Negative feedback is never easy to give, but sandwiching criticism between layers of praise makes it more palatable and more effective.

Fam Pract Manag. 2002;9(10):43-46

Physicians are trained to treat patients, not to supervise staff. Yet, they are often expected to contribute to the selection, supervision and evaluation of residents or new physicians and may also be asked to play the leading role in running office practices. Most physicians take on supervisory roles with little or no past managerial experience and find the unfamiliar task challenging. While supervision does require a unique set of skills and procedural expertise, these are things you can learn. Setting expectations, providing formal evaluations and responding to performance deficiencies are the arms and legs of good supervision, but giving feedback is the backbone. Here's how to do it effectively.

The purpose of feedback

Perhaps the best way to think about feedback is in terms of behavior you want the employee to keep and behavior you want the employee to change. Remember that whether you are focusing on a strength or a weakness, you are simply providing your evaluation of your employee's performance, not his or her character.

Some supervisors avoid giving negative feedback because they fear that criticism will hurt their relationships with staff. However, when necessary criticism is withheld, supervisor-employee relationships remain superficial and lack the depth and resiliency needed to tackle sensitive issues. These supervisors are withdrawing from the authentic interactions that ultimately form the foundation of a trusting relationship. In addition, the supervisor's failure to confront performance problems may subsequently lead to aggressive behavior. In this case, unexpressed frustrations mount until a small error by the employee triggers an avalanche of pent-up criticism. Then, even if the supervisor's criticisms are accurate, the employee will be too overwhelmed to hear them. In the future, the employee will keep a safe distance from the supervisor and praise will be interpreted with suspicion.

Supervisors who speak up only to offer criticism also damage their relationships with employees. These supervisors may hold the assumption that excellence is expected, so praise is unnecessary. They fail to recognize that the main objective of praise is not to stroke the employee's ego but to encourage the employee to repeat desired behaviors. Changing and maintaining new behavior requires praise, because it helps the employee identify behavior that is worth repeating.

The feedback sandwich

If you're uncomfortable giving negative feedback, you may want to use a technique commonly referred to as “sandwiching”1 or a feedback sandwich. The basic recipe for a feedback sandwich consists of one specific criticism “sandwiched” between two specific praises (see “A feedback sandwich” for an example). This technique is fast, efficient and well suited to the time constraints of physician practice.

The feedback sandwich is particularly useful at the onset of any new supervisor-employee relationship, but it can benefit existing relationships as well. For a new employee, development of skills requires honing of behaviors, and praise and criticism are the best tools for the job. Once new skills are developed, the supervisor can direct less and delegate more. For a new supervisor, this technique can help him or her earn the trust of the employees by delivering artful feedback that enhances employee success.

Keep in mind that not every bit of praise or criticism needs to be sandwiched. When a supervisory relationship is healthy, there are times when praise and criticism can be given independently. Any technique that is applied too rigidly will eventually feel inauthentic.

The meat of the sandwich: Criticism

The main ingredient of a feedback sandwich is constructive criticism. When it is well timed, well targeted and well said, constructive criticism can help direct growth, motivate staff and offer relief from confusion.

A FEEDBACK SANDWICH

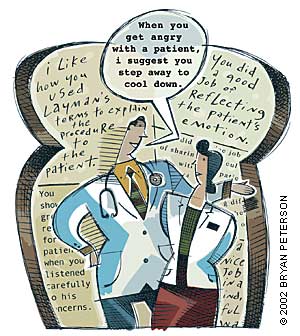

The following example shows how the “sandwiching” technique – combining specific praise and criticism – can be used to give an employee feedback.

This exchange focuses on the employee's patient-communication skills.

| Praise | “You did a good job of reflecting the patient's emotion. I saw her tear up when you said, ‘This diagnosis must feel devastating to you.’” |

| Criticism | “When you moved on to the exam, she was still crying. I suggest waiting 30 seconds more in silence. It is healing to have someone give you room to feel.” |

| Praise | “The patient shared her feelings with you, because you appeared relaxed and comfortable with her emotions.” |

Well-timed criticism occurs shortly after the error has occurred since the longer you wait to give feedback, the less effective it will be. It also takes into account the pressures of the moment and the employee's readiness to listen. While some employees may seem perpetually reticent to receive feedback, the vast majority are ready to learn, provided they are prepared to listen. You can help your employee prepare to listen by signaling that you are about to give feedback and by assessing whether the employee has the time to ingest the feedback you offer. Simply tell the employee that you'd like to discuss his or her performance, or use a nonverbal sign, such as a gesture, that invites the employee to take a seat.

