Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(9):2507-2512

Acute pancreatitis is a rare finding in childhood but probably more common than is generally realized. This condition should be considered in the evaluation of children with vomiting and abdominal pain, because it can cause significant morbidity and mortality. Clinical suspicion is required to make the diagnosis, especially when the serum amylase concentration is normal. Recurrent pancreatitis may be familial as a result of inherited biochemical or anatomic abnormalities. Patients with hereditary pancreatitis are at high risk for pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatitis is a disease process with multiple triggers that may cause activation of proteases within the pancreas. It is rare in children, and the causes are more varied in children than in adults (70 to 80 percent of adult cases are related to either alcohol intake or gallstones). In about 25 percent of childhood cases, the etiology is unknown, but trauma, multisystem disease and drugs account for most identified causes.1

Illustrative Case

A 10-year-old boy was examined in the emergency department because of increasingly severe abdominal pain and vomiting over a three-day period. He had a history of nine previous hospitalizations for similar symptoms, beginning at about one year of age. He had also had numerous episodes of abdominal pain without significant vomiting, which had been managed at home. There was no family history of abdominal problems other than cholelithiasis in his mother. He had not required hospitalization since an appendectomy performed two years previously. No serum amylase value was found on review of old charts.

On examination, the young boy appeared to be mildly dehydrated and had moderate epigastric tenderness without significant abdominal distention. Vital signs were within normal limits. Results of laboratory studies were normal with the exception of elevated amylase and lipase concentrations. The serum amylase level was 279 U per L; normal range: zero to 88 U per L. The serum lipase value was 575 U per L. Calcium, glucose and triglyceride levels were determined to be normal.

The child was admitted to the hospital and treated with intravenous fluids. Nasogastric suction was required to manage persistent vomiting. An abdominal sonogram the next day suggested pancreatic calcifications, and biliary sludge was noted in the gallbladder. Recurrent episodes of vomiting after the abdominal tenderness had resolved were attributed to gastroparesis and responded to therapy with oral cisapride (Propulsid).

Outpatient endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed about one month later and showed changes consistent with chronic pancreatitis (Figures 1 and 2). Small biliary stones were seen in the bile drainage. The patient underwent an uneventful laparoscopic cholecystectomy but had another episode of pancreatitis one month later. Genetic testing for the R117H mutation of the trypsinogen gene was reported as heterozygously positive.

At the six-month follow-up examination, the patient, having followed a low-fat diet, reported having only two brief episodes of abdominal pain, both of which followed ingestion of high-fat foods. His calcium and triglyceride levels remained normal.

Etiology

Pancreatic enzyme activation may be triggered by injury to the acinar cells of the pancreas or by premature activation of proenzymes within the pancreatic ducts. Trauma, ischemia, toxin exposure and infection can all cause cellular injury, and each can serve as the initiating event. Physical obstruction, ERCP and metabolic disorders can also cause cellular injury.

In a study of 30 families with hereditary pancreatitis,2 it was reported that most of the subjects had a mutant form of trypsinogen in which the activated trypsin was less capable of being autodigested. This mutation is estimated to account for 85 percent of trypsinogen mutations that cause hereditary pancreatitis. Other inherited anatomic or biochemical abnormalities, such as pancreas divisum, have also been associated with hereditary pancreatitis.

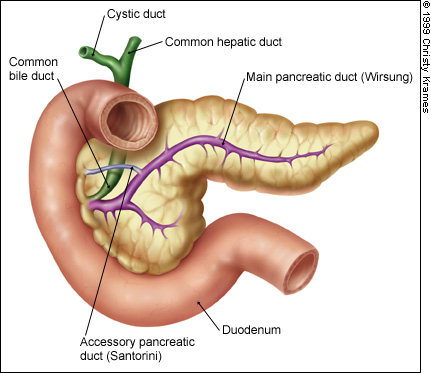

The normal anatomy of the pancreas is illustrated in Figure 3.

Trauma

The most common cause of pancreatitis in childhood and adolescence is blunt trauma, which accounts for 13 to 33 percent of cases.3 Elevated serum amylase levels are not diagnostic in trauma patients because of the possible coexistence of intestinal perforation. Child abuse should not be overlooked as a possible cause of the trauma.

Metabolic and Nutritional Causes

Hypercalcemia and hyperlipidemia are two recognized causes of pancreatitis, both in children and in adults. The hypercalcemia may be masked by the transient calcium-lowering effect of acute pancreatitis. Primary hyperparathyroidism related to adenoma or hyperplasia (sometimes secondary to multiple endocrine neoplasia, type IIa) is the most common cause of the hypercalcemia, followed by hyperparathyroidism secondary to chronic renal insufficiency.4

Diabetic or familial triglyceridemia, with serum triglyceride levels above 1,000 mg per dL, greatly increases the risk of pancreatitis. Patients undergoing dialysis are also at increased risk of developing pancreatitis, because about one half of them have hyperlipidemia.3 Worldwide, the most common type of recurrent pancreatitis in children is known variably as juvenile tropical pancreatitis or tropical calcific pancreatitis. Because this condition seems to cluster in geographic areas of certain tropical countries, dietary or environmental toxins are suspected.5

Alcohol and Drugs

Alcohol abuse is an uncommon cause of childhood pancreatitis but must be considered in the differential diagnosis, particularly in older adolescents. In adults, the ingestion of large quantities of alcohol seems to be necessary to produce pancreatitis.

