Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(2):101-108

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Neuropsychologists provide detailed assessments of cognitive and emotional functioning that often cannot be obtained through other diagnostic means. They use standardized assessment tools and integrate the findings with other data to determine whether cognitive decline has occurred, to differentiate neurologic from psychiatric conditions, to identify neurocognitive etiologies, and to determine the relationship between neurologic factors and difficulties in daily functioning. Family physicians should consider referring patients when there are questions about diagnostic decision making or planning of individualized management strategies for patients with mild cognitive impairment, dementia, traumatic brain injury, and other clinical conditions that affect cognitive functioning. Neuropsychological testing can differentiate Alzheimer dementia from nondementia with nearly 90% accuracy. The addition of neuropsychological testing to injury severity variables (e.g., posttraumatic amnesia) increases predicted accuracy in functional outcomes. A neuropsychological evaluation can be helpful in addressing concerns about functional capacities (e.g., ability to drive or live independently) and in determining a patient's capacity to make decisions about health care or finances. Most patients who underwent neuropsychological evaluation and their significant others reported that they found the evaluation helpful in understanding and coping with cognitive problems.

Family physicians are often the first health care professionals to evaluate patients with memory loss and cognitive dysfunction. Although many patients can be readily diagnosed and treated, some present significant challenges. A neuropsychological consultation can help characterize cognitive deficits, clarify diagnoses, and develop optimal management plans for patients with cognitive issues.1 Common goals of neuropsychological evaluations are provided in Table 1.2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Neuropsychological evaluation can identify the onset and type of mild cognitive impairment and dementia so that early intervention can occur. | B | 15, 16, 20, 22, 23 |

| Neuropsychological evaluation can be useful in predicting the degree of driving risk in persons with dementia. | B | 25 |

| Neuropsychological evaluation can be useful in determining decision-making capacity in persons with cognitive impairment. | C | 26 |

| Neuropsychological evaluation can identify cognitive deficits, predict functional outcomes, and monitor patient recovery after traumatic brain injury. | B | 20, 31–38 |

| Goal | Examples |

|---|---|

| Characterize cognitive and behavioral function | Establish cognitive baseline before or after illness, injury, or treatment |

| Evaluate the impact of a medical issue on cognitive, behavioral, or emotional function | |

| Identify cognitive strengths and weaknesses to predict ability to perform daily living activities | |

| Identify subtle cognitive deficits | |

| Prioritize differential diagnoses | Assess for psychological contributions to symptom presentations (e.g., depression, somatoform features) |

| Differentiate “worried well” patients from those with cognitive impairment | |

| Establish, confirm, or differentiate between diagnoses that affect cognition | |

| Evaluate for dementia and differentiate between potential etiologies | |

| Plan and monitor treatment | Help determine candidacy for neurosurgical procedures (e.g., deep brain stimulation, epilepsy surgery, ventricular shunting) |

| Identify cognitive strengths and weaknesses to develop appropriate compensatory strategies and accommodations | |

| Monitor cognitive changes associated with disease progression, recovery, or treatment | |

| Provide prognostic information and treatment recommendations for patients with cognitive disturbances | |

| Address legal, functional, or other issues | Determine whether cognitive deficits may interfere with ability to drive, return to work, or live independently |

| Diagnose or confirm neurodevelopmental disabilities in young adults who are pursuing school or community support | |

| Evaluate the veracity and degree of cognitive and psychiatric symptoms for disability, litigation, and criminal proceedings | |

| Objectively document cognitive disturbances for capacity/competency determinations |

Clinical neuropsychologists are doctoral-level psychologists who have fellowship training in assessment and intervention principles that are based on the scientific study of human behavior as it relates to normal and abnormal brain functioning.1 Neuropsychologists use validated puzzle-based materials, oral questions, and written tests to objectively assess multiple cognitive and emotional functions (Table 2). The tests are typically standardized using large normative samples of healthy age-matched individuals, allowing the examiner to determine the degree to which performance deviates from expected ranges. The results of neuropsychological testing are integrated with other sources of information to provide a comprehensive assessment of a person's cognitive, behavioral, and emotional functioning as a basis for clinical decisions (Table 3).2

