Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(6):726-734

This is part I of a two-part article on generalized rashes. Part II, “Diagnostic Approach,” appears in this issue of AFP.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

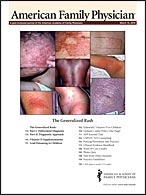

Physicians often have difficulty diagnosing a generalized rash because many different conditions produce similar rashes, and a single condition can result in different rashes with varied appearances. A rapid and accurate diagnosis is critically important to make treatment decisions, especially when mortality or significant morbidity can occur without prompt intervention. When a specific diagnosis is not immediately apparent, it is important to generate an inclusive differential diagnosis to guide diagnostic strategy and initial treatment. In part I of this two-part article, tables listing common, uncommon, and rare causes of generalized rash are presented to help generate an inclusive differential diagnosis. The tables describe the key clinical features and recommended tests to help accurately diagnose generalized rashes. If the diagnosis remains unclear, the primary care physician must decide whether to observe and treat empirically, perform further diagnostic testing, or refer the patient to a dermatologist. This decision depends on the likelihood of a serious disorder and the patient's response to treatment.

Generalized rashes are among the most common conditions seen by primary care physicians,1,2 and the most common reason for new patient visits to dermatologists.3 Diagnostic errors involving generalized rashes are common.4,5 However, accurate diagnosis is important because treatment varies depending on the etiology, and because some rashes can be life-threatening if not treated promptly. Some generalized rashes have distinctive features that allow immediate recognition, such as psoriasis (silvery white scale on the knees and elbows), pityriasis rosea (herald patch), and atopic dermatitis (lichenified skin in flexural areas). But these conditions, like many others, can present with similar appearances and can be mistaken for each other.

It is difficult to comprehensively review generalized rashes because the topic is so broad. Previous reviews have been limited to narrower topics, such as viral exanthems,6 drug eruptions,7 and rashes associated with fever.8,9 Physicians, however, cannot limit their considerations; they must constantly guard against premature closure of the diagnostic process.10 Therefore, a broad perspective is maintained in this article. Generalized rashes that manifest only as purpura or petechiae will not be discussed, with the exception of meningococcemia and Rocky Mountain spotted fever (because these conditions often present initially with nonspecific maculopapular rashes before becoming purpuric). Rashes that primarily affect pregnant women, newborns, immunocompromised persons, and persons living outside North America are also excluded. Part I of this two-part article focuses on differential diagnosis of generalized rashes. Part II focuses on the clinical features that can help distinguish these rashes.11

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

Skin biopsy is helpful in diagnosing the following conditions:

| C | 16, 20, 22, 28, 35, 36, 38, 39 |

Differential Diagnosis

The causes of a generalized rash are numerous, but most patients have common diseases (Table 1).12–26 Many common rashes improve spontaneously or with simple measures, such as discontinuing a medication. Life-threatening rashes are rare in the United States, so they can be easily missed because they are not considered.

| Condition | Key clinical features | Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis | Dry skin; pruritus; erythema; erythematous papules; excoriations; scaling; lichenification; accentuation of skin lines; keys to diagnosis are pruritus, eczematous appearance of lesions, and personal or family history of atopy12 | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Contact dermatitis | Erythema; edema; vesicles; bullae in linear or geometric pattern; common causes include cosmetics, topical medications, metal, latex, poison ivy, textiles, dyes, sunscreens, cement, food, benzocaine, neomycin13; keys to diagnosis are linear or geometric pattern and distribution of lesions | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done,* but it can help exclude other conditions |

| Drug eruption† | Many patterns, but most commonly maculopapular (95% of cases)14; common in patients taking allopurinol (Zyloprim), beta-lactam antibiotics, sulfonamides, anticonvulsants, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, hypoglycemics, and thiazide diuretics, but can occur with almost any drug14; usually appears within 1 to 4 weeks of initiating drug; key to diagnosis is timing of rash appearance in relation to drug use14 | Skin biopsy is usually nonspecific and not often done*15 |

| Erythema multiforme | Round, dusky red lesions that evolve into target (iris) lesions over 48 hours; starts on backs of hands and feet and on extensor surfaces of arms and legs; symmetric; may involve palms, soles, oral mucous membranes, or lips; key to diagnosis is presence of target lesions | Skin biopsy is generally diagnostic and occasionally done; biopsy should be taken from the erythematous (not blistered) portion of the target16 |

