Am Fam Physician. 2017;96(12):784-789

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Palpitations are a common problem in the ambulatory primary care setting, and cardiac causes are the most concerning etiology. Psychiatric illness, adverse effects of prescription and over-the-counter medications, and substance use should also be considered. Distinguishing cardiac from noncardiac causes is important because of the risk of sudden death in those with an underlying cardiac etiology. A thorough history and physical examination, followed by targeted diagnostic testing, can distinguish cardiac conditions from other causes of palpitations. Persons with a history of cardiovascular disease, palpitations at work, or palpitations that affect sleep have an increased risk of a cardiac cause. A history of cardiac symptoms, a family history concerning for cardiac dysrhythmias, or abnormal physical examination or electrocardiography findings should prompt a more in-depth evaluation for heart disease. Ischemic symptoms may signal coronary heart disease and associated ventricular premature contractions that may warrant exercise stress testing. Exertional symptoms accompanied by elevated jugular venous pressure, rales, or lower extremity edema should raise concern for heart failure; imaging may be required to assess for functional and structural heart disease.

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: PALPITATIONS

Supraventricular premature complexes, which can be distinguished from ventricular premature contractions when nonsinus atrial depolarizations are followed by narrow QRS complexes, are associated with significant increases in atrial fibrillation, stroke, cardiovascular disease, and death, even if asymptomatic.

In addition to cocaine, methamphetamine, and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or Ecstasy), marijuana use can cause arrhythmias and should be assessed in patients presenting with palpitations.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| All patients presenting with palpitations should be evaluated for an ischemic cause. | C | 3, 5, 16 |

| Nonspecific ST-segment and T-wave changes in symptomatic patients should not be considered normal and should prompt further evaluation for a cardiac cause. | C | 25 |

| Patients who have syncope associated with palpitations should undergo tilt-table testing. | C | 15, 17, 19 |

| Transthoracic echocardiography should be considered to evaluate for heart failure or structural heart disease in patients with palpitations accompanied by elevated jugular venous pressure, rales, or lower extremity edema. | C | 3 |

Pathophysiology

Ordinary cardiac transmission involves the spontaneous discharge of an electrical impulse at the sinoatrial node. The impulse is then propagated down the wall of the right atrium to the atrioventricular node, then disseminated via the His-Purkinje system to depolarize the ventricles. Disturbance of the electrical impulse anywhere along these pathways may produce an arrhythmia. Noncardiac factors (e.g., thyroid disease, pheochromocytoma, psychiatric disorders, medications) may affect this process. Hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism can affect cardiac function by impairing cardiac pliability and oxygen demand, resulting in arrhythmia.9,10 Panic attacks, anxiety, and somatization disorder can cause palpitations due to autonomic activation.11 Pheochromocytoma can also lead to catecholamine excess.12

Differential Diagnosis

Although the most pressing concern during the evaluation of a patient with palpitations is to uncover any underlying cardiac cause, noncardiac causes may also contribute and are potentially treatable (Table 1).2,4,5,7,9,10,13–19 Determining the cause is important to assess risk. Palpitations account for 16% of visits to generalist physicians and are the second leading cause of visits to cardiologists.16 Table 2 lists the relative frequencies of causes of palpitations.11,16

| Cardiac | Noncardiac |

|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation/flutter | Alcohol |

| Atrial myxoma | Anemia |

| Atrial premature contractions | Anxiety/stress |

| Atrioventricular reentry | Beta-blocker withdrawal |

| Atrioventricular tachycardia | Caffeine |

| Autonomic dysfunction | Cocaine |

| Cardiomyopathy | Exercise |

| Long QT syndrome | Fever |

| Multifocal atrial tachycardia | Medications |

| Sick sinus syndrome | Nicotine |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | Paget disease of bone |

| Valvular heart disease | Pheochromocytoma |

| Ventricular premature contractions | Pregnancy |

| Ventricular tachycardia | Thyroid dysfunction |

| Etiology | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Psychosomatic | 31 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 16 |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 10 |

| Medication/illicit substances | 6 |

| Systemic disease | 4 |

| Structural heart disease | 3 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 2 |

