function helps maintain adequate systemic pressures.6 However, LV hypertrophy may also lead to diastolic dysfunction and increased resistance to LV filling.7,8 Thus, a strong left atrial contraction may be needed to provide sufficient LV diastolic filling and to support adequate stroke volume.9 As aortic stenosis worsens, these adaptations become inadequate to overcome the outflow obstruction and maintain systolic function.10 Impaired systolic function, alone or combined with diastolic dysfunction, may lead to clinical heart failure. Similar symptoms may occur if the atrial kick is lost and diastolic filling time shortens, such as in atrial fibrillation with a rapid ventricular response.

Progressive LV hypertrophy from aortic stenosis may also result in increased myocardial oxygen needs11; concurrently, myocardial hypertrophy may compress the intramural coronary arteries as they carry blood toward the myocardium. These changes, along with reduced diastolic filling of the coronary arteries, may cause angina, even in the absence of coronary artery disease.12 In addition, as aortic stenosis becomes severe, cardiac output no longer increases with exercise.13 In this setting, a drop in systemic vascular resistance with exertion may lead to hypotension and syncope.14–16

Diagnosis

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

The cardinal symptoms of aortic stenosis include dyspnea and other symptoms of heart failure, angina, and syncope. Symptom onset identifies clinically significant stenosis and the need for urgent intervention. However, some patients with severe aortic stenosis—especially older patients—may not develop classic symptoms initially and instead only experience a decrease in exercise tolerance. Others may have a more acute presentation, sometimes with symptoms precipitated by concurrent medical conditions or treatments. For example, new-onset atrial fibrillation with a resultant decrease in atrial filling may lead to symptoms of heart failure, and initiation of vasodilator medications may cause syncope.

The classic physical finding of aortic stenosis is a harsh, late-peaking systolic murmur that is loudest over the second right intercostal space and radiates to the carotid arteries. This may be accompanied by a slow and delayed carotid upstroke, a sustained point of maximal impulse, and an absent or diminished aortic second sound. However, in older persons, the murmur may be less intense and often radiates to the apex instead of to the carotid arteries. Also, the classic carotid pulse changes may be masked in persons with atherosclerosis or hypertension. A recording of systolic murmurs of aortic stenosis is available at http://youtu.be/Gbk2465HO98.

Primary care physicians should consider aortic stenosis in adults who present with any of the cardinal symptoms accompanied by a systolic murmur. In addition, asymptomatic patients who have holosystolic and late systolic murmurs, grade 3 or louder mid-peaking systolic murmurs, or murmurs that radiate to the neck should be evaluated for aortic stenosis. A low-intensity murmur alone does not exclude aortic stenosis, especially as LV systolic function deteriorates. The only physical examination finding that can exclude severe aortic stenosis is a normally split second heart sound.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

