Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(3):873-880

See related patient information handout on gastroesophageal reflux disease, written by the authors of this article.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is the most common esophageal disease. Besides the typical presentation of heartburn and acid regurgitation, either alone or in combination, GERD can cause atypical symptoms. An estimated 20 to 60 percent of patients with GERD have head and neck symptoms without any appreciable heartburn. While the most common head and neck symptom is a globus sensation (a lump in the throat), the head and neck manifestations can be diverse and may be misleading in the initial work-up. Thus, a high index of suspicion is required. Laryngoscopy can confirm the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Erythema of the posterior larynx may be seen, and the true vocal cords may be edematous. Treatment should be initiated with a histamine H2 receptor blocker or proton pump inhibitor. Lifestyle changes are also beneficial. Untreated, GERD can lead to chronic laryngitis, dysphonia, chronic sore throat, chronic cough, constant throat clearing, granuloma of the true vocal cords and other problems.

Gastroesophageal reflux is defined as the movement of gastric contents into the esophagus without vomiting. Laryngopharyngeal reflux is the movement of gastric contents into the laryngopharyngeal area. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) occurs when gastric contents irritate mucosal surfaces of the upper aerodigestive tract.

Pathophysiology of GERD

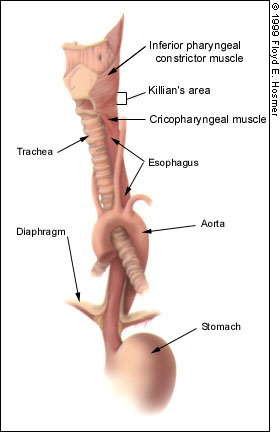

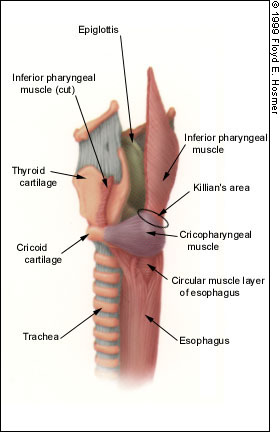

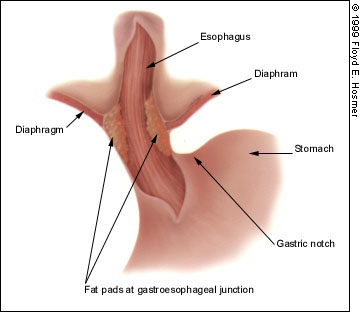

The primary barrier to gastroesophageal reflux is the lower esophageal sphincter, which is located at the level of the diaphragmatic hiatus and acts as the main deterrant to reflux1 (Figures 1a, 1b and 1c). Other structures that may be involved in preventing reflux are the intra-abdominal segment of the esophagus, the gastroesophageal angle, the diaphragmatic crura and the phrenoesophageal ligament. Gastric motility also plays a role, with delayed emptying predisposing the patient to GERD. The upper esophageal sphincter consists mainly of the cricopharyngeal muscle and a small portion of the circular muscle fibers of the esophagus immediately distal to it. The upper esophageal sphincter is referred to as the pharyngoesophageal junction and serves as the main barrier in preventing laryngopharyngeal reflux.

DIFFERENCES IN GASTROINTESTINAL AND HEAD AND NECK SYMPTOMS

The pathophysiology of GERD in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms differs from that in patients with head and neck symptoms. Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms have esophageal dysmotility and dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter, whereas patients with head and neck manifestations have dysfunction of the upper esophageal sphincter but good esophageal motility.2 Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms usually experience esophageal reflux when they are supine, whereas patients with head and neck manifestations have laryngopharyngeal reflux during the daytime when they are upright. Interestingly, one study revealed that only 18 percent of patients with head and neck manifestations of GERD had esophagitis.2

Heartburn, the classic symptom of GERD, is common in patients with gastrointestinal symptoms but uncommon in those with head and neck manifestations. One study3 reported only a 20 to 43 percent incidence of heartburn in patients with head and neck symptoms.

Diagnosis

The diagnostic work-up of patients presenting with symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux begins with a thorough history and a meticulous physical examination. Patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux present with symptoms related to the upper aerodigestive tract (Table 1). The most common symptom reported by patients is a “lump in the throat” (globus sensation). Studies3–5 have shown that in 23 to 60 percent of patients presenting with globus sensation, GERD is the etiologic factor.

| Aerophagia |

| Buccal burning |

| Cervical pain |

| Choking sensation |

| Chronic cough |

| Constant throat clearing |

| Dysphagia |

| Food sticking in throat |

| Globus sensation (the most common symptom) |

| Halitosis |

| Hoarseness (dysphonia) |

| Otalgia |

| Pharyngeal tightness |

| Sore throat |

| Water brash |

Other symptoms include constant throat clearing (caused by increased secretions and irritation of the laryngeal mucosa); dysphonia (caused by edema or inflammatory lesions of the true vocal cords); chronic sore throat (often misdiagnosed as recurrent or chronic tonsillitis); coughing; cervical dysphagia (caused by dysfunction of the upper esophageal sphincter); halitosis; buccal burning; otalgia (explained by the common sensory innervation of the esophagus and external auditory canal by the 10th cranial nerve); food sticking in the throat; pharyngeal tightness; a choking sensation; aerophagia; and water brash (hypersalivation). Laryngopharyngeal reflux should be suspected in patients who present with any of these symptoms.

