Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(8):1585-1590

A more recent article on prevention and repair of obstetric lacerations is available.

Family physicians who deliver babies must frequently repair perineal lacerations after episiotomy or spontaneous obstetric tears. Effective repair requires a knowledge of perineal anatomy and surgical technique. Perineal lacerations are classified according to their depth. Sequelae of obstetric lacerations include chronic perineal pain, dyspareunia, urinary incontinence, and fecal incontinence. With lacerations involving the anal sphincter complex, particular attention must be given to anatomy and surgical technique because of the high incidence of poor functional outcomes after repair. An overlapping technique to repair the external anal sphincter, rather than the traditional end-to-end technique, is being investigated to determine if it might decrease the incidence of anal incontinence. Minimizing the use of episiotomy and forceps deliveries can decrease the occurrence of severe perineal lacerations.

Perineal repair after episiotomy or spontaneous obstetric laceration is one of the most common surgical procedures. Potential sequelae of obstetric perineal lacerations include chronic perineal pain,1 dyspareunia,2 and urinary and fecal incontinence.3–5 Few studies of laceration repair techniques exist to support the development of an evidence-based approach to perineal repair. This article discusses a repair method that emphasizes anatomic detail, with the expectation that an anatomically correct perineal repair may result in a better long-term functional outcome.

Perineal Anatomy

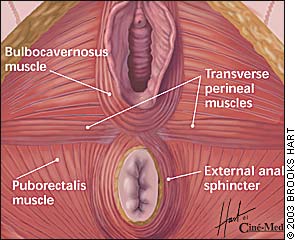

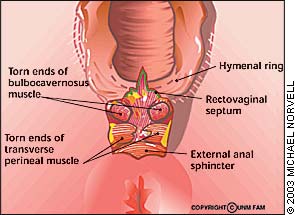

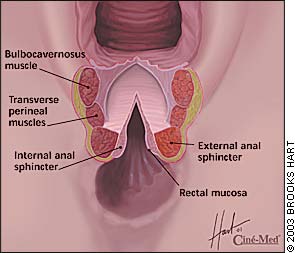

The perineal body, located between the vagina and the rectum, is formed predominantly by the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles (Figure 1). The puborectalis muscle and the external anal sphincter contribute additional muscle fibers.

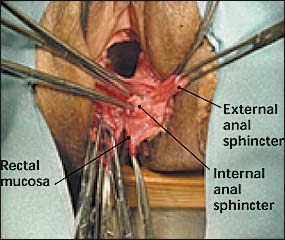

The anal sphincter complex lies inferior to the perineal body (Figure 2). The external anal sphincter is composed of skeletal muscle. The internal anal sphincter, which overlaps and lies superior to the external anal sphincter, is composed of smooth muscle and is continuous with the smooth muscle of the colon. The anal sphincter complex extends for a distance of 3 to 4 cm.6

Surgical Principles

Obstetric perineal lacerations are classified as first to fourth degree, depending on their depth. A rectal examination is helpful in determining the extent of injury and ensuring that a third- or fourth-degree laceration is not overlooked.

Repair of the perineum requires good lighting and visualization, proper surgical instruments and suture material, and adequate analgesia (Table 1). Compared with surgical repair using catgut or chromic suture, repair using 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) suture results in decreased wound dehiscence and less postpartum perineal pain.9–12 [ Reference9—Evidence level A, randomized controlled trial (RCT); Reference10—Evidence level B, uncontrolled trial; Reference11—Evidence level A, meta-analysis; Reference12—Evidence level B—systematic review of RCTs] Use of rapidly absorbed polyglactin 910 (Vicryl Rapide) suture decreases the need for postpartum suture removal after repair of second-degree lacerations.13

| Sterile drapes and gloves |

| Irrigation solution |

| Needle holder |

| Metzenbaum scissors |

| Suture scissors |

| Forceps with teeth |

| Allis clamps |

| Gelpi or Deaver retractor (for use in visualizing third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, or deep vaginal lacerations) |

| 10-mL syringe with 22-gauge needle |

| 1% lidocaine (Xylocaine) |

| 3-0 polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) suture on CT-1 needle (for vaginal mucosa sutures) |

| 3-0 polyglactin 910 suture on CT-1 needle (for perineal muscle sutures) |

| 4-0 polyglactin 910 suture on SH needle (for skin sutures) |

| 2-0 polydioxanone sulfate (PDS) suture on CT-1 needle (for external anal sphincter sutures) |

Local anesthesia can be used for repair of most perineal lacerations. However, general or regional anesthesia may be necessary to achieve adequate muscle relaxation and visualization for surgical repair of severe or complex lacerations.

