Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(9):2543-2552

This is the first of a two-part article on the management of angina. Part II, “Medical Management,” will be published in the next issue.

Ischemic heart disease is one of the most common disorders managed by family physicians. Stratifying patients according to risk is important early in the course of the disease to identify patients who require invasive (percutaneous or surgical) treatment. Physical examination, clinical history, noninvasive tests and angiography are all helpful in determining who will benefit most from medical therapy, percutaneous revascularization or coronary artery bypass surgery. Surgery improves morbidity and mortality in a well-defined group of patients with left ventricular dysfunction and left main coronary artery disease or triple-vessel disease. Patients with proximal left anterior descending artery disease and moderate or severe ischemia benefit from surgery as well. In all other patients, definitive treatment includes aspirin, beta-adrenergic blockers and lipid-lowering agents. Percutaneous revascularization should be considered primarily a palliative measure, because it has never been shown to improve mortality more than medical therapy.

Despite a decline in mortality from cardiovascular disease, it remains the leading cause of death in the United States. Moreover, the morbidity and socioeconomic consequences of coronary heart disease will be accentuated in future years by the growing numbers of elderly persons in the U.S. population and the increased frequency of ischemic heart disease in the elderly. New diagnostic techniques allow earlier diagnosis of coronary artery disease, and noninvasive and invasive therapies provide an opportunity for earlier management of this disease. Chronic stable angina, a manifestation of coronary artery disease, can represent increased morbidity and mortality from the disease. It is generally accepted that coronary revascularization alleviates anginal symptoms and, in specific subgroups, improves mortality as well.

Our understanding of the impact of coronary artery bypass surgery on survival among patients with coronary artery disease is derived primarily from a database of five large studies dating from the 1970s (reviewed in Gersh, et al.,1 and Weiner2). Despite the many advances in the management of coronary artery disease that have occurred since the 1970s, the consistent conclusions of these studies remain undisputed today. The major survival benefit of surgical revascularization compared with medical therapy is in “sicker” patients, as defined by the extent of coronary artery disease, the presence of left ventricular dysfunction and the severity of angina or ischemia.1,3

Advances in percutaneous revascularization, such as stents and multivessel percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty, and improvements in adjuvant antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy, coupled with aggressive reduction of cardiovascular risk factors, now allow an alternative to coronary artery bypass surgery in many patients. Family physicians need to know the many criteria that identify patients at high and low risk of myocardial infarction and death so that high-risk patients can be appropriately referred for early surgical treatment and low-risk patients can be safely and appropriately treated medically.

Risk stratification depends primarily on three variables: the amount of jeopardized myocardium (the extent of ischemia), the amount of irreversibly necrotic myocardium (reflected by left ventricular function) and the number of diseased vessels. With the exception of the last piece of information, this information can be obtained from the history, the physical examination and cardiovascular testing.

Clinical Assessment of Risk

The history should include a rigorous assessment of the quality and quantity of angina. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) has developed a system of classifying the severity of angina (Table 1). The importance of such an objective classification lies in facilitating comparisons from one visit to the next. Data from the registry at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., indicate that the “tempo” of angina, defined by the frequency, stability and severity of angina over time, is an important factor in predicting subsequent cardiac events (that is, nonfatal myocardial infarction and death).2

| Class I — Angina only with unusually strenuous activity |

| Class II — Angina with slightly more prolonged or slightly more vigorous activity than usual |

| Class III — Angina with usual daily activity |

| Class IV — Angina at rest |

Patients who develop progressive anginal symptoms generally fare better with surgical treatment than with medical treatment. Thus, a progression from one stage to the next or any increase in the frequency of angina should alert the physician to the need for more aggressive evaluation, with a view toward possible coronary revascularization. Left ventricular function stands out as one of the most important predictors of survival; the need to probe carefully for signs or symptoms of congestive heart failure cannot be overemphasized4–10 (Table 2).

