A more recent article on chronic constipation in adults is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2011;84(3):299-306

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Constipation is traditionally defined as three or fewer bowel movements per week. Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age, inactivity, low caloric intake, low-fiber diet, low income, low educational level, and taking a large number of medications. Chronic constipation is classified as functional (primary) or secondary. Functional constipation can be divided into normal transit, slow transit, or outlet constipation. Possible causes of secondary chronic constipation include medication use, as well as medical conditions, such as hypothyroidism or irritable bowel syndrome. Frail older patients may present with nonspecific symptoms of constipation, such as delirium, anorexia, and functional decline. The evaluation of constipation includes a history and physical examination to rule out alarm signs and symptoms. These include evidence of bleeding, unintended weight loss, iron deficiency anemia, acute onset constipation in older patients, and rectal prolapse. Patients with one or more alarm signs or symptoms require prompt evaluation. Referral to a subspecialist for additional evaluation and diagnostic testing may be warranted.

Constipation is one of the most common chronic gastrointestinal disorders in adults.1,2 In a 1997 epidemiology of constipation study that surveyed 10,018 persons, 12 percent of men and 16 percent of women met criteria for constipation.3 Annually, constipation accounts for 2.5 million physician visits and 92,000 hospitalizations in the United States.4–6 Constipation compromises quality of life, social functioning, and the ability to perform activities of daily living.7,8 These factors are important predictors of constipation-associated health care use and resultant health care costs.6,9 This article reviews an approach for the evaluation of chronic constipation in adults.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence Rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| A history and physical examination should be performed in patients with constipation to identify alarm signs or symptoms. | C | 46 |

| Routine use of blood tests, radiography, or endoscopy in patients with constipation who do not have alarm signs or symptoms is not recommended. | C | 46, 49 |

| Patients with alarm signs or symptoms should undergo endoscopy to rule out malignancy. | C | 53 |

| The initial management of noncomplicated constipation should include a high-fiber diet, increased water intake, and exercise. | B | 46, 54, 55 |

| Biofeedback is recommended for treating symptoms of pelvic floor dysfunction. | B | 34 |

Definition

Traditionally, physicians have defined constipation as three or fewer bowel movements per week. Having fewer bowel movements is associated with symptoms of lower abdominal discomfort, distension, or bloating.10 However, patients tend to define constipation differently than physicians, and describe it in a variety of ways. In a self-reported survey of 1,028 young adults, 52 percent defined constipation as straining, 44 percent as hard stools, 32 percent as infrequent stools, and 20 percent as abdominal discomfort.11 The Rome III diagnostic criteria are widely used in research and provide a more complete and reproducible definition of functional constipation (Table 1).12 Frequency of bowel movements is only one of the criteria.

| Must include two or more of the following: | |

| Straining during at least 25 percent of defecations | |

| Lumpy or hard stools in at least 25 percent of defecations | |

| Sensation of incomplete evacuation for at least 25 percent of defecations | |

| Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage for at least 25 percent of defecations | |

| Manual maneuvers to facilitate at least 25 percent of defecations (e.g., digital evacuation, support of the pelvic floor) | |

| Fewer than three defecations per week | |

| Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives | |

| There are insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome | |

Risk Factors

Risk factors for constipation include female sex, older age,13 inactivity, low caloric intake, low-fiber diet,14,15 taking a large number of medications,16 low income, and low educational level.13,16–22 The incidence of constipation is three times higher in women,13 and women are twice as likely as men to schedule physician visits for constipation.4,23,24 Studies have shown that bowel transit time in women tends to be slower than in men, and many women experience constipation during their menstrual period.25–27 Constipation is 1.3 times more likely to occur in nonwhites than in whites, and is considerably more common in families of low socioeconomic status.23 In the United States, constipation also has a distinct geographic distribution. Medicare beneficiary data suggest that in addition to low socioeconomic status, environmental risk factors for constipation may include living in rural areas and in colder temperatures.24

