Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(9):2053-2060

Leukocytosis, a common laboratory finding, is most often due to relatively benign conditions (infections or inflammatory processes). Much less common but more serious causes include primary bone marrow disorders. The normal reaction of bone marrow to infection or inflammation leads to an increase in the number of white blood cells, predominantly polymorphonuclear leukocytes and less mature cell forms (the “left shift”). Physical stress (e.g., from seizures, anesthesia or overexertion) and emotional stress can also elevate white blood cell counts. Medications commonly associated with leukocytosis include corticosteroids, lithium and beta agonists. Increased eosinophil or basophil counts, resulting from a variety of infections, allergic reactions and other causes, can lead to leukocytosis in some patients. Primary bone marrow disorders should be suspected in patients who present with extremely elevated white blood cell counts or concurrent abnormalities in red blood cell or platelet counts. Weight loss, bleeding or bruising, liver, spleen or lymph node enlargement, and immunosuppression also increase suspicion for a marrow disorder. The most common bone marrow disorders can be grouped into acute leukemias, chronic leukemias and myeloproliferative disorders. Patients with an acute leukemia are more likely to be ill at presentation, whereas those with a chronic leukemia are often diagnosed incidentally because of abnormal blood cell counts. White blood cell counts above 100,000 per mm3 (100 × 109 per L) represent a medical emergency because of the risk of brain infarction and hemorrhage.

Leukocytosis, defined as a white blood cell count greater than 11,000 per mm3 (11 ×109 per L),1 is frequently found in the course of routine laboratory testing. An elevated white blood cell count typically reflects the normal response of bone marrow to an infectious or inflammatory process. Occasionally, leukocytosis is the sign of a primary bone marrow abnormality in white blood cell production, maturation or death (apoptosis) related to a leukemia or myeloproliferative disorder. Often, the family physician can identify the cause of an elevated white blood cell count based on the findings of the history and physical examination coupled with basic data from the complete blood count.

Production, Maturation and Survival of Leukocytes

Common progenitor cells, referred to as “stem cells,” are located in the bone marrow and give rise to erythroblasts, myeloblasts and megakaryoblasts. Three quarters of the nucleated cells in the bone marrow are committed to the production of leukocytes. These stem cells proliferate and differentiate into granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils and basophils), monocytes and lymphocytes, which together comprise the absolute white blood cell count. Approximately 1.6 billion granulocytes per kg of body weight are produced each day, and 50 to 75 percent of these cells are neutrophils.2 An abnormal elevation in the neutrophil count (neutrophilia) occurs much more commonly than an increase in eosinophils or basophils.

The maturation of white blood cells in the bone marrow and their release into the circulation are influenced by colony-stimulating factors, interleukins, tumor necrosis factor and complement components.3 Approximately 90 percent of white blood cells remain in storage in the bone marrow, 2 to 3 percent are circulating and 7 to 8 percent are located in tissue compartments.

The cells within the bone marrow compartment are classified into two populations: those that are in the process of DNA synthesis and maturation and those that are in a storage phase awaiting release into the circulating pool. The storage of maturing cells allows for rapid response to the demand for increased white blood cells, with a two- to threefold increase in circulating leukocytes possible in just four to five hours.

The circulating pool of neutrophils is divided into two classes. One pool of cells is circulating freely, and the second pool is deposited along the margins of blood vessel walls. When stimulated by infection, inflammation, drugs or metabolic toxins, the deposited cells “demarginate” and enter the freely circulating pool.

Once a leukocyte is released into circulation and tissue, it remains there only a few hours, at which time cell death occurs. The estimated life span of a white blood cell is 11 to 16 days, with bone marrow maturation and storage comprising the majority of the cell's life.

Etiology of Leukocytosis

The investigation of leukocytosis begins with an understanding of its two basic causes: (1) the appropriate response of normal bone marrow to external stimuli and (2) the effect of a primary bone marrow disorder. Physiologic mechanisms of leukocytosis are listed in Table 1.

| Normally responding bone marrow |

| Infection |

| Inflammation: tissue necrosis, infarction, burns, arthritis |

| Stress: overexertion, seizures, anxiety, anesthesia |

| Drugs: corticosteroids, lithium, beta agonists |

| Trauma: splenectomy |

| Hemolytic anemia |

| Leukemoid malignancy |

| Abnormal bone marrow |

| Acute leukemias |

| Chronic leukemias |

| Myeloproliferative disorders |

Leukocytosis with Normal Bone Marrow

In most instances, increased white blood cell counts are the result of normal bone marrow reacting to inflammation or infection. Most of these cells are polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PML). Circulating PML and less mature forms (e.g., band cells and metamyelocytes) move to a site of injury or infection. This is followed by the release of stored leukocytes, commonly referred to as a “left shift.” Inflammation-associated leukocytosis occurs in tissue necrosis, infarction, burns and arthritis.

