Partnering with local groups that work with seniors can help you meet the special needs of older patients.

Fam Pract Manag. 2014;21(5):13-17

Author disclosures: The John A. Hartford Foundation provided financial support for this article. The sponsor had no role in the preparation, review, or approval of this article.

Geriatric patients with complex health problems are increasingly dominating primary care practices. Their challenging conditions stretch the time limits of a typical visit and tax a clinic's staff. The experience often frustrates the primary care physician as well as the patient and his or her caregivers.

Physicians may be uncertain about treating common geriatric conditions, such as falls and memory loss.1 But ignoring these conditions can complicate the management of diabetes, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and other chronic diseases.2 One of the greatest challenges for primary care practices is helping patients change their behavior to promote healthy living and manage their chronic illnesses.1

A 2012 national survey of older patients found that only 7 percent had received seven services recommended for healthy aging: an annual medication review, a falls risk assessment, a falls history, depression screening, referral to community-based health resources, and discussions of their ability to perform both routine daily tasks and activities without help. Fifty-two percent reported receiving none or only one of these services, and 76 percent received fewer than half.3

The National Committee for Quality Assurance's standards for the patient-centered medical home model recognize the importance of practices supporting patient self-care and facilitating access to community resources.4 Because many practices do not have the resources to support patients in the self-management of chronic conditions or to optimally manage the concomitant geriatric conditions, primary care physicians are encouraged to explore partnerships with community-based organizations (CBOs).5

What do community-based organizations offer?

Many local CBOs, such as area agencies on aging, social service agencies, senior centers, day centers, or faith-based organizations, already have established programs that address common geriatric conditions and are well-positioned to help optimize care delivery to geriatric patients.6,7 Local agencies on aging can be identified through a national locator, whereas other services, such as those offered by Catholic Charities, Jewish Family Services, senior centers, and more can be identified through the United Way.

CBOs offer many advantages. Their programs are often conveniently located in the community and are tailored to the special needs of the older population. CBO staff and volunteers are typically members of the same local community and attuned to participants' cultural needs and preferences. Because many of these organizations develop long-term relationships with their clients, staff and volunteers often have insight into their living situations and social support networks.

The U.S. Administration on Aging, through its national network of CBOs, supports a comprehensive Health, Prevention, and Wellness Program with offerings that address major conditions and risk factors affecting geriatric adults, such as chronic disease self-management, fall prevention, dementia care, increased physical activity, screening for and management of depression and substance abuse, medication management, and care transitions. CBOs serving older adults also have a long history of delivering in-home or group meals and can customize meals to meet specific dietary needs, such as those for diabetes and heart disease.

An increasing number of CBOs are offering the Stanford University Chronic Disease Self-Management Program, a group workshop that has been demonstrated to improve health outcomes and reduce health utilization.7,8,9 Trained peer leaders facilitate these groups and provide education and support for self-management. In addition, many CBOs offer disease-specific programs developed in partnership with local chapters of advocacy groups, such as the American Diabetes Association or the Alzheimer's Association, that are overseen by a nurse, social worker, or health educator.

Getting started

The wide range of potential programs and services offered by CBOs can be a bit challenging to navigate for the physician who is just getting acquainted with these organizations. The mantra of geriatric care, “start low and go slow,” may also be applicable to establishing partnerships with CBOs. Physicians might begin by first choosing the two or three most challenging problems in their practice and identifying the CBOs that best address these problems. They could also ask CBOs to assess the patient population and make their own recommendations on ways they could help reduce the workload of the physician's office staff. Further, if the physician knows that a collaborating CBO can accept a referral to assist individual patients with challenging medical or social problems, he or she may be more confident initiating a discussion with a patient on the subject. A simple guide is available to help physicians foster collaborations with community organizations.10 Here are some examples of how partnerships with CBOs benefited several patients and the physicians who care for them:

Case 1. J.M. is a 78-year-old female with mild to moderate dementia who lives alone. Her primary care physician became increasingly concerned with her medication adherence because of her frequent confusion. The physician referred J.M. to the local agency on aging. Following a home visit, a care manager developed a plan for working with J.M.'s family and her insurance company to ensure that J.M. was getting the correct medications. Specifically, the care manager installed a medication-dispensing machine and developed a reliable strategy to ensure that the machine would be refilled weekly.

Case 2. E.N. is an 80-year-old female. Her primary care physician, concerned about E.N.'s safety because of her progressing cognitive impairment, referred her to an elder care services agency. Although E.N. had family in the area, she lived alone. The agency's care manager connected the family with the local chapter of the Alzheimer's Association, which helped E.N.'s family learn strategies to ensure her safety. The care manager also conducted a home evaluation and determined that E.N. was eligible for additional in-home supportive services. The physician and E.N.'s family were relieved with the support, and E.N. has continued to live in the community in a safe and supportive environment.

Case 3. L.N. is a 73-year-old male who has diastolic dysfunction, morbid obesity, diabetes, osteoarthritis that restricts the use of his right arm, and severe lymphedema that requires frequent wrapping of bandages around his legs. His comorbidities translated into limited physical function and a serious risk for falls and injuries. The Medicare benefits that supported his leg wrapping were running out, and he was unable to do this himself. L.N. was referred to an evidence-based fall prevention program conducted by an area agency on aging. The program ran two-and-a-half hours per week for six weeks. By the end of the program, L.N. had regained considerable physical function, had not experienced any falls, and had gained the strength and mobility needed to apply his own bandages. As a result of L.N.'s lifestyle changes, his physician has been able to stop or decrease the dose of some medications.

