Finding time for more patient visits may be easier and more lucrative than you think.

Fam Pract Manag. 2009;16(3):18-22

Dr. Mills practices in Newton, Kan., where he is a partner and department head in the Wichita Clinic. He is the AAFP's alternate delegate to the AMA's Relative Value Scale Update Committee and a member of the FPM Board of Editors. Author disclosure: nothing to disclose.

Few of us believe that family physicians are adequately paid for the value we deliver to our patients and to the health care system. In my work with the AMA's Relative Value Scale Update Committee (commonly referred to as the RUC), I am regularly reminded of how desperately we need primary care payment reform. I do see a better future for us on the horizon, but in the meantime, we have to make the best of the dysfunctional health care system in which we work. For the many of us whose compensation depends in part on our productivity, increasing gross revenue is one key to our success.

When I read several years ago that AAFP research had found that the most positive influence on physician income was a high number of billable visits per week,1 my first reaction was that this was obvious. However, on further reflection, I realized there's an important lesson in this finding. Physicians have a tendency to look for complicated strategies to increase gross revenue, such as adding an ancillary service we'd otherwise be happy not to bother with (cosmetic services, anyone?), when simply seeing more patients or offering more of the services our patients need would accomplish the same goal.

If you often leave the office with a waiting list of patients who wanted to be seen that day and couldn't get an appointment, you're losing revenue and risking the loss of patients to other practices. Accommodating them may not require extending your clinic's hours or forgoing that half-day off each week. It might just mean making the most of the time you currently have by fine-tuning your scheduling or improving your efficiency so that you have more appointment slots or opportunities for work-ins. If you don't mind working more hours – or if you end every day with two or three appointment slots you'd like to fill – you may need to take your practice on the road to other sites where patients need your services. This may be as complex as opening a satellite clinic in another town or as simple as arranging to provide care at a local nursing home, group home, rehabilitation center or jail.

You can also protect your revenue stream by being prepared to provide as many procedural services as is practical in your situation and by making sure you're billing for the minor procedures that you already perform but might not know you can be paid for.

This article describes these and other relatively simple strategies to increase your revenue starting today.

1. Review your scheduling practices

The single greatest thing we can do to increase our revenue may be to regularly work in an extra patient over the lunch hour or at the end of the day. The path to a healthier bottom line may be as straightforward as this.

Additionally, you may need to fine-tune the way your appointments are scheduled. If appointments are booked in standard 15-minute increments, you might be spending more time waiting for patients than you should. Or if appointments are all booked at the top of the hour (i.e., wave scheduling), your patients might be spending more time waiting for you than they should. I've found a “modified-wave” schedule to be the most efficient approach for my practice.

A modified-wave template schedules two 15-minute appointments on the hour, one appointment 15 minutes later and another appointment 30 minutes after the hour. Typically there is no appointment at 45 minutes after the hour, which allows time for a 30-minute appointment, an extra work-in patient, or time to return phone calls or catch up on documentation. A modified-wave template also helps to ensure that you're not behind schedule even before you begin. If you start seeing patients at 9 a.m. and one doesn't arrive on time, chances are the other patient with a 9 a.m. appointment will.

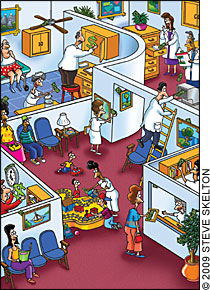

You should also consider whether your scheduler is getting the right visit type – or the right patient – in the right appointment slot. For example, diabetes checks may not require 30 minutes, especially if you have systems in place to ensure that lab results are available in the chart at the time of the visit. And certain patients will invariably consume the time of two appointments; book them accordingly. You can optimize your scheduling procedures by enabling easy communication between your scheduler and your clinical staff, for example, by putting their desks close to one another.

Open-access, also known as advanced-access or same-day, scheduling has emerged as a popular approach in the last 10 years. The list of FPM articles below includes one that explains the benefits of this method and how to implement it, as well as articles that describe other concepts mentioned here.

If your schedule is serving your practice well, your best option may be to focus on improving your efficiency.