Leukocytosis may also occur as a result of physical and emotional stress.4,5 This is a transient process that is not related to marrow production or the release of band cells or other immature cells. Causes of stress leukocytosis include overexertion, seizures, anxiety, anesthesia and epinephrine administration. Stress leukocytosis reverses within hours of elimination of the inciting factor.

Other causes of leukocytosis include medications, splenectomy, hemolytic anemia and malignancy. Medications commonly associated with leukocytosis include corticosteroids, lithium and beta agonists.1,6,7 Splenectomy causes a transient leukocytosis that lasts for weeks to months. In hemolytic anemia, non-specific increases in leukocyte production and release occur in association with increased red blood cell production; marrow growth factors are likely contributors. Malignancy is another recognized cause of leukocytosis (and, occasionally, thrombocytosis); the tumor non-specifically stimulates the marrow to produce leukocytosis.

An excessive white blood cell response (i.e., more than 50,000 white blood cells per cm3 [50 × 109 per L]) associated with a cause outside the bone marrow is termed a “leukemoid reaction.” Even this exaggerated white blood cell count is usually caused by relatively benign processes (i.e., infection or inflammation). An underlying malignancy is the most serious but least common cause of a leukemoid reaction.

As mentioned previously, an increase in neutrophils is the most common cause of an elevated white blood cell count, but other sub-populations of cells (eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes and monocytes) can also give rise to increased leukocyte numbers.

EOSINOPHILIA

Eosinophils are white blood cells that participate in immunologic and allergic events. Common causes of eosinophilia are listed in Table 2. The relative frequency of each cause usually relates to the clinical setting. For example, parasitic infections are often responsible for eosinophilia in pediatric patients, and drug reactions commonly cause an increased eosinophil count in hospitalized patients. Dermatologists frequently find eosinophilia in patients with skin rashes, and pulmonologists often see elevated numbers of eosinophils in conjunction with pulmonary infiltrates and bronchoallergic reactions.

| Allergic events |

| Parasitic infections |

| Dermatologic conditions |

| Infections: scarlet fever, chorea, leprosy, genitourinary infections |

| Immunologic disorders: rheumatoid arthritis, periarteritis, lupus erythematosus, eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome |

| Pleural and pulmonary conditions: Löffler's syndrome, pulmonary infiltrates and eosinophilia |

| Malignancies: non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, Hodgkin's disease |

| Myeloproliferative disorders: chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis |

| Adrenal insufficiency: Addison's disease |

| Sarcoidosis |

Other causes of eosinophilia include malignancies, especially those affecting the immune system (Hodgkin's disease and non-Hodgkin's lymphoma),8 and immunologic disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis and periarteritis. Eosinophilia-myalgia syndrome, a recently described disorder associated with dietary supplements of tryptophan, resembles a connective tissue disease with fibrosis of muscle fascial tissue and peripheral eosinophilia.9

BASOPHILIA

Basophilia is an uncommon cause of leukocytosis. Basophils are inflammatory mediators of substances such as histamine. These cells, along with similar tissue-based cells (mast cells), have receptors for IgE and participate in the degranulation of white blood cells that occurs during allergic reactions, including anaphylaxis.10 Causes of basophilia, some of uncertain origin, are listed in Table 3.

| Infections: viral infections (varicella), chronic sinusitis |

| Inflammatory conditions: inflammatory bowel disease, chronic airway inflammation, chronic dermatitis |

| Myeloproliferative disorders: chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis |

| Alteration of marrow and reticuloendothelial compartments: chronic hemolytic anemia, Hodgkin's disease, splenectomy |

| Endocrinologic causes: hypothyroidism, ovulation, estrogens |

LYMPHOCYTOSIS

Lymphocytes normally represent 20 to 40 percent of circulating white blood cells. Hence, the occurrence of lymphocytosis often translates into an increase in the overall white blood cell count. Increased numbers of lymphocytes occur with certain acute and chronic infections (Table 4). Malignancies of the lymphoid system may also cause lymphocytosis.

| Absolute lymphocytosis |

| Acute infections: cytomegalovirus infection, Epstein-Barr virus infection, pertussis, hepatitis, toxoplasmosis |

| Chronic infections: tuberculosis, brucellosis |

| Lymphoid malignancies: chronic lymphocytic leukemia |

| Relative lymphocytosis |

| Normal in children less than 2 years of age |

| Acute phase of several viral illnesses |

| Connective tissue diseases |

| Thyrotoxicosis |

| Addison's disease |

| Splenomegaly with splenic sequestration |

Relative, rather than absolute, leukocytosis occurs in a number of clinical situations, such as infancy, viral infections, connective tissue diseases, thyrotoxicosis and Addison's disease. Splenomegaly causes relative lymphocytosis as a result of splenic sequestration of granulocytes.