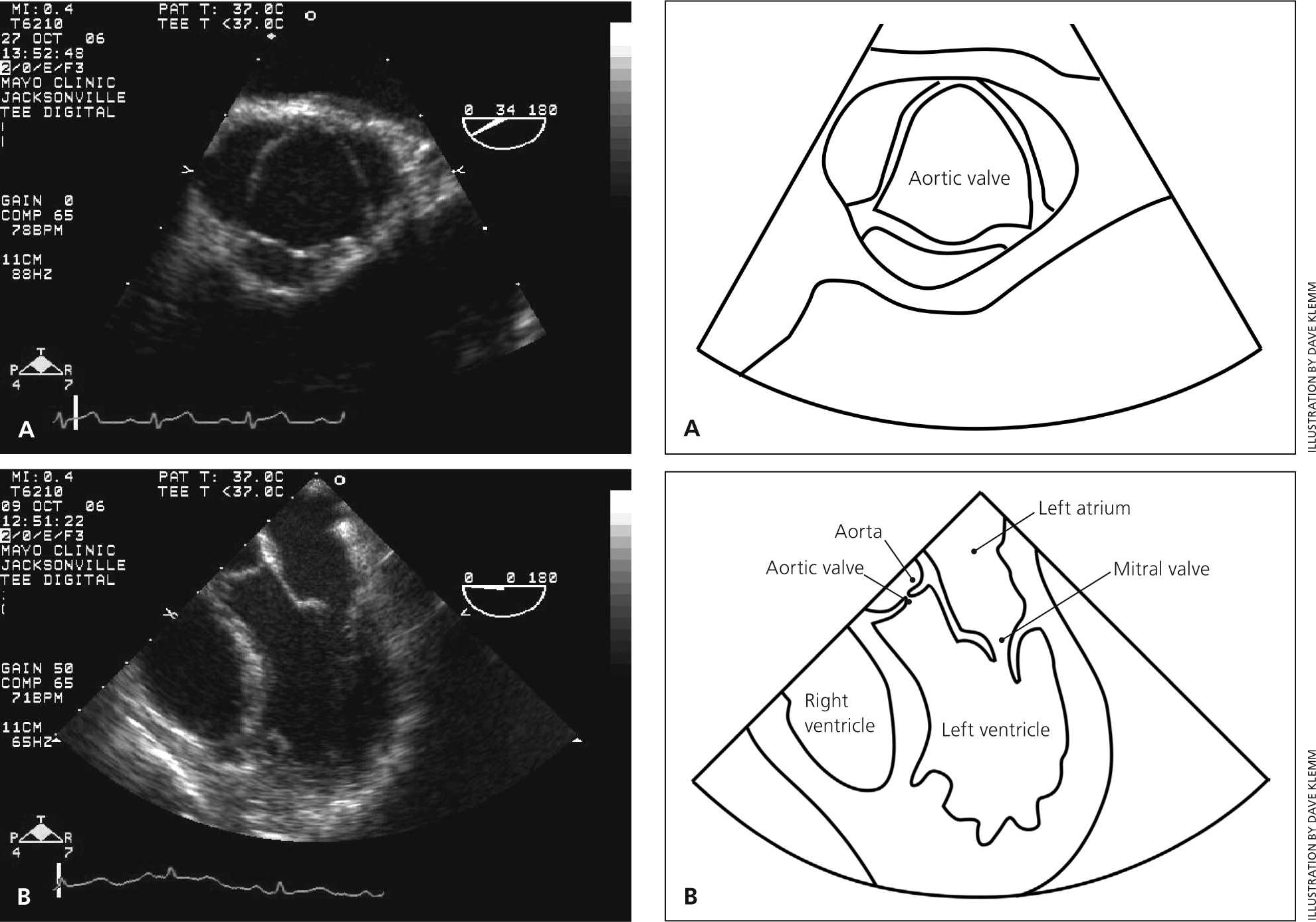

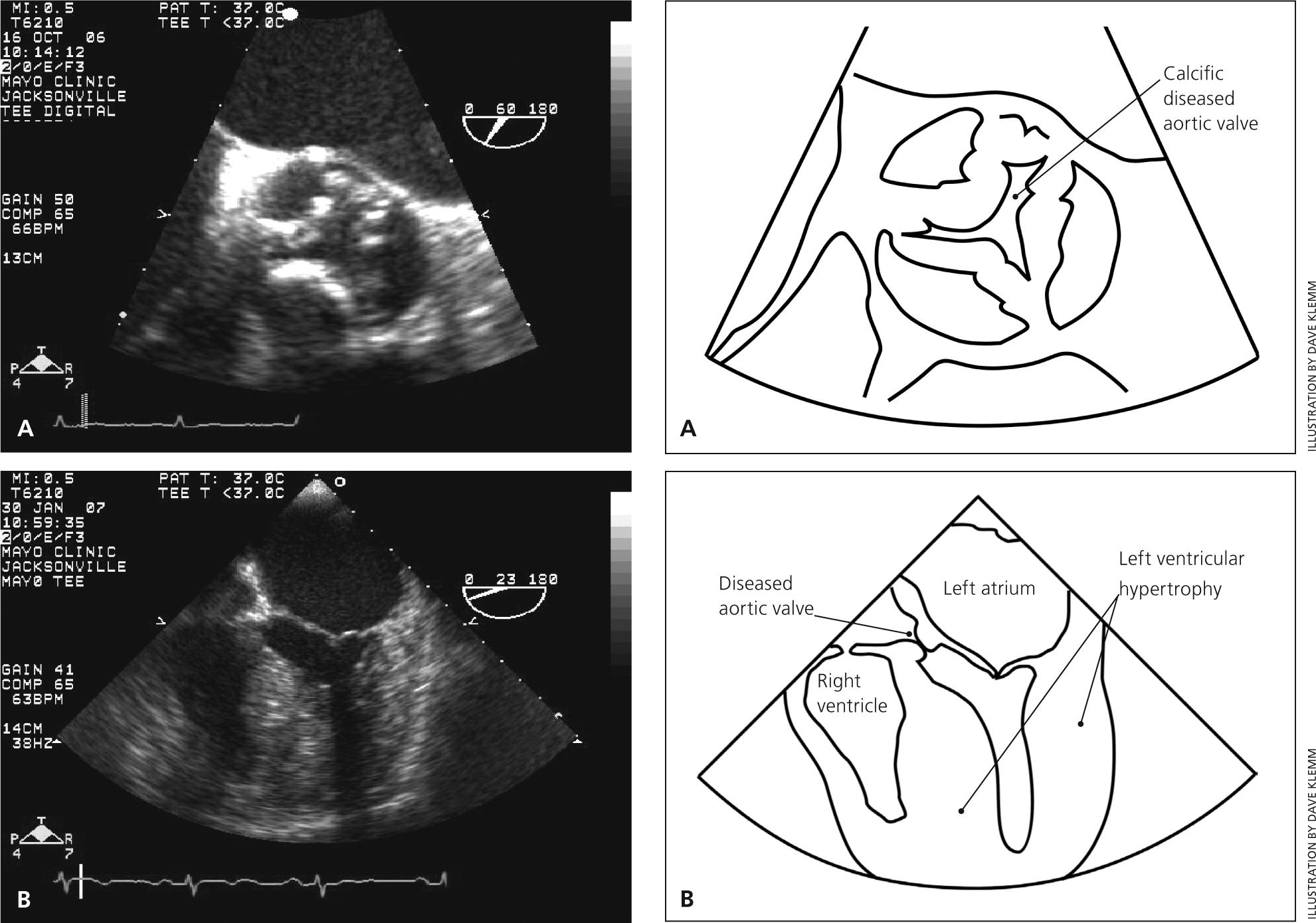

Echocardiography is indicated in patients with a loud unexplained systolic murmur, a single second heart sound, a history of a bicuspid aortic valve, or symptoms that may be caused by aortic stenosis.18–20 Transthoracic echocardiography, the recommended initial test for patients with suspected aortic stenosis, allows reliable identification of the number of valve leaflets and assessment of valve motion, leaflet calcification, and LV function.20 The primary indices of stenosis severity are maximum transaortic velocity and the Doppler-derived mean pressure gradient (Table 1).20 Patients typically remain asymptomatic until maximum transvalvular velocity is more than four times the normal velocity or at least 4.0 m per second.21–23 However, stenosis severity may be more difficult to assess in some patients who have only a moderately elevated transaortic velocity (3.0 to 4.0 m per second) but an aortic valve area less than 1.0 cm2. If concurrent LV dysfunction is detected (ejection fraction [EF] less than 50%), these patients may have clinically significant “low-flow” aortic stenosis.

| Classification | Transaortic velocity (m per second) | Mean pressure gradient (mm Hg) | Aortic valve area (cm2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | < 2.0 | < 10 | 3.0 to 4.0 |

| Mild | 2.0 to 2.9 | 10 to 19 | 1.5 to 2.9 |

| Moderate | 3.0 to 3.9 | 20 to 39 | 1.0 to 1.4 |

| Severe | ≥ 4.0 | ≥ 40 | < 1.0 |

Referral and Treatment

AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

Classic symptoms of aortic stenosis accompanied by echocardiographic findings consistent with severe stenosis should prompt cardiology consultation.20,22,24,25 Although outcomes in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis are similar to those in age-matched control patients, survival is extremely poor once even subtle symptoms are present. Two-year mortality rates of 50% to 68%—most often secondary to congestive heart failure—have been reported in symptomatic older patients who did not undergo surgical treatment.26–28