| Clinical history |

| Orthopnea |

| Dyspnea on exertion |

| Lower extremity edema |

| Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea |

| Pulmonary edema |

| Fatigue |

| Physical examination |

| S3 gallop |

| Rales |

| Paradoxically split S2 (without left bundle branch block) |

| Diffuse apical impulse |

| Elevated jugular venous pressure |

| Peripheral edema |

| Electrocardiogram |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy |

| Left bundle branch block |

| Chest radiograph |

| Enlarged cardiac silhouette |

Age is also a predictive indicator. Compared with younger patients treated medically, elderly patients have a poorer prognosis with medical treatment. Although advanced age increases the morbidity and mortality associated with coronary revascularization procedures, the survival rate of elderly patients treated medically is also reduced. As such, they comprise a subgroup in whom the relative survival benefits of coronary revascularization over medical therapy are particularly increased.

While clinical assessment allows classification of the patient according to a high, intermediate or low risk of cardiac events (Table 3), the findings from the history and physical examination can be misleading. Systolic function can be severely impaired despite a lack of symptoms, and ischemia can be asymptomatic, making clinical assessment of the amount of scarred and jeopardized myocardium difficult. Many patients benefit from further noninvasive testing. A stress test (and an echocardiogram when it is indicated) is more sensitive, specific and objective than the history and physical examination and can aid in the risk-stratification process.

| Low risk | High risk |

|---|---|

| Stable angina | Unstable angina |

| No congestive heart failure | Congestive heart failure |

| Normal findings on resting ECG | Q waves or ischemic ST-T wave changes on resting ECG |

| Normal left ventricular function | Markedly depressed systolic function |

Contraindications to exercise stress testing should be clarified during the history and physical examination (Table 4), and the choice of exercise stress testing versus pharmacologic testing should be determined. Cardiac catheterization should be considered in patients in whom any type of stress test is deemed too risky.

| Consider pharmacologic stress test under the following circumstances: |

| Acute thrombophlebitis or deep venous thrombosis |

| Neuromuscular, musculoskeletal or arthritic condition that precludes treadmill exercise |

| Patient's inability or lack of desire to perform the test |

| Easy fatigability |

| Consider cardiac catheterization under the following circumstances: |

| Recent (within 6 days) acute myocardial infarction |

| Angina at rest |

| Severe symptomatic left ventricular dysfunction |

| Potentially life-threatening arrhythmias |

| Acute pericarditis, myocarditis or endocarditits |

| Severe aortic stenosis |

| Acute pulmonary infarct or embolus |

| Acute or serious general illness |

Noninvasive Testing

An algorithm for the evaluation of patients with chronic stable angina is given in Figure 1.

ELECTROCARDIOGRAM

A routine electrocardiogram (ECG) may provide prognostic information. Pathologic Q waves indicative of an old myocardial infarction,2 resting ST-T wave changes2 and evidence of an intraventricular conduction delay4 are associated with a poor prognosis in patients with underlying coronary artery disease. However, ECG abnormalities can be caused by many noncardiac entities, such as electrolyte abnormalities, pulmonary disease and certain drugs, thus decreasing the specificity of abnormal findings. Therefore, risk stratification cannot be entirely based on abnormal findings on a resting ECG but, in the appropriate clinical setting, the ECG findings can point to a need for further risk stratification.

ECHOCARDIOGRAM OR VENTRICULOGRAM TO ASSESS LEFT VENTRICULAR FUNCTION

Impaired ejection fraction identifies the patient at increased risk for myocardial infarction and death regardless of whether coronary revascularization is performed or drug therapy is initiated. Nonetheless, the diagnosis of left ventricular dysfunction opens a window of opportunity to improve the patient's outcome. It is well established that the relative survival benefit of coronary revascularization over medical therapy is greatest in patients with a combination of left ventricular dysfunction and three-vessel or left main coronary artery disease. A review of data from the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS) demonstrated that ejection fraction correlates directly with survival in a continuous fashion; patients with the lowest ejection fraction benefit the most from surgical revascularization.1

While the clinical history, physical examination, ECG and chest radiograph are extremely helpful in disclosing the presence of left ventricular dysfunction, objective assessment by echocardiogram or left ventriculogram clarifies the extent of disease, offers prognostic information and determines the potential benefit of surgical revascularization. An echocardiogram is not required for everyone, however. Patients without signs or symptoms suggestive of congestive heart failure and those who are deemed at low risk and are not being considered for revascularization are unlikely to benefit from the information in an echocardiogram.