KEY POINTS

Giving feedback is the backbone of good supervision.

Provide feedback on behavior you want the employee to keep and behavior you want the employee to change.

A feedback sandwich consists of criticism “sandwiched” between praise.

Some feedback is bite-sized and can be given in a relatively off-the-cuff manner. For example, no preparation is needed to say “That lesion requires another suture” or “Adjust the table.” Directions like these have a collaborative tone, are easily understood and do not address significant performance deficits. However, other types of feedback may be harder going down. For example, when a third-year resident cannot take an accurate blood pressure or an employee neglects to call a patient about an abnormal lab result, the feedback is more vital and the employee may feel more vulnerable. In situations like these, it may be helpful to go somewhere private and allow adequate time for proper digestion. Provide the employee with an opportunity to ask questions and react to what you say. Good supervisors are fair; they don't drop bombs and run off.

Well-targeted criticism is tailored to a particular employee performing a particular skill. Too much feedback at one time is not helpful. Ask yourself: “What is the most important teaching point right now?” I don't have to tell you about the gastrointestinal distress that results from overeating. If you want your feedback to be absorbed, you have to be selective.

Well-said criticism is direct, brief and, most of all, specific (e.g., “I like how you used layperson's terms to explain the procedure to the patient” instead of “You're good at that”). Avoid using general words such as “always” or “never,” and avoid personal-assault words such as “lazy” and “irresponsible.” Well-said criticism points the finger at the behavior rather than at the person.

The bread of the sandwich: Praise

In a feedback sandwich, the quality of the criticism and the praise are equally important. Don't use vague, insincere praise as a smoke screen to deliver bad news: “You're a really good employee, but we have to let you go. Don't worry, one of our competitors will snap you up in no time.” This is mixed or conflicting feedback, not a true feedback sandwich. Given that the employee is being fired, it is clear that performance deficits vastly outweigh strengths, so any praise at this time is disingenuous. It is also vague feedback. “Really good” does not tell the employee what behavior to repeat.

Praise, like criticism, should be well timed, well targeted and well said. Supervision offers many opportunities for genuine praise, especially when praise is understood as a way of reinforcing or shaping behavior. Helpful praise highlights desired behavior or behavior that is a step closer to desired behavior: “It was astute of you to assess cognitive functioning in this patient. You asked three good orientation questions. What are other questions you might ask to explore mental status?” In this case, the supervisor reinforces the decision to ask about orientation (praise) and then poses a question that will help the employee take the next developmental step.

The qualities of a chef

When making feedback sandwiches, supervisors can be either chefs or cooks, and assertive, skillful communication differentiates the two. Assertive supervisors (the chefs) express their thoughts and feelings directly, respect the person and address the behavior. Not all supervisors are assertive; some (the cooks) are passive or aggressive (see “Types of supervisors”). Here are some tips for delivering feedback sand wiches assertively:

Be prepared. Before giving feedback, take the time to collect your thoughts. It's easy to give aggressive feedback that's nonspecific and generalized, such as, “You never listen to patients.” It takes more effort to identify the problem behavior, describe it succinctly and offer a corrective solution assertively (e.g., “I noticed you interrupted Mr. Gold three times in the interview. It may help if you make a pact with yourself to repeat the patient's concerns before moving on to closed-ended questions”). Just as the employee must be prepared to receive feedback, you must be ready to offer it. The wrong time to give feedback is when you feel tired, frenetic, hungry or late. The right time to give feedback is when you're calm, focused and clear about the facts.