Maintaining communication

Two-way communication is essential for primary care practices and CBOs to effectively work together. Early in their collaboration, both parties need to consider who on their staffs will be primarily responsible for communicating with the other side (e.g., the physician may designate a staff member to coordinate CBO referrals) and how they should communicate (e.g., directly via email or phone, or through the patient).

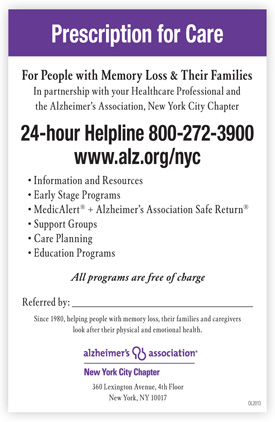

One of the first steps in formulating the physician-CBO collaboration might be to develop a referral and communication template that includes the essential information needed by each office and that can be easily incorporated into the office routine. (See “Community-based organization referral form.”) Ideally, a single form could be used to make referrals to multiple CBOs.An alternative would be to develop a prescription-pad-style referral form for each program of interest, such as physical activity, incontinence, or Alzheimer's support, and include contact information. (See “Example of prescription-pad-style referral form.”)

COMMUNITY-BASED ORGANIZATION REFERRAL FORM

Fax to: ____________________________ Fax #: _____________________________

Description of program: __________________________________________________

Physician referral is required.

Referred by: ___________________________________________________________

Phone: ________________________________________________________________

Date of referral: ________________________________________________________

Why is this patient being referred? ________________________________________

__________________________________________________________________________

Patient name: _____________________________________ DOB: ________________

Insurance type/#: _______________________________________________________

Patient address: ________________________________________________________

Phone #: ______________________ Alternate #: _____________________________

Email: _________________________________________________________________

Family caregiver name: ___________________________ Phone #: _______________

Has the patient been given information about the program? □ Yes □ No

Just as the physician's office needs to know how to contact the CBO staff, CBO staff need to know how to reach the physician's office to report changes in the patient's health status, receive clarification, or suggest changes to the treatment plan. To ensure appropriate safeguards for privacy, the physician and CBO may consider entering into a formal business associate agreement to facilitate patient information sharing and care planning, and to ensure HIPAA compliance.11 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has information on creating a HIPAA business associate agreement at http://1.usa.gov/1iifjv5.

EXAMPLE OF PRESCRIPTION-PAD-STYLE REFERRAL FORM

Potential benefits and challenges

Collaborating with CBOs has many potential advantages. CBO staff can help patients achieve their health goals by providing ongoing support and positive reinforcement, which is important given that these interventions often require the geriatric patient to change his or her behavior or to assume a greater role in disease self-management. They can serve as an additional set of “eyes and ears,” monitoring the patient's health status and communicating changes back to the physician.

You can also legitimately capture some of the costs of collaborating with CBOs to manage the care of older patients through compensation of some services under Medicare. For instance, since January 2013, providers can bill the Medicare fee-for-service program for providing transitional care management to their patients who were recently discharged from a hospital or skilled nursing facility. These new CPT codes (99495 and 99496) encompass face-to-face and non-face-to-face contact with the patient, family caregivers, and other health care professionals, including home care professionals and CBOs. The non-face-to-face services also include such activities as identifying available community and health resources and facilitating access to care and those services needed by the patient or family.12 At the time of this writing, Medicare is also exploring a chronic care management code that would provide similar care coordination incentives without requiring a recent hospital discharge. (For more information, see this recent post on the FPM Getting Paid blog.)

In addition to these benefits, however, there are challenges. First, CBOs may have limited capacity within their programs, and that could delay access to their services. This isn't universal, however, as a National Council on Aging survey reported that less than one-third of programs had a waiting list. Waiting lists are more common for in-home support services as opposed to workshops or support groups.6 But physicians working in less populated areas may find relatively limited coverage for key programs and services.

Physicians also often lack the time needed to discuss the benefits of a CBO program with a patient and initiate a referral. It might be more appropriate for another member of the office staff, such as a medical assistant or a receptionist, to facilitate the referral. Asking the patient to follow-up independently might be feasible if he or she is able and motivated to participate. For cognitively impaired patients, engaging a family caregiver in the initial referral and in subsequent follow-up is recommended. Irrespective of who initiates the referral, however, the CBO will still rely on the physician or a designated staff member to provide timely clarification of aspects of the patient's treatment plan or report a change in the patient's health status.

Finally, patients may be reluctant to attend a program at a CBO, particularly if they have not had any interaction with the CBO previously. In addition to offering an enthusiastic endorsement of the program, the physician or a member of the physician's staff may engage the patient in motivational interviewing to better understand the patient's reluctance and identify ways to overcome perceived barriers. (For more information, see “Encouraging Patients to Change Unhealthy Behaviors With Motivational Interviewing,” FPM, May/June 2011.) The physician or a member of the physician's staff may also enlist the support of a social worker or intake counselor from the CBO to contact the patient by telephone to address any concerns. In some instances, multiple conversations may be needed before the patient agrees to the referral.