Compensation may not be simple, but it can be (mostly) fair — even motivating. Here's the plan one family physician devised for his group.

Fam Pract Manag. 1998;5(9):50-57

Years ago, when HMOs and managed care contracts were just beginning to surface, I was tasked (and tasked myself) with developing a physician compensation formula for our six-physician family practice group. What our group needed was a model that addressed the pressures of managed care, motivated us to be a cost-efficient and productive team, and felt fair. Initially I thought this formula would be easy to construct, ratify and implement, but I soon found out how wrong and naive this thought was. My first clue came when I stumbled upon a compensation model proposed by Gaynor and Gertler in The RAND Journal of Economics,1 which read:

It is an impressive formula, and, if you're well versed in calculus and econometrics, I'm sure it is meaningful. But it doesn't have much to say to the rest of us, practical and practicing docs wrestling with the very practical problem of dividing income.

Now, several years since I first embarked on this project, I can report that, while the easy and entirely just formula does not exist in the literature or in practice, I have identified what I think is a reasonable and rational compensation formula for our group. My colleagues have given this formula their blessing, ratifying it just a few months ago, and we are working now to have the formula fully in place for the new year. I know that no two groups resemble one another enough that the same exact formula could work for both, but I share this model and our group's experience with the hope that other primary care physicians can adapt it for their own groups — or at least use our approach to arrive at their own formula.

First, why bother?

It's been said that money problems are like medical problems: They can fester until they become difficult to cure.2 In fact, disputes over money are a common reason for failures in medical groups, and the advent of managed care has only amplified the debate over the division of income. As practices make the transition from fee for service to capitation, many are finding that their physician compensation systems are no longer relevant and no longer seem fair. Many physicians feel they are working harder and longer while being paid less. And many more physicians, myself included, are seeing little incentive to continue working so hard.

Two additional factors were prompting our group to revisit our compensation formula. First, we were getting more heavily involved in managed care, with over two-thirds of our patients being part of managed care plans. Second, our old compensation system of equal shares and straight salary was indebting our group; we were essentially overpaying ourselves in relationship to our actual revenues.

In today's environment, an effective compensation formula should have these five qualities:

First, it should be fair economically — not necessarily producing equal shares, but fair.

Second, it should be comprehensible, especially to the physicians being compensated.

Third, it should not be excessively difficult for management to monitor and administer, and it should be flexible enough to allow for possible future modification.

Fourth, it should be consistent with the philosophy and mission statement of the practice.

And finally, it should stimulate its physicians to be effective, with definable financial rewards for behavior and activity the practice needs and wishes to encourage.

The model of choice

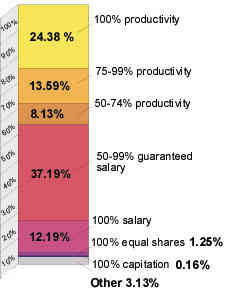

With the above qualities in mind, the first basic decision for any group is what type of compensation model to follow. These models range from equal shares to straight salary to fully productivity-based, and each has its own pros and cons (see "Six compensation models"). The model our group has adopted is one that provides a high guaranteed salary plus bonus/incentive pay. According to data from the Medical Group Management Association, 37 percent of primary care groups use this model (see “How your peers are paid”). The assets of this model are several:

It decreases intragroup competition, and thus promotes a team environment within the practice.

It allows for a known base income that can be set to be generous enough to support a reasonable middle-class lifestyle for the physicians without making the group as a whole go into debt.

It incentivizes and rewards behaviors and efforts the group wishes to promote.

It is flexible in the weight it assigns to nonsalary pay determinants, so the formula can be modified as needed to reflect changes in income streams, different values assigned to an activity, increasing sophistication of accounting methods, etc.

Six compensation models

There are essentially six different models of physician compensation, each with its own pros and cons:

Equal sharing

This is the simplest arrangement administratively. It is based on an economic model that presumes all participants are equally skilled and motivated and are performing at the same level. This model discourages overutilization but offers no incentive for productivity, however measured. Additionally, it penalizes high producers and allows low producers to “coast.”

Productivity

The obvious advantage of this model is that it encourages extra professional effort and seems “just” in a capitalistic economic system. The disadvantages are that it feeds intragroup competition, requires substantial accounting management to assign overhead burden fairly, encourages overutilization and can even discourage citizenship, such as practice governance and management, teaching and other activities not connected with patient visits.