| Fifth disease (i.e., erythema infectiosum)† | “Slapped cheek” appearance with sparing of periorbital areas and nasal bridge; unique fishnet pattern; erythema on extremities, trunk, and buttocks; keys to diagnosis in children are slapped cheek appearance and net-like rash, and in adults are arthralgias and history of exposure to affected child | Parvovirus B19 serology; skin biopsy is nonspecific and rarely done* |

| Folliculitis | Multiple small pustules localized to hair follicles on any body surface; key to diagnosis is hair follicle at center of each lesion | Skin biopsy is often diagnostic but not often done* |

| Guttate psoriasis | Pinpoint to 1-cm scaling papules and plaques on trunk and extremities; often preceded by streptococcal pharyngitis 1 to 2 weeks before eruption17; keys to diagnosis are scaling and history of streptococcal pharyngitis17 | Throat culture; antistreptolysin O titer; early skin biopsy may not be diagnostic and is not often done* |

| Insect bites | Urticarial papules and plaques; keys to diagnosis are outdoor exposure (usually) and distribution of lesions where insects are likely to bite | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Keratosis pilaris | Pinpoint follicular papules and pustules on posterolateral upper arms, cheeks, anterior thighs, or buttocks18; keys to diagnosis are upper arm distribution, absence of comedones, and tiny palpable lesions | Skin biopsy can be diagnostic but is not often done* |

| Lichen planus | Violaceous flat-topped papules and plaques; commonly on ankles and wrists; 5 P's (pruritic, planar, polygonal, purple plaques); Wickham striae (reticular pattern of white lines on surface of lesions)19; lacy white buccal mucosal lesions; Koebner phenomenon (development of typical lesions at the site of trauma); keys to diagnosis are purple color and distribution of lesions20 | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and often done |

| Miliaria rubra (i.e., prickly heat, heat rash) | Erythematous nonfollicular papules associated with heat exposure or fever; lesions on back, trunk, neck, or occluded areas; keys to diagnosis are history of heat exposure and distribution of lesions | Skin biopsy can be diagnostic but is not often done* |

| Nummular eczema | Sharply defined, 2- to 10-cm, coin-shaped, erythematous, scaled plaques; lesions on dorsal hands and feet, extensor surfaces of arms and legs, flanks, and hips; key to diagnosis is sharply defined, round, erythematous, scaled lesions | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done,* but it may help exclude other diagnoses |

| Pityriasis rosea | Discrete, round to oval, salmon pink, 5- to 10-mm lesions; “Christmas tree” pattern on back; often (17 to 50%) preceded by solitary 2- to 10-cm oval, pink, scaly herald patch21; keys to diagnosis are oval shape, orientation with skin lines, and distinctive scale | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done,* but it may help exclude other diagnoses; rapid plasma reagin testing is optional to rule out secondary syphilis |

| Psoriasis (plaque psoriasis) | Thick, sharply demarcated, round or oval, erythematous plaques with thick silvery white scale; lesions on extensor surfaces, elbows, knees, scalp, central trunk, umbilicus, genitalia, lower back, or gluteal cleft; positive Auspitz sign (removal of scale produces bleeding points); Koebner phenomenon; keys to diagnosis are distinctive scale and distribution of lesions22 | Skin biopsy can be diagnostic but is not often done* |

| Roseola (i.e., exanthem subitum, sixth disease) | Sudden onset of high fever without rash or other symptoms in a child younger than 3 years; as fever subsides, pink, discrete, 2- to 3-mm blanching macules and papules suddenly appear on trunk and spread to neck and extremities; key to diagnosis is high fever followed by sudden appearance of rash as fever abruptly resolves23 | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Scabies | Discrete, small burrows, vesicles, papules, and pinpoint erosions on fingers, finger webs, wrists, elbows, knees, groin, buttocks, penis, scrotum, axillae, belt line, ankles, and feet; keys to diagnosis are distribution of lesions, intense pruritus, and positive mineral oil mount | Mineral oil mount is routinely done to identify mites or eggs; skin biopsy is usually nonspecific and not often done* |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Erythematous patches with greasy scale; lesions behind ears or on scalp and scalp margins, external ear canals, base of eyelashes, eyebrows, nasolabial folds, central chest, axillae, inframammary folds, groin, and umbilicus; keys to diagnosis are greasy scale and distribution of lesions | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Tinea corporis | Flat, red, scaly lesions progressing to annular lesions with central clearing or brown discoloration; keys to diagnosis are annular lesions with central clearing and positive KOH preparation | KOH preparation is routinely done; skin biopsy can be diagnostic24 but is not often done* |

