A more recent article on acute pericarditis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(10):1509-1514

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Although acute pericarditis is most often associated with viral infection, it may also be caused by many diseases, drugs, invasive cardiothoracic procedures, and chest trauma. Diagnosing acute pericarditis is often a process of exclusion. A history of abrupt-onset chest pain, the presence of a pericardial friction rub, and changes on electrocardiography suggest acute pericarditis, as do PR-segment depression and upwardly concave ST-segment elevation. Although highly specific for pericarditis, the pericardial friction rub is often absent or transient. Auscultation during end expiration with the patient sitting up and leaning forward increases the likelihood of observing this physical finding. Echocardiography is recommended for most patients to confirm the diagnosis and to exclude tamponade. Outpatient management of select patients with acute pericarditis is an option. Complications may include pericardial effusion with tamponade, recurrence, and chronic constrictive pericarditis. Use of colchicine as an adjunct to conventional nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy for acute viral pericarditis may hasten symptom resolution and reduce recurrences.

Acute pericarditis is a common disease that must be considered in the differential diagnosis of chest pain in adults.1 The clinical syndrome of pericarditis results from inflammation of the pericardium, a fibrous sac that envelops the heart and the base of the great vessels. The pericardium has a visceral and a parietal layer, between which up to 50 mL of serous fluid is found in healthy patients.2 Pericarditis may present as an indolent process with no significant pain, as seen in patients with tuberculosis, or it may be heralded by the sudden onset of severe substernal chest pain in acute idiopathic or viral pericarditis.

Although the incidence of acute pericarditis is unknown, up to 5 percent of visits to emergency departments for nonacute myocardial infarction (MI) chest pain may be related to pericarditis.3 Recognition of the clinical syndrome is important because it must be distinguished from acute coronary syndromes and pulmonary embolism. Further, the syndrome may lead to cardiac tamponade or constrictive pericarditis, or may be associated with underlying conditions (e.g., acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS], malignancy, MI, collagen vascular disease).

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography is recommended for patients with suspected pericardial disease, including effusion, constriction, or effusive-constrictive process. | C | 10, 25 |

| Pericardiocentesis should be reserved to treat cardiac tamponade and suspected purulent pericarditis. | C | 10, 25 |

| Colchicine should be considered as an adjunct to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapy in patients with acute viral or idiopathic pericarditis. | B | 28, 29 |

| Corticosteroid therapy alone should be avoided in patients with acute or idiopathic pericarditis. | B | 29 |

Etiology

| Idiopathic (nonspecific, probably viral) | |

| Infectious causes | |

| Viruses: coxsackievirus A and B, hepatitis viruses, human immunodeficiency virus, influenza, measles virus, mumps virus, varicella virus | |

| Bacteria: gram-positive and gram-negative organisms; rarely, Mycobacterium tuberculosis | |

| Fungi (most common in immunocompromised patients): Blastomyces dermatitidis, Candida species, Histoplasma capsulatum | |

| Echinococcus granulosus | |

| Noninfectious causes | |

| Acute myocardial infarction* | |

| Aortic dissection | |

| Renal failure† | |

| Malignancy: breast cancer, lung cancer, Hodgkin's disease, leukemia, lymphoma by local invasion | |

| Radiation therapy (usually for breast or lung cancer) | |

| Chest trauma | |

| Postpericardiotomy | |

| Cardiac procedures: catheterization, pacemaker placement, ablation | |

| Autoimmune disorders: mixed connective tissue disorder, hypothyroidism, inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, spondyloarthropathies, systemic lupus erythematosus, Wegener's granulomatosis | |

| Sarcoidosis | |

| Medications | |

| Dantrolene (Dantrium), doxorubicin (Adriamycin), hydralazine (Apresoline; brand not available in the United States), isoniazid (INH), mesalamine (Rowasa), methysergide (Sansert; brand not available in United States), penicillin, phenytoin (Dilantin), procainamide (Procanbid), rifampin (Rifadin) | |

Pericardial disease is the most common cardiovascular manifestation of AIDS, occurring in up to 20 percent of patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection/AIDS. Although the incidence of bacterial pericarditis is declining in developed countries, it has increased among patients with AIDS.8,9 Patients with AIDS and other immunocompromised persons are also at high risk for tuberculous and fungal pericarditis.