Salary

Straight salary is easy to administer but can disincentivize entrepreneurship and may indebt the corporation if actual revenue is less than what is being paid out.

Salary plus bonus

A significant advantage to this method is that it offers security. It also enables physicians to increase their income through performance. On the down side, this method may cause minimum work standards to become de facto norms. This method also places a large component of income at risk, depends on subjective measurements in apportioning that at-risk portion, and can be complex to design and administer.

Productivity plus capitation mix

This method recognizes the different revenue streams coming into a practice, rewards physician activity appropriately per stream and encourages efficiency as physicians move into pure capitation. However, it is complicated to administer, and the two-tiered practice style it encourages can create a dichotomy within the practice, with differential treatment levels based on patients' payment streams.

Capitation

Capitation rewards certain physician behavior, such as appropriate utilization, and encourages physicians to have an interest in appropriate and efficient provision of care. The danger is always that it may encourage under-utilization, and it requires complex tracking of data.

A base salary

The next major decision, then, is establishing what that base salary will be. Base salaries vary widely, ranging from 20 percent to 99 percent, depending on the group's objectives and needs. For our group, the base salary needed to be livable for the physicians, but it also needed to be affordable for our practice and fit comfortably within our budget. Additionally, we wanted a significant portion of the compensation to be tied to incentives so that it would truly motivate us to be more efficient and productive (a little bit of greed can go a long way toward making a group stronger economically). What I recommended for our group was that the base salary be set at 75 percent of the group's previous year's mean W-2 earnings.

While it is a salary, there are some strings attached. To be eligible for the full salary, a physician in our group must have worked 90 percent of the mean number of days worked per year for physicians in the office. Also, a physician must have had 90 percent of the mean number of office visits (regardless of complexity) and must also have taken his or her fair share of call hits.

My thought was that, if a physician was not able to meet the group's targets, his or her salary would receive a deduction. After all, in a doctor's absence, fixed overhead continues and others' workloads increase, both of which must be compensated for. For example, say the base salary is $75,000, the mean days worked in the year is 200 full days, and the mean patient load is 5,000 (or 25 patients per day). Let's say that Dr. X works 175 days, or 5 days less than 90 percent of the mean, but sees 5,200 patients. He is penalized 5/200 of $75,000, or $1,875, for missing those five days.

Meanwhile, Dr. Y also works 175 days and sees only 4,300 patients (200 short of 90 percent of the mean). In a case like this, where both numbers are below the target, the physician would be penalized the greater dollar amount, not the sum of the two shortfalls. Dr. Y, then, would be penalized 200/5,000 of $75,000, or $3,000, at the end of the fiscal year.

The advantages of this type of calculation are, first of all, ease of administration; all we need are a few easily retrievable and easily tabulated numbers (days worked and office visits per year). Additionally, allowing physicians the 10 percent leeway seems fair; physicians aren't penalized if they don't fall exactly in line with the mean. While outcome is pegged to group norms, it should not engender intense in-group competition or gaming the system.

For subsequent years, the salary base will be recalculated using the physicians' mean practice income for the previous year. One potential downside: Using a system like this in a practice whose fiscal year is discordant with the IRS fiscal year may require a midyear adjustment.

How your peers are paid

Physician compensation methods

Source: Medical Group Management Association. Physician Compensation and Production Survey: 1997 Report Based on 1996 Data.

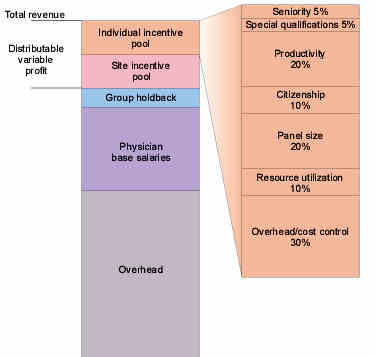

A group war chest

The next decision (and probably the simplest) is whether to hold back revenue in and for the group. This money would be set aside for substantial future expenses, shortfalls, business opportunities, etc. Experts often recommend a 2 percent to 5 percent “war chest”; our group decided to hold back 5 percent of our group income after overhead and physician salaries. What remains, then, is a “distributable variable profit,” which will be used as incentives.