A study using data from a general practice research database of more than 20,000 persons in the United Kingdom found that female sex, older age, multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism, and dementia were associated with constipation.16 The medications most strongly associated with constipation included aluminum-containing antacids, diuretics, opioids, antidepressants, antispasmodics, and anticonvulsants. Beta blockers and calcium channel blockers were associated with constipation, but were not independent risk factors.16

Types of Constipation

Chronic constipation can be divided into two categories: functional (primary) and secondary. Functional constipation is defined by the Rome III diagnostic criteria (Table 112 ) and can be further divided into normal transit, slow transit, and outlet constipation.28 Secondary constipation is caused by medical conditions or medication use. Table 2 lists selected causes of secondary constipation.17

| Medications | |

| Common | |

| Antacids, especially with calcium | |

| Iron supplements | |

| Opioids | |

| Less common | |

| Anticholinergic agents | |

| Antidiarrheal agents | |

| Antihistamines | |

| Antiparkinsonian agents | |

| Antipsychotics | |

| Calcium channel blockers | |

| Calcium supplements | |

| Diuretics | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | |

| Sympathomimetics | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | |

| Medical conditions | |

| Common | |

| Cerebrovascular disease | |

| Depression | |

| Diabetes mellitus | |

| Hypothyroidism | |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Less common | |

| Anal fissures | |

| Autonomic neuropathy | |

| Cognitive impairment | |

| Colon cancer | |

| Hypercalcemia | |

| Hypokalemia | |

| Hypomagnesemia | |

| Immobility | |

| Multiple sclerosis | |

| Parkinson disease | |

| Spinal cord injury | |

NORMAL TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

Normal transit constipation is defined as a perception of constipation on patient self-report; however, stool movement is normal throughout the colon.14,29 Other symptoms reported by patients with normal transit constipation include abdominal pain and bloating. Normal transit constipation has been associated with increased psychosocial stress,14 and usually responds to medical therapy, such as fiber supplementation or laxatives.30

SLOW TRANSIT CONSTIPATION

Slow transit constipation is defined as prolonged transit time through the colon. This can be confirmed with radiopaque markers that are delayed on motility study.31 A prolonged colonic transit time is defined as more than six markers still visible on a plain abdominal radiograph taken 120 hours after ingestion of one Sitzmarks capsule containing 24 radiopaque markers.15 Patients with slow transit constipation have normal resting colonic motility, but do not have the increase in peristaltic activity that should occur after meals. In addition, the administration of bisacodyl (Dulcolax) and cholinergic agents does not cause an increase in peristaltic waves as it does in persons without constipation.32,33 A case series of 64 patients found that slow transit constipation was an important cause of constipation in young women with very infrequent bowel movements.29 Typical symptoms of slow transit constipation include an infrequent “call to stool,” bloating, and abdominal discomfort. Patients with severe slow transit constipation tend not to respond to fiber supplementation or laxatives, although one clinical trial demonstrated a response to biofeedback.29,30,34

OUTLET CONSTIPATION

Outlet constipation, also known as pelvic floor dysfunction, is defined as incoordination of the muscles of the pelvic floor during attempted evacuation.35 Outlet constipation is not caused by muscle or neurologic pathology, and most patients have normal colonic transit.35–37 In patients with outlet constipation, stool is not expelled when it reaches the rectum. Common features include prolonged or excessive straining, soft stools that are difficult to pass, and rectal discomfort. It is not uncommon for patients to require manual aid to evacuate stool from the rectum. The exact etiology of outlet constipation remains unclear. Defecation disorders do not respond to traditional medical treatment, but may respond to biofeedback and relaxation training.38

