A more recent article on mastitis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2008;78(6):727-731

Patient information: See related handout on mastitis, written by the author of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Mastitis occurs in approximately 10 percent of U.S. mothers who are breastfeeding, and it can lead to the cessation of breastfeeding. The risk of mastitis can be reduced by frequent, complete emptying of the breast and by optimizing breastfeeding technique. Sore nipples can precipitate mastitis. The differential diagnosis of sore nipples includes mechanical irritation from a poor latch or infant mouth anomalies, such as cleft palate or bacterial or yeast infection. The diagnosis of mastitis is usually clinical, with patients presenting with focal tenderness in one breast accompanied by fever and malaise. Treatment includes changing breastfeeding technique, often with the assistance of a lactation consultant. When antibiotics are needed, those effective against Staphylococcus aureus (e.g., dicloxacillin, cephalexin) are preferred. As methicillin-resistant S. aureus becomes more common, it is likely to be a more common cause of mastitis, and antibiotics that are effective against this organism may become preferred. Continued breastfeeding should be encouraged in the presence of mastitis and generally does not pose a risk to the infant. Breast abscess is the most common complication of mastitis. It can be prevented by early treatment of mastitis and continued breastfeeding. Once an abscess occurs, surgical drainage or needle aspiration is needed. Breastfeeding can usually continue in the presence of a treated abscess.

Mastitis is defined as inflammation of the breast. Although it can occur spontaneously or during lactation, this discussion is limited to mastitis in breastfeeding women, with mastitis defined clinically as localized, painful inflammation of the breast occurring in conjunction with flu-like symptoms (e.g., fever, malaise).

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Optimizing lactation support is essential in women with mastitis. | C | 3, 17 |

| Milk culture is rarely needed in the diagnosis of mastitis, but it should be considered in refractory and hospital-acquired cases. | C | 3, 7, 16 |

| Antibiotics effective against Staphylococcus aureus are preferred in the treatment of mastitis. | C | 16, 17 |

| Breastfeeding in the presence of mastitis generally does not pose a risk to the infant and should be continued to maintain milk supply. | C | 3, 20 |

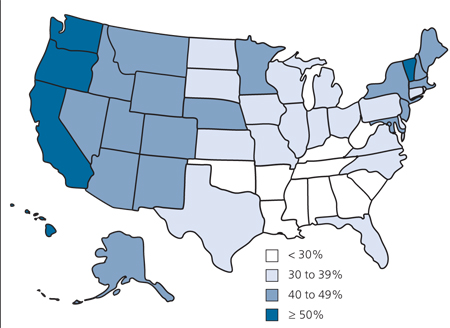

Mastitis is especially problematic because it may lead to the discontinuation of breast-feeding, which provides optimal infant nutrition. The Healthy People 2010 goals for breastfeeding are that 75 percent of mothers initiate breastfeeding, with 50 percent and 25 percent continuing to six and 12 months, respectively.1 As of 2005, most states were not meeting these goals (Figure 1).2 To extend breastfeeding duration, family physicians must become more adept at helping mothers overcome breastfeeding difficulties such as mastitis.

The incidence of mastitis varies widely across populations, likely because of variations in breastfeeding methods and support. Studies have reported the incidence to be as high as 33 percent in lactating women.3 One study of 946 lactating women, followed prospectively, found an incidence of 9.5 percent.4 Although mastitis can occur anytime during lactation, it is most common during the second and third weeks postpartum, with 75 to 95 percent of cases occurring before the infant is three months of age.3 It is equally common in the right and left breast.5 Risk factors for mastitis are listed in Table 1.3,4,6–8

| Cleft lip or palate |

| Cracked nipples |

| Infant attachment difficulties |

| Local milk stasis |

| Missed feeding |

| Nipple piercing* |

| Plastic-backed breast pads |

| Poor maternal nutrition |

| Previous mastitis |

| Primiparity† |

| Restriction from a tight bra |

| Short frenulum in infant |

| Sore nipples |

| Use of a manual breast pump |

| Yeast infection |

Prevention of Mastitis

Few trials have been published on methods to prevent mastitis. Most interventions are based on clinical experience and anecdotal reports. Because mastitis is thought to result partly from inadequate milk removal from the breast, optimizing breastfeeding technique is likely to be beneficial. However, one trial showed that a single 30-minute counseling session on breastfeeding technique does not have a statistically significant effect on the incidence of mastitis.9 Therefore, ongoing support may be necessary to achieve better results. Lactation consultants can be invaluable in this effort. In addition, bedside hand disinfection by breastfeeding mothers in the postpartum unit has been shown to reduce the incidence of mastitis.10