Aortic valve replacement is the only effective treatment for symptomatic, hemodynamically severe aortic stenosis. Surgical replacement leads to significant improvement in survival, usually accompanied by symptom improvement.28–32 The 10-year survival rate in Medicare-aged patients after aortic valve replacement is almost identical to that in age- and sex-matched persons who do not have aortic stenosis.33 Although no randomized trials have compared aortic valve replacement with medical management in persons at low surgical risk, observational studies showing a more than fourfold difference in survival between surgically and medically treated patients support the well-accepted recommendation that valve replacement be performed promptly in symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis.

Cardiology referral is also appropriate when a symptomatic patient is found to have moderate stenosis because it may lead to the identification of low-flow, low-gradient severe aortic stenosis despite a normal EF (due to a small stroke volume in a patient with a small ventricular cavity). This scenario is more common in older women with hypertension. Alternatively, if the EF is less than 50%, dobutamine stress echocardiography may reveal severe aortic stenosis or prompt evaluation for other causes of LV dysfunction.

Aortic valve replacement is also recommended for asymptomatic patients with severe stenosis accompanied by LV systolic dysfunction (EF less than 50%). When severe stenosis is found to be the primary pathology in this setting, aortic valve replacement is a lifesaving therapy and improves LV function.34,35 Aortic valve replacement is also indicated in asymptomatic patients with severe or even moderate stenosis who are undergoing cardiac surgery for other indications; this avoids the need for repeat surgery once the valve disease inevitably progresses.

WATCHFUL WAITING

Watchful waiting is recommended for most asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis, including those with severe disease.20,25,34,36 Survival rates are comparable to those in patients without aortic stenosis, and the mortality risk in patients undergoing valve replacement outweighs the risk of sudden death in asymptomatic patients with aortic stenosis.

