Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(5):1319-1328

Although heart failure is a common clinical syndrome, especially in the elderly, its diagnosis is often missed. A detailed clinical history is crucial and should address not only current signs and symptoms of heart failure but also signs and symptoms that point to a specific cause of the syndrome, such as coronary artery disease, hypertension or valvular heart disease. It is important to determine whether the patient has had a previous cardiac event, in particular a myocardial infarction. The physical examination should include Valsalva's maneuver, a test that is highly specific and sensitive for the detection of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with heart failure. An electrocardiograph and a chest radiograph should also be obtained. Two-dimensional echocardiography of the heart helps differentiate systolic from diastolic dysfunction. Coronary angiography is indicated in patients with heart failure and anginal chest pain and should be strongly considered in patients with an electrocardiogram suggestive of ischemia or myocardial infarction.

Heart failure affects an estimated 4.9 million Americans,1 or 1 percent of adults 50 to 60 years of age and 10 percent of adults in their 80s.2 Each year, about 400,000 new cases of heart failure are diagnosed in the United States.1 This clinical syndrome is the most frequent cause of hospitalizations in the elderly and is responsible for 5 to 10 percent of all hospital admissions.1 Heart failure causes or contributes to approximately 250,000 deaths every year.3

The clinical syndrome of heart failure manifests when cellular respiration becomes impaired because the heart cannot pump enough blood to support the metabolic demands of the body, or when normal cellular respiration can only be maintained with an elevated left ventricular filling pressure.4

The Framingham,5 Duke6 and Boston7 criteria were established before noninvasive techniques for assessing systolic and diastolic dysfunction became widely available. The three sets of criteria were designed to assist in the diagnosis of heart failure. The Boston criteria (Table 1)8 have been shown to have the highest combined sensitivity (50 percent) and specificity (78 percent ). All of these criteria are most helpful in diagnosing advanced or severe heart failure, a condition that occurs in 20 to 40 percent of patients with a decreased ejection fraction.9

Early diagnosis of heart failure is essential for successfully addressing underlying diseases or causes and, in some patients, preventing further myocardial dysfunction and clinical deterioration. However, initial diagnosis may be difficult because the presentations of heart failure can change from no symptoms to pulmonary edema with cardiogenic shock. It is estimated that heart failure is correctly diagnosed initially in only 50 percent of affected patients.10,11 A systematic approach can improve overall accuracy in diagnosing this condition.

History

The first step in diagnosing heart failure is to obtain a complete clinical history. The patient should be questioned about dyspnea, cough, nocturia, generalized fatigue and other signs and symptoms of heart failure.

Dyspnea, a cardinal symptom of a failing heart, often progresses from dyspnea on exertion to orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and dyspnea on rest. Cough, usually nocturnal and nonproductive, may accompany dyspnea and often occurs in similar settings (i.e., on exertion or when the patient is supine).

Nocturia, also a frequent sign of heart failure, occurs secondary to increased renal perfusion when the patient is supine.12 Generalized fatigue (caused by the low perfusion state) and peripheral edema with inability to wear usual footwear are frequent complaints.

As heart failure progresses, gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g., abdominal bloating, anorexia and fullness in the right upper quadrant) are occasionally seen. With severe, longstanding heart failure, cardiac cachexia (emaciation resulting from heart disease) may develop secondary to protein-losing enteropathy and increased levels of certain cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor. Cardiac cachexia may mimic the cachexia seen in patients with disseminated malignant disease.

Confusion and altered mental status may occur because of decreased cerebral perfusion or cardiac cirrhosis. In heart failure, cirrhosis develops secondary to chronic passive congestion of the liver.

The patient should be asked about previous chest pain or myocardial infarction because coronary artery disease is responsible for up to 75 percent of cases of heart failure with decreased left ventricular function.13 A history of myocardial infarction has a better combination of sensitivity, specificity and positive and negative predictive value for heart failure compared with other symptoms or aspects of the medical history.14

It is important to identify a history of hypertension, in that high blood pressure is the second most frequent cause of heart failure. Information about other possible causes of heart failure should also be sought (Table 2).