| Domain | Tests |

|---|---|

| Academic achievement | Wide Range Achievement Test |

| Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement | |

| Adaptive/functional living | Independent Living Scales |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Attention and working memory | Digit span |

| Letter-number sequencing | |

| Emotional functioning/personality | Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory |

| Personality Assessment Inventory | |

| Executive functioning | Stroop task |

| Trail Making Test | |

| Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | |

| Intelligence | Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence |

| Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale | |

| Memory | California Verbal Learning Test |

| Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test | |

| Wechsler Memory Scale | |

| Mental processing speed | Digit Symbol-Coding |

| Symbol Search | |

| Premorbid estimation | National Adult Reading Test |

| Test of Premorbid Functioning | |

| Psychomotor functioning | Grip strength test |

| Grooved Pegboard Test | |

| Validity | Test of Memory Malingering |

| Word Memory Test | |

| Verbal functions | Boston Naming Test |

| Controlled Oral Word Association Test | |

| Visuospatial functions | Block design test |

| Rey Complex Figure Test and Recognition Trial | |

| Multidomain test batteries | Neuropsychological Assessment Battery |

| Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status |

| Examination of records |

| Family medical, neurologic, and psychiatric history |

| Laboratory, neuroimaging, and previous neuropsychological results (when available) |

| Medical, neurologic, and psychiatric history |

| Medication and substance use history |

| Reason for referral |

| Clinical interview with patient and collateral informant |

| Developmental factors that may affect current condition |

| Emotional, personality, and background factors that may warrant clinical attention |

| Impact of symptoms on daily living |

| Observation of neurobehavioral signs |

| Onset and course of symptoms |

| Neuropsychological testing |

| Administer standardized tests |

| Determine if data patterns reflect specific brain-behavior relations/lesion location |

| Examine degree of cognitive strength and dysfunction |

| Integrate test findings with patient background information |

| Score performance and convert to statistically standardized scores |

| Feedback |

| Answer patient and family questions about cognitive and behavioral functioning |

| Communicate findings, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plan with referring clinician |

| Discuss compensatory strategies with patient |

| Discuss treatment recommendations with patient |

| Provide results, diagnostic impression, and prognosis to patient |

Neuropsychological tests are different in purpose and scope from cognitive screening tests such as the Mini-Mental State Examination3 (Table 4). Screening tests usually take five to 10 minutes to complete and are designed to screen for general cognitive impairment that may warrant a more comprehensive workup. Although screening tests can indicate problems in general cognitive functioning, they have poor ability to assess for deficits in specific cognitive domains. This has been highlighted by research showing that screening test items weakly correlate with scores in the same cognitive domains on neuropsychological testing (correlations range from 0.04 to 0.46).4 Neuropsychological testing typically requires several hours to complete because it comprehensively examines multiple cognitive domains to provide a detailed assessment of the nature and severity of cognitive impairments. This information can contribute significantly when determining primary and secondary diagnoses and planning an individualized rehabilitation/treatment plan.3

| Mini-Mental State Examination |

| No longer freely available; to order: https://www.parinc.com/products/pkey/237 Common cutoff score suggestive of possible cognitive impairment: < 24 |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| Freely available at: http://www.mocatest.org/ Common cutoff score suggestive of possible cognitive impairment: < 26 |

| Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination |

| Freely available at: https://www.slu.edu/medicine/internal-medicine/geriatric-medicine/aging-successfully/assessment-tools/mental-status-exam.php |

| Common cutoff score suggestive of possible cognitive impairment: < 26 (< 24 if less than 12 years of education) |

Neuropsychological evaluations are often complementary to neuroimaging and electrophysiologic procedures.5 Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging evaluate structural integrity within the central nervous system to identify atrophy and lesions. Electroencephalography detects electrical activity of the brain, which is commonly used to assess for epileptic activity. Positron emission tomography identifies cerebral glucose metabolism to determine whether brain activity is reduced in specific regions. However, these procedures have limited diagnostic sensitivity for some neurologic conditions and cannot assess the functional output of the brain. Neuropsychological testing provides an objective assessment of the cognitive, behavioral, and emotional manifestations from cerebral injury or disease.