CONSTIPATION IN OLDER ADULTS

Constipation is not a normal part of aging. A review of the literature found that the prevalence of constipation peaks after 70 years of age, reaching between 8 and 43 percent, depending on the population studied.13 One study showed that 7 percent of patients were constipated within three months of admission to a nursing home.39 Most older persons perceive constipation as straining during defecation and difficulty in evacuation, rather than decreased frequency of bowel movements.40–42 In community-dwelling adults older than 65 years, about 20 percent have rectal outlet delay with need to self-evacuate.20 Other causes of functional constipation in older adults may result from autonomic neuropathies, such as diabetes mellitus and Parkinson disease, or from use of medications, such as opioids and anticholinergics.43 A prospective study in nursing home residents found that independent risk factors for constipation included poor consumption of fluids, pneumonia, Parkinson disease, immobility, use of more than five medications, dementia, hypothyroidism, white race, allergies, arthritis, and hypertension.39 Frail older persons may not be able to report bowel-related symptoms because of communication or cognitive impairment. They also may have impaired rectal sensation and inhibited urge to evacuate, and therefore may not be aware of fecal impaction. As a result, these patients may experience nonspecific symptoms, such as delirium, anorexia, and functional decline.44,45

Important presentations of constipation in older persons include fecal impaction and fecal incontinence secondary to paradoxical diarrhea.40 Patients with fecal impaction may present with nonspecific symptoms of clinical deterioration, or more specific symptoms, such as anorexia, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Paradoxical diarrhea may occur when liquid stools from the proximal colon bypass the impacted stool. The impaction can lead to diminished rectal sensation and resultant fecal incontinence. Fecal impaction can cause bowel obstruction and ulceration. Risk factors for fecal impaction include prolonged immobility, cognitive impairment, spinal cord disorders, and colonic neuromuscular disorders. Excessive straining from constipation can also lead to hemorrhoids, anal fissures, and rectal prolapse. In some cases, straining can cause syncope or cardiac ischemia.45

Diagnostic Evaluation

| Finding | Possible cause | |

|---|---|---|

| History | ||

| Bloating, cramping | Irritable bowel syndrome | |

| Hematochezia | Colon cancer, diverticulosis, inflammatory bowel disease | |

| New-onset constipation in older patients | Colon cancer | |

| Prolonged straining, digital evacuation | Pelvic floor dysfunction | |

| Weight loss of more than 10 lb (4.5 kg) | Colon cancer | |

| Physical examination | ||

| Lack of anal wink | Sacral nerve pathology | |

| Lack of pelvic lift during DRE | Pelvic floor dysfunction | |

| Leakage of stool on DRE | Fecal impaction, patulous anus, rectal prolapse | |

| Pain on DRE | Anal fissure, hemorrhoids | |

| Test results | ||

| Elevated serum calcium levels, low serum potassium levels, low serum magnesium levels | Metabolic causes | |

| Elevated serum ferritin levels (iron deficiency anemia) | Colon cancer | |

| Elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone level | Hypothyroidism | |

| Positive fecal occult blood test | Colon cancer | |

HISTORY

The physician should begin by inquiring about which features the patient finds most distressing. If the patient feels pain, bloating, or intestinal cramping between bowel movements, these could be symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (Table 412 ). A history of prolonged and excessive straining, especially with soft stools, or a need for digital manipulation to pass stools suggests pelvic floor dysfunction.

| Recurrent abdominal pain or discomfort* at least three days per month in the past three months associated with two or more of the following: | |