| Most common causes |

| Coronary artery disease |

| Hypertension |

| Valvular heart disease (especially aortic and mitral disease) |

| Other causes |

| Infections: viruses (including human immunodeficiency virus), bacteria, parasites |

| Pericardial diseases |

| Drugs (e.g., doxorubicin [Adriamycin], cyclophosphamide [Cytoxan], cocaine) |

| Alcohol |

| Connective tissue disease |

| Infiltrative disease (e.g., amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, malignancy) |

| Tachycardia |

| Obstructive cardiomyopathy |

| Neuromuscular disease (e.g., muscular or myotonic dystrophy, Friedreich's ataxia) |

| Metabolic disorders (e.g., glycogen storage disease type 2 [Pompe's disease] and type 5 [McArdle's disease]) |

| Nutritional disorders (e.g., beriberi, kwashiorkor) |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Radiation |

| Endomyocardial fibrosis |

| Eosinophilic endomyocardial disease |

| High-output heart failure (e.g., intracardiac shunt, atrioventricular fistula, beriberi, pregnancy, Paget's disease, hyperthyroidism, anemia) |

| Peripartum cardiomyopathy |

| Dilated idiopathic cardiomyopathy |

Physical Examination

A complete physical examination is the second component in the diagnosis of heart failure. The patient's general appearance should be assessed for evidence of resting dyspnea, cyanosis and cachexia.

BLOOD PRESSURE AND HEART RATE

The patient's blood pressure and heart rate should be recorded. High, normal or low blood pressure may be present. The prognosis is worse for patients who present with a systolic blood pressure of less than 90 to 100 mm Hg when not receiving medication (angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors, beta blockers or duretics).16 Tachycardia may be a sign of heart failure, especially in the decompensated state. The heart rate increases as one of the compensatory ways of maintaining adequate cardiac output. A decrease in the resting heart rate with medical therapy can be used as a surrogate marker for treatment efficacy. A weak, thready pulse and pulsus alternans are associated with decreased left ventricular function. The patient should also be monitored for evidence of periodic breathing (Cheyne-Stokes respiration).

JUGULAR VENOUS DISTENTION

Jugular venous distention is assessed while the patient is supine with the upper body at a 45-degree angle from the horizontal plane. The top of the waveform of the internal jugular venous pulsation determines the height of the venous distention. An imaginary horizontal line (parallel to the floor) is then drawn from this level to above the sternal angle. A height of more than 4 to 5 cm from the sternal angle to this imaginary line is consistent with elevated venous pressure (Figure 1).

Elevated jugular venous pressure is a specific (90 percent) but not sensitive (30 percent) sign of elevated left ventricular filling. The reproducibility of the jugular venous distention assessment is low.17

POINT OF MAXIMAL IMPULSE

The point of maximal impulse of the left ventricle is usually located in the midclavicular line at the fifth intercostal space. With the patient in a sitting position, the physician uses fingertips to identify this point. Cardiomegaly usually displaces the cardiac impulse laterally and downward.

At times, the point of maximal impulse may be difficult to locate and therefore loses sensitivity (66 percent). Yet the location of this point remains a specific indicator (96 percent) for evaluating the size of the heart.14

THIRD AND FOURTH HEART SOUNDS

A double apical impulse can represent an auscultated third heart sound (S3). Just as with the displaced point of maximal impulse, a third heart sound is not sensitive (24 percent) for heart failure, but it is highly specific (99 percent).14 Patients with heart failure and left ventricular hypertrophy can also have a fourth heart sound (S4). The physician should be alert for murmurs, which can provide information about the cause of heart disease and also aid in the selection of therapy.

PULMONARY EXAMINATION

Physical examination of the lungs may reveal rales and pleural effusions. Despite the presence of pulmonary congestion, rales can be absent because of increased lymphatic drainage and compensatory changes in the perivascular structures that have occurred over time. Wheezing may be the sole manifestation of pulmonary congestion. Frequently, asthma is erroneously diagnosed in patients who actually have heart failure.

LIVER SIZE AND HEPATOJUGULAR REFLUX

The key component of the abdominal examination is the evaluation of liver size. Hepatomegaly may occur because of right-sided heart failure and venous congestion.

The hepatojugular reflux can be a useful test in patients with right-sided heart failure. This test should be performed while the patient is lying down with the upper body at a 45-degree angle from the horizontal plane. The patient keeps the mouth open and breathes normally to prevent Valsalva's maneuver, which can give a false-positive test. Moderate pressure is then applied over the middle of the abdomen for 30 to 60 seconds. Hepatojugular reflux occurs if the height of the neck veins increases by at least 3 cm and the increase is maintained throughout the compression period.18

LOWER EXTREMITY EDEMA

Lower extremity edema, a common sign of heart failure, is usually detected when the extracellular volume exceeds 5 L. The edema may be accompanied by stasis dermatitis, an often chronic, usually eczematous condition characterized by edema, hyperpigmentation and, commonly, ulceration.

