Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(6):430-436

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Occult gastrointestinal bleeding is defined as gastrointestinal bleeding that is not visible to the patient or physician, resulting in either a positive fecal occult blood test, or iron deficiency anemia with or without a positive fecal occult blood test. A stepwise evaluation will identify the cause of bleeding in the majority of patients. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy will find the bleeding source in 48 to 71 percent of patients. In patients with recurrent bleeding, repeat EGD and colonoscopy may find missed lesions in 35 percent of those who had negative initial findings. If a cause is not found after EGD and colonoscopy have been performed, capsule endoscopy has a diagnostic yield of 61 to 74 percent. Deep enteroscopy reaches into the mid and distal small bowel to further investigate and treat lesions found during capsule endoscopy or computed tomographic enterography. Evaluation of a patient who has a positive fecal occult blood test without iron deficiency anemia should begin with colonoscopy; asymptomatic patients whose colonoscopic findings are negative do not require further study unless anemia develops. All men and postmenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia, and premenopausal women who have iron deficiency anemia that cannot be explained by heavy menses, should be evaluated for occult gastrointestinal bleeding. Physicians should not attribute a positive fecal occult blood test to low-dose aspirin or anticoagulant medications without further evaluation.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding may be classified as overt, obscure, or occult. Overt GI bleeding is visible, such as hematemesis (bloody or coffee-ground emesis), hematochezia (the presence of blood and blood clots in the feces), or melena (black tarry stools). Obscure GI bleeding refers to recurrent bleeding in which a source is not identified on upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, or small bowel radiography. Obscure bleeding may be either overt or occult, with the source of bleeding often found in the small bowel. Occult bleeding is not visible to the patient or physician. This review focuses on the causes and diagnostic investigation of occult GI bleeding, manifested as a positive fecal occult blood test (FOBT) or iron deficiency anemia with or without a positive FOBT.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Patients who have a positive FOBT without iron deficiency anemia should be evaluated with colonoscopy. If colonoscopy is negative, asymptomatic patients do not require further studies unless anemia develops. | C | 4, 8, 10, 24 |

| A positive FOBT should not be attributed to low-dose aspirin or anticoagulation without further GI evaluation. | C | 4, 8, 10, 24 |

| Premenopausal women who have iron deficiency anemia that cannot be explained by heavy menses, or those who have GI symptoms, should be evaluated for a GI cause. | C | 4, 8, 10 |

| Men and postmenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia should undergo progressive evaluation for GI blood loss with colonoscopy, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, and capsule endoscopy, as clinically indicated. | C | 4, 8, 10 |

Etiology

In a review of five prospective studies of upper endoscopy and colonoscopy in patients with occult GI bleeding, 20 to 30 percent of patients had a colorectal source, whereas 29 to 56 percent had an upper GI tract source. No source was found in 29 to 52 percent of patients. Synchronous lesions, or simultaneous sources of occult bleeding in the upper GI tract and the colon, were found in 1 to 17 percent of patients.4 Colonic lesions include colon cancer, colon polyps, vascular ectasias, and colitis. Causes of occult bleeding in the upper GI tract include esophagitis, Cameron ulcers (a linear erosion in a hiatal hernia), gastric and duodenal ulcers, vascular ectasias, gastric cancer, and gastric antral vascular ectasia (Tables 14 and 25 ). A small bowel source is likely in a high percentage of patients with recurrent bleeding and negative findings on esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and colonoscopy.

| Findings on EGD and colonoscopy | Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Colorectal source | 20 to 30 | |

| Angiodysplasia | 1 to 9 | |

| Colitis | 1 to 2 | |

| Colon cancer | 5 to 11 | |

| Polyps (adenomas) | 5 to 14 | |

| Upper source | 29 to 56 | |

| Angiodysplasia | 1 to 8 | |

| Celiac disease | 0 to 6 | |

| Duodenal ulcer | 1 to 11 | |

| Esophagitis | 6 to 18 | |

| Gastric cancer | 1 to 4 | |

| Gastric ulcer | 4 to 6 | |

| Gastritis | 3 to 16 | |

| Synchronous lesions (lesions found in both upper GI tract and colon) | 1 to 17 | |