| Improvement with defecation | |

| Onset associated with a change in frequency of stool | |

| Onset associated with a change in form (appearance) of stool | |

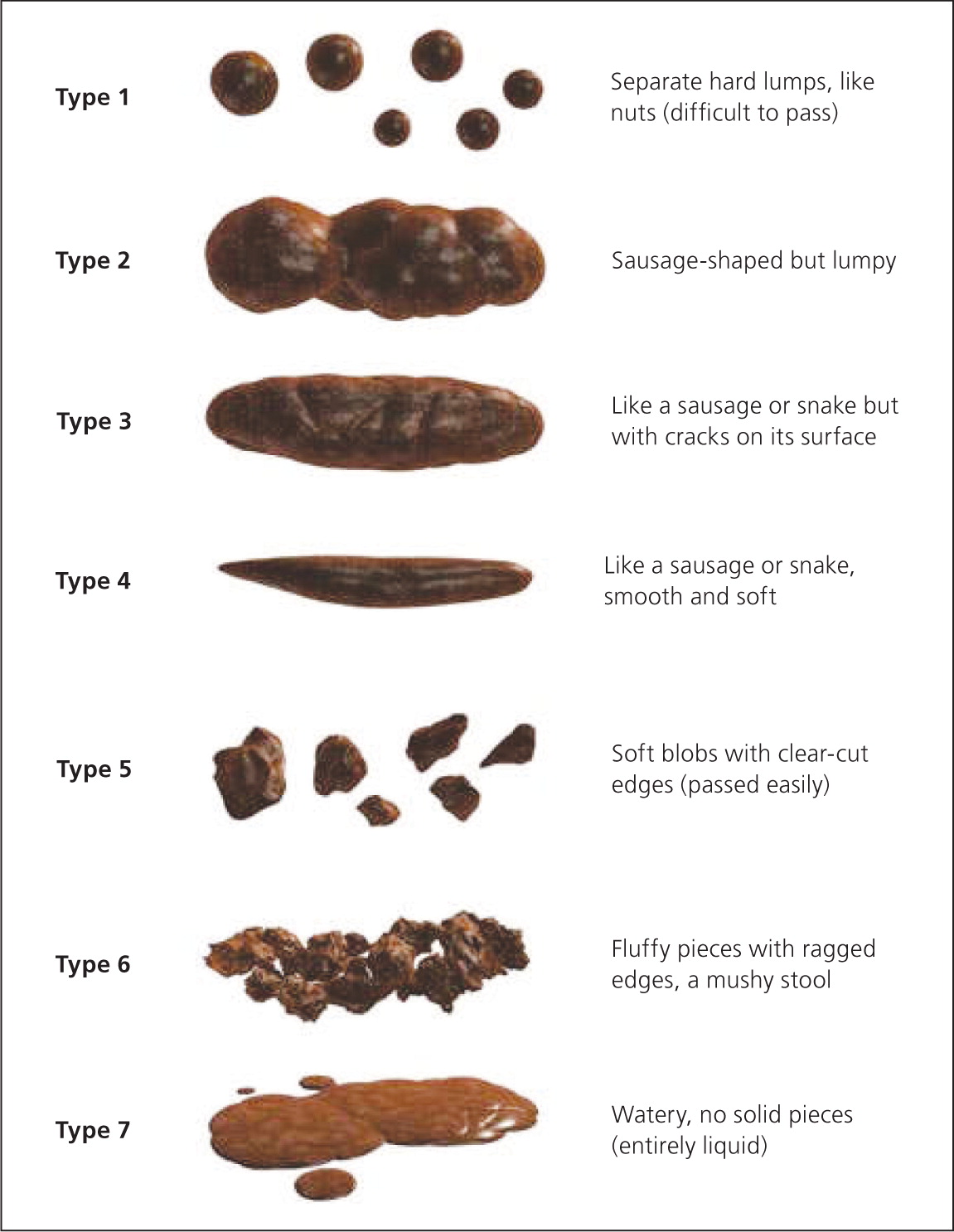

Additional questions should focus on how often the patient feels the need to have a bowel movement, and whether he or she feels a sense of incomplete evacuation. It is important to remind the patient that after a complete evacuation, it takes several days for accumulation that produces a normal fecal mass development. It is useful to ask if the patient is using laxatives, and if so, at what dosage. Physicians should also ask about other treatments being used, including complementary and alternative medicine therapies. Additionally, the patient should be asked to describe the stool caliber. The Bristol Stool Scale is a useful tool to assess stool type and to tailor and monitor treatment (Figure 1).47