Because of the unique data that neuropsychological testing provides, physicians have increasingly utilized neuropsychological services.5 In satisfaction surveys, more than 80% of primary care physicians reported that referral questions were satisfactorily answered, and approximately 90% agreed with the diagnostic impressions and treatment recommendations.6 Overall, they found the consulting report useful, and they indicated they would continue to refer patients for neuropsychological evaluations. Commonly referred clinical conditions and primary care referral questions are listed in Table 5.6,7

| Most frequently referred clinical conditions |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| Brain tumor |

| Dementia |

| Neurodevelopmental disorders |

| Seizure disorder |

| Stroke |

| Traumatic brain injury |

| Other medical or neurologic condition |

| Common primary care referral questions/expectations |

| Document functional limitations (e.g., driving, independent living) |

| Establish baseline cognitive functioning |

| Establish or confirm diagnosis |

| Examine competency or other issues that have legal complications |

| Provide second opinion |

| Provide treatment recommendations |

Evidence for Neuropsychological Evaluations

Commonly used neuropsychological test batteries are highly reliable, with reliability coefficients often at or above 0.90 for cognitive index scores.8 Neuropsychological validity studies indicate that tests perform as anticipated in clinical situations. For example, patients with right temporal lobectomies perform below the normative mean on visual memory tests, whereas those with left temporal lobectomies perform below the normative mean on verbal memory tests.8 Patients with right parietal lobe lesions perform poorly on visuospatial constructional tests; those with left-hemisphere lesions perform poorly on expressive verbal ability tests; and those with frontal lobe lesions perform poorly on executive functioning tests.9,10 Empiric evidence for the use of neuropsychological evaluations in persons with dementia, mild cognitive impairment, traumatic brain injury (TBI), and other clinical conditions is summarized below.