Numerous medications have been weakly implicated as causes of pancreatitis. An increased frequency of the disease has been associated with use of chemotherapeutic agents such as asparaginase (Elspar) and azathioprine (Imuran), as well as the nucleoside analogs didanosine (Videx) and zalcitabine (Hivid), which are used in the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease.6 The association of valproic acid (Depakene) with pancreatitis is well recognized. Estrogens in oral contraceptives can raise plasma triglycerides to dangerous levels in some patients with type IV or type V hyperlipidemia.

Obstructive Causes

Gallstones are occasionally found in children with pancreatitis. Bile pigment stones resulting from hemolytic disease may occur in the prepubertal age group. Adolescent girls may develop cholesterol stones secondary to biliary stasis of pregnancy. It is important to realize that the presence of crystalline sludge or stones in the bile may be the result of stasis during acute attacks rather than the cause of the pancreatitis. Chronic pancreatitis itself, as well as concretions from cystic fibrosis, can obstruct pancreatic ductules. Inflammatory bowel disease may be associated with edema or fibrosis of the biliary tree.7

Pancreas divisum (in which the dorsal and ventral pancreatic ducts fail to fuse) is of uncertain significance, because it is present in 5 to 10 percent of the population. Other anatomic abnormalities include congenital choledochal cysts, sphincter abnormalities and annular pancreas. Parasites may theoretically obstruct the pancreatic ducts, but only the Ascaris species have been reported as a definite cause of pancreatitis.8

Infectious Causes

Strong evidence shows that direct pancreatic injury may be caused by a number of viruses, most notably mumps, coxsackie B, cytomegalovirus, varicella zoster and hepatitis B viruses. Other viral diseases, including hepatitis A and acute HIV infection, have been more weakly associated with pancreatic injury. Bacteria such as Salmonella and Mycoplasma have been implicated in a few cases of pancreatitis. Pancreatic infections with cytomegalovirus and hepatitis B occur primarily in adults with organ transplants.8

Systemic Causes

Hypotension and ischemia seem to be the causes of pancreatitis in shock or overdose states. Vasculitic diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus,9 Henoch-Schönlein purpura and (rarely) Kawasaki disease are also recognized causes of pancreatitis. In the past decade, Reye's syndrome has markedly decreased as a cause of pancreatitis as the use of aspirin in children has declined.

The conditions associated with childhood pancreatitis are listed in Table 1.

| Physical injury |

| Abdominal trauma (including child abuse) |

| Abdominal surgery |

| ERCP |

| Posterior penetrating duodenal ulcer |

| Multisystem disease |

| Crohn's disease |

| Hemolytic-uremic syndrome |

| Reye's syndrome |

| Sarcoidosis |

| Sepsis |

| Shock (hypoperfusion states) |

| Metabolic disorders |

| Hypercalcemia |

| Hyperlipidemia |

| Uremia |

| Drugs |

| Asparaginase (Elspar) |

| Azathioprine (Imuran) |

| Corticosteroids |

| Didanosine (Videx) |

| Estrogens |

| Ethacrynic acid (Edecrin) |

| Furosemide (Lasix) |

| Procainamide (Pronestyl) |

| Sulfasalazine (Azulfidine) |

| Sulfonamides |

| Tetracycline |

| Thiazides |

| Valproic acid (Depakene) |

| Zalcitabine (Hivid) |

| Toxins |

| Alcohol (ethanol/methanol) |

| Boric acid |

| Carbamates |

| Organophosphates |

| Yellow scorpion bite |

| Nutritional problems |

| Hyperalimentation-related |

| Malnutrition |

| Rapid refeeding after starvation |

| Infections |

| Campylobacter |

| Cryptosporidium |

| Leptospira |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae |

| Salmonella typhi |

| Toxoplasma |

| Viruses: mumps, CMV, HSV-2, coxsackie B, hepatitis B, VZV |

| Pancreatic disorders |

| Antitrypsin deficiency |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Pancreatis divisum |

| Pancreatic or ductal anomalies |

| Biliary tract obstruction |

| Biliary tract anomalies |

| Choledochal cyst |

| Duodenal obstruction |

| Gallstones |

| Parasites (Ascaris) |

| Vasculitis |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura |

| Kawasaki disease |

| Periarteritis nodosa |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus |

| Miscellaneous |

| Graft-versus-host disease |

| Hereditary |

| Idiopathic |

| Renal transplantation |

Clinical Presentation

Abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting is the hallmark of pancreatitis in children as well as in adults. It is characteristically a sharp, steady pain of sudden onset, commonly aggravated by eating and improved by drawing the knees up to the chest. The pain is generally epigastric, but it can also be located in the middle or even the lower abdomen, sometimes radiating to the back.10

On physical examination, the child usually appears anxious and uncomfortable, particularly with any movement. Tachycardia and fever are common; diffuse abdominal tenderness, more marked in the upper abdomen, and quiet bowel sounds are the rule. However, as demonstrated in the illustrative case, the diagnosis is not always obvious, and the symptoms can easily be attributed to gastroenteritis.

