Am Fam Physician. 2007;75(6):875-882

A more recent article on postpartum hemorrhage is available.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Postpartum hemorrhage, the loss of more than 500 mL of blood after delivery, occurs in up to 18 percent of births and is the most common maternal morbidity in developed countries. Although risk factors and preventive strategies are clearly documented, not all cases are expected or avoidable. Uterine atony is responsible for most cases and can be managed with uterine massage in conjunction with oxytocin, prostaglandins, and ergot alkaloids. Retained placenta is a less common cause and requires examination of the placenta, exploration of the uterine cavity, and manual removal of retained tissue. Rarely, an invasive placenta causes postpartum hemorrhage and may require surgical management. Traumatic causes include lacerations, uterine rupture, and uterine inversion. Coagulopathies require clotting factor replacement for the identified deficiency. Early recognition, systematic evaluation and treatment, and prompt fluid resuscitation minimize the potentially serious outcomes associated with postpartum hemorrhage.

Postpartum hemorrhage, defined as the loss of more than 500 mL of blood after delivery, occurs in up to 18 percent of births.1,2 Blood loss exceeding 1,000 mL is considered physiologically significant and can result in hemodynamic instability.3 Even with appropriate management, approximately 3 percent of vaginal deliveries will result in severe post-partum hemorrhage.4 It is the most common maternal morbidity in developed countries and a major cause of death worldwide.1,3

Complications from postpartum hemorrhage include orthostatic hypotension, anemia, and fatigue, which may make maternal care of the newborn more difficult. Post-partum anemia increases the risk of post-partum depression.5 Blood transfusion may be necessary and carries associated risks.6 In the most severe cases, hemorrhagic shock may lead to anterior pituitary ischemia with delay or failure of lactation (i.e., postpartum pituitary necrosis).7,8 Occult myocardial ischemia, dilutional coagulopathy, and death also may occur.9 Delayed postpartum hemorrhage, bleeding after 24 hours as a result of sloughing of the placental eschar or retained placental fragments, also can occur.10

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Active management of the third stage of labor decreases postpartum blood loss and the risk of postpartum hemorrhage (number needed to treat=12). | A | 2,17 |

| Active management of the third stage of labor does not increase the risk of retained placenta. | A | 2,17,18 |

| Oxytocin (Pitocin) is the first choice for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage because it is as effective or more effective than ergot alkaloids or prostaglandins and has fewer side effects. | A | 2,25,26 |

| Misoprostol (Cytotec) may be used when other oxytocic agents are not available for prevention of postpartum hemorrhage (number needed to treat=18). | A | 27 |

| Misoprostol may be used for treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, but this agent is associated with more side effects than conventional uterotonic drugs. | A | 37 |

| Routine episiotomy increases anal sphincter tears and blood loss. | A | 11,40 |

Prevention

Risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage include a prolonged third stage of labor, multiple delivery, episiotomy, fetal macrosomia, and history of postpartum hemorrhage.3,4,11,12 However, postpartum hemorrhage also occurs in women with no risk factors, so physicians must be prepared to manage this condition at every delivery.13 Strategies for minimizing the effects of postpartum hemorrhage include identifying and correcting anemia before delivery, being aware of the mother's beliefs about blood transfusions, and eliminating routine episiotomy.14–16 Reexamination of the patient's vital signs and vaginal flow before leaving the delivery area may help detect slow, steady bleeding.

The best preventive strategy is active management of the third stage of labor (number needed to treat [NNT] to prevent one case of postpartum hemorrhage = 12).17,18 Hospital guidelines encouraging this practice have resulted in significant reductions in the incidence of massive hemorrhage.19 Active management, which involves administering a uterotonic drug with or soon after the delivery of the anterior shoulder, controlled cord traction, and, usually, early cord clamping and cutting, decreases the risk of postpartum hemorrhage and shortens the third stage of labor with no significant increase in the risk of retained placenta.17,18 Compared with expectant management, in which the placenta is allowed to separate spontaneously aided only by gravity or nipple stimulation, active management decreases the incidence of postpartum hemorrhage by 68 percent.17