DEMENTIA AND MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT

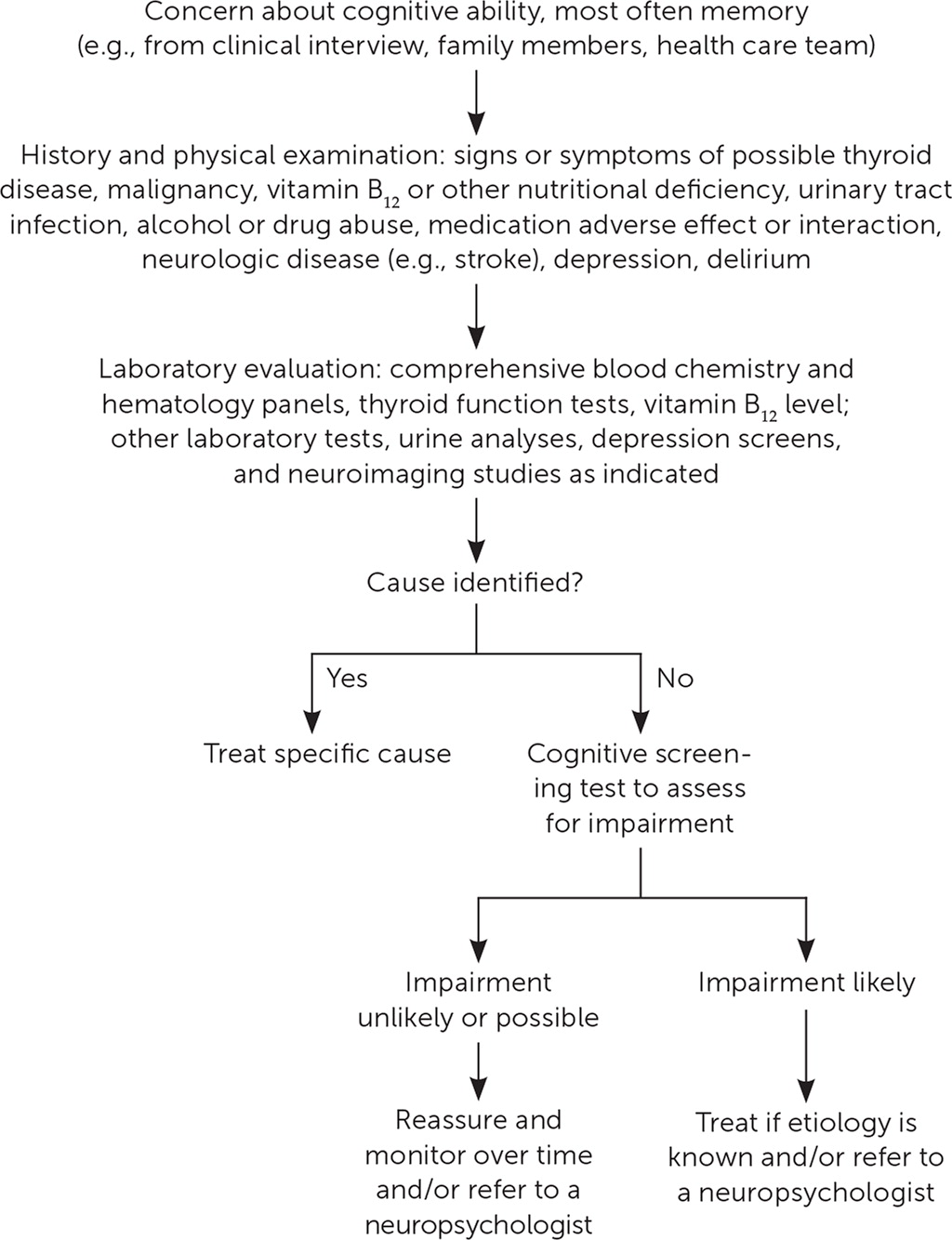

Guidelines from several organizations stress the importance of neuropsychological assessment in the diagnosis and management of dementia. The National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association Workgroup recommends that neuropsychological testing be conducted when the clinical history and mental status examination do not yield confident diagnoses.11 The European Federation of Neurologic Societies–European Neurologic Society states that cognitive assessment has a key role in the diagnosis and management of dementia.12 The International Statistical Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders, 10th rev., and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., state that neuropsychological testing is the preferred method for examining and documenting cognitive dysfunction.13,14 Figure 1 shows an approach to evaluating and managing patients with suspected dementia2; an alternative algorithm that includes the neuropsychological evaluation is available in a recent American Family Physician article (https://www.aafp.org/afp/2018/0315/p398.html#afp20180315p398-f1).

Neuropsychological testing can differentiate Alzheimer dementia from nondementia with nearly 90% accuracy,15 with even higher rates when demographic factors are incorporated with test data (area under the curve = 0.98).16 Neuropsychological evaluations improve diagnostic accuracy even when diagnoses are informed by imaging results and evaluation by subspecialists.17,18 Additionally, studies have shown that neuropsychological testing can differentiate dementia from psychiatric conditions with accuracy rates near 90%.19

Although Alzheimer disease is the most common cause of dementia in adults 60 years and older, dementia is often the result of other disease processes (e.g., Lewy body disease, cerebrovascular disease). Understanding the cause of a patient's dementia can guide family physicians in prescription decisions (e.g., whether to start an acetylcholinesterase inhibitor) and expectations about future symptoms and treatment needs.20 Neuropsychological testing can be a useful tool in this regard, with studies demonstrating strong accuracy in discriminating between different types of dementia.21,22 Neuropsychological testing can also distinguish mild cognitive impairment from normal functioning; sensitivity and specificity rates are approximately 75% and 80%, respectively, when well-established diagnostic criteria are used.15,23 Serial assessments can be useful for patients with mild cognitive impairment or in cases where the etiology of cognitive decline is unclear. A 12-month follow-up is often used to determine whether patterns of cognitive decline are consistent with a suspected etiology, identifying conversion of mild cognitive impairment to dementia, or to monitor the rate of cognitive change over time.5

Neuropsychological assessments are helpful in tracking changes that may affect daily functioning as cognitive impairment and dementia progress.5 Approximately 40% to 50% of the variance in functional decline (i.e., ability to perform personal care activities) is accounted for by cognitive decline.24 In at least 50% of cases, neuropsychological testing can indicate when a patient needs assistance with daily activities.24 Among the challenging situations in which neuropsychological evaluation can be helpful are assessing driving safety and determining health care decision-making capacity. Reduced visuospatial abilities moderately predict on-road driving performance.25 The American Bar Association and American Psychological Association concluded that neuropsychological assessment provides objective information to improve the reliability of capacity determinations.26