| No source found | 29 to 52 | |

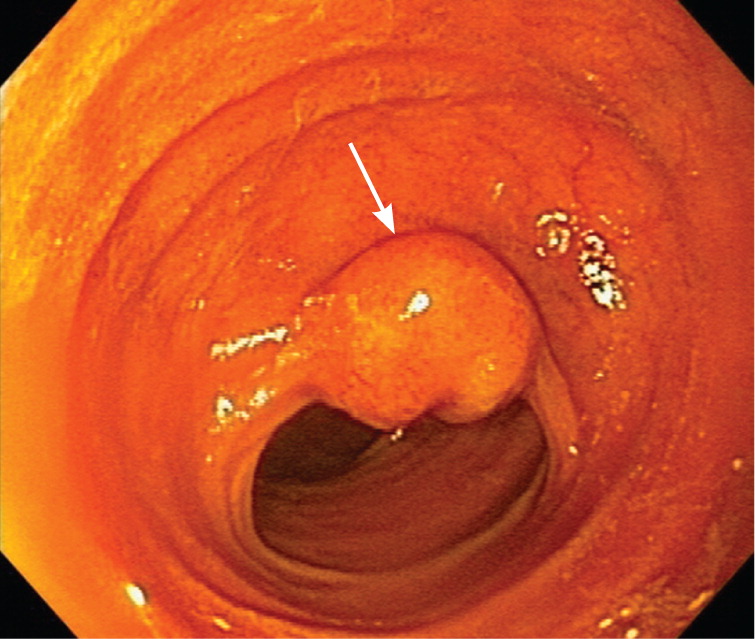

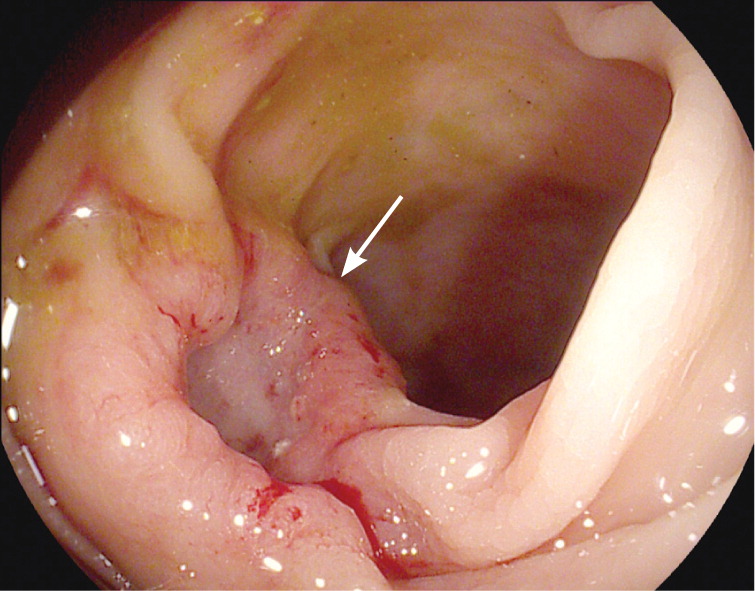

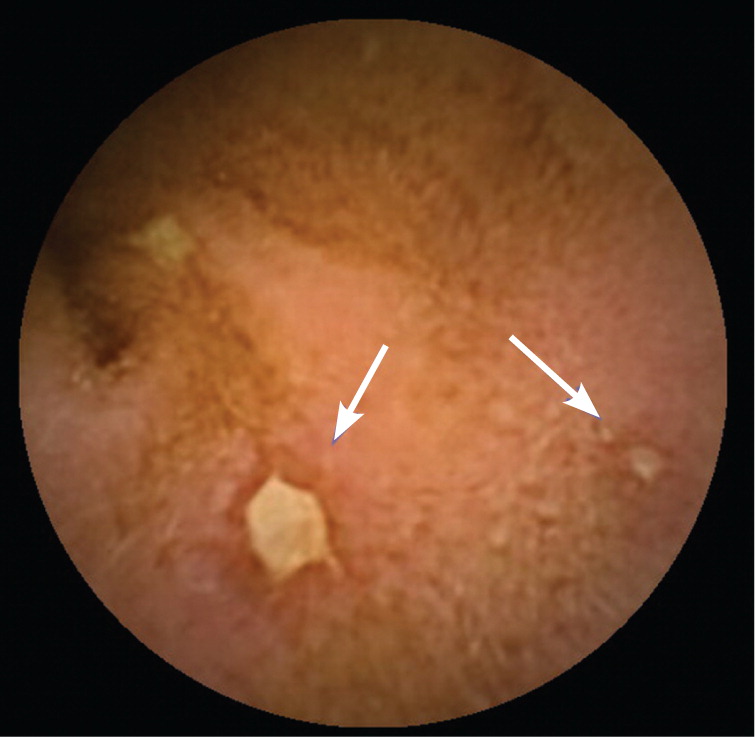

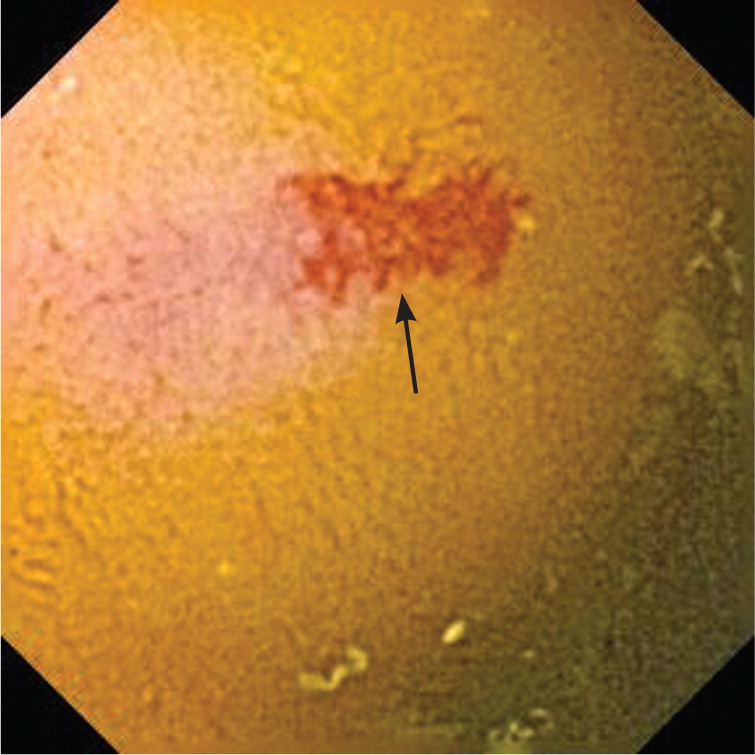

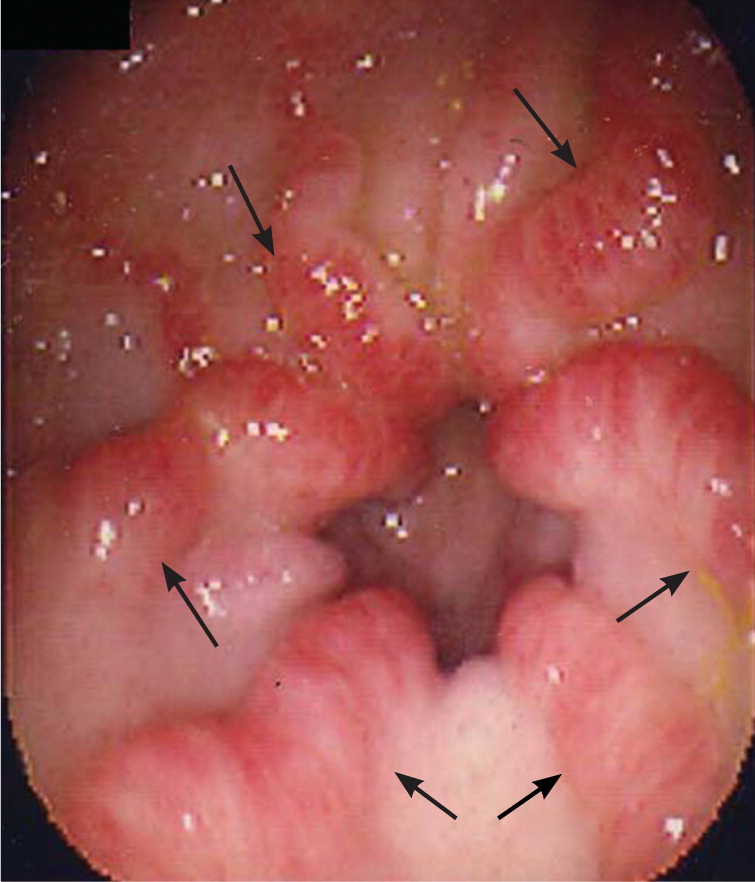

In patients younger than 40 years, small bowel tumors are the most common cause of occult GI bleeding; other causes include celiac disease6 and Crohn disease.5 In patients older than 40 years, vascular ectasias and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug–induced ulcers are the most common causes (Figures 1 through 5). However, celiac disease remains a possible cause in symptomatic7 and asymptomatic8 adults older than 50 years. Less common causes of occult GI bleeding include infections (e.g., hookworm) and long-distance running. Researchers hypothesize that long-distance running induces GI blood loss because of transient intestinal ischemia from decreased splanchnic perfusion during exercise.9