Other possible findings include signs of pancreatic ascites, an epigastric mass suggestive of pseudocyst formation, and bluish flanks (Grey Turner's sign) or umbilicus (Cullen's sign), indicating hemorrhagic pancreatitis. Evidence of pleural effusion or dyspnea in the presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome may be found on examination of the chest.

Laboratory Studies

Elevated white blood cell counts with increased band counts are usually present and do not, in themselves, imply infection. An increased hematocrit secondary to hemoconcentration that occurs after volume depletion may be found. Also, 15 percent of children with pancreatitis develop hypocalcemia, and up to 25 percent have hyperglycemia during the acute attack.

The serum amylase concentration is often, but not invariably, elevated. The value frequently becomes normal after two to five days. Urinary lipase levels may remain elevated for a few days longer than serum levels. The serum lipase level is also usually elevated, but the degree of elevation has little correlation with the extent of the pancreatitis. Levels of cationic trypsin are said to be a more sensitive early marker of pancreatic inflammation.10 Protracted elevations of serum amylase are suggestive of pseudocyst or other complications of pancreatitis.

Genetic testing for the predominant genetic mutation of hereditary pancreatitis is now available from the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center.2

Radiologic Findings

In cases of pancreatitis, sentinel loops, obscured psoas margins and a dilated duodenum may be seen on abdominal radiographs. One fifth of children show evidence of pleural effusion on chest films. The “colon cut-off” sign, in which a normal gas pattern is present only up to the mid-transverse colon, has also been described.

Ultrasound imaging is recommended to confirm the diagnosis as well as rule out obstructive anomalies. An enlarged, edematous-appearing pancreas suggests pancreatitis. A dilated main pancreatic duct indicates obstruction, and calcifications are often seen in older children with recurrent pancreatitis. Computed tomographic imaging is helpful in complicated cases, especially when surgery is being considered.

ERCP is generally not performed during the acute episode but is useful for finding surgically correctable ductal abnormalities. This procedure can also demonstrate the elevated intraductal pressures of functional or anatomic obstruction.

Treatment

The principles of therapy in adults are applicable to children and have been discussed in detail in a previous issue.11 The mainstays of supportive treatment are fluid resuscitation, pain medication and attention to nutritional needs. Fluid administration must be sufficient to replace “third spacing” and to maintain good urine output. In prolonged cases, peripheral or central intravenous nutrition may be necessary because of the high metabolic rate that accompanies pancreatitis. A low-fat elemental diet that is started early may decrease the need for total parenteral nutrition without aggravating the pancreatitis.12 Meperidine (Demerol) is preferred to morphine for pain control because it is less likely to cause spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, which can worsen the pancreatitis. Nasogastric suction is useful only when persistent vomiting or ileus is present. Antibiotics are generally unnecessary, even in the presence of elevated white blood cell counts and fever; they should be used only when infection is strongly suspected.

Children who have recurrent pancreatitis with intrapancreatic ductal strictures may need to undergo partial pancreatectomy or pancreaticojejunostomy for drainage. Biliary or duodenal obstructing lesions may require surgical correction. Endoscopic sphincterotomy with or without stone extraction, balloon dilation and stent placement may provide relief from frequent attacks of pancreatitis caused by obstruction.13 Although normal values for sphincter of Oddi manometry are poorly defined in children and infants, sphincterotomy or stenting may offer hope for patients with functional obstructions.14 A physician who is experienced in pediatric and adult therapeutic endoscopic pancreatic procedures must be involved in such an evaluation.

Prognosis

Acute uncomplicated cases of childhood pancreatitis have an excellent prognosis. Adult scoring systems such as the Ranson's prognostic signs and Apache II may be applicable, but their use in children has not been well evaluated. Marked elevations of glucose, lactate dehydrogenase and blood urea nitrogen levels, or falls in hematocrit, calcium, albumin or partial pressure of oxygen levels may also signify increased morbidity and mortality. The mortality rate is said to be about 10 percent in mild disease and up to 90 percent in rare cases of necrotizing or hemorrhagic pancreatitis.

Pseudocysts, which most often occur in trauma patients, develop two to three weeks after the acute episode. In children, they generally resolve spontaneously. Pancreatic phlegmon or abscess is rare in children but may require late drainage procedures.

Recurrent episodes of pancreatitis can lead to a chronic disease state. Chronic pancreatitis is a recognized risk factor for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. In a recent cohort study of 246 patients,15 the estimated cumulative risk of pancreatic cancer in patients up to age 70 with chronic pancreatitis was about 40 percent.