Learn how a few procedural changes dramatically increased this practice's visit rates for well-child care.

Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18(5):26-30

Elizabeth Woodcock is a practice management consultant and principal of Woodcock & Associates Inc. in Atlanta. Eric Whicker is chief financial officer of Fort Wayne Medical Education Program (FWMEP), a family medicine residency program in northeastern Indiana. Leann Hostetler is a research nurse at FWMEP. Devon Nichols is director of compliance and quality with AmeriHealth Mercy of Indiana. Author disclosure: AmeriHealth Mercy engaged Elizabeth Woodcock to serve as a practice management consultant to FWMEP for the initiative described in the article.

Delivering quality patient care is goal number one for most medical practices, but good intentions are not always enough if your management processes keep getting in the way.

Fort Wayne Medical Education Program (FWMEP), a family medicine residency program in Indiana, reached this conclusion after one of its payers, AmeriHealth Mercy of Indiana, revealed less-than-stellar outcomes for patients who had selected FWMEP physicians for their care. As if that wasn't bad enough, the outcomes were for an especially important patient population – children insured by Indiana's Medicaid program.

To address this, the practice teamed with AmeriHealth Mercy of Indiana and a consultant (Woodcock) to improve its delivery of preventive care to children, honing in on well-child care for Medicaid patients. FWMEP quickly recognized that roadblocks of its own making were preventing the practice from reaching its goals. By removing these roadblocks as described below, FWMEP is improving its quality indicator scores and, most important, giving patients the care they need. We hope that other practices can learn from our experience.

Scheduling visits more effectively

As a busy practice seeing 100 patients a day, FWMEP excelled at quickly scheduling patients with acute problems. Fifteen appointment slots were held open for acute care each morning and afternoon. Patients who needed only preventive care didn't “qualify” for these slots, so they were given appointments two or more weeks out. This policy exacerbated the chronically high rate of cancellations and no shows for appointments with Medicaid-insured children. The parents and guardians of these patients face numerous challenges – arranging childcare, adjusting work schedules and finding transportation, to name a few – so setting appointments to suit our schedule instead of their schedule posed a significant roadblock. Recognizing this, FWMEP reduced its restrictions on appointment availability for preventive care, initiating a modified open-access system for all appointment requests.

The practice also redoubled its efforts to encourage parents and guardians to schedule well-child checks for their children. The practice now identifies patients who need well-child care by querying monthly member reports provided by AmeriHealth Mercy of Indiana and calling their parents and guardians to offer appointments. Staff spend from one to three hours a day on this work, which includes identifying patients newly assigned to the practice and then calling each one to welcome them to the practice and schedule a well-child check.

The practice developed two brochures that highlight the need for preventive care, one for young children and the other for adolescents. These are given to patients and parents at their appointments, and the practice plans to broaden distribution to patients who are not scheduling preventive exams regularly.

The practice also plans to implement an appointment recall process driven by its electronic health record system (EHR) to ensure follow-up on all patients to whom it has recommended care.

Providing two visits in one

After analyzing payer reports, FWMEP discovered that 35 percent of the pediatric patients assigned to the practice had been seen for acute issues during the first eight months of the year but weren't up-to-date on well-child care. Although the practice routinely asked parents and guardians at checkout to schedule well-child care, the majority failed to keep their appointments. Adding to the challenge was the fact that the practice could not schedule appointments more than 13 weeks out due to internal constraints regarding physician schedules. If the well-child appointment couldn't be scheduled at checkout, a staff member handed the parent or guardian a reminder card and asked them to call back in a few months; however, the practice did not follow up. The practice came to realize that the best opportunity to provide well-child care for these patients was when they were seen for an acute problem.

One hurdle to implementing a “double visit” protocol was a lack of coding and reimbursement knowledge among the practice's physicians. They wanted assurance that a well-child check (CPT codes 99381-99387; 99391-99397) would be paid for when billed with a problem-focused office visit provided the same day (CPT codes 99201-99215; 99211-99215). Physicians were taught how to distinctly document both services in the patient's electronic health record and properly code them with use of modifier 25 to indicate that a significant, separately identifiable service was provided on the same day. (For more on modifier 25, see “Understanding When to Use Modifier 25,” FPM, October 2004.) The practice con-firmed with the payer that payment would be provided for both services, and business office staff reviewed remittances to verify payment.

Next FWMEP turned its attention to making sure that recommended well-child care could actually be addressed in the context of the acute care visit. The practice instructed its schedulers to add 10 minutes to all pediatric acute-care appointment slots with the expectation that both the acute visit and a well-child check would be performed. Initially this created consternation, but a careful review revealed that adding 10 minutes to accommodate well-child checks was not disruptive and in fact optimized the physician's time. The practice's reduction in no-shows for separately scheduled pediatric preventive visits more than offset the reduction in pediatric acute-care appointments. Volume actually increased.

The practice's EHR system became an essential tool for identifying needed preventive services at the point of care when alerts for age-appropriate immunizations were added to the system. The EHR was programmed to display an alert for preventive care whenever an FWMEP nurse logs in to a pediatric patient's record to initiate a patient encounter. In addition, the practice trained physicians and nurses to use templates specific to visit types to navigate patient encounters and ease documentation, which improved efficiency.

To further encourage improving immunization rates and the percentage of children receiving well-child care, the practice is evaluating offering a productivity incentive, gasoline gift cards, to all staff.