Attempts have been made to identify patients who are more likely to have poor outcomes without early aortic valve replacement. Patients with severe stenosis (transaortic velocity of at least 5.0 m per second) or a rapid increase in transaortic velocity over time (0.3 m per second or more per year) have a high likelihood of becoming symptomatic and of needing aortic valve replacement within the next one to two years. Valve replacement may be considered in these patients if they have a low surgical risk. High-risk patients, including those who do not live near a medical care facility, may need closer monitoring or consideration of potential benefits vs. risks of early valve replacement.25,34,36

It is important to distinguish patients who are truly asymptomatic from those whose routine activity level has subtly decreased to below their symptom threshold. This is especially important in older patients, who may attribute their symptoms to normal aging or concurrent illness. In patients whose symptom status is unclear, cautious exercise stress testing can objectively assess exercise tolerance or detect an abnormal blood pressure response (hypotension with exertion), possibly leading to a recommendation for aortic valve replacement.37,38

SURGICAL VS. TRANSCATHETER AORTIC VALVE REPLACEMENT

Surgical aortic valve replacement is the standard of care in patients with low or intermediate surgical risk.20 Overall 30-day surgical mortality for isolated valve replacement is 3% and approximately 4.5% for valve replacement with coronary artery bypass grafting.39 Transcatheter aortic valve replacement is recommended for patients who have an indication for valve replacement but are at prohibitive surgical risk. Transcatheter valve replacement is also a reasonable alternative to surgical valve replacement in high-risk patients. Surgical risk should be assessed by a multidisciplinary team composed at minimum of a clinical cardiologist and a cardiac surgeon, and usually including subspecialists in interventional cardiology, cardiovascular imaging, anesthesiology, and heart failure management.

Medical Management

In asymptomatic patients, serial Doppler echocardiography should be performed every six to 12 months in those with severe aortic stenosis, every one to two years in those with moderate stenosis, and every three to five years in those with mild stenosis.20 Transthoracic echocardiography should also be performed when any changes are detected on physical examination. Most importantly, patients should be educated about symptoms and the importance of promptly reporting them to their physician.

No medical treatments delay the progression of aortic valve disease or improve survival. However, many patients with asymptomatic stenosis have concurrent cardiac conditions, including coronary artery disease, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation; these conditions should be controlled while keeping in mind their potential effects on progressive aortic stenosis.20,34

CARDIOVACULAR RISK REDUCTION

In addition to discussing the benefits and risks of statin therapy and aspirin prophylaxis, the physician should determine a patient's 10-year cardiovascular risk according to current guidelines. The overall risk of cardiovascular events increases 1.5- to twofold in the presence of aortic valve calcification, even in the absence of valvular stenosis.40,41 Other risk-reduction measures should include discontinuation of tobacco use and participation in regular exercise if exertional symptoms are not present. Patients with mild stenosis should not be restricted from physical activity. Asymptomatic patients with moderate to severe stenosis should avoid competitive or vigorous activities that involve high dynamic and static muscular demands, although other forms of exercise are safe.20,42

HYPERTENSION

Approximately 40% of patients with aortic stenosis also have hypertension,34,43 which results in elevated LV after-load due to the “double load” created by stenosis plus increased vascular resistance. Treatment of hypertension is recommended in patients with asymptomatic aortic stenosis.44–46 However, these patients can be particularly sensitive to the manipulation of preload, contractility, or systemic vasomotor tone.47

Antihypertensive agents should be initiated at low doses and gradually titrated. In addition to being well tolerated, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors improve hemodynamic parameters, augment effort tolerance, and reduce dyspnea in symptomatic patients with severe aortic stenosis.46,48 Second-generation dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (e.g., amlodipine [Norvasc], felodipine) do not seem to depress LV function as older calcium channel blockers do, and are safe to use in patients with aortic stenosis. Diuretics should be started at low doses because of the potential for reducing LV diastolic filling, which may reduce cardiac output. Use of peripheral alpha blockers may lead to hypotension or syncope and should be avoided.

ATRIAL FIBRILLATION

Atrial fibrillation occurs in 5% of patients with aortic stenosis. New-onset atrial fibrillation may precipitate heart failure in a previously asymptomatic patient with significant aortic stenosis. Heart rate control is important to allow time for optimal diastolic filling. However, physicians should be aware that beta blockers and rate-slowing calcium channel blockers may depress LV systolic function in patients with aortic stenosis.

ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS

Antimicrobial prophylaxis for bacterial endocarditis is recommended in patients with a history of endocarditis and in those with prosthetic heart valves (mechanical valves, bioprostheses, and homografts), but not in those with aortic stenosis or other acquired valve diseases.49

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Evidence Reports, National Guideline Clearinghouse, and PubMed. Key words included aortic valve stenosis, aortic stenosis guidelines, heart murmur, statin, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and bacterial endocarditis prophylaxis. Search dates: June 20, 2014; October 20, 2014; and November 16, 2015.

This review updates a previous article on this topic by Grimard and Larson.17