Clinical Diagnosis

HISTORY

All patients presenting with palpitations should be evaluated for an ischemic cause.3,5,7,8,16 Many cardiac causes, both arrhythmic and structural, have a genetic component, underscoring the value of a thorough family history focused on early cardiac death and inherited cardiac conditions. Physicians should ask whether the palpitations are associated with activity. Palpitations with cardiac causes may occur at rest (e.g., vagal nerve–mediated ventricular premature contractions [VPCs]) or with exertion (e.g., dehydration exacerbating mitral valve prolapse cardiomyopathy, exertional syncope), which suggests more worrisome etiologies.

A systematic review concluded that a history of cardiovascular disease, palpitations occurring at work, or palpitations that affect sleep have an increased risk of a cardiac cause (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 2.0 to 2.3).3 Symptoms of a regular, rapid, pounding sensation in the neck, although rare, are strongly associated with atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia (LR+ = 177); this diagnosis is also supported by visible neck pulsations (LR+ = 2.7).3

Position. Patients who have palpitations due to atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia may find that their symptoms are triggered by standing up after bending over. They may also notice symptoms while lying in bed. This most often represents supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) or VPCs.20

Syncope and Presyncope. Loss of consciousness is an important factor when evaluating a patient with palpitations. Syncope should raise concern for arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia, or structural heart disease (e.g., hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) with outflow tract obstruction impairing cardiac output to the extent that cerebral blood flow is impaired. Although syncope or presyncope can occur with vasovagal syncope, its occurrence during exertion in an athlete is of particular concern because of the increased risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmia that may result in sudden cardiac death. In young athletes, the incidence of sudden cardiac death is estimated to be one to three cases per 100,000 person-years.20 Etiologies include cardiomyopathies, congenital coronary anomalies, and ion channelopathies.20

Medication and Substance Use. A history of all prescription and over-the-counter medications should be obtained. Medications used to treat attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and rescue inhalers for asthma may cause palpitations. Over-the-counter nasal decongestants, herbal preparations, and supplements such as omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, coenzyme Q10, and carnitine may also cause palpitations.21

Patients should be evaluated for the use of illicit substances such as cocaine and methamphetamine. Signs and symptoms such as pupillary dilation, sweating, aberrant behavior, and dry mouth should be noted. The use of cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA or Ecstasy), and methamphetamine should be assessed in patients presenting with palpitations. Marijuana use can also cause arrhythmias.13 Other substances that may cause palpitations include performance-enhancing drugs such as anabolic steroids.13,22 Nicotine, caffeine, and alcohol are commonly used legal substances that may induce palpitations.

Psychiatric History. Anxiety is the most common noncardiac etiology of palpitations.1–3 Patients whose symptoms are more likely to be of a psychiatric nature are significantly younger, may have a disability, express hypochondria-type behavior, and may have a somatization disorder.14 A history of panic disorder (negative likelihood ratio [LR–] = 0.26) or palpitations lasting less than five minutes (LR– = 0.38) make a cardiac etiology less likely.3 However, physicians should not presume that a known behavioral issue is the etiology of palpitations in patients with psychiatric symptoms, because a non-psychiatric source exists in up to 13% of such patients.1,23

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The pattern of arrhythmia as heard on auscultation can be helpful in determining the cause.3 An irregular pulse with no repeating pattern suggests atrial fibrillation. A cannon A wave noted when observing for jugular venous pulse often occurs in ventricular tachycardia. Mitral valve prolapse is the most common structural heart disease resulting in palpitations.14 This may be suggested by the presence of a holosystolic murmur or a midsystolic click. However, if the murmur is particularly harsh, cardiomyopathy should be considered as the underlying cause.

Other cardiac valvular lesions, particularly congenital lesions, should be considered in younger patients with palpitations. This includes pulmonary stenosis, atrial septal defects, and bicuspid aortic valve.