VALSALVA'S MANEUVER

Valsalva's maneuver is rarely used in the evaluation of patients with heart failure. Yet this test is simple to perform and carries one of the best combinations of specificity (91 percent) and sensitivity (69 percent) for the detection of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction in patients with heart failure.19,20

Valsalva's maneuver is performed with the blood pressure cuff inflated 15 mm Hg over the systolic blood pressure. While the physician auscultates over the brachial artery, the patient is asked to perform a forced expiratory effort against a closed airway (the Valsalva's maneuver).

A normal response would be an initial rise in systolic blood pressure at the onset of straining (phase I) with Korotkoff's sounds heard (Figure 2). While the maneuver is maintained (phase II), a decrease in the blood pressure occurs with loss of Korotkoff's sounds. Release of the maneuver (phase III) is followed by an overshoot of blood pressure and the reappearance of heart sounds (phase IV). Abnormal responses occurring in patients with heart failure are maintenance of beats throughout Valsalva's maneuver (square wave) or lack of reappearance of Korotkoff's sounds after release of the maneuver (absent overshoot).

DIAGNOSTIC CHALLENGES

Diagnosing heart failure in elderly patients may be particularly challenging because of the atypical presentations in this age group. Anorexia, generalized weakness and fatigue are often the predominant symptoms of heart failure in geriatric patients. Mental disturbances and anxiety are also common.

When older persons become symptomatic on exertion, they decrease their level of activity to the point of becoming relatively asymptomatic. A cycle of symptoms on exertion and consequent decrease in activity frequently continues as the disease progresses, until the patient finally becomes symptomatic at rest (i.e., NYHA class IV).

The physical findings in older patients with heart failure may be difficult to interpret accurately. Resting tachycardia is uncommon, and pulse contour abnormalities are difficult to assess secondary to peripheral arteriosclerotic changes. At times, auscultatory findings on the lung examination are atypical because of concomitant pulmonary disease.21

Laboratory Findings

Most patients with heart failure have normal electrolyte levels. However, extended use of kaliuretic diuretics can lead to hypokalemia, and the use of potassium-sparing diuretics and ACE inhibitors may result in hyperkalemia. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels may become elevated, reflecting prerenal azotemia. Hyponatremia may be present in patients with advanced heart failure.

When the liver becomes congested, serum transaminase and bilirubin levels may become elevated, and jaundice may be present. With chronic congestive hepatomegaly, cardiac cirrhosis may occur and cause hypoalbuminemia, hypoglycemia and an increased prothrombin time.

The prognosis is worse in patients with hyponatremia or abnormalities secondary to congested hepatomegaly.

Anemia may contribute to worsening heart failure. When severe, anemia may even cause heart failure.

In all patients with newly diagnosed heart failure, thyroid function tests should be performed to rule out hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism.

It may soon be possible to routinely obtain serum measurements of two plasma enzymes secreted by the overloaded heart. Plasma atrial natriuretic peptide is secreted in response to increased intra-atrial pressure, and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) is secreted by the failing ventricle. Levels of these enzymes, but specifically BNP, are elevated in patients with dyspnea resulting from heart failure. In one study, elevated BNP levels had more than a 90 percent specificity and sensitivity for heart failure.22

Diagnostic Tests

ELECTROCARDIOGRAPHY

An electrocardiogram (ECG) should be obtained in all patients who present with heart failure. No specific ECG feature is indicative of heart failure, but atrial and ventricular arrhythmias are common findings. For example, atrial fibrillation is present in 25 percent of patients with cardiomyopathy, especially elderly patients with advanced heart failure.23 The prognosis is worse for patients with atrial fibrillation, atrial or ventricular tachycardia, or left bundle branch block.16,24

Low voltage on the ECG in association with conduction disturbances may suggest the presence of amyloidosis.

CHEST RADIOGRAPHY

Chest radiographs can be helpful in the diagnosis of heart failure. Cardiomegaly is usually manifested by the presence of an increased cardiothoracic ratio (greater than 0.50) on a posteroanterior view. However, patients with predominantly diastolic dysfunction may have normal heart size, one of the distinguishing markers of diastolic versus systolic dysfunction. Right ventricular enlargement is suggested by the loss of free space between the cardiac silhouette and the sternum on a lateral view.

Signs of increased pulmonary venous pressure seen on chest radiographs may progress from redistribution of blood flow from the bases of the lungs to the apices to linear densities reflecting interstitial edema (Kerley's lines) to a hazy appearance concentrated mostly around the hila of the mediastinum and presenting a butterfly pattern.

Chest radiographs are also helpful in detecting pleural effusion secondary to heart failure.