FPM ARTICLES ON PRACTICE EFFICIENCY

“Huddles: Improve Offi ce Effi ciency in Mere Minutes.” Stewart EE, Johnson BC. June 2007; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20070600/27hudd.html.

“Ideas for Optimizing Your Nursing Staff.” Weymier RE. February 2003; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20030200/51idea.html.

“Same-Day Appointments: Exploding the Access Paradigm.” Murray M, Tantau C. September 2000; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20000900/45same.html.

“Seven Reasons to Dictate in the Presence of Your Patients.” Teichman PG. September 2001; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20010900/37seve.html.

“Strategies for Better Patient Flow and Cycle Time.” Backer LA. June 2002; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20020600/45stra.html.

“Tuning Up Your Patient Schedule.” Chung MK. January 2002; https://www.aafp.org/fpm/20020100/41tuni.html.

2. Work smarter

Improving efficiency is truly a game of inches. There are lots of ways to do it, and none are likely to result in dramatic gains, but if together they enable you to see two additional patients a day, the effort can amount to a tremendous increase in revenue (see the estimate below). According to the research referenced earlier, high-earning physicians work an average of 56 hours a week, and low-earning physicians work 51 hours a week. But the high-earners provide 38 more visits per week than their low-earning counterparts (high-earners provide a mean number of 122 visits per week; low-earners provide 84). The high-earners aren't just working harder; they're working smarter. These techniques can help you to do the same:

Have a huddle. Starting each morning with a 10-minute meeting of key clinical and office staff members can save you valuable time later. The purpose of a huddle is to look at the day's schedule, anticipate information needs or special circumstances that may arise during the day and plan accordingly to prevent slow downs. Check that lab results, reports from other physicians, discharge paperwork and so on are in the chart. Identify patient visits that might take more time than scheduled, and make adjustments. Talk with your scheduler about times when you might be able to see an extra patient.

Negotiate an agenda for the visit. This technique can be very helpful when patients arrive with lists, and even more helpful when they don't. We handle this informally in my practice. As the medical assistant is rooming the patient and taking vital signs, she asks, “Why are you here today?” and documents the patient's responses in the record. When necessary, I work with the patient to prioritize the list and plan our time effectively. Some practices take a more formal approach and ask patients to write on a tear-off pad or white board the things they want their doctor to address during the visit. This can help patients to focus and prevent “Oh, by the way” issues from surfacing late in the visit, and it can help doctors to see up front whether negotiation and prioritization are needed. (Note: The article on page 23 outlines a process for managing encounters with patients who bring lists.)

Don't leave the exam room during a visit. I can be most productive when I don't have to leave the exam room to obtain information or supplies that I need. By stocking exam rooms appropriately and implementing daily huddles as described earlier, you can avoid interruptions during patient visits. If 10 times a day you leave the exam room for two minutes to fetch a form or an instrument that you need, you've squandered the equivalent of an entire patient visit. Think about using your nursing staff to deliver to the patient any prescriptions, drug samples, patient education materials or other items that couldn't have been identified in advance so that you can move on to your next patient.

Delegate work that doesn't require a physician's license. Don't spend time on patient-care-related tasks that don't require a medical degree. For perspective, it can be helpful to ask yourself whether you would pay another doctor to do the same thing. Delegate as many administrative tasks as you can while still maintaining a good understanding of your practice's operations.

Dictate in the patient's presence. This takes some getting used to, and it may not be appropriate in every case, but dictating notes while you're still in the exam room with the patient can improve your efficiency. Your memory is fresh, and details are clear. Dictating in the patient's presence is also a good way of validating the patient's concerns, cementing your treatment alliance with the patient and reiterating your instructions.

Avoid batching your work. Dictating in the patient's presence is a good example of the kind of continuous flow process that you should strive for throughout your day. I try to dictate after every visit or two, instead of batching the dictation for a large number of visits at the end of the day. I actually used a stopwatch and timed myself for a week; I found that my average dictation took more than 50 percent longer when I did it at the end of the day.

Streamline your message traffic. Work closely with your nursing staff to try to minimize the number of times an individual request must change hands before a definitive answer is reached. This may involve establishing protocols to help ensure that your staff gathers all the information you need to make a decision before they pass along the message. Protocols that enable them to act on their own or with minimal input from you, as often as their license and skill level will allow, can also improve efficiency dramatically. Rather than dealing with phone messages and refill requests at lunch or the end of the day, try to deal with them between patient visits.