Although oropharyngeal (cervical) dysphagia can result from GERD, other causes must be considered, especially if this symptom persists despite adequate treatment for GERD. Of course, this principle applies to all of the symptoms listed above, since they can also have other causes.

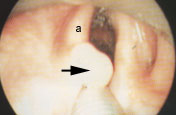

LARYNGOSCOPY

Indirect or direct laryngoscopy can be performed to confirm the diagnosis of GERD. Laryngoscopic findings suggestive of laryngopharyngeal reflux include the following: erythema of the arytenoid, interarytenoid area or laryngeal surface of the epiglottis; a cobblestone appearance of the interarytenoid area; edema of the true vocal cords; inflammatory lesions of the true vocal cords, such as granuloma and contact ulcer; and pooling of secretions in the hypopharynx (Figures 2, 3, 4a and 4b).

Edema of the true vocal cords can range from mild to severe; severe edema has the appearance of polypoid masses. Vocal cord edema of this degree can result in severe dysphonia, stridor or airway compromise. The edema develops in the superficial layer of the lamina propria of the true vocal cords, also called Reinke's space. Thus, it is often referred to as Reinke's edema. The presence of edema of the true vocal cords is highly suggestive of laryngopharyngeal reflux, even in the absence of laryngeal erythema.2

EMPIRIC THERAPY AND ADDITIONAL STUDIES

If the history and physical examination fail to uncover serious pathology, patients with suspected GERD may begin empiric therapy, which consists mainly of lifestyle modifications and drug therapy (Tables 26 and 3). Further evaluation is required if patients do not respond to empiric therapy or if they present with recurrent GERD or its complications. Surgical intervention may be required in such patients.

| Avoid fatty foods, caffeinated beverages (colas, coffee, etc.), chocolate, mint, spicy foods, tomato-based foods, garlic and onions |

| Stop smoking |

| Stop or decrease alcohol use |

| Lose weight if overweight |

| Elevate the head of the bed by placing 4- to 8-inch blocks under the bed posts at the head of the bed (adding additional pillows is insufficient) |

| Eat smaller meals |

| Avoid wearing tight-fitting clothes |

| Avoid eating within four hours of bedtime |

| Avoid recumbency within three hours of meals |

| Avoid medications that decrease the lower esophageal sphincter pressure (theophylline, anticholinergic agents, alpha-adrenergic antagonists, beta-adrenergic agonists, calcium channel blockers, nitrates)6 |

Further work-up may include an esophagram, manometry, endoscopy, a modified Berstein's test or ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring. The gold standard for making the diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux is dual-probe 24-hour pH monitoring, where the probes are placed in the pharynx and esophagus.2 This procedure has increased our understanding of the pathophysiology of GERD-related otolaryngologic complications.

Illustrative Cases

The following two cases illustrate the clinical presentations of GERD in patients with head and neck symptoms. The first case demonstrates a typical patient with laryngopharyngeal reflux manifested by a globus sensation and emphasizes the need for a thorough history and physical examination, including laryngoscopy. The second case demonstrates a laryngeal complication of GERD.

CASE 1

A 23-year-old woman was referred to an otolaryngologist because of the sensation of a lump in her throat. Further questioning revealed that she had intermittant dysphonia, otalgia and a dry cough. She denied heartburn but stated that her symptoms worsened when she ate spicy foods or drank coffee.

Laryngoscopy revealed erythema of the arytenoids, the interarytenoid area and the laryngeal surface of the epiglottis, along with mild edema of the true vocal cords. Laryngopharyngeal reflux was diagnosed, and treatment with omeprazole and antacids was initiated. The patient also received instructions about lifestyle modifications.

Reevaluation eight weeks later revealed complete resolution of her symptoms, and laryngoscopy demonstrated resolution of the laryngeal pathology. The omeprazole was replaced with a histamine H2 receptor antagonist, and the patient continued with the lifestyle modifications. She continues to do well.

CASE 2

A 37-year-old man was referred to an otolaryngologist because of the development of dysphonia, constant throat clearing, a globus sensation and a dry cough. Questioning revealed a history of vocal abuse. Past surgical history was significant for an excision of a granuloma on the left true vocal cord.