TRAUMATIC BRAIN INJURY

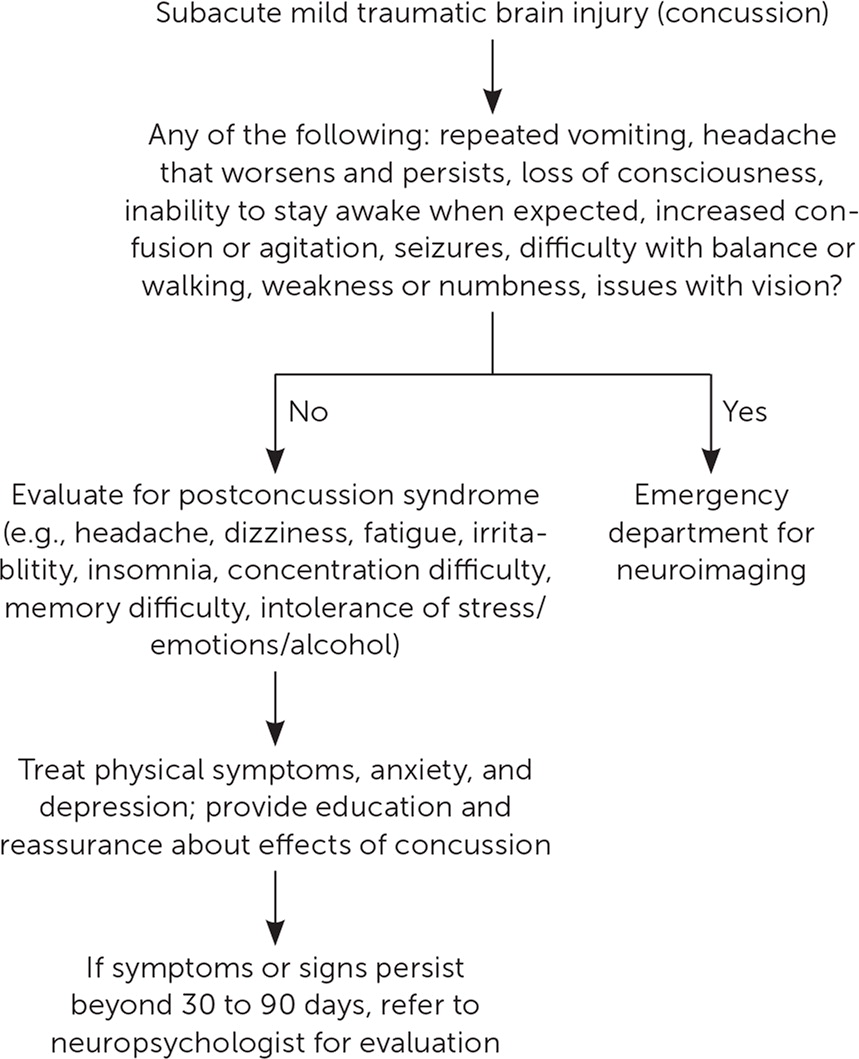

Neuropsychologists are often involved in post–acute TBI management to help determine and predict patient-specific cognitive, emotional, and adaptive functioning27 (Figure 22,28–30). The addition of neuropsychological testing to injury severity variables (e.g., posttraumatic amnesia) increases predicted accuracy in functional outcomes.31 In moderate to severe TBI, neuropsychological status can predict functional independence, return to work, disability utilization, responsiveness to cognitive rehabilitation, and academic achievement.20,32–38

In patients with mild TBI (concussion), in whom long-term cognitive deficits are less likely, a neuropsychological evaluation can identify psychological and other noncognitive factors that may masquerade as cognitive dysfunction and, therefore, can guide appropriate treatment recommendations.28 The Concussion in Sport Group described neuropsychological assessments as a cornerstone of concussion management, and a recent international consensus statement indicated that neuropsychological testing contributes significant information in the evaluation of mild TBI.39 Guidelines recommend that patients who report cognitive symptoms beyond 30 to 90 days after mild TBI be referred for neuropsychological assessment.28,29

Neuropsychologists routinely use performance validity tests in cases where legal issues may be confounding recovery after TBI. These tests assess the validity of a patient's reported symptoms.40 These tests appear more challenging than they actually are; even patients with severe cognitive impairment can perform with near-perfect accuracy. When using cutoff scores and clinical decision rules for multiple tests, accuracy rates are greater than 90%, indicating that results beyond cutoff scores are likely invalid.41 Given their expertise with typical and atypical sequelae of TBI and empiric methods for detecting invalid presentations, neuropsychologists are often involved in evaluating exaggeration or malingering of cognitive and emotional symptoms in TBI cases.

