Using a clinical prediction tool at the point of care will help you choose which course is best for your patient.

Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13(4):41-44

Dr. Ebell is in private practice in Athens, Ga., and is associate professor in the Department of Family Practice at Michigan State University College of Human Medicine, East Lansing. He is also deputy editor for evidence-based medicine for American Family Physician. Author disclosure: nothing to disclose.

A 62-year-old man presents to you with cough, fever and chills, which he has had for three days. He has well-controlled hypertension and diabetes but is otherwise healthy. His respiratory rate is 24 breaths per minute, and his blood pressure and pulse are in the normal range. He has no signs of confusion. His white blood cell count is 23,000 cells per mm3 with 80 percent neutrophils, and his blood urea nitrogen is 14 mg per dL. Is outpatient treatment safe for this patient?

Looking to the evidence

Community-acquired pneumonia is often managed outside the hospital, an approach endorsed by evidence-based guidelines from the American Thoracic Society (ATS)1 and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).2 These guidelines do, however, recommend that physicians make an objective risk assessment using a prospectively validated clinical prediction tool to help guide them when deciding on inpatient or outpatient treatment. The most notable of these tools are the Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI) and several variations of the British Thoracic Society (BTS) rule, such as the CURB-65 (Confusion, Urea nitrogen, Respiratory rate, Blood pressure, 65 years of age and older) score.

The PSI1–6 was developed from an administrative data set of 14,199 adults and validated by the original investigators in a second group of 2,287 community-based and nursing home patients.3 It was subsequently validated in a number of populations, including 158 nursing home patients,6 3,181 patients at 32 Pennsylvania emergency departments4 and 1,024 patients at 22 community hospitals.5 In a prospective trial,7 hospitals were randomized to treat patients with community-acquired pneumonia using usual care or a PSI-based protocol. According to the protocol, patients presenting to the emergency department with community-acquired pneumonia who had a PSI risk class of I, II or III were treated as outpatients, although physicians used clinical judgment to overrule this criteria in some instances. On average, patients treated using the PSI protocol had greater severity of illness; however, they were less likely to be hospitalized, had shorter hospitalizations and had similar clinical outcomes compared with patients treated using usual care.7 An PSI calculator is available at http://pda.ahrq.gov/clinic/psi/psicalc.asp.

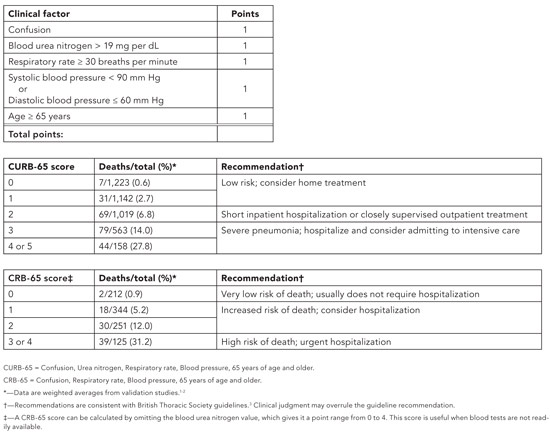

The CURB-65 and CRB-65 scores4,8,9 are easier than the PSI to calculate and interpret at the point of care. CURB-65 includes only five variables (compared with up to 20 in the PSI), and the CRB-65 score provides a four-variable substitute for use where blood testing is not immediately available.

The authors of the PSI recommend out-patient therapy for patients in PSI risk classes I and II, physician judgment for those in risk class III and hospitalization for those in risk classes IV and V.3 The IDSA guideline recommends that physicians consider home therapy for patients in PSI risk classes I, II and III.2 The BTS guideline recommends that physicians use the CURB-65 or the CRB-65 when deciding on inpatient or outpatient treatment.9 The ATS guideline recommends that physicians use validated clinical decision rules such as the PSI or the CURB-65 tool to support clinical judgment but does not define a recommended cutoff for hospital admission.1 A prediction rule that uses only clinical variables has been developed using data from nursing home patients; however, it has not been prospectively validated and was based on a retrospective chart review, which is less reliable than prospective data collection.10

All of the guidelines mentioned recommend that physicians use prediction tools to support, not replace, clinical judgment. External factors such as important comorbidities not included in the clinical rules (e.g., human immunodeficiency virus infection), previous failure of outpatient oral therapy and social factors (e.g., a patient’s inability to obtain or reliably take medication) are also appropriate considerations when deciding on inpatient or outpatient treatment.11

PNEUMONIA SEVERITY INDEX FOR COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA

Developed by Michael J. Fine, MD, Thomas E. Auble, PhD, Donald M. Yealy, MD, Barbara H. Hanusa PhD, Lisa A. Weissfeld, PhD, Daniel E. Singer, MD, et al. Copyright © 1997 Massachusetts Medical Society. Adapted with permission, 2006. Physicians may photocopy for use in their own practices; all other rights reserved. “Outpatient vs. Inpatient Treatment of Community-Acquired Pneumonia.” Ebell MH. Family Practice Management. April 2006:41–44; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20060400/41outp.html.

CURB-65 AND CRB-65 SEVERITY SCORES FOR COMMUNITY-ACQUIRED PNEUMONIA

Developed by Mark H. Ebell, MD, MS. Copyright © 2006 American Academy of Family Physicians. Physicians may photocopy or adapt for use in their own practices; all other rights reserved. “Outpatient vs. Inpatient Treatment of Community Acquired Pneumonia.” Ebell MH. Family Practice Management. April 2006:41–44; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20060400/41outp.html.

Applying the evidence

To treat the patient mentioned earlier, calculate his CURB-65 score rather than the PSI score because arterial blood gas measurements and radiography are not immediately available. The score is 0, which suggests that it is safe to treat him as an outpatient. Although his white blood cell count is elevated, this risk factor is not included in any of the three validated clinical decision rules.

POINT-OF-CARE SERIES

This article is part of a series that offers evidence-based tools to assist family physicians in improving their decision making at the point of care. The series is published in partnership with American Family Physician. A related article appears in the April 15 issue of AFP.

Past topics in this series include warfarin management, sore throat, pulmonary embolism, hypertension, acute otitis media, angioplasty risk and knee injury. All tools are available free online at https://www.aafp.org/fpm/toolbox.