Be specific. The more specific you are in identifying “keep behaviors,” the more likely the employee will repeat them. Similarly, the more specific you are about behaviors you'd like to see the employee alter or stop, the more likely he or she will comply. Keep in mind that an employee can't change a behavior if he or she doesn't know what needs to be corrected, and if an employee feels personally judged, he or she is not likely to be motivated to change. Judge the person, and you risk the relationship. Judge the behavior, and you take the bite out of criticism.

| Assertive | Passive | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|

| Sees conflict as win-win | Avoids conflict | Sees conflict as win-lose |

| Expresses opinions directly | Relies on assumptions and nonverbal cues to convey opinions | Imposes opinions with fear tactics and ultimatums |

| Listens and considers others' thoughts and feelings | Submits to others' thoughts and feelings while minimizing their own | Downplays others' thoughts and feelings |

Suggest corrections. Don't leave the employee empty-handed. When giving change-oriented feedback, offer corrective, alternative behaviors to replace the problem behavior. If you think it is important for the employee to come up with a solution independently, spend time brainstorming ideas. If he or she is not likely to know the solution, be assertive and suggest one (e.g., “When you feel angry with a patient, I suggest you step away from the situation to cool down”).

Own your opinions. Assertive supervisors use “I” statements, owning the feedback they give. “I think or feel X” is more assertive than “People say X about you.” An example of an assertive statement might be: “When you raised your voice with Mrs. García, I noticed that she stepped back. If I were Mrs. García, I would shut down.”

Realize your boundaries. Have you ever had someone without authority or permission give you advice on a matter at hand? If you have, then you know how irritating it can be. Sometimes, supervisors stretch the range of their authority. Always be sure that the behavior you are addressing is in the domain of the work relationship. Just because you are supervising someone's clinical performance does not mean that you also have the right to comment on all personal attributes.

Know yourself. Transference, or projecting personal feelings about success or failure onto the employee, can make mincemeat out of a good feedback sandwich. A supervisor who transfers the need to succeed often responds to an employee's error with excessive emotion, jumps in prematurely and provides too much feedback. On the other hand, a supervisor who projects expectations for failure minimizes praise and overemphasizes criticism. When supervisors neglect to acknowledge and work through transference, they block their employees' development. Keep the responsibility of job performance squarely on the shoulders of the employee, and you will be in the best position to give balanced, accurate feedback.

Be dramatic. When giving feedback, non-verbal behavior is important too. Assertive supervisors demonstrate good eye contact, shoulder-to-shoulder posture, an open stance, appropriate affect and, for lack of a better word, a little drama. Feedback given in a monotone voice tends to go in one ear and out the other. Deliver your feedback with a dramatic force equivalent to its worth. If you are making a small point, use a softer voice and small gestures. After all, not everything you say hits 10 on the Richter scale of importance; but if it is a 10, present it like one. Wide eyes, increased or decreased volume, a rise in inflection, a pregnant pause, a shift in posture and a touch of humor can all convey: “You don't want to miss this one, so listen up!”

Be real. A little drama, or ham, makes a good point more likely to be heard and a feedback sandwich all the tastier; a little baloney makes it unpalatable. If your feedback is disingenuous, your employee will begin to discount what you say.

Provide closure. Ask the employee to respond to your feedback. Then paraphrase, or repeat, the employee's opinion. Paraphrasing does not suggest agreement, rather, it serves two purposes: It shows the employee that you accurately heard the expressed concerns, and it adds to the information you'll use in your final assessment. There is an added benefit as well. If you acknowledge the employee's views, you are likely to elicit a less defensive reaction when you repeat your assertion. Ask the employee if he or she has any questions, and, if suited to the interaction, end by clearly stating behavioral expectations.

If you think your assertiveness skills need work, two books you may find useful are: Your Perfect Right: Assertiveness and Equality in Your Life and Relationships by Robert Alberti and Michael Emmons and Asserting Yourself: A Practical Guide for Positive Change by Sharon Anthony Bower and Gordon H. Bower.

Start making sandwiches!

Great supervisors give great feedback. The feedback sandwich is one way to organize your feedback so it's more balanced and easier to deliver. By offering “keep behaviors,” or praise, at the same time you're offering “change behaviors,” or criticism, you demonstrate to employees that you see performance strengths as well as performance deficits. You also identify specific behaviors you want employees to repeat and behaviors you'd like them to change or stop. While more complex employee behaviors may require more than a feedback sandwich, most formative feedback can be accomplished in the context of the brief interactions I've mentioned here. With just a little practice, you'll soon become a star chef.