TIPS FOR IMPROVING WELL-CHILD VISIT RATES

Reduce restrictions on appointment availability.

Use payers' monthly member reports to identify pediatric patients newly assigned to the practice; call each family to welcome them and schedule a well-child visit.

Develop an information sheet that highlights the importance of preventive care. Give this to patients and their parents at acute care appointments.

Implement a reminder system and recall process to ensure that patients' parents follow through on recommended preventive care.

Provide well-child care for patients when they are seen for an acute problem; check with payers to confirm that same-day acute and well-child care are separately billable.

Use visit-specific templates for reminders and to ease documentation.

Evaluate missed-appointment letters to ensure that contact information and tone are right.

Ask payers what they will do to support your efforts.

Use an appointment reminder system; consider warm calls in addition to automated ones.

Rather than turning away patients who arrive late, allow the physician to determine whether he or she can still see them.

Have physicians deliver discharge paperwork for newborn patients directly to the practice's triage nurse to contact the parents about scheduling newborn and postpartum visits.

Reducing missed appointments

A 14 percent no-show rate made missed appointments an obvious target for the performance initiative. The rate of no-shows for well-child checks with Medicaid patients was significantly higher, at 22 percent. Even more disheartening was realizing that 14 percent of all scheduled visits and 13 percent of Medicaid scheduled well-child checks resulted in cancellations. Because those slots were not rebooked, the overall rate of missed encounters was 28 percent for all patients and 35 percent for Medicaid well-child checks.

To address these issues, the practice took a closer look at the letters sent to patients who missed their appointments. FWMEP discovered that although they asked patients to reschedule, the letters contained no information about how to contact the practice. The practice designed a new letter displaying the practice's phone number prominently and using less confrontational language to advise patients of the “missed” (rather than “failed”) appointment. FWMEP also gained the support of AmeriHealth Mercy of Indiana, which agreed to handle communications when patients missed three or more appointments.

The practice also revised its procedure for appointment confirmation calls. Although patients continue to receive appointment reminders from an automated system two days prior to their scheduled appointment, the front office staff also makes “warm calls” the day before the appointment to parents or guardians of children scheduled for well-child checks.

Finally, the practice decided to take a different approach when patients arrive more than 20 minutes late for appointments. Rather than turning them away, the front office contacts the patient's physician to determine whether he or she can still see the patient.

Increasing newborn care

A quick review of the compliance rate for newborn visits revealed a gap that the practice knew it needed to close, starting with a revision of the discharge paperwork given to new mothers. Buried in a litany of postpartum advice was a one-line statement in small print with instructions to call the practice to make an appointment for postpartum care four weeks after delivery. The instructions did not address the need for a newborn visit at all. Because the practice had no tracking system, if the appointment wasn't scheduled the practice might never see the mom or baby again – or recognize that it should.

To prevent postpartum and initial newborn care from falling through the cracks, the physicians who provide hospital care to moms and babies now carry the discharge paperwork for each of their patients to one of the two triage nurses employed by the practice. The nurse follows up directly with the patient to schedule the newborn and postpartum visits. Patients receive an automated confirmation call two days before these appointments, and the practice added a “warm call” as well.

The practice is considering developing a postpartum and nursery standing-order sheet to instruct hospital ward clerks to contact the practice before the patient is discharged from the hospital to schedule the postpartum and newborn checks.

Positive results

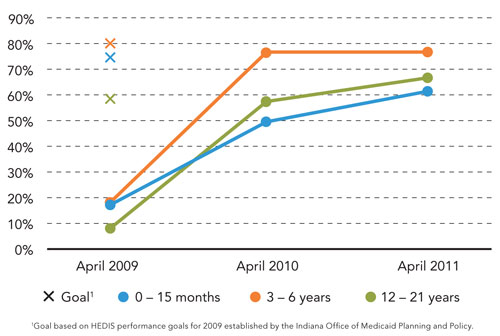

Improvement resulted quickly following the implementation of these changes. The volume of Medicaid well-child checks increased by 32 percent. In addition, the practice dramatically increased the percentage of Medicaid pediatric patients who receive well-child checks at recommended intervals (see the graph below). Data collected at the end of the second year show that performance has continued to improve.

PERCENTAGE OF PEDIATRIC MEDICAID PATIENTS RECEIVING WELL-CHILD CHECKS AT RECOMMENDED INTERVALS

The new scheduling protocols – welcome calls to new patients, confirmation calls for all well-child checks and postpartum follow-up calls – were accommodated by existing staff after streamlining and redistributing workloads. Supported by a system that makes better use of providers' time, instead of just adding more hours, the practice's volume and revenue both increased. Most important, children are receiving the preventive care they need. This initiative has shown that improving outcomes may involve much more than reviewing what goes on in the exam room. Better outcomes may well depend upon uncovering and removing the roadblocks a practice creates in how it manages access.

Editor's note: The authors wish to acknowledge the contributions of the following individuals, all from the Fort Wayne Medical Education Program: James E. Buchanan, MD, Robert Wilkins, MD, Rebecca Baker-Palmer, MD, Aaron Coray, DO, J. David Kunberger, MD, Vip Mangalick, MD, Mycal Mansfield, MD, Henry Mao, MD, Matthew McIff, MD, Mahnaz Qazi, MD, ShaRonda Shaw-Berrocal, DO, Rowena Yu, MD, and Sue Stone, RN.