| Urticaria (i.e., hives) | Discrete and confluent, raised, edematous, round or oval, waxing and waning lesions with large variation in size; may have erythematous border (flare) and pale center (wheal); patient may have history of drug, food, or substance exposure; key to diagnosis is distinctive appearance of edematous lesions | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Varicella† | Vesicles on erythematous papules (“dewdrop on rose petal” appearance); all stages (papules, vesicles, pustules, crusts) are present at the same time and in close proximity; keys to diagnosis are crops of lesions in different stages, systemic illness, and exposure to persons with the infection | Diagnosis is usually clinical, but real-time polymerase chain reaction assay of skin lesion or direct fluorescent antibody testing of skin scrapings could be done25; skin biopsy is often diagnostic but cannot distinguish herpes zoster or herpes simplex, and is not often done* |

| Viral exanthem, nonspecific | Blanchable, red, sometimes confluent macules and papules; may be indistinguishable from drug eruptions26; keys to diagnosis are nonspecific generalized maculopapular rash in a child with systemic symptoms (fever, diarrhea, headache, fatigue) | Skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

Because of the large number of conditions that can manifest as a generalized rash, it is not reasonable to expect physicians to generate a complete differential diagnosis from memory at the point of care. Consulting a list of potential causes allows the physician to narrow the possibilities by noting salient clinical features and test results (Table 112–26, Table 227–39, and Table 340 ). If the diagnosis remains unclear, the physician must decide whether to treat the patient symptomatically, pursue further testing, or consult a dermatologist.

| Condition | Key clinical features | Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Bullous pemphigoid | Generalized bullae, especially on trunk and flexural areas; patient usually older than 60 years27; Nikolsky sign (easy separation of epidermis from dermis with lateral pressure) usually negative | Skin biopsy with direct and indirect immunofluorescence is diagnostic and usually done |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Symmetric, pruritic, urticarial papules and vesicles that are often excoriated and isolated or grouped on extensor surfaces (knees, elbows), buttocks, and posterior scalp; most patients have celiac disease, but it is often asymptomatic; diagnosis is often delayed28 | Skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence is diagnostic and routinely done |

| HIV acute exanthem* | Diffuse, nonspecific, erythematous, maculopapular, nonpruritic lesions29; fever, fatigue, headache, lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, myalgias, and gastrointestinal disturbances | Measurement of quantitative plasma HIV-1 RNA levels (viral load) by polymerase chain reaction30; HIV serology (delay at least 1 month after acute illness); skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

| Id reaction | Follicular papules or maculopapular or vesiculopapular rash involving forearms, thighs, legs, trunk, or face; associated with active dermatitis (e.g., stasis dermatitis) or fungal infection elsewhere | KOH preparation to diagnose dermatophyte infection; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

| Kawasaki disease* | Erythematous rash on hands and feet starting 3 to 5 days after onset of fever in children younger than 8 years (usually younger than 4 years); blanching macular exanthem on trunk, especially groin and diaper area; hyperemic oral mucosa and red, dry, cracked, bleeding lips | CBC to detect elevated white blood cell and platelet counts; measurement of C-reactive protein level and erythrocyte sedimentation rate31; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

| Lupus (subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus) | Papulosquamous or annular pattern, mainly on trunk and sun-exposed face and arms; can be drug induced32 | Antinuclear antibody testing; skin biopsy with direct immunofluorescence is diagnostic and often done |

| Lyme disease* | Erythema migrans at site of tick bite, progressing to generalized macular lesions on proximal extremities, chest, and creases (median lesion size, 15 cm); history of outdoor activities; most common in northeastern U.S. seaboard, Minnesota, and Wisconsin33 | Serology; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