On the other hand, objective assessment of left ventricular function is warranted in patients with a history consistent with congestive heart failure and in patients with moderate to severe angina in whom a revascularization procedure is being considered. Objective evaluation of left ventricular function is also warranted when the prognosis needs to be further clarified. Identification of ischemia in the region of the wall motion abnormality is of particular importance, because the ischemia is a potentially reversible cause of left ventricular dysfunction. The presence of ischemia can be identified on a cardiac stress test.

TREADMILL EXERCISE TEST

Although the sensitivity and specificity of treadmill exercise testing in diagnosing coronary artery disease are only 65 to 80 percent,11 exercise testing still contributes significantly to the identification of patients with coronary artery disease who would benefit from cardiac catheterization (Table 5). In patients with known coronary artery disease, the purpose of an exercise stress test is to help clarify the severity of coronary artery obstruction and, in so doing, better define the patient's prognosis. Patients with large areas of underperfused but viable myocardium are most likely to benefit from revascularization.

| Exercise duration < 5 METs | |

| ST-segment depression | |

| Magnitude (≥ 2 mm) | |

| Time of onset (stage I or II) | |

| Duration (> 5 minutes) | |

| Number of leads (≥ 5) | |

| Blood pressure | |

| Low (< 130 mm Hg) peak systolic blood pressure | |

| Decrease of systolic blood pressure to below the resting standing blood pressure | |

| Inability to attain target heart rate* | |

| Presence of exercise-induced angina | |

| Ventricular ectopy (couplets or tachycardia) at low workload | |

Exercise duration is one of the strongest independent prognostic indicators and correlates directly with outcome.2 Patients in the Duke University registry who were able to enter stage IV of the exercise protocol had excellent long-term survival. The annual mortality rate over two years of follow-up was 2 percent in this group, compared with a 10 percent annual mortality rate in patients with a positive test in stages I or II.2 Even in patients with ischemia, the longer the exercise duration, the better the prognosis.

Analysis of the CASS database demonstrates that patients with ischemic ST-segment depression who enter stages III, IV or V of a Bruce protocol have a significantly better survival rate than patients with the same degree of ST depression who are unable to complete stage I.8 Equally as important, patients categorized as low risk on the basis of treadmill testing have an excellent survival rate, even in the presence of multivessel disease.7 Patients in the CASS registry with triple-vessel disease who achieved stage V had a zero percent annual mortality rate, compared with a mortality rate of 12 percent in those who were unable to complete stage I.

Finally, patients with triple-vessel disease who were stratified into the high-risk category on the basis of treadmill results alone demonstrated a significant survival benefit from surgery compared with medical therapy (81 percent versus 58 percent), whereas those in the low-risk group experienced an excellent survival rate regardless of the treatment modality (88 percent with surgery and 83 percent with medical therapy).8

The role of “silent ischemia” detected on a treadmill exercise test or an ambulatory ECG is controversial. Some authorities suggest that brief repetitive bouts of myocardial ischemia induce collateralization of the ischemic area and in this way are ultimately protective.12 Other evidence suggests that asymptomatic ischemia is detrimental because it causes small areas of patchy necrosis.13 Epidemiologic evidence does not elucidate the predictive value of silent ischemia, with some studies suggesting that patients with silent ischemia have a lower risk of myocardial infarction and death than those with symptomatic ischemia14 and other studies implying they have a higher risk.15 These varied results are largely due to the differences in the patient populations studied, as well as the test (ambulatory monitoring, stress test, etc.) used to detect silent ischemia. The final word on the predictive value of “silent” ST changes on an exercise stress test or ambulatory ECG is pending.