Leukocytosis with Primary Bone Marrow Disorders

Clinical factors that increase suspicion of an underlying bone marrow disorder are listed in Table 5. Bone marrow disorders are generally grouped into leukemias and myeloproliferative disorders.

| Leukocytosis: white blood cell count greater than 30,000 per mm3 (30 × 109 per L)* |

| Concurrent anemia or thrombocytopenia |

| Organ enlargement: liver, spleen or lymph nodes |

| Life-threatening infection or immunosuppression |

| Bleeding, bruising or petechiae |

| Lethargy or significant weight loss |

Marrow abnormalities may occur with stem cells (acute leukemia) or more differentiated cells (chronic leukemia). Delineating acute leukemias from chronic leukemias is clinically important because the acute forms are more often associated with rapidly life-threatening complications such as bleeding, brain infarction and infection. Differences in the clinical presentations of acute and chronic leukemias are provided in Table 6.

| Patient group and type of leukemia | Symptoms | Signs | Laboratory findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children: acute lymphocytic leukemia | Infection, bleeding, weakness | Enlarged liver, spleen or lymph nodes | Variable white blood cell count, anemia, thrombocytopenia, blast cells |

| Adults: acute nonlymphocytic leukemia (acute myeloid leukemia) | |||

| Adults: chronic myelogenous leukemia | None, or malaise and abdominal discomfort | Enlarged spleen | Leukocytosis (myeloid precursors), normal or increased platelet count |

| Older adults: chronic lymphocytic leukemia | None, or nonspecific symptoms | Enlarged spleen or lymph nodes | Leukocytosis (lymphocytes) |

ACUTE LEUKEMIAS

Patients with an acute leukemia often present with signs and symptoms of bone marrow failure, such as fatigue and pallor, fever, infection and/or bleeding with purpura and petechiae. In acute leukemias, the marrow is typically overpopulated with blast cells. These cells are indistinguishable from stem cells by light microscopy, but the term “blast” implies an acute leukemic clone. The maturing normal marrow cellular elements are decreased or absent. Peripheral leukemic cell counts may range from leukocytosis to leukopenia, but, as anticipated, anemia and thrombocytopenia are common.

The acute leukemias are broadly divided into two classes based on the cell of origin: acute lymphocytic leukemia and acute non-lymphocytic leukemia. The previous designation of “acute myeloid leukemia” has been replaced by “acute nonlymphocytic leukemia” to appropriately encompass the full variety of possible abnormal cells (undifferentiated, myeloid, monocytic and megakaryocytic).

Acute lymphocytic leukemia most commonly occurs in children less than 18 years of age. Adults usually have acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Occasionally, patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia have a mediastinal mass or central nervous system involvement at the onset of illness.

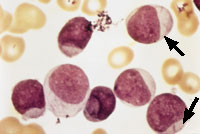

Blast cells are often seen in the peripheral blood smears of patients with acute leukemia. Auer rods, as shown in Figure 1, are a marker of acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Because Auer rods do not appear frequently, precise distinction between acute lymphocytic leukemia and acute nonlymphocytic leukemia usually cannot be accomplished based on the peripheral smear alone; histochemistry, immunotyping and chromosome analysis are usually required.

All patients with acute leukemia require prompt attention and therapy. White blood cell counts in excess of 100,000 per mm3 (100 × 109 per L) constitute a medical emergency because patients with this degree of leukocytosis are predisposed to brain infarction or hemorrhage.

CHRONIC LEUKEMIAS

Patients with a chronic leukemia typically present with much less severe illness than those with an acute leukemia. Chronic leukemia is usually diagnosed incidentally based on high white blood cell counts. The chronic leukemias are divided into two groups according to the cell of origin: chronic lymphocytic leukemia and chronic myelogenous leukemia.

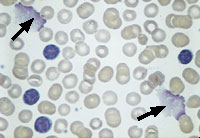

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia results from the proliferation and persistence (lack of apoptosis) of relatively mature-appearing lymphocytes (Figure 2). The spleen and lymph nodes are enlarged because of the excessive accumulation of lymphocytes. Despite the increased number of lymphocytes, this disease is associated with impaired immunity as a result of the scarcity of normal lymphocytes.