In older patients, the history must include asking about medication use, including over-the-counter medications, and performing a nutritional assessment that evaluates the patient's ability to chew and swallow. If clinically indicated, consider evaluating the patient for cognitive impairment and depression.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should include an abdominal and rectal examination, looking for signs of anemia, weight loss, abdominal masses, liver enlargement, or a palpable colon. The perineum should be inspected for hemorrhoids, skin tags, fissures, rectal prolapse, or anal warts. Ask the patient to strain as if having a bowel movement, and look for leakage of stool secondary to fecal impaction, rectal prolapse, or a patulous anus. The next step is to test the anal wink reflex. This is done using a cotton pad or a cotton-tipped applicator in all four quadrants around the anus. The absence of an anal contraction may indicate sacral nerve pathology.

The examination should be completed with a digital rectal examination. Palpation should not elicit pain; the presence of pain with gentle palpation suggests the presence of an anal fissure. Further palpation should assess the resting sphincter tone before assessing all walls of the rectum for masses and fecal impaction, especially in patients older than 40 years. To test for pelvic floor dysfunction, the patient should be asked to strain to attempt to expel the examiner's finger. A normal response is relaxation of the anal sphincter and puborectalis muscle with a 1- to 3.5-cm descent of the perineum. In addition, when the patient contracts the pelvic floor muscles, there should be a lift to the pelvic floor. The absence of these findings suggests pelvic floor dysfunction.48

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

Diagnostic tests (e.g., blood tests, radiography, endoscopy) are not routinely recommended in the initial evaluation of a patient with chronic constipation in the absence of alarm signs or symptoms.46,49 However, if the history and physical examination elicit symptoms of organic disease, such as hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to obtain further diagnostic tests. Physicians should also be alert for red flags, such as hematochezia, unintended weight loss of 10 lb (4.5 kg) or more, a family history of colon cancer, iron deficiency anemia, positive fecal occult blood tests, or acute onset of constipation in an older patient.46,50–52 If one or more of these features are present, endoscopic evaluation may be necessary to rule out malignancy or other serious conditions.53 The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy published guidelines in 2005 on the use of endoscopy in the management of constipation (Table 5).53 Note that colonoscopy is not routinely recommended for all patients with constipation.

| Age older than 50 years with no previous colorectal cancer screening |

| Before surgery for constipation |

| Change in stool caliber |

| Heme-positive stools |

| Iron deficiency anemia |

| Obstructive symptoms |

| Recent onset of constipation |

| Rectal bleeding |

| Rectal prolapse |

| Weight loss |

If the patient has symptoms of outlet constipation or has not responded to reasonable laxative therapy, testing for pelvic floor dysfunction is warranted. This is usually done in specialty centers by confirming inappropriate contraction or failure of pelvic floor muscle relaxation while attempting to defecate; radiography, manometry, or electromyography may be used.38

Initial Management

Figure 2 provides an algorithm for the initial management of functional constipation. After ruling out secondary causes of constipation and determining that diagnostic testing is unnecessary, the physician should encourage lifestyle modification, which includes a high-fiber diet, exercise, and increased water intake.46,54,55 There are conflicting data about the benefits of fluid intake and exercise in relieving constipation. However, even though not statistically significant, a high-fiber diet has shown a decrease in abdominal pain from constipation in many patients.15 In patients with pelvic floor dysfunction, biofeedback therapy has shown a success rate of 35 to 90 percent.34,56

If the patient's constipation does not respond to lifestyle modifications and fiber, an osmotic agent such as magnesium hydroxide or lactulose may help. If osmotic agents do not work, the next step is polyethylene glycol (Miralax), which hydrates the stool without causing electrolyte shifts. If there is still no response, referral to a subspecialist for further workup and management is appropriate. This may include additional pharmacotherapy, endoscopy, anorectal manometry, balloon expulsion testing, defecography, and colon transit testing.