The treadmill stress test yields independent prognostic information that aids in the identification of a subgroup of high-risk patients whose survival could be improved with surgical treatment. However, many patients are either unable to exercise adequately or have abnormal findings on the baseline ECG and, thus, lack the prerequisites necessary for a clinically meaningful ECG stress test. Degenerative joint disease, pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, disorders of the central nervous system or poor general conditioning may interfere with the patient's ability to achieve a target heart rate, defined as 85 percent of the maximum predicted heart rate based on the patient's age (220 minus the patient's age). Such patients should undergo pharmacologic stress testing using dipyridamole (Persantine), adenosine (Adenoscan) or dobutamine (Dobutrex). Resting ECG abnormalities, such as left bundle branch block, left ventricular hypertrophy with repolarization abnormalities or ST-T wave abnormalities, markedly reduce the specificity of the stress ECG and mandate the use of a nuclear or echocardiographic stress study. As mentioned previously, cardiac catheterization should be considered in patients with contraindications to stress tests.

NUCLEAR STRESS TEST

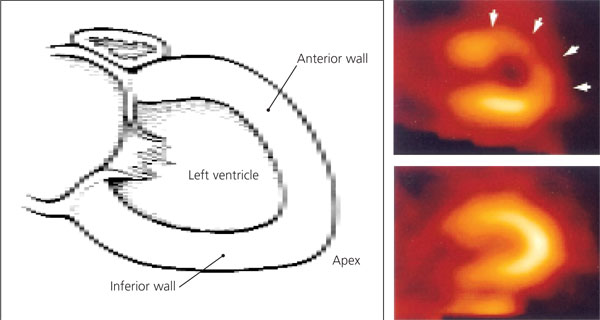

Interpretation of nuclear perfusion studies is based on inhomogeneity of the distribution of the tracer due to differences in myocardial blood flow (Figure 2). Scarred myocardium that receives no blood flow appears as a “cold” spot on the resting and stress images. Ischemic myocardium appears normal on the resting images but is underperfused during exercise and therefore appears less bright on the cardiac stress images (Figure 3). For patients who are able to exercise, the performance of exercise in addition to perfusion scintigraphy provides added prognostic information. Nonetheless, for the patient who is unable to walk on a treadmill, the sensitivity and specificity of pharmacologically induced stress (with dobutamine, adenosine or dipyridamole) are similar to the sensitivity and specificity obtained with exercise perfusion imaging.

A one-year follow-up study of patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease suggests that the number of thallium scintigraphic perfusion defects is the strongest predictor of the risk of nonfatal myocardial infarction and death.16 Other findings on nuclear studies also correlate with outcome (Table 6). It is important to note that because nuclear studies are based on blood flow differential, a heart with diffuse coronary artery disease may have uniformly diffusely reduced blood flow during exercise and appear homogenous on thallium scintigraphs. These scans may incorrectly be interpreted as normal.

| Number of defects (reversible and irreversible) |

| Severity of hypoperfusion (mild, moderate, severe) |

| Elevated ratio of lung–heart thallium uptake |

| Exercise-induced dilatation of the left ventricle |

STRESS ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

Stress echocardiography is an alternative imaging modality that can be used in place of nuclear testing in patients who do not meet the criteria for an adequate treadmill ECG test. With the use of ultrasound waves to visualize the myocardium, wall motion abnormalities and wall thickening can be detected. During stress-induced ischemia, decrements in contractile function are directly related to decreases in regional subendocardial blood flow. Physiologically, wall motion changes precede ischemic ECG changes, accounting for the greater sensitivity of an echocardiographic stress test compared with an ECG stress test.

Pharmacologic agents can be used to induce stress as well. Dobutamine stress echocardiography has a sensitivity and specificity of approximately 85 percent, comparable to that of pharmacologic radionuclide scintigraphic stress tests.17 Because their mode of action is different from that of dobutamine, adenosine and dipyridamole are less sensitive and are not commonly used in stress echocardiography. Studies are under way to further characterize the potential application of these two agents in stress echocardiography. Echocardiography is limited primarily by the ability of the technician to acquire clear pictures rapidly and by the patient's body habitus, pulmonary anatomy and acoustic windows.

Therapeutic Decisions

Data acquired from the patient's history, physical examination, ECG, echocardiogram and stress test enable adequate evaluation of the degree of left ventricular dysfunction and the extent of angina and ischemia. The patient's risk of myocardial infarction and death can be assessed, and a decision to refer the patient for further invasive work-up can be made. In patients undergoing cardiac catheterization, once the number and severity of diseased vessels are known, the optimal treatment can be determined.