Risk Factors

Sore nipples may be an early indicator of a condition that may predispose patients to mastitis. In the early weeks of breastfeeding, sore nipples are most often caused by a poor latch by the feeding infant. The latch can best be assessed by someone experienced in lactation who observes a feeding. Wearing plastic-backed breast pads can lead to irritation of the nipple from trapped moisture.11 For sore nipples that are overly dry, the application of expressed breast milk or purified lanolin can be beneficial.11

Nipple fissures can cause pain and can serve as a portal of entry for bacteria that result in mastitis. One study randomized mothers with cracked nipples who tested positive for Staphylococcus aureus to breastfeeding education alone, application of topical mupirocin (Bactroban) 2% ointment or fusidic acid ointment (not available in the United States), or oral therapy with cloxacillin (no longer available in the United States) or erythromycin.12 The mothers in the oral antibiotic group had significantly better resolution of cracked nipples.

Blocked milk ducts can also lead to mastitis. This condition presents as localized tenderness in the breast from inadequate milk removal from one duct. A firm, red, tender area is present on the affected breast, and a painful, white, 1-mm bleb may be present on the nipple. This bleb is thought to be an overgrowth of epithelium or an accumulation of particulate or fatty material. Removal of the bleb with a sterile needle or by rubbing with a cloth can be beneficial.3 Other treatments include frequent breastfeeding and the use of warm compresses or showers. Massaging the affected area toward the nipple is often helpful. Constrictive clothing should be avoided.

Yeast infection can increase the risk of mastitis by causing nipple fissures or milk stasis. Yeast infection should be suspected when pain—often described as shooting from the nipple through the breast to the chest wall—is out of proportion to clinical findings. This condition is often associated with other yeast infections, such as oral thrush or diaper dermatitis. Culture of the milk or the infant's mouth is rarely useful. Treatment of both the mother and infant is essential. Topical agents that are often effective include nystatin (Mycostatin) for the infant or mother, or miconazole (Micatin) or ketoconazole (Nizoral, brand no longer available in the United States) for the mother.11 Application of 1% gentian violet in water is an inexpensive and often effective (although messy) alternative. Before a feeding, the solution is applied with a cotton swab to the part of the infant's mouth that comes into contact with the nipple. After the feeding, any areas of the nipple that are not purple are painted with the solution. This procedure is repeated for three to four days.13 Although it is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of mastitis, fluconazole (Diflucan) is often prescribed for the mother and infant with severe cases of mastitis. The dosage for the mother is 400 mg on the first day, followed by 200 mg daily for a minimum of 10 days. Single-dose treatment, such as that used for vaginal candidiasis, is ineffective.11 The infant is not adequately treated by the fluconazole that passes into the breast milk and should be treated with 6 to 12 mg per kg on the first day, followed by 3 to 6 mg per kg per day for at least 10 days.14

Infant mouth abnormalities (e.g., cleft lip or palate) may lead to nipple trauma and increase the risk of mastitis. Infants with a short frenulum (Figure 2) may be unable to remove milk effectively from the breast, leading to nipple trauma. Frenotomy can reduce nipple trauma and is usually a simple, bloodless procedure that can be performed without anesthesia.15 The incision is made through the translucent band of tissue beneath the tongue, avoiding any blood vessels or tissue that can contain nerves or muscle.11