The mortality rate for untreated tuberculous pericarditis approaches 85 percent. Tuberculous pericarditis often presents with subacute illness that includes fever, a large pericardial effusion, and tamponade. The diagnosis is confirmed by identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in pericardial fluid or tissue. Other diagnostic tools include polymerase chain reaction for DNA of mycobacteria, adenosine deaminase, and interferon-γ in pericardial fluid.10

Pericarditis also can arise as a complication of MI. Post–MI pericarditis may develop two to four days after an acute infarction and results from a reaction between the pericardium and the damaged adjacent myocardium. Dressler's syndrome is a post–MI phenomenon in which pericarditis develops weeks to months after an acute infarction; this syndrome is thought to reflect a late autoimmune reaction mediated by antibodies to circulating myocardial antigens.2

Pathophysiology

The acute inflammatory response in pericarditis can produce either serous or purulent fluid, or a dense fibrinous material. In viral pericarditis, the pericardial fluid is most commonly serous, is of low volume, and resolves spontaneously. Neoplastic, tuberculous, and purulent pericarditis may be associated with large effusions that are exudative, hemorrhagic, and leukocyte filled.2,11 Gradual accumulation of large fluid volumes in the pericardium, even up to 250 mL, may not result in significant clinical signs.12

Although pericardial effusion may be absent in 60 percent of patients, large pericardial effusions may accumulate rapidly and impede diastolic filling of the right heart, resulting in cardiac tamponade and death.1,3,11 Cardiac tamponade associated with acute pericardial disease is more common in patients with neoplastic, tuberculous, and purulent pericarditis (60 percent) than in patients with acute viral pericarditis (14 percent).11,13

Prolonged pericarditis may result in persistent accumulation of pericardial fluid. In this case, the fluid constitutes to form a thick coating that surrounds the myocardium. The ultimate manifestation may be constrictive pericarditis.4

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Patients with acute pericarditis commonly report a prodrome of fever, malaise, and myalgias. The cardinal features of acute pericarditis are chest pain, pericardial friction rub, and gradual repolarization changes on electrocardiography (ECG).4,14,15 In patients with acute pericarditis, chest pain is abrupt in onset, pleuritic, and substernal or left precordial in location. It may radiate to the trapezius ridge, neck, arms, or jaw. The pain is relieved by leaning forward and is made worse by lying supine. The classic triphasic pericardial rub is best heard along the left sternal border with the patient sitting up and leaning forward (Table 2).7

Although auscultation of a pericardial friction rub has high specificity (approaching 100 percent) for acute pericarditis, it has low sensitivity that varies with the frequency of auscultation.15,16 The pericardial rub is best auscultated with the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the left lower sternal border in end expiration with the patient leaning forward. It has a rasping or creaking sound similar to leather rubbing against leather.

The classic pericardial rub is triphasic but occurs in only one half of patients with a rub, whereas the remainder of patients have a biphasic or monophasic rub. The three phases of the pericardial rub correspond to the movement of the heart against the pericardial sac during atrial systole, ventricular systole, and rapid ventricular filling. The rub of pericarditis may be transient, making it important for physicians to auscultate the heart repeatedly.4,5,15 The presence of a monophasic rub occurring with the respiratory cycle in the absence of diagnostic changes on ECG or elevated cardiac enzymes should alert physicians to the possibility of pleuritis.3

Physical findings that suggest acute cardiac tamponade include tachypnea, tachycardia, neck vein distention, hypotension, and inspiratory fall in arterial blood pressure. Echocardiographic evidence of diastolic chamber collapse of the right atrium, right ventricle, or both serves to confirm tamponade.4

Tuberculous pericarditis presents differently. A study of 233 patients found that fever, night sweats, weight loss, elevated serum globulin, and normal peripheral white blood cell count were independent predictors of tuberculous pericarditis and could be used in a clinical decision tool for making an accurate diagnosis.17

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

Superficial myocardial inflammation is believed to explain the four stages of ECG changes visible during acute pericarditis.18 These stages involve diffuse, upwardly concave ST-segment elevation; T-wave inversion; and PR-segment depression.19,20 The evolution of these ECG changes helps distinguish pericarditis from early repolarization and acute MI19 (Table 27 ).

In stage I, which can last a few hours to several days, ST segments elevate, T waves remain upright, and PR segments are isoelectric or become depressed. After a few days, the ST and PR segments normalize, typifying stage II. In stage III, diffuse T-wave inversions remain after the ST segments have normalized. The ECG returns to normal in stage IV unless chronic pericarditis develops, leading to persistence of T-wave inversion.20 No reciprocal changes or Q waves are found in the 12-lead ECG during acute pericarditis, which is an important feature in distinguishing acute pericarditis from acute MI.13,21,22

The changes in stage I may be confused with findings of MI or early repolarization; old ECGs help differentiate among these conditions. It is important to remember that no PR-segment depression occurs in MI. The absence of PR-segment depression, however, does not rule out acute pericarditis because it may be found in about 25 percent of cases. In addition, the ST-segment elevation in acute infarction is upwardly convex in concordant leads, and Q waves often appear. The most reliable differential finding in the ECG is the ratio of the magnitude of the ST-segment elevation to the T-wave amplitude in the V6 lead; acute pericarditis is more likely when the ratio is greater than 0.25.19,23