History and Physical Examination

A targeted history and physical examination should be performed. A history of GI bleeding, surgery, or pathology may reveal important diagnostic clues. Unintentional weight loss suggests a malignancy. Abdominal pain with aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use suggests ulcerative mucosal injury. Anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications may precipitate bleeding in an undiagnosed lesion. A family history of GI bleeding may suggest hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (associated with vascular lesions on the lips, tongue, or palms) or blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (a syndrome with venous malformations in the GI tract, soft tissues, and skin). A history of gastric bypass surgery may suggest impaired iron absorption.5 A history of liver disease or stigmata of liver disease suggests portal hypertensive gastropathy or colopathy. Other helpful physical examination findings that could indicate the presence of an underlying condition include dermatitis herpetiformis (celiac disease); erythema nodosum (painful erythematous nodules seen in Crohn disease); an atrophic tongue and brittle, spoon-shaped nails (Plummer-Vinson syndrome); hyperextensible joints and ocular and dental abnormalities (Ehlers-Danlos syndrome); and freckles on the lips and in the mouth (Peutz-Jeghers syndrome).4

Diagnostic Studies

Multiple diagnostic procedures are available to investigate the GI tract in patients with occult bleeding. The choice and sequence of procedures will depend on clinical suspicion and any associated symptoms. Upper GI bleeding (identified as the source of bleeding proximal to the ampulla of Vater) can be detected by EGD. Proximal small bowel bleeding can be detected with push enteroscopy, which reaches the proximal jejunum. Bleeding of the mid and distal small bowel can be detected with capsule endoscopy, deep enteroscopy, and computed tomographic (CT) enterography. Lower GI bleeding (colonic bleeding) can be detected with colonoscopy.10 Intraoperative enteroscopy remains an option for those rare patients who have recurrent bleeding from a source not yet identified with the previously mentioned methods. Small bowel barium studies have a very low yield and have been largely replaced by capsule endoscopy.

EGD and colonoscopy will find the bleeding source in 48 to 71 percent of patients.4 In patients with recurrent bleeding, repeat EGD and colonoscopy may find missed lesions in 35 percent of those who had negative initial findings.4 If a cause is not found after EGD and colonoscopy have been performed, capsule endoscopy has a diagnostic yield of 63 to 74 percent.10

CAPSULE ENDOSCOPY

Wireless capsule endoscopy is a noninvasive method to evaluate the entire length of the small bowel. Capsule endoscopy can identify vascular ectasias, ulcers, and masses in the small bowel in patients with occult GI bleeding.11 In a meta-analysis of 14 studies, the diagnostic yield of capsule endoscopy was superior to push enteroscopy (63 versus 28 percent) and barium studies (42 versus 6 percent).12 The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of capsule endoscopy in obscure GI bleeding were 95, 75, 95, and 86 percent, respectively, without the high rates of morbidity and mortality associated with intraoperative enteroscopy.13 Complications related to capsule endoscopy are rare and include capsule retention (occurring in less than 1 percent of patients who do not have Crohn disease).14

Two wireless capsule endoscopy systems are available in the United States: the Endo Capsule (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.) and the PillCam SB II (Given Imaging Ltd., Duluth, Ga.). Both capsules measure 11 mm × 26 mm and capture two images per second. The diagnostic yields of each system are similar, ranging from 55 to 74 percent.15 Limitations of capsule endoscopy include lack of therapeutic capability and poor visualization in the periampullary region. Videos depicting capsule endoscopy may be viewed at:

DEEP ENTEROSCOPY

Push enteroscopy using longer endoscopes called enteroscopes can evaluate the GI tract to the proximal jejunum. However, with the availability of deep enteroscopy, which typically can reach the mid and distal small bowel, the use of push enteroscopy has diminished significantly. Currently, there are three deep enteroscopy systems approved in the United States: the Double Balloon Endoscopy System (Fujifilm Medical Systems, Stamford, Conn.), the Single Balloon Enteroscope System (Olympus America, Inc., Center Valley, Pa.), and the Endo-Ease Discovery SB small bowel enteroscope or spiral enteroscope (Gyrus ACMI, Inc., Southborough, Mass.). Double-balloon enteroscopy uses two balloons (one on the overtube and one at the end of the enteroscope). Single-balloon enteroscopy uses one balloon at the end of the enteroscope. Spiral enteroscopy uses an overtube with raised helices over an enteroscope, which is rotated clockwise into the small bowel. All three systems permit therapeutic interventions such as coagulation, polypectomy, or presurgical tattooing of lesions.