| Meningococcemia* | Nonblanching petechiae and palpable purpura, which may have gunmetal gray necrotic centers34; usually spares palms and soles; may start as erythematous papules or pink macules | Positive cultures of blood, lesions, and cerebrospinal fluid; positive buffy coat Gram stain; skin biopsy is usually nonspecific and not often done† |

| Mycosis fungoides (i.e., cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) | Flat erythematous macules evolving into red scaly plaques with indistinct edges and poikiloderma (atrophy, white and brown areas, telangiectasia); can present as erythroderma (Sézary syndrome); diagnosis is often delayed; often confused with eczema35 | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and routinely done |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever* | 2- to 6-mm macules that spread centrally from wrists and ankles and that progress to papules and petechiae; often involves palms and soles; fever, severe headache, photophobia, myalgias, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting; history of outdoor activities in endemic area (e.g., Oklahoma, Tennessee, Arkansas, southern Atlantic states) | Serology; skin biopsy with direct fluorescent antibody testing is diagnostic and often done, if available36 |

| Scarlet fever* | Blanching sandpaper-like texture follows streptococcal pharyngitis or skin infection; Pastia lines (petechiae in antecubital and axillary folds); fever, vomiting, headache, and abdominal pain; most common in children | Antistreptolysin O titer; throat culture; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

| Secondary syphilis* | Variable morphology, but usually red-brown scaly papules with involvement of the palms and soles; oral and genital mucosa also commonly affected | Positive syphilis serology (usually done); skin biopsy can be nonspecific and is not often done† |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome* | Starts with painful, tender sandpaper-like erythema favoring flexural areas, and progresses to large, flaccid bullae37; positive Nikolsky sign; most common in children younger than 6 years | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and routinely done to distinguish from toxic epidermal necrolysis, which is rare in infancy and childhood; frozen section biopsy should be considered; eyes, nose, throat, and bullae should be cultured for Staphylococcus aureus |

| Stevens-Johnson syndrome* Toxic epidermal necrolysis* | Stevens-Johnson syndrome: vesiculobullous lesions on the eyes, mouth, genitalia, palms, and soles; usually drug induced Toxic epidermal necrolysis: life-threatening condition with diffuse erythema, fever, and painful mucosal lesions; positive Nikolsky sign | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and routinely done for toxic epidermal necrolysis; frozen section biopsy should be considered38 |

| Sweet syndrome (i.e., acute febrile neutrophilic dermatosis) | Red, tender papules that evolve into painful erythematous plaques and annular lesions on upper extremities, head, neck, backs of hands, and back; most common in middle-aged and older women | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and routinely done39 |

| Toxic shock syndrome* | Diffuse erythema (resembling sunburn); fever, malaise, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, hypotension, diarrhea, and confusion; conjunctival injection, mucosal hyperemia (oral or genital); late desquamation, especially on palms and soles; most common in menstruating women or postoperative patients | CBC to detect thrombocytopenia; blood cultures; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done† |

Patients with acute generalized maculopapular rashes and no systemic symptoms are often treated symptomatically without a definitive diagnosis. If the rash does not resolve spontaneously, skin biopsy and blood testing (e.g., serologies, complete blood count) may be indicated. There are no widely accepted guidelines that address indications for skin biopsy, but Table 112–26, Table 227–39, and Table 340 include common practices. The patient should be referred to a dermatologist if the rash is progressive or does not resolve with observation or empiric treatment. For example, mycosis fungoides (cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) mimics eczema in its early stages and is rarely diagnosed correctly at initial presentation.41 Reevaluation and possible referral are imperative in chronic eczematous conditions that do not respond to therapy.