Diagnostic Testing

Figure 1 provides an overview of the diagnostic evaluation of patients with palpitations.7,14,15,17,24 Baseline laboratory testing should include a complete blood count; blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, and electrolyte levels; and thyroid function tests to exclude anemia, renal disease, and electrolyte or thyroid disorders.15

Standard 12-lead electrocardiography (ECG) is essential in patients presenting with palpitations.4,5,7 A prolonged QT interval suggests polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, whereas a short PR interval or delta wave (i.e., a slurred upstroke of the QRS complex with a shortened PR interval) suggests a reentrant tachycardia via an accessory pathway.24 Nonspecific ST-segment changes and T-wave abnormalities may be important clues to the presence of myocardial disease. Although often considered normal variants, these changes are not: in a study of 3,224 patients with nonspecific ST-segment changes (mean age = 72 years), there was a significant increase in arrhythmogenic causes of death (32.3% vs. 15.4%; P = .02).25 Normal resting ECG findings do not eliminate a cardiac etiology.4 If the index of suspicion for a cardiac cause remains high, ambulatory ECG monitoring is warranted. This is most helpful when the patient experiences specific triggers or if the symptoms tend to occur daily, in which case a 24-hour Holter monitor can be ordered.24,26

If symptoms are less frequent, an event monitor can be worn for longer periods (typically 30 days). Event monitors store data after they have been activated during a symptomatic episode or if an abnormal heart rhythm is noted. Newer implantable loop monitors run continuously and can provide real-time data.3 Easily placed loop monitors may be a cost-effective approach in patients with infrequent episodes of palpitations accompanied by syncope concerning for an arrhythmic etiology.27

Patients with exertional symptoms should be evaluated with standard exercise stress testing because they are at higher risk of morbidity and mortality.2,3 In patients with syncope or near-syncope and abnormal ECG findings, Holter and/or event monitoring and tilt-table testing may be warranted.3,15,17,19,24 Transthoracic echocardiography is helpful in evaluating patients for structural heart disease and should be performed when the initial history, physical examination, and ECG findings are unremarkable, or in patients with a history of cardiac disease or more complex signs and symptoms (e.g., dyspnea, rales, elevated jugular venous pressure, orthopnea, lower extremity edema).3

Treatment

Although an extensive discussion of the treatment of atrial fibrillation is beyond the scope of this article, the following sections briefly present the management of common arrhythmic causes of palpitations in patients in the primary care setting.

VENTRICULAR AND ATRIAL PREMATURE CONTRACTIONS

VPCs are common in patients with underlying cardiac disease as well as in those who are otherwise healthy.28 Isolated, monomorphic VPCs are more likely to be benign compared with frequent, consecutive, or multiform ventricular ectopy.4 When evaluating a patient with VPCs, the first step is to determine whether there is underlying structural heart disease (most often by echocardiography) because mortality is increased in this group.17 Patients in whom at least 25% of heartbeats are VPCs have an increased risk of VPC-induced cardiomyopathy. Patients with a decreased ejection fraction have VPCs more often than those with normal left ventricular function (33% vs. 13%; P < .0001).29 The prognosis of VPC-induced cardiomyopathy is good in patients without other cardiac problems.30 As with VPCs, atrial premature contractions are common and can occur in patients with or without heart disease.31 Atrial premature contractions in a person with a family history of cardiomyopathy should prompt a more detailed cardiac evaluation.

SUPRAVENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA

SVT may manifest as a narrow complex (QRS complex less than 120 msec) or wide complex (QRS complex greater than or equal to 120 msec) tachycardia.5,6 It most often presents with recurrent, paroxysmal episodes that may increase in frequency and severity.32 In the general population, the incidence of paroxysmal SVT is 35 per 100,000 person-years (95% confidence interval, 23 to 47).18

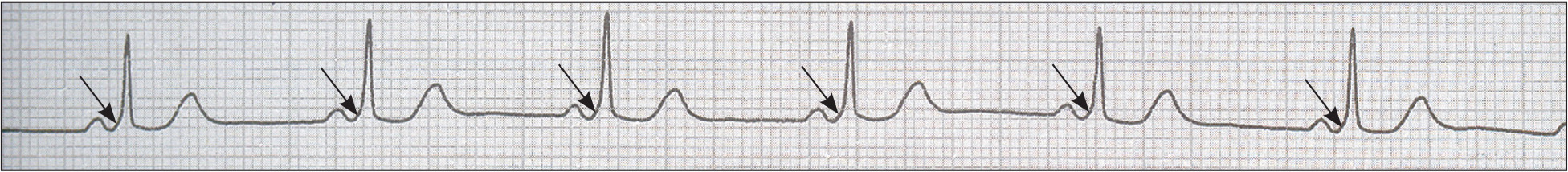

SVT is not typically associated with structural heart disease, but it may accompany hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the Ebstein anomaly. Wide complex tachycardia should be presumed to be ventricular tachycardia when the diagnosis is unclear—particularly if it occurs in the presence of structural heart disease—and requires further evaluation.5 The presence of a delta wave (Figure 22) indicates an accessory pathway,6 although accessory pathway conduction may be concealed.

In patients with narrow complex SVT, infrequent and self-terminating episodes without syncope may not require further intervention.32 Persistent or hemodynamically significant SVT can be aborted with intravenous adenosine; calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, or other antiarrhythmics can also be used.8 In refractory cases, synchronized cardioversion can be considered for short-term treatment, or radiofrequency catheter ablation for longer-term treatment.27 Patients with SVT or syncope associated with palpitations should be referred to a cardiologist.

Supraventricular premature complexes can be distinguished from VPCs when nonsinus atrial depolarizations are followed by narrow QRS complexes. Even when asymptomatic, they are associated with a significant increase in rates of stroke, cardiovascular disease, and death.33 Supraventricular complexes are not benign and are associated with a higher risk of developing atrial fibrillation. They are also associated with a higher risk of all-cause mortality and stroke, based on a 10-year prospective observational study of more than 63,000 Japanese adults 40 to 79 years of age.33 Beyond risk factor modification, however, no specific treatment is recommended for asymptomatic patients with atrial premature contractions who have no other apparent structural, functional, or electrical abnormality.

VENTRICULAR TACHYCARDIA AND LONG QT SYNDROME

Ventricular tachycardia is defined as three or more consecutive heartbeats initiating in the ventricle at a rate greater than 100 beats per minute. It can be sustained (30 seconds or more) or nonsustained (less than 30 seconds), as well as monomorphic (one QRS morphology) or polymorphic (more than one QRS morphology). The risk of sudden cardiac death in patients with ventricular tachycardia is associated with the number of beats during an arrhythmic episode. Patients with three or fewer beats do not have an increased risk of sudden death; however, the risk increases in persons with tachycardia lasting four to seven beats (2.9%; adjusted hazard ratio = 2.3; P < .001) or more (4.3%; adjusted hazard ratio = 2.8; P = .001).34

Long QT syndrome is characterized by a prolonged QT interval on ECG (more than 460 msec for women and more than 440 msec for men).8 It may be life-threatening and should trigger immediate intervention and consultation with a cardiologist. It is important to note that use of medications such as beta blockers is contraindicated in these patients because they may result in syncope and increase the risk of death. In one study of persons included in the International Long QT Syndrome Registry, those with a long QT interval who were subsequently prescribed a beta blocker had a 3.6-fold increase in the risk of severe arrhythmic events (P < .001).19

Data Sources: American Family Physician provided an initial literature search from Essential Evidence Plus and PubMed. This was supplemented by a search of the Cochrane database and the National Guideline Clearinghouse. Specific journals searched include Journal of the American Medical Association, New England Journal of Medicine, Circulation, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, American Journal of Cardiology, American Family Physician, European Heart Journal, and Archives of Internal Medicine. Search dates: January 10 to July 10, 2016.