Deep enteroscopy may be performed via the oral (antegrade) or anal (retrograde) route. Lesions noted in the proximal two-thirds of the small bowel transit time on capsule endoscopy generally may be reached orally. Lesions noted in the distal one-third of the small bowel transit time on capsule endoscopy are approached anally.

In eight studies of double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure GI bleeding, the most common findings in the small bowel were vascular ectasias (6 to 55 percent), ulcerations (3 to 35 percent), and malignancies (3 to 26 percent).10 Other conditions such as small bowel diverticula were present in 2 to 22 percent of patients. No findings were reported in 0 to 57 percent of patients. The diagnostic yield of double-balloon enteroscopy ranged from 41 to 80 percent, with therapeutic success varying from 43 to 76 percent.10 Perforation rates range from 0.3 to 3.6 percent.10,16–18 Studies comparing double-balloon enteroscopy with single-balloon enteroscopy 19 and spiral enteroscopy 20 are lacking.

OTHER STUDIES

Capsule endoscopy and deep enteroscopy have higher overall diagnostic yield compared with small bowel barium studies and CT scans, most likely because vascular ectasias are a common cause. However, advances in CT techniques using multiphasic CT scans with neutral oral contrast media (CT enterography) are more specific for small bowel pathology and may be useful in evaluating the small bowel for tumors and bleeding.21,22 Use of this technology may be limited to referral to an imaging center based on the center's expertise and availability. Nuclear scans and angiography are best suited for overt GI bleeding. The high diagnostic yield, therapeutic capability, and safety of deep enteroscopy have decreased the need for intraoperative enteroscopy and barium studies.

Evaluation

POSITIVE FOBT WITHOUT IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA

The American Gastroenterological Association recommends a stepwise approach to the evaluation of patients who have a positive FOBT without iron deficiency anemia (Figure 6).10 The evaluation begins with colonoscopy. Colonoscopy is preferred because of its high sensitivity for mass lesions and mucosal lesions, and its intervention capabilities with biopsy, polypectomy, and treatment of bleeding lesions. Barium studies have lower sensitivity for mucosal lesions and are generally not recommended. The cost-effectiveness of routinely evaluating the upper GI tract in the setting of a negative colonoscopy is unclear. If colonoscopy is negative, further studies are not required in the asymptomatic patient unless anemia develops.4,8,10,23,24 For patients with upper GI tract symptoms, evaluation with EGD should be performed at the time of colonoscopy. Health care professionals should not attribute a positive FOBT to low-dose aspirin or anticoagulation without further evaluation.4,8,10,24 In one prospective study, 15 of 16 patients receiving anticoagulants with a positive FOBT had significant lesions, and 20 percent of the lesions were malignant.24

IRON DEFICIENCY ANEMIA WITH OR WITHOUT A POSITIVE FOBT

Figure 7 illustrates a recommended approach to the evaluation of patients who have iron deficiency anemia with or without a positive FOBT.25 Until proven otherwise, men and postmenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia are assumed to have GI blood loss. In premenopausal women, menses may be the cause of anemia. However, colonic and upper GI tract lesions, including cancer, have been reported in this group.26 Thus, premenopausal women who have iron deficiency anemia that cannot be explained by heavy menses, or those who have GI symptoms, should be evaluated for a GI cause.4,8,10

All patients should be evaluated for extraintestinal causes such as epistaxis, hematuria, and heavy gynecologic bleeding. Endoscopic evaluation should include EGD and colonoscopy.27 Biopsies should be performed in the duodenum to evaluate for celiac disease. Patients with obscure occult GI bleeding should undergo repeat upper endoscopy and colonoscopy. If these repeat endoscopies are negative, capsule endoscopy should be performed to evaluate the small bowel. If a small bowel lesion is found, the patient may be evaluated with push enteroscopy, deep enteroscopy, or surgery, as clinically indicated. If capsule endoscopy does not reveal a lesion, second-look capsule endoscopy and CT enterography should be considered. In summary, men and postmenopausal women with iron deficiency anemia should undergo progressive evaluation for GI blood loss with colonoscopy, EGD, and capsule endoscopy, as clinically indicated.4,8,10

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms occult gastrointestinal bleeding and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. The search included meta-analyses, clinical trials, and reviews. Other databases searched included the American Gastroenterological Association, American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, Clinical Evidence, Essential Evidence Plus, Evidence-Based Medicine, OvidSP Medline, and UpToDate. Search dates: August 2010 and October 2011.