| Condition | Key clinical features | Tests |

|---|---|---|

| Lichen nitidus | 1- to 3-mm, skin-colored, raised, flat-topped papules on trunk, flexor surfaces of extremities, dorsal hands, or genitalia | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and often done |

| Pityriasis lichenoides | 2- to 10-mm, round or oval, red-brown papules progressing to hemorrhagic lesions on trunk, thighs, or upper arms | Skin biopsy is diagnostic and routinely done |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris | Red or orange follicular papules on fingers, elbows, knees, trunk, or scalp; often mistaken for psoriasis; characterized by “skip areas” of normal skin | Skin biopsy is occasionally nonspecific but can help exclude other conditions, and is routinely done |

| Rickettsialpox | Initial lesion, which may not be noticed by patient, begins as papule and evolves to vesicle, then crusts; generalized maculopapular vesicular exanthem can involve palms and soles; most common in large cities40 | Serology (immunoglobulin G for Rickettsia rickettsii and Rickettsia akari); biopsy with direct fluorescent antibody testing may be diagnostic but is not often done* |

| Rubella† | Round, pink macules and papules starting on forehead, neck, and face, then spreading to trunk and extremities, including palms and soles | Serology; skin biopsy is nonspecific and not often done* |

| Rubeola | Maculopapular purple-red lesions that may become confluent; start on face and behind ears and at anterior hairline; Koplik spots (i.e., tiny red or white spots with red halo on buccal mucosa) | Serology; skin biopsy is usually nonspecific and not often done* |

It is important to look beyond the appearance of the rash itself and search for clues from the patient's history, physical examination, laboratory tests, and skin biopsy. Because of busy schedules and perceived patient expectations, physicians often feel pressured to quickly arrive at a diagnosis. However, unless the diagnosis is obvious, it is usually more productive to start with a differential diagnosis that includes all reasonable possibilities.4,42,43 Before making a final diagnosis, the physician could also refer to a list of rashes that are often confused with each other (Table 4).4,8,26

| Condition | Similar rashes (distinguishing features) |

|---|---|

| Atopic dermatitis | Contact dermatitis (not associated with dry skin) |

| Keratosis pilaris (nonpruritic, involves posterolateral upper arms) | |

| Mycosis fungoides (lesion borders sharper, fixed size and shape) | |

| Psoriasis (well-defined plaques, silvery white scale, involves extensor surfaces) | |

| Scabies (involves genitalia, axillae, finger webs) | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis (nonpruritic, greasy scale, characteristic distribution) | |

| Contact dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis (symmetric distribution, history of hay fever or asthma, flexural areas, hyperlinear palms, family history, not limited to area of exposure, dry skin and itching precede skin lesions rather than follow them) |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis (vesicles on extensor surfaces, enteropathy, burning pain) | |

| Psoriasis (patches on knees, elbows, scalp, and gluteal cleft; pitted nails) | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis (greasy scale on eyebrows, nasolabial folds, or scalp) | |

| Drug eruption (morbilliform) | Erythema multiforme (target lesions) |

| Viral exanthem (more common in children, less intense erythema and pruritus, less likely to be dusky red, more focal systemic symptoms, less likely to be polymorphic, less likely to be associated with eosinophilia)8,26 | |

| Pityriasis rosea | Drug eruption (no scale, lesions coalesce) |

| Erythema multiforme (target lesions) | |

| Guttate psoriasis (thicker scale, history of streptococcal pharyngitis) | |

| Lichen planus (violaceous, involves wrists and ankles) | |

| Nummular eczema (larger round [not oval] lesions, do not follow skin lines) | |

| Psoriasis (thick white scale, involves extensor surfaces) | |

| Secondary syphilis (positive serology; involves palms and soles) | |

| Tinea corporis (positive KOH preparation, scale at peripheral border of lesions rather than inside border) | |

| Viral exanthem (no scale, lesions coalesce) | |

| Psoriasis | Atopic dermatitis (atopic features, flexural areas, lichenification) |

| Lichen planus (violaceous, minimal scale, involves wrists and ankles) | |

| Mycosis fungoides (lesion borders less distinct) | |

| Pityriasis rubra pilaris (islands of normal skin) | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis (greasy scale, involves anterior face) | |

| Secondary syphilis (red-brown lesions on palms and soles) | |

| Tinea corporis (thinner peripheral scale, positive KOH preparation) | |

| Seborrheic dermatitis | Atopic dermatitis (nongreasy scale, atopic history, pruritic) |

| Psoriasis (silver scale, sharply demarcated lesions on extensor surfaces of extremities; involvement of scalp commonly extends onto forehead, whereas seborrheic dermatitis of scalp stops at scalp margin) |