Laryngoscopy revealed endolaryngeal erythema and a large granuloma of the left true vocal cord (Figures 4a and 4b). Antireflux therapy (omeprazole, an antacid and lifestyle modifications) was started, and the patient was given instructions in voice care and use of an oral steroid inhaler.

Reevaluation after two months revealed resolution of all symptoms except dysphonia. Laryngoscopy demonstrated persistence of the left true vocal cord granuloma. Informed consent was obtained, and the patient was taken to the operating room for direct microlaryngoscopy with excision of the granuloma and injection of 10 units of botulinum toxin type A (Botox) into the left true vocal cord to weaken it, preventing repeated trauma to the surgical site. The effects of the botulinum toxin lasted four months. At the nine-month follow-up, the patient remained free of symptoms, without any evidence of the granuloma and with normal motion of both true vocal cords.

Complications

The complications of GERD can be divided into four categories: laryngeal, pharyngeal, esophageal and pulmonary.

LARYNGEAL

The laryngeal complications associated with GERD include the following: posterior laryngitis; cricoarytenoid joint fixation; laryngomalacia; functional voice disorders; posterior glottic stenosis; laryngospasm; chronic nonspecific laryngitis; Reinke's edema, contact ulcer, contact granuloma, leukoplakia and carcinoma of the true vocal cords; and subglottic stenosis.2,3,7–12

Contact granulomas arise from the vocal process (cartilaginous posterior portion) of the true vocal cords and are considered an inflammatory response from injury to the underlying perichondrium. In addition to antireflux therapy, botulinum toxin injection is used in the treatment of true vocal cord granulomas.13 Botulinum toxin paralyzes the true vocal cord, preventing forceful closure of the arytenoids during phonation and coughing, which allows the traumatized site to heal.

Antireflux surgery may be a consideration in patients with chronic symptoms that do not respond to adequate medical therapy. In one study10 of patients with GERD and laryngeal disease, 82 percent of the patients had resolution of laryngeal symptoms and normalization of laryngoscopic findings by six months or more after antireflux surgery. Patients in this study had GERD documented by 24-hour pH monitoring and laryngoscopic evidence of laryngeal pathology. They were referred for surgical therapy (Nissen fundoplication) because of an unsatisfactory response to medical therapy.

GERD has also been implicated in the development of leukoplakia and squamous cell carcinoma of the true vocal cords.3,10,11 Leukoplakia, defined as the presence of a whitish plaque on a mucosal surface, in itself does not carry any diagnostic implications. However, in the presence of GERD, leukoplakia is considered to be precancerous. In the study mentioned above, five patients with GERD were found to have laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma and underwent either surgical or radiation therapy; edema and leukoplakia persisted after treatment.10 All patients subsequently underwent antireflux surgery, and the laryngeal abnormalities resolved in three of four patients. (The fifth patient was lost to follow-up.) The findings suggest that premalignant lesions may be associated with GERD and may resolve after appropriate antireflux therapy. Although some evidence suggests that GERD is a cofactor in the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the larynx, research is needed to determine the importance of GERD in the pathogenesis.

PHARYNGEAL

The pharyngeal complications of GERD include cricopharyngeal dysfunction, chronic pharyngitis and Zenker's (pharyngeal) diverticulum.3,15–17 Zenker's diverticulum is a posterior pulsion pseudodiverticulum that arises from Killian's area (Figure 5). This area is located posterior to and bounded superiorly by the cricopharyngeal muscle and inferiorly by the inferior pharyngeal muscle. Because of the inherent muscle weakness in this area, it is predisposed to the development of Zenker's diverticulum.

Zenker's diverticulum results from increased intraluminal pressure caused by cricopharyngeal muscle spasm, which has been linked to gastroesophageal reflux.3 Regurgitation of partially digested food should alert the clinician to the possibility of a Zenker's diverticulum. A small asymptomatic Zenker's diverticulum can be managed with observation. Surgical therapy is reserved for patients with a large or symptomatic diverticulum.

ESOPHAGEAL

The esophageal complications of GERD include esophagitis, esophageal webs and strictures, Barrett's esophagus and carcinoma.18,19 Barrett's esophagus is defined as metaplasia of squamous epithelium to specialized columnar epithelium, occurring 2 to 3 cm above the gastroesophageal junction. However, short-segment (less than 2 cm) Barrett's esophagus has also been described.6 Barrett's esophagus is an endoscopic diagnosis and is associated with an increased incidence of adenocarcinoma.

PULMONARY

In a series of 72 children with chronic cough and normal findings on chest radiographs, GERD was implicated as the cause of symptoms in 15 percent of the patients.24 In another study of children, 24-hour pharyngeal pH monitoring established the role of GERD as an etiologic agent in recurrent laryngotracheitis (croup).23 In a series of 30 children who had an apparent life-threatening event (the infant was found limp, cyanotic, bradycardic or required resuscitation), GERD appeared to be the causative factor in 53 percent of the patients.21