Weighing the risks and benefits of coronary artery bypass graft surgery versus angioplasty and other percutaneous techniques can be a difficult process. The American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) have developed recommendations to aid with this decision.18 These guidelines revolve around the severity of symptoms, the degree of left ventricular dysfunction, the number of diseased vessels and the results of the stress test. In patients with chronic stable angina (NYHA classes I and II), coronary artery bypass surgery is recommended for those with left main coronary artery disease or severe disease of the proximal left anterior descending artery (regardless of systolic function or stress test results) and for those who have three-vessel disease and demonstrate moderate to severe left ventricular dysfunction or moderate to severe myocardial ischemia.

A recent meta-analysis19 of randomized trials comparing medical therapy with coronary artery bypass surgery demonstrated a significant mortality benefit with surgery in patients with three-vessel disease regardless of systolic function. Consistent with this finding, the ACC/AHA guidelines note that surgery is an acceptable option in all patients with three-vessel disease.18 In patients whose symptoms are more severe (NYHA angina class III or IV), especially with objective evidence of significant ischemia or left ventricular dysfunction, surgery should be considered regardless of the number of diseased vessels, with the understanding that its purpose may not be prolongation of survival but rather palliation of symptoms. At the other extreme, patients who have single-vessel disease (with the exception of disease of the left main coronary artery or severe narrowing of the proximal left anterior descending artery), functional class I or II angina, mild ischemia or mild left ventricular dysfunction show no benefit from surgery compared with medical therapy, and coronary bypass surgery is not appropriate (unless medical therapy or coronary angioplasty fails to control their symptoms). Patients for whom surgery has not been shown to be beneficial clearly benefit from medical therapy, including aspirin, beta-adrenergic blockers and lipid-lowering drugs (drug therapy will be discussed in the second part of this article).

Studies comparing coronary angioplasty and bypass grafting have, overall, failed to show any significant difference in the mortality and infarction rates for up to five years after the procedure.20–23 The only exception is a subgroup analysis of the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigators (BARI) study,24 which concluded that diabetic patients with two-vessel disease (a category of disease not previously shown to benefit from surgery) have a significantly improved five-year survival rate after bypass surgery compared with that following coronary angioplasty and medical treatment. Newer percutaneous techniques (heparin-coated stents, irradiated stents and other devices), along with more complete percutaneous revascularization (using platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors and other drugs), have yet to be compared with coronary artery bypass surgery. How these advances will affect the outcome of percutaneous interventions is still unknown.

No study to date has shown a mortality benefit of coronary angioplasty versus medical therapy. However, angioplasty has been shown to provide more complete relief of angina and to improve exercise performance during short-term (six-month) follow-up.25 In the Medicine, Angioplasty or Surgery Study (MASS),26 three-year follow-up of patients with proximal left anterior descending artery disease revealed similar results with respect to abolishing limiting angina in patients treated with coronary angioplasty or medical therapy. Both groups had equally low rates of death or myocardial infarction. Whether newer percutaneous techniques can extend the short-term benefits observed with coronary angioplasty remains to be seen.

Final Comment

One of our goals is to identify patients who have triple-vessel disease or left main coronary artery disease and patients who have proximal left anterior descending artery disease and moderate to severe ischemia, because these subgroups have been shown to benefit from surgical revascularization. Patients with any of the above-mentioned findings and a depressed ejection fraction are at particularly high risk of death and derive all the more benefit from coronary artery bypass surgery. Identification of patients at high risk of death depends on the history, the physical examination and noninvasive test results.

The optimal treatment for patients falling into the intermediate-risk category is less clear. It must be emphasized that percutaneous revascularization provides mainly palliative effects. It does not prevent myocardial infarction nor does it decrease mortality from the disease. Mortality in high-risk patients is decreased by bypass surgery. In addition, medical therapy, including aspirin, beta blockers and lipid-lowering agents, has been shown to prevent myocardial infarction and to improve survival and should be considered the definitive treatment for all patients with coronary artery disease.