ECHOCARDIOGRAPHY

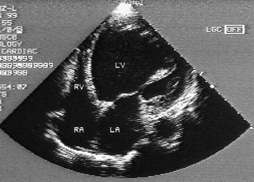

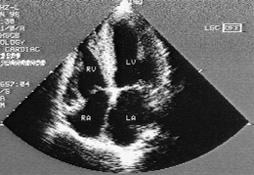

Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography with Doppler flow studies is highly recommended for all patients with heart failure.25 This test helps in the assessment of left ventricular size, mass and function.

Transesophageal echocardiography offers higher quality images than transthoracic studies. However, this technique is invasive and is best reserved for use when the quality of the two-dimensional echocardiogram is unacceptable.

ANGIOGRAPHY

Radionuclide angiography is another non-invasive method for assessing systolic and diastolic function. This imaging technique is used when two-dimensional echocardiography is not diagnostic because adequate images could not be obtained or the findings do not agree with the clinical picture. Radionuclide angiography provides a reliable and quantitative measurement of the left ventricular ejection fraction and the regional wall motion. However, ectopic activity and atrial fibrillation adversely affect the accuracy of its measurements.28

Left ventricular angiography can be used to assess the ejection fraction, the left ventricular volume and the severity of valvular regurgitation or stenosis. In addition, detailed measurements of ventricular filling pressures and indices of left ventricular diastolic relaxation rate can be helpful in confirming diastolic dysfunction.

OTHER TECHNIQUES

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)29 and ultrafast or cine computed tomography (CT)30 can measure the ejection fraction and assess regional wall motion. However, assessment of cardiac function using these studies is only performed in a limited number of centers, and the superiority of the studies to echocardiography and angiography has not been proved.

Sometimes coronary artery disease must be excluded as a causal factor in patients with heart failure. Cardiac catheterization and coronary angiography should be strongly considered in all patients with heart failure and angina who are candidates for interventional procedures. In patients with known coronary artery disease and heart failure but no angina, coronary arteriography or noninvasive testing (i.e., a thallium stress test or stress echocardiogram), followed by coronary arteriography in those patients with ischemia, should be considered. The intensity of the search for ischemic heart disease in patients with heart disease depends on the patient's probability of having coronary artery disease.

If imaging techniques cannot confirm the cause of cardiac dysfunction, an endomyocardial biopsy may provide important information in patients receiving cardiotoxic drugs and in patients suspected of having infectious (i.e., acute or chronic viral myocarditis), genetic or systemic diseases with possible cardiac involvement.25 However, the diagnostic yield of this procedure is typically less than 10 percent.31

Systolic vs. Diastolic Dysfunction

As many as 40 percent of patients with clinical heart failure have diastolic dysfunction with normal systolic function.32 In addition, many patients with systolic dysfunction have elements of diastolic dysfunction. With systolic dysfunction, the pumping ability of the ventricle is impaired. With diastolic dysfunction, ventricular filling is defective.

Ventricular diastolic function depends on the pressure-to-volume relationship in the left ventricle. Decreased compliance of the left ventricular wall leads to a higher pressure for a given diastolic volume. The end result is impaired ventricular filling, inappropriately elevated left atrial and pulmonary venous pressure, and decreased ability to increase stoke volume. These dysfunctions lead to the clinical syndrome of heart failure.

Findings suggestive of diastolic dysfunction on the two-dimensional echocardiogram are left ventricular hypertrophy, a dilated left atrium, a normal or nearly normal ejection fraction and reversal of the normal pattern of flow velocity (measured by Doppler flow studies) across the mitral valve (Figures 3 and 4).

Differentiating between systolic and diastolic dysfunction is essential because their long-term treatments are different33 (Table 434 and Figure 5). The treatments of choice in patients with systolic dysfunction are ACE inhibitors, digoxin, diuretics and beta blockers. In patients with diastolic dysfunction, the cornerstones of treatment depend on the underlying cause. Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers are frequently used when diastolic dysfunction is secondary to ischemia or hypertension.

The history, physical examination, ECG and chest radiographs provide some clues that can be helpful in differentiating systolic and diastolic dysfunction. For example, predominantly systolic dysfunction is suggested by a history of myocardial infarction and younger patient age, a displaced point of maximal impulse and an S3 gallop on the physical examination, the presence of Q waves on the ECG and the finding of cardiomegaly on the chest radiograph. In contrast, diastolic dysfunction is suggested by a history of hypertension and older patient age, a sustained point of maximal impulse and an S4 gallop on the physical examination, left ventricular hypertrophy on the ECG and a normal-sized heart on the chest radiograph.36 However, the findings can overlap considerably, and echocardiography of the heart is usually necessary.