Two incentive pools

Because the distributable variable profit reflects both group and individual effort toward productivity, efficiency and profitability, it seems fair to divide the incentive money equally into two portions: a site incentive pool and an individual incentive pool (see “The author's proposed distribution of revenue”). The site incentive pool is to be divided equally among all the principals of the group (that is, the owner/partner doctors), as this reflects group effort and efficiency. Distribution and reporting of this pool should be done quarterly, to effectively stimulate growth and change.

The author's proposed distribution of revenue

Probably the hardest decision of all is how to distribute the individual incentive pool, which is not apportioned in equal shares. The issue is difficult because you are trying to incentivize and reward behaviors that are both quantitative and qualitative. These behaviors are hard to agree upon and even harder to measure. There is little consensus in the literature on what factors to use or what weights to assign to them. Ultimately, groups must select the items they hold most important and can measure, and they must assign relative economic weight to each. These items should perhaps be revisited and reratified every year, just as a budget is.

Factors that might be considered in the individual incentive pool include both positive and negative items. First, the positive elements:

Seniority: years of service,

Quality: based on data such as health maintenance parameters (i.e., the percentage of charts reviewed that show appropriate attention to vaccination, screening, sigmoidoscopy, Pap smears, etc.),

Patient satisfaction: based on patient surveys,

Administration: group leadership and management of the practice,

Productivity: measured in terms of the number of patient encounters (including billed hospital visits, home visits, nursing home visits, etc.), RVUs or some other unit,

Citizenship: may include staff relations, hospital committee work, punctuality, behavior, governance and longevity,

Panel size or capitated lives: should correlate with total number of patients managed, as opposed to office visit productivity,

Special qualifications: may reward certain procedures, such as obstetrics.

The negative elements include these:

Resource utilization: ideally, this should address both over- and under-utilization.

Overhead/cost control: charging costs against individual physicians should help control costs; this category does not include fixed costs shared by the group as a whole (which might include rent, utilities, etc.); it involves only the percentage of overhead attributable to individual physicians: direct expenses (for instance, insurance costs) and indirect variable costs (for instance, supplies).

Dividing up the individual incentive pool

The next challenge is deciding how much of the individual incentive pool should go toward each element and how it should be distributed among the physicians. This is the framework our group has adopted:

Seniority, 5 percent. Each physician will receive a portion of this money based on his or her years in practice within the group.

Quality, 0 percent.

Patient satisfaction, 0 percent.

While we are deeply committed to quality care and patient satisfaction, we're not convinced we have the tools to appropriately measure and reward these areas. As our data become more meaningful, I can imagine quality being set at 5 percent; patient satisfaction at 10 percent.

Administration, 0 percent. Some groups allow anywhere from a 5 percent to even a 75 percent cash compensation for administration and leadership. We decided to reward extra administrative effort with a yearly stipend, which would be part of our fixed overhead costs.

Special qualifications, 5 percent.

For our group, this is mainly to reward those who do obstetrics, attend to nursing home patients or provide FAA physicals.

Productivity, 20 percent. Each physician receives his or her percentage of the productivity pot, based on his or her percentage of patient encounters within the group.

Citizenship, 10 percent. This is among the “softer” categories and is not exactly quantifiable, but our group believes in rewarding individual effort and good behavior.

Panel size or capitated lives, 20 percent. This is a simple calculation: Dr. X's panel size divided by the total number of assigned patients in the group equals his percentage of this pool.

Resource utilization, 10 percent. Each physician's portion of the utilization pool is based on the physician's own rates for referrals, X-rays, etc., divided by the group mean. Physicians receive an equal share of the utilization pool minus one percent for each percentage point above the mean or plus one percent for each percentage point below the mean.

Overhead/cost control, 30 percent. There are a number of ways to distribute the money allotted to this category, but the method I favor is similar to the above for utilization. First, calculate the individual overhead costs for each physician (i.e., direct expenses and indirect variable costs) and divide that by the group mean. Each physician then receives an equal share of the cost-control pot, minus one percent for each percentage point above the mean; plus one percent for each percentage point below the mean.

As I said earlier, we intend to review these percentages and categories periodically to make sure they continue to reflect the group's goals and needs. Having a formula with such flexibility is key in today's changing practice environment, and our group is optimistic that we have found a reasonable, workable structure that can motivate our physicians to work to full potential.