Acute pericarditis is often associated with elevated markers of acute inflammation, including C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and leukocyte count. Markers of myocardial injury such as the MB isoenzyme of creatine kinase and cardiac troponins are often elevated. Troponin I elevation occurs in patients with ST-segment elevation and likely corresponds to epicardial cell damage. This type of cell damage in patients with acute pericarditis is seen in especially young patients and in those with recent infection. Family physicians should consider consultation with a cardiologist for patients with an atypical pericarditis presentation and elevated troponin I.24

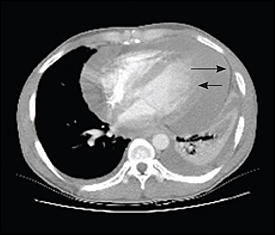

In patients with suspected pericarditis, echocardiography helps detect pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, and underlying myocardial disease.10,25 When pericardial effusion is found in the setting of clinical pericarditis, the diagnosis is confirmed. However, results of echocardiography may be normal in patients with the clinical syndrome of pericarditis.10 Computed tomography (Figure 1) and magnetic resonance imaging are useful if the initial work-up for pericarditis is inconclusive.10

RECOMMENDED DIAGNOSTIC STRATEGY

Most cases of acute pericarditis are idiopathic, and initial work-up should be limited to a history and physical examination, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, troponin I, serum chemistry, ECG, chest radiography, and echocardiography. For patients with tamponade, those with no known associated illness (Table 1),5–7 and those in whom pericardial disease does not improve within one week, antinuclear antibodies, rheumatoid factor, and mycobacterial studies (i.e., cultures of sputa and gastric aspirate) should be obtained.13

If pericardiocentesis is ineffective or tamponade recurs, subxiphoid pericardial drainage and biopsy with histology and cultures are recommended.13 The diagnostic yield for pericardiocentesis and pericardial biopsy is about the same (19 percent).14 The yield increases to 34 percent when either procedure is performed therapeutically, as for patients with symptomatic cardiac tamponade. Some experts recommend that pericardiocentesis not be performed exclusively for diagnostic purposes unless purulent pericarditis is strongly suspected.14,26

Treatment

The goal of treating acute viral pericarditis is to relieve pain and to prevent complications such as recurrence, tamponade, and chronic restrictive pericarditis. Because most episodes of acute pericarditis are uncomplicated, many patients may be managed in the outpatient setting.26,27 Indications for hospitalization of patients with acute pericarditis are listed in Table 3.26 When tamponade is identified, pericardiocentesis is the intervention of choice.13 If the patient has no poor prognostic indicators (e.g., body temperature > 100.4° F [38° C], findings of tamponade, history of immunocompromise or trauma) and the basic laboratory studies discussed earlier are reassuring, outpatient management is an option.24

| Anticoagulation therapy |

| Body temperature greater than 100.4° F (38° C) |

| Echocardiographic findings of a large pericardial effusion |

| Findings of cardiac tamponade (i.e., hypotension and neck vein distention) |

| History of trauma and compromised immune system |

| Myopericarditis |

| Troponin I elevation |

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, including aspirin and ibuprofen (Motrin), have been used to relieve chest pain, fever, and friction rub in patients with acute pericarditis.10,24–26 Aspirin (up to 800 mg every six hours) and ibuprofen (300 to 800 mg every six hours) are conventional therapies.10

The authors of two recent randomized controlled trials examined the value of colchicine in the treatment of acute and recurrent pericarditis.28,29 Participants in each study received either conventional treatment with aspirin (800 mg orally every six or eight hours for seven to 10 days with gradual tapering over three to four weeks) or aspirin at the same dose combined with colchicine (1.0 to 2.0 mg for the first day, then 0.5 to 1.0 mg daily for three months). Patients intolerant of aspirin were given a tapering dose of prednisone over one month.29

The addition of colchicine reduced the recurrence rate of pericarditis at 18 months (32.3 percent for aspirin or prednisone alone, 10.7 percent for an anti-inflammatory plus colchicine; P = .004; number needed to treat [NNT] = 5). Addition of colchicine also decreased symptom persistence at 72 hours (11.7 percent versus 36.7 percent for aspirin or prednisone alone; P = .003; NNT = 4).29 Results were similar for patients with recurrent pericarditis.28

Use of corticosteroids alone was an independent risk factor for the subsequent recurrence of pericarditis in this study,29 although corticosteroids may be useful in refractory acute pericarditis. Side effects in the colchicine and noncolchicine groups were similar. This study was limited by an open-label design and the use of the subjective end points of symptom recurrence, but the results29 provide some evidence that colchicine should be considered as an adjunct to anti-inflammatory drugs, and that corticosteroids should be used with caution.

Prognosis

Generally, acute pericarditis is benign and self-limiting. Occasionally, acute pericarditis will be complicated by tamponade, constriction, or recurrence. Nearly 24 percent of patients with acute pericarditis will have recurrence. Most of these patients will have a single recurrence within the first weeks after the initial episode, and a minority may have repeated episodes for months or years. The first episode of viral pericarditis is usually the most severe, whereas recurrences are less severe and may present only with chest pain.16