Unless complications are present, patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia do not require urgent referral to a hematologist. In the absence of symptoms, such as fever, sweats, weight loss, anemia, moderate thrombocytopenia or organ enlargement, the leukocytosis usually does not require treatment.

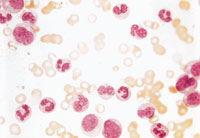

Chronic myelogenous leukemia, which affects myeloid cells (polymorphonuclear cells and less mature cell forms), is frequently diagnosed after the incidental finding of a high white blood cell count. A peripheral blood smear from a patient with this form of leukemia is shown in Figure 3. In some situations, the smear can also show increases in basophils or eosinophils.

Middle-aged adults more commonly develop chronic myelogenous leukemia. Some patients describe fatigue, bleeding or weight loss. Splenomegaly is frequently present, and the markedly enlarged spleen sometimes causes abdominal discomfort, indigestion or early satiety. Lymphadenopathy is uncommon.

Platelet counts are usually normal to increased. In fact, chronic myelogenous leukemia is the only leukemic process that is associated with thrombocytosis. Another laboratory feature that distinguishes this disease from other leukemias and myeloproliferative disorders is the presence of the Philadelphia chromosome, an abnormality of translocation between chromosome 22 and chromosome 9.

Chronic myelogenous leukemia eventually develops an accelerated phase and subsequently transforms into acute leukemia. The accelerated phase is characterized by fever, sweats, weight loss, bone pain, bruising and hepatosplenomegaly. During this time, thrombocytopenia and anemia develop. The median time for transformation of chronic myelogenous leukemia to acute leukemia is two to five years. After the development of acute leukemia, median survival is short.

MYELOPROLIFERATIVE DISORDERS

The myeloproliferative disorders include chronic myelogenous leukemia, polycythemia vera, myelofibrosis and essential thrombocythemia (Table 7). Because all of these entities may present with leukocytosis, differentiation can be difficult and usually requires special laboratory studies and bone marrow examinations.11

| Disease | Red blood cells | White blood cells | Platelets | Marrow |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polycythemia vera | Increased | Normal or increased | Normal or increased | Hypercellular |

| Chronic myelogenous leukemia | Normal or increased | Increased | Normal or increased | Hypercellular |

| Myelofibrosis | Normal or decreased | Variable | Variable | Fibrosis |

| Essential thrombocythemia | Normal or decreased | Slightly increased or normal | Increased | Hypercellular |

Polycythemia vera usually presents with excessive numbers of erythroid cells, but increased white blood cell and platelet counts may also be evident. Symptoms resulting from hypervolemia and hyperviscosity, such as headache, dizziness, visual disturbances and paresthesias, are sometimes present. Less frequently, patients with polycythemia vera develop myocardial infarction, stroke, venous thrombosis and congestive heart failure. Overall survival is long (10 to 20 years).

Myelofibrosis is a bone marrow disorder in which fibroblasts replace normal elements of the marrow. Patients with myelofibrosis are usually 50 years or older and have a median survival of less than 10 years. As bone marrow fibrosis develops, patients can present with leukocytosis, although decreased white blood cell, red blood cell and platelet counts are more common. Patients are asymptomatic early in the course of the disease and are usually diagnosed incidentally based on changes in blood cell counts. Symptomatic patients have fatigue, shortness of breath, weight loss, bleeding or abdominal discomfort related to splenomegaly. Acute leukemia can develop over time and, when it occurs, progresses rapidly.

Leukocytosis is also found in patients with essential thrombocythemia (primary thrombocythemia). Although elevated platelet counts occur in all myeloproliferative disorders, essential thrombocythemia is distinguished by the singular prominence of platelets. Markers of other disorders, such as the Philadelphia chromosome and bone marrow fibrosis, are absent. It is important to exclude secondary thrombocytosis caused by nonmarrow disorders (e.g., iron deficiency or bleeding). Most patients with essential thrombocythemia are asymptomatic and require little, if any, therapy, although some patients develop thrombosis or hemorrhage secondary to increased numbers of dysfunctional platelets.

Final Comment

Excessive numbers of white blood cells are most often due to the response of normal bone marrow to infection or inflammation. In some instances, leukocytosis is a sign of more serious primary bone marrow disease (leukemias or myeloproliferative disorders). Attention to clinical factors associated with marrow disorders, such as extremely elevated white blood cell counts, abnormalities in red blood cell or platelet counts, weight loss, bleeding and organ enlargement, can help the family physician decide which patients require further investigation and consultation.