Early cord clamping is no longer included in the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) definition of active management of the third stage of labor, and uterine massage after delivery of the placenta has been added.20 Delaying cord clamping for about 60 seconds has the benefit of increasing iron stores and decreasing anemia, which is especially important in preterm infants and in low-resource settings.16,21–23 The delay has not been shown to increase neonatal morbidity or maternal blood loss.16,21,23

Prophylactic administration of oxytocin (Pitocin) reduces rates of postpartum hemorrhage by 40 percent24; this reduction also occurs if oxytocin is given after placental delivery.2,18 Oxytocin is the drug of choice for preventing postpartum hemorrhage because it is at least as effective as ergot alkaloids or prostaglandins and has fewer side effects.2,25,26 Misoprostol (Cytotec) has a role in the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage (NNT = 18)16; this agent has more side effects but is inexpensive, heat- and light-stable, and requires no syringes.27

Diagnosis and Management

| Four Ts | Cause | Approximate incidence (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Tone | Atonic uterus | 70 |

| Trauma | Lacerations, hematomas, inversion, rupture | 20 |

| Tissue | Retained tissue, invasive placenta | 10 |

| Thrombin | Coagulopathies | 1 |

TONE

Uterine atony is the most common cause of postpartum hemorrhage.28 Because hemostasis associated with placental separation depends on myometrial contraction, atony is treated initially by bimanual uterine compression and massage, followed by drugs that promote uterine contraction.

Uterine Massage

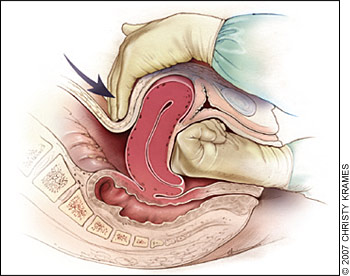

Brisk blood flow after delivery of the placenta should alert the physician to perform a bimanual examination of the uterus. If the uterus is soft, massage is performed by placing one hand in the vagina and pushing against the body of the uterus while the other hand compresses the fundus from above through the abdominal wall (Figure 2).29 The posterior aspect of the uterus is massaged with the abdominal hand and the anterior aspect with the vaginal hand.

Uterotonic Agents

Uterotonic agents include oxytocin, ergot alkaloids, and prostaglandins. Oxytocin stimulates the upper segment of the myometrium to contract rhythmically, which constricts spiral arteries and decreases blood flow through the uterus.30 Oxytocin is an effective first-line treatment for postpartum hemorrhage31; 10 international units (IU) should be injected intramuscularly, or 20 IU in 1 L of saline may be infused at a rate of 250 mL per hour. As much as 500 mL can be infused over 10 minutes without complications.10

Methylergonovine (Methergine) and ergometrine (not available in the United States) are ergot alkaloids that cause generalized smooth muscle contraction in which the upper and lower segments of the uterus contract tetanically.32 A typical dose of methylergonovine, 0.2 mg administered intramuscularly, may be repeated as required at intervals of two to four hours. Because ergot alkaloid agents raise blood pressure, they are contraindicated in women with preclampsia or hypertension.33 Other adverse effects include nausea and vomiting.33

Prostaglandins enhance uterine contractility and cause vasoconstriction.34 The prostaglandin most commonly used is 15-methyl prostaglandin F2a, or carboprost (Hemabate). Carboprost can be administered intramyometrially or intramuscularly in a dose of 0.25 mg; this dose can be repeated every 15 minutes for a total dose of 2 mg. Carboprost has been proven to control hemorrhage in up to 87 percent of patients.35 In cases where it is not effective, chorioamnionitis or other risk factors for hemorrhage often are present.35 Hypersensitivity is the only absolute contraindication, but carboprost should be used with caution in patients with asthma or hypertension. Side effects include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hypertension, headache, flushing, and pyrexia.34

Misoprostol is another prostaglandin that increases uterine tone and decreases postpartum bleeding.36 Misoprostol is effective in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, but side effects may limit its use.28,37 It can be administered sublingually, orally, vaginally, and rectally. Doses range from 200 to 1,000 mcg; the dose recommended by FIGO is 1,000 mcg administered rectally.28,37,38 Higher peak levels and larger doses are associated with more side effects, including shivering, pyrexia, and diarrhea.28,39 Although misoprostol is widely used in the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage, it is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for this indication.