THE VALUE OF TWO EXTRA VISITS

$ 21,600

10 additional visits per week for 48 weeks; $45 per visit average

3. Keep multiple revenue streams, including procedures

It's important to realize the extent to which your scope of practice drives your revenue stream and to carefully weigh decisions that would narrow it. Whether it's performing a certain office procedure, seeing nursing home patients, doing obstetrics or taking care of patients in the hospital, think of each service as a tributary to your practice's revenue stream. Give up one of these services and you're cutting off part of your revenue stream, one that can be difficult to reclaim, particularly once procedural skills or privileges have lapsed.

My advice is to do every procedure you can comfortably and confidently perform in your setting. I did give up obstetrics, but I do almost every procedure you can imagine a family physician doing: skin procedures, joint aspirations and injections, trigger point injections, tendon and tendon sheath injections, simple- and moderate-complexity fracture care, treadmill stress tests and an array of hospital procedures. This scope wouldn't make sense in every practice, but it does work for mine. If you do procedures that your colleagues don't, invite them to refer their patients to you. The family physicians I practice with on occasion refer their patients to me for simple fracture care, pulmonary function test interpretation and joint injections rather than to the subspecialists in our multispecialty group; I return the favor with referrals for vasectomies. Another reason to maintain your procedural skills is that procedures pay better than the evaluation and management (E/M) services you're likely to replace them with (see "Procedures Pay More").

The following are examples of office procedures you might already be doing but not billing for. Although not all of my payers reimburse for these services (some bundle them with the related E/M service), I include them on our superbill and always bill for them. Don't get caught up in keeping track of exactly which payer covers which procedures this year; payment policies and coverage decisions change frequently enough that it's almost impossible to keep up. I encourage my partners to provide outstanding patient care, document everything they did and bill for everything they documented. This process will at least position you to receive the best payment you can, when you can. The only theoretical downside is an increase in charge-offs, or a potentially larger gap between gross and net charges. Of course payment amounts vary; the ones listed below are based on the 2009 Medicare fee schedule, not geographically adjusted, and they have been rounded to the nearest dollar:

90465, Immunization administration younger than 8 years of age (includes percutaneous, intradermal, subcutaneous or intramuscular injections) when the physician counsels the patient/family; first injection (single or combination vaccine/toxoid), per day; $21,

92567, Tympanometry (impedance testing); $18,

92552, Pure tone audiometry (threshold), air only; $21,

94150, Vital capacity, total (separate procedure); $18,

94664, Demonstration and/or evaluation of patient utilization of an aerosol generator, nebulizer, metered dose inhaler or IPPB device; $15 (I provide this service to patients for whom I'm prescribing an inhaler for the first time),

96110, Developmental testing, limited (e.g., Developmental Screening Test II or Early Language Milestone Screen), with interpretation and report; $13 (I do this testing as part of well-child visits),

46600, Anoscopy, diagnostic, with or without collection of specimen(s) by brushing or washing (separate procedure); $72.

| CPT code, descriptor | Work RVUs (relative value units) | Payment1 |

|---|---|---|

| 99214, Office or other outpatient visit for the evaluation and management of a new patient | 1.42 | $92.33 |

| 54150, Circumcision, using clamp or other device with regional dorsal penile or ring block | 1.9 | $172.76 |

| 20610, Arthrocentesis, aspiration and/or injection; major joint or bursa (e.g., shoulder, hip, knee joint or subacromial bursa) | .79 | $69.97 |

| 11400, Excision, benign lesion including margins, trunk, arms or legs; excised diameter 0.5 cm or less | .87 | $102.43 |

The bottom line

I'd be remiss if I failed to acknowledge that revenue is only part of the net income equation. A dollar of expense saved is every bit as good as a dollar of gross revenue earned. All practices should go over their expenses, both fixed and variable, with a fine-tooth comb. When combined with the additional revenue that the suggestions in this article can help to produce, some well-chosen cuts will make an even bigger difference in your bottom line.