Diagnosis

Culture is rarely used to confirm bacterial infection of the milk because positive cultures can result from normal bacterial colonization, and negative cultures do not rule out mastitis.3,7,16 Culture has been recommended when the infection is severe, unusual, or hospital acquired, or if it fails to respond to two days' treatment with appropriate antibiotics.3 Culture can also be considered in localities with a high prevalence of bacterial resistance. To culture the milk, the mother should cleanse her nipples, hand express a small amount of milk, and discard it. She should then express a milk sample into a sterile container, taking care to avoid touching the nipple to the container.17

Treatment

Treatment of mastitis begins with improving breastfeeding technique. If the mother stops draining the breast during an episode of mastitis, she will have increased milk stasis and is more likely to develop an abscess. Consultation with an experienced lactation consultant is often invaluable. Mothers should drink plenty of fluids and get adequate rest.3,17 Therapeutic ultrasound has not been proven helpful. Homeopathic remedies have not been well studied for safety or effectiveness.18

Because the mother and infant are usually colonized with the same organisms at the time mastitis develops, breastfeeding can continue during an episode of mastitis without worry of the bacterial infection being transmitted to the infant.3 In addition, milk from a breast with mastitis has been shown to contain increased levels of some anti-inflammatory components that may be protective for the infant.19 Continuation of breastfeeding does not pose a risk to the infant; in fact, it allows for a greater chance of breastfeeding after resolution of the mastitis and allows for the most efficient removal of the breast milk from the affected area. However, some infants may dislike the taste of milk from the infected breast, possibly because of the increased sodium content.20 In these cases, the milk can be pumped and discarded.

Vertical transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) from mother to infant is more likely in the presence of mastitis.3,21 This is especially important in developing countries where mothers who are HIV-positive may be breastfeeding.3 The World Health Organization recommends that women with HIV infection who are breastfeeding be educated on methods to avoid mastitis, and that those who develop mastitis avoid breastfeeding on the affected side until the condition resolves.3

In addition to draining breast milk as thoroughly as possible, antibiotics are often necessary to treat mastitis. Few studies are available to guide the physician in determining when antibiotics are needed, or in selecting antibiotics. If a culture was obtained, results can guide therapy. Because the most common infecting organism is S. aureus, antibiotics that are effective against this organism should be selected empirically. Table 2 lists antibiotics that are commonly used to treat mastitis.11,17,22 The duration of antibiotic therapy is also not well studied, but usual courses are 10 to 14 days.17 A Cochrane review of antibiotic treatment for mastitis in lactating women is currently underway.23

| Amoxicillin/clavulanate (Augmentin), 875 mg twice daily |

| Cephalexin (Keflex), 500 mg four times daily |

| Ciprofloxacin (Cipro),* 500 mg twice daily |

| Clindamycin (Cleocin),* 300 mg four times daily |

| Dicloxacillin (Dynapen, brand no longer available in the United States), 500 mg four times daily |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (Bactrim, Septra),*† 160 mg/800 mg twice daily |

As outpatient infection with methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) becomes increasingly common, physicians need to be aware of the local prevalence and sensitivities of this organism. A recent case report describes MRSA contamination of expressed breast milk and implicates this in the death of a premature infant with sepsis.24 Organisms other than S. aureus have rarely been implicated as the cause of mastitis. These include fungi such as Candida albicans, as well as group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.7,11

Complications

One of the most common complications of mastitis is the cessation of breastfeeding. Mothers should be reminded of the many benefits of breastfeeding and encouraged to persevere. Another potential complication is the development of an abscess, which presents similarly to mastitis except that there is a firm area in the breast, often with fluctuance. An abscess can be confirmed by ultrasonography and should be treated with surgical drainage or needle aspiration, which may need to be repeated. Fluid from the abscess should be cultured, and antibiotics should be administered, as outlined in Table 2.11,17,22 Breastfeeding usually can continue, except if the mother is severely ill or the infant's mouth must occlude the open incision when feeding.20

Because inflammatory breast cancer can resemble mastitis, this condition should be considered when the presentation is atypical or when the response to treatment is not as expected.

Resources

The International Lactation Consultant Association is an organization of board-certified lactation consultants. Its Web site (http://www.ilca.org) lists local lactation consultants worldwide. La Leche League International (http://www.llli.org) has many handouts to assist breastfeeding mothers with common problems (e.g., sore nipples).