TRAUMA

Lacerations and hematomas resulting from birth trauma can cause significant blood loss that can be lessened by hemostasis and timely repair. Sutures should be placed if direct pressure does not stop the bleeding. Episiotomy increases blood loss and the risk of anal sphincter tears,11,12,40 and this procedure should be avoided unless urgent delivery is necessary and the perineum is thought to be a limiting factor.14

Hematomas can present as pain or as a change in vital signs disproportionate to the amount of blood loss. Small hematomas can be managed with close observation.41 Patients with persistent signs of volume loss despite fluid replacement, as well as those with large or enlarging hematomas, require incision and evacuation of the clot.41 The involved area should be irrigated and the bleeding vessels ligated. In patients with diffuse oozing, a layered closure will help to secure hemostasis and eliminate dead space.

Uterine Inversion

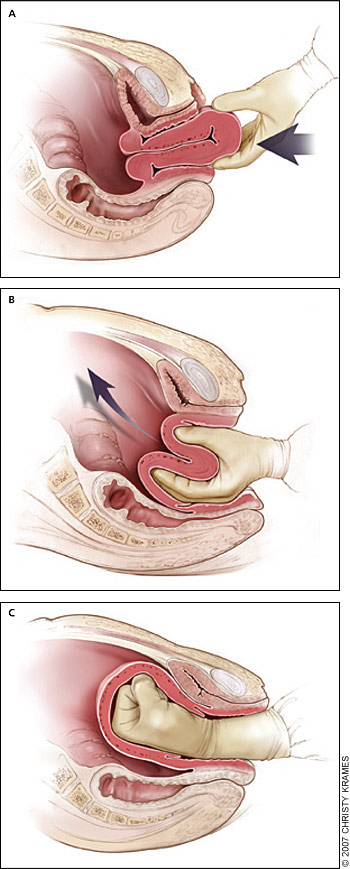

Uterine inversion is rare, occurring in 0.05 percent of deliveries.10 Active management of the third stage of labor may reduce the incidence of uterine inversion.42 Fundal implantation of the placenta may lead to inversion; the roles of fundal pressure and undue cord traction are uncertain.10 The inverted uterus usually appears as a bluish-gray mass protruding from the vagina. Vasovagal effects producing vital sign changes disproportionate to the amount of bleeding may be an additional clue. The placenta often is still attached, and it should be left in place until after reduction.42 Every attempt should be made to replace the uterus quickly. The Johnson method of reduction begins with grasping the protruding fundus Figure 3A29 ) with the palm of the hand and fingers directed toward the posterior fornix (Figure 3B29). The uterus is returned to position by lifting it up through the pelvis and into the abdomen (Figure 3C29).43 Once the uterus is reverted, uterotonic agents should be given to promote uterine tone and to prevent recurrence. If initial attempts to replace the uterus fail or a cervical contraction ring develops, administration of magnesium sulfate, terbutaline (Brethine), nitroglycerin, or general anesthesia may allow sufficient uterine relaxation for manipulation. If these methods fail, the uterus will need to be replaced surgically.42

Uterine Rupture

Although rare in an unscarred uterus, clinically significant uterine rupture occurs in 0.6 to 0.7 percent of vaginal births after cesarean delivery in women with a low transverse or unknown uterine scar.44–46 The risk increases significantly with previous classical incisions or uterine surgeries, and to a lesser extent with shorter intervals between pregnancies or a history of multiple cesarean deliveries, particularly in women with no previous vaginal deliveries.44–48 Compared with spontaneous labor, induction or augmentation increases the rate of uterine rupture, more so if prostaglandins and oxytocin are used sequentially. However, the incidence of rupture is still low (i.e., 1 to 2.4 percent).46,48 Misoprostol should not be used for cervical ripening or induction when attempting vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery.48

Before delivery, the primary sign of uterine rupture is fetal bradycardia.45 Tachycardia or late decelerations can also herald a uterine rupture, as can vaginal bleeding, abdominal tenderness, maternal tachycardia, circulatory collapse, or increasing abdominal girth.47 Symptomatic uterine rupture requires surgical repair of the defect or hysterectomy. When detected in the postpartum period, a small asymptomatic lower uterine segment defect or bloodless dehiscence can be followed expectantly.47