Severe perineal lacerations involving the anal sphincter complex pose a surgical challenge. Recent studies3,14 have demonstrated a 20 to 50 percent incidence of anal incontinence or rectal urgency after repair of third-degree obstetric perineal lacerations. These injuries do not require immediate repair; hence, an inexperienced physician can delay the procedure for a few hours until appropriate support staff are available.

With severe perineal lacerations involving the anal sphincter complex, we irrigate copiously to improve visualization and reduce the incidence of wound infection. Because these lacerations are contaminated by stool, a single dose of a second- or third-generation cephalosporin may be given intravenously before the procedure is started.

Repair of Second-Degree Perineal Lacerations

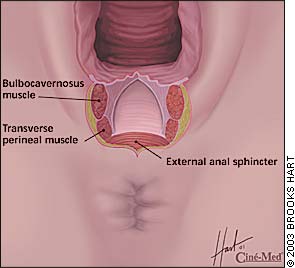

Repair of a second-degree laceration (Figure 3) requires approximation of the vaginal tissues, muscles of the perineal body, and perineal skin. The steps in the procedure are as follows:

The apex of the vaginal laceration is identified. For lacerations extending deep into the vagina, a Gelpi or Deaver retractor facilitates visualization.

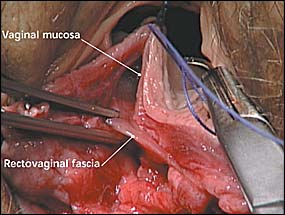

An anchoring suture is placed 1 cm above the apex of the laceration, and the vaginal mucosa and underlying rectovaginal fascia are closed using a running unlocked 3-0 polyglactin 910 suture. If the apex is too far into the vagina to be seen, the anchoring suture is placed at the most distally visible area of laceration, and traction is applied on the suture to bring the apex into view. The running suture can be locked for hemostasis, if needed.

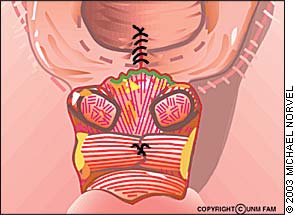

The sutures must include the rectovaginal fascia (Figure 4), which provides support to the posterior vagina. The running suture is carried to the hymenal ring and tied proximal to the ring, completing closure of the vaginal mucosa and rectovaginal fascia.

A single interrupted 3-0 polyglactin 910 suture is then placed through the bulbocavernosus muscle (Figure 7). The torn ends of the bulbocavernosus muscle are frequently retracted posteriorly and superiorly. Use of a large needle facilitates proper suture placement.

If the laceration has separated the rectovaginal fascia from the perineal body, the fascia is reattached to the perineal body with two vertical interrupted 3-0 polyglactin 910 sutures (Figure 8)

When the perineal muscles are repaired anatomically as described above, the overlying skin is usually well approximated, and skin sutures generally are not required. Skin sutures have been shown to increase the incidence of perineal pain at three months after delivery.15 [Evidence level B, uncontrolled trial] If the skin requires suturing, running subcuticular sutures have been shown to be superior to interrupted transcutaneous sutures.16 The 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures should start at the posterior apex of the skin laceration and should be placed approximately 3 mm from the edge of the skin.

An alternative approach to repair of the perineal body muscles is a running suture that is continued from the vaginal mucosa repair and brought underneath the hymenal ring. However, we prefer the interrupted approach because it facilitates a more anatomic repair, allowing reapproximation of the bulbocavernosus muscle and reattachment of the vaginal septum with minimal use of sutures.

Repair of Fourth-Degree Perineal Lacerations

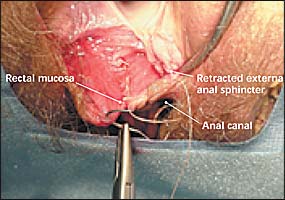

Repair of a fourth-degree laceration requires approximation of the rectal mucosa, internal anal sphincter, and external anal sphincter (Figure 9)

A Gelpi retractor is used to separate the vaginal sidewalls to permit visualization of the rectal mucosa and anal sphincters. The apex of the rectal mucosa is identified, and the mucosa is approximated using closely spaced interrupted or running 4-0 polyglactin 910 sutures (Figure 10). Traditional recommendations emphasize that sutures should not penetrate the complete thickness of the mucosa into the anal canal, to avoid promoting fistula formation. The sutures are continued to the anal verge (i.e., onto the perineal skin).