OTHER CLINICAL CONDITIONS THAT CAN AFFECT COGNITIVE FUNCTIONING

The American Academy of Neurology has endorsed the use of neuropsychological evaluation in the assessment and treatment of a variety of conditions, including cerebrovascular disease/stroke, Parkinson disease, human immunodeficiency virus encephalopathy, multiple sclerosis, epilepsy, neurotoxic exposure, and chronic pain.42 Research also demonstrates that neuropsychological evaluations can detect cognitive changes caused by psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder20,43; identify cognitive changes that may emerge before motor abnormalities in the early stage of Huntington disease44; and measure cognitive changes after surgery in patients with brain tumors.45 Neuropsychological evaluations can also detect cognitive issues in patients with developmental disabilities, illnesses, and central nervous system abnormalities.27

Referring for a Neuropsychological Consultation

Referrals for neuropsychological consultation are commonly made by family physicians, neurologists, psychiatrists, and other primary care clinicians. Assessments are typically covered by health insurance if psychological, neurologic, or medical issues are suspected that could affect cognitive or neurobehavioral functioning and if referrals are related to making clinical diagnoses or developing treatment plans. Table 6 shows common indications and exclusions for insurance coverage of neuropsychological evaluations.46

| Indications for probable coverage |

| To determine functional abilities or impairments to establish a treatment plan |

| To determine if adverse effects of therapeutic substances could impair cognition |

| To determine if a patient can participate in health care decision making or independent living |

| To diagnose cognitive or functional deficits based on an inability to develop expected skills |

| To differentiate between psychogenic and neurologic syndromes (e.g., dementia vs. depression) |

| To distinguish between possible disease processes |

| To distinguish cognitive or neurobehavioral abnormalities from normal aging |

| To establish a neurologic or systemic condition known to affect CNS functioning |

| To establish rehabilitation or management strategies for patients with neuropsychiatric disorders |

| To establish the most effective plan of care |

| To establish the presence of cognitive or neurobehavioral abnormalities |

| To monitor progression, recovery, or response to treatment in patients with CNS disorders |

| To provide presurgical cognitive evaluation to determine the safety of the surgical procedure |

| To quantify cognitive or behavioral deficits related to CNS impairment |

| Indications for probable exclusion |

| Active substance abuse that could cause inaccurate test results |

| Adjustment issue associated with moving to a skilled nursing facility |

| Cognitive abnormalities are not suspected |

| Desired information can be obtained through a routine clinical interview |

| Patient is not able to meaningfully participate in the evaluation |

| Repeat testing is not required for medical decision making |

| Self-administered testing or tests used solely for screening |

| Standardized test batteries are not individualized to the patient's symptoms or referral question |

| Test results are not expected to affect medical management |

| Tests administered for educational or vocational purposes that do not establish medical management |

Although availability can sometimes be limited, particularly in rural settings, a listing of neuropsychologists certified by the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology is available at https://theaacn.org/directory. To reduce patient stress and optimize outcomes, physicians should briefly discuss with patients the reason for the referral, the anticipated benefit of the assessment, and the general testing format. Some patients might initially be apprehensive, but surveys show that more than 90% of patients rated their experience as positive or neutral.47 Roughly 80% of patients and their significant others reported that they found the evaluation helpful in understanding and coping with cognitive problems; more than 90% reported being satisfied with the evaluation; and approximately 90% indicated that they would refer others.48 A brief pamphlet for patients who are being referred for testing is available at http://www.div40.org/pdf/NeuropscyhBroch2.pdf.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Michels, et al.2

Data Sources: PubMed, PsychInfo, National Guideline Clearinghouse, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force were the primary sources for the article. Key words included neuropsychological, neuropsychology, cognitive, cognition, dementia, mild cognitive impairment, brain injury, and concussion. Search dates: July 26, 2017, to October 12, 2018.

Editor's Note: Dr. Walling is an Associate Medical Editor for AFP.