TISSUE

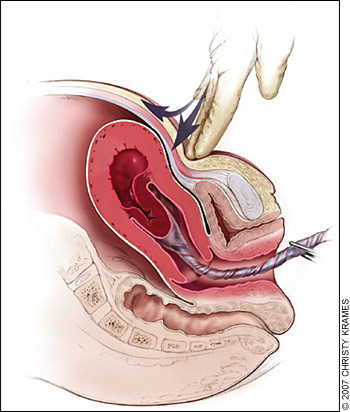

Classic signs of placental separation include a small gush of blood with lengthening of the umbilical cord and a slight rise of the uterus in the pelvis. Placental delivery can be achieved by use of the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, which involves applying firm traction on the umbilical cord with one hand while the other applies suprapubic counterpressure (Figure 429).49 The mean time from delivery until placental expulsion is eight to nine minutes.4 Longer intervals are associated with an increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, with rates doubling after 10 minutes.4 Retained placenta (i.e., failure of the placenta to deliver within 30 minutes after birth) occurs in less than 3 percent of vaginal deliveries.50 One management option is to inject the umbilical vein with 20 mL of a solution of 0.9 percent saline and 20 units of oxytocin. This significantly reduces the need for manual removal of the placenta compared with injecting saline alone.51 Alternatively, physicians may proceed directly to manual removal of the placenta, using appropriate analgesia. If the tissue plane between the uterine wall and placenta cannot be developed through blunt dissection with the edge of the gloved hand, invasive placenta should be considered.

Invasive placenta can be life threatening.50 The incidence has increased from 0.003 percent to 0.04 percent of deliveries since 1950s; this increase is likely a result of the increase in cesarean section rates.49 Classification is based on the depth of invasion and can be easily remembered through alliteration: placenta accreta adheres to the myometrium, placenta increta invades the myometrium, and placenta percreta penetrates the myometrium to or beyond the serosa.10 Risk factors include advanced maternal age, high parity, previous invasive placenta or cesarean delivery, and placenta previa (especially in combination with previous cesarean delivery, increasing to 67 percent with four or more).49 The most common treatment for invasive placenta is hysterectomy.49 However, conservative management (i.e., leaving the placenta in place or giving weekly oral methotrexate52 until ⊠ human chorionic gonadotropin levels are 0) is sometimes successful.53 Women treated for a retained placenta must be observed for late sequelae, including infection and late postpartum bleeding.52,53

THROMBIN

Coagulation disorders, a rare cause of post-partum hemorrhage, are unlikely to respond to the measures described above.10 Most coagulopathies are identified before delivery, allowing for advance planning to prevent postpartum hemorrhage. These disorders include idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, von Willebrand's disease, and hemophilia. Patients also can develop HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and low platelet levels) syndrome or disseminated intravascular coagulation. Risk factors for disseminated intravascular coagulation include severe pre-eclampsia, amniotic fluid embolism, sepsis, placental abruption, and prolonged retention of fetal demise.54,55 Abruption is associated with cocaine use and hypertensive disorders.54 Excessive bleeding can deplete coagulation factors and lead to consumptive coagulation, which promotes further bleeding. Coagulation defects should be suspected in patients who have not responded to the usual measures to treat post-partum hemorrhage, and in those who are not forming blood clots or are oozing from puncture sites.

Evaluation should include a platelet count and measurement of prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, fibrinogen level, and fibrin split products (i.e., d-dimer). Management consists of treating the underlying disease process, supporting intravascular volume, serially evaluating coagulation status, and replacing appropriate blood components. Administration of recombinant factor VIIa or clot-promoting medications (e.g., tranexamic acid [Cyklokapron]) may be considered.33,54,56

Clinical Approach

Significant blood loss from any cause requires standard maternal resuscitation measures (Figure 1). Blood loss of more than 1,000 mL requires quick action and an interdisciplinary team approach.54 Hysterectomy is the definitive treatment in women with severe, intractable hemorrhage. In patients who desire future fertility, uterus-conserving treatments include uterine packing or tamponade procedures, B-lynch uterine compression sutures, artery ligation, and uterine artery embolization.54,57