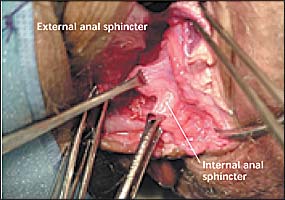

The internal anal sphincter is identified as a glistening, white, fibrous structure between the rectal mucosa and the external anal sphincter (Figure 11). The sphincter may be retracted laterally, and placement of Allis clamps on the muscle ends facilitates repair. The internal anal sphincter is closed with continuous 2-0 polyglactin 910 sutures.

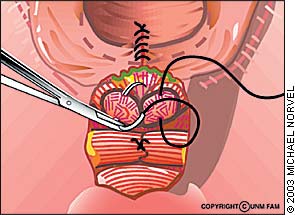

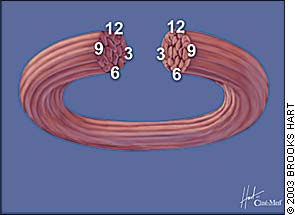

The external anal sphincter appears as a band of skeletal muscle with a fibrous capsule. Traditionally, an end-to-end technique is used to bring the ends of the sphincter together at each quadrant (12, 3, 6, and 9 o'clock) using interrupted sutures placed through the capsule and muscle (Figure 12). Allis clamps are placed on each end of the external anal sphincter. We use 2-0 polydioxanone sulfate (PDS), a delayed absorbable monofilament suture, to allow the sphincter ends adequate time to scar together. Recent evidence suggests that end-to-end repairs have poorer anatomic and functional outcomes than was previously believed.3,4 [ Reference3 —Evidence level B, descriptive study; Reference4 —Evidence level B, prospective cohort study]

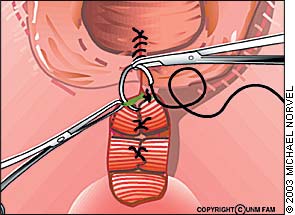

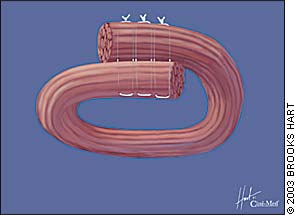

An alternative technique is overlapping repair of the external anal sphincter. Colorectal surgeons prefer to use this method when they repair the sphincter remote from delivery.14,17 The overlapping technique brings together the ends of the sphincter with mattress sutures (Figure 13) and results in a larger surface area of tissue contact between the two torn ends. Dissection of the external anal sphincter from the surrounding tissue with Metzenbaum scissors may be required to achieve adequate length for the overlapping of the muscles. The suture is passed from top to bottom through the superior and inferior flaps, then from bottom to top through the inferior and superior flaps. The proximal end of the superior flap overlies the distal portion of the inferior flap. Two more sutures are placed in the same manner. After all three sutures are placed, they are each tied snugly, but without strangulation. When tied, the knots are on the top of the overlapped sphincter ends. Care must be taken to incorporate the muscle capsule in the closure.

Postpartum Care

The literature contains little information on patient care after the repair of perineal lacerations. We recommend the use of sitz baths and an analgesic such as ibuprofen. If a woman has excessive pain in the days after a repair, she should be examined immediately because pain is a frequent sign of infection in the perineal area. After repair of a third- or fourth-degree laceration, we include several weeks of therapy with a stool softener, such as docusate sodium (Colace), to minimize the potential for repair breakdown from straining during defecation.

The perineal muscles, vaginal mucosa, and skin are repaired using the same techniques described for the repair of second-degree lacerations.

Prevention

The incidence of severe perineal trauma can be decreased by minimizing the use of episiotomy and operative vaginal delivery. A Cochrane review demonstrated that liberal use of episiotomy does not reduce the incidence of anal sphincter lacerations and is associated with increased perineal trauma.18 [Evidence level A, systematic review of RCTs] A meta-analysis of eight randomized trials of vacuum extraction versus forceps delivery demonstrated that one sphincter tear would be prevented for every 18 women delivered with vacuum rather than forceps.19 [Evidence level B, systematic review of lower quality RCTs]