Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(2):84-90

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency in which normal traction on the fetal head does not lead to delivery of the shoulders. This can cause neonatal brachial plexus injuries, hypoxia, and maternal trauma, including damage to the bladder, anal sphincter, and rectum, and postpartum hemorrhage. Although fetal macrosomia, prior shoulder dystocia, and preexisting or gestational diabetes mellitus increases the risk of shoulder dystocia, most cases occur without warning. Labor and delivery teams should always be prepared to recognize and treat this emergency. Training and simulation exercises improve physician and team performance when shoulder dystocia occurs. Unequivocally announcing that dystocia is happening, summoning extra assistance, keeping track of the time from delivery of the head to full delivery of the neonate, and communicating with the patient and health care team are helpful. Calm and thoughtful use of release maneuvers such as knee to chest (McRoberts maneuver), suprapubic pressure, posterior arm or shoulder delivery, and internal rotational maneuvers will almost always result in successful delivery. When these are unsuccessful, additional maneuvers, including intentional clavicular fracture or cephalic replacement, may lead to delivery. Each institution should consider the length of time it will take to prepare the operating room for general inhalational anesthesia and abdominal rescue and practice this during simulation exercises.

Shoulder dystocia is an obstetric emergency in which gentle downward traction of the fetal head does not lead to delivery and additional maneuvers are required to deliver the fetal shoulders.1 Shoulder dystocia is usually attributed to impaction of the anterior shoulder against the maternal symphysis after delivery of the fetal head; less commonly, it is caused by impaction of the posterior shoulder against the sacral promontory.2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct team training simulation drills that include identification to improve performance during actual shoulder dystocia emergencies.18 | B | Longitudinal study of a mandatory shoulder dystocia training program |

| Announce unequivocally that there is a shoulder dystocia when it occurs.18 | B | Longitudinal study of a mandatory shoulder dystocia training program |

| Elevate both knees to the chest (McRoberts maneuver) as the first therapeutic maneuver during shoulder dystocia.10 | B | Retrospective analysis of shoulder dystocia cases |

| Consider posterior arm delivery if McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure are unsuccessful.10,14,21 | C | Clinical guidelines based on consensus, computer modeling, and a retrospective analysis of shoulder dystocia cases |

| Document precisely the head-to-body delivery interval and maneuvers performed after every shoulder dystocia.10 | C | Consensus-based clinical guidelines |

Shoulder dystocia complicates 0.3% to 3% of all vaginal deliveries.3,4 The exact incidence can be difficult to determine because the diagnosis is subjective and there are no agreed upon diagnostic criteria for shoulder dystocia. Objective criteria of a head-to-body delivery interval of 60 seconds or the need for additional delivery maneuvers are proposed based on the incidence of significantly more birth injuries and lower Apgar scores during these deliveries.5

Risk Factors and Prevention

Risk factors for shoulder dystocia include fetal macrosomia (odds ratio = 16.1), prior shoulder dystocia (odds ratio = 8.25), and preexisting or gestational diabetes mellitus (odds ratio = 1.8).6–8 Other risk factors include maternal obesity, excessive maternal weight gain during pregnancy, oxytocin (Pitocin) use, prolonged first or second stage labor, and operative vaginal delivery (forceps or vacuum); however, these are poorly predictive of shoulder dystocia.9 There are no accurate models to predict or prevent shoulder dystocia.10,11

Fetal macrosomia is difficult to accurately predict. At term, fetal sonography has at least a 10% margin of error for diagnosis of macrosomia.11 Although the incidence of shoulder dystocia increases with increasing fetal weight and maternal diabetes, one study of pregnancies complicated by shoulder dystocia found that half of the neonates weighed less than 4,000 g (8 lb, 13 oz) and that only 20% of the patients had diabetes.12 Results from studies evaluating labor induction for suspected macrosomia are inconsistent, and induction is not recommended to prevent shoulder dystocia.13 Given the increased risk of shoulder dystocia with increasing fetal weights, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends consideration of cesarean delivery for a patient who does not have diabetes and is carrying a fetus with an estimated fetal weight of 5,000 g (11 lb). ACOG also recommends consideration of cesarean delivery for a patient who has diabetes and is carrying a fetus with an estimated fetal weight of 4,500 g (9 lb, 15 oz).10

Complications

Shoulder dystocia can cause several maternal and neonatal complications (Table 1).10 The most common maternal complications are postpartum hemorrhage (11%) and obstetric anal sphincter injuries (3.8%).15 The most common neonatal injuries are brachial plexus injuries and clavicular or humeral fractures.16 Transient brachial plexus injuries may occur in up to 20% of deliveries complicated by shoulder dystocia.3 Most resolve without permanent disability, although approximately 10% may result in permanent neurologic injury.17 The head-to-body delivery interval does not predict fetal asphyxia or death.10 However, due to the potential for serious maternal or neonatal harm, a systematic approach to expeditious delivery is necessary.10,15

| Maternal Lacerations of the bladder, urethra, vagina, anal sphincter, or rectum Lateral femoral cutaneous neuropathy Postpartum hemorrhage Symphyseal separation Uterine rupture |

| Neonatal Fetal death Fetal hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy Fracture of the clavicle or humerus Neurologic: brachial plexus injury, diaphragmatic paralysis, facial nerve injuries, Horner syndrome |

Initial Response

Physicians should announce delivery of the fetal head so that an assistant can start a timer. If the fetus fails to deliver using normal traction or if retraction of the fetal head against the perineum (turtle sign) occurs, the physician should announce that there is a shoulder dystocia, and the delivery team should call for additional team members to assist. A longitudinal study of a shoulder dystocia simulation program found a significant reduction in neonatal brachial plexus injuries at discharge (7.6% to 1.3%) when the delivery team performed specified actions during shoulder dystocia deliveries.18 These included an unequivocal announcement of the shoulder dystocia, calling for additional assistance from qualified personnel, and having an assistant announce the time from delivery of the fetal head every 30 seconds.

Physicians should also obtain assistance from a physician qualified to perform cesarean delivery and someone to resuscitate the neonate. Additional helpful actions that have not been studied include communicating with the patient so that she knows when to push, lowering the bed, using a stool for the assistant applying suprapubic pressure, and having someone record events for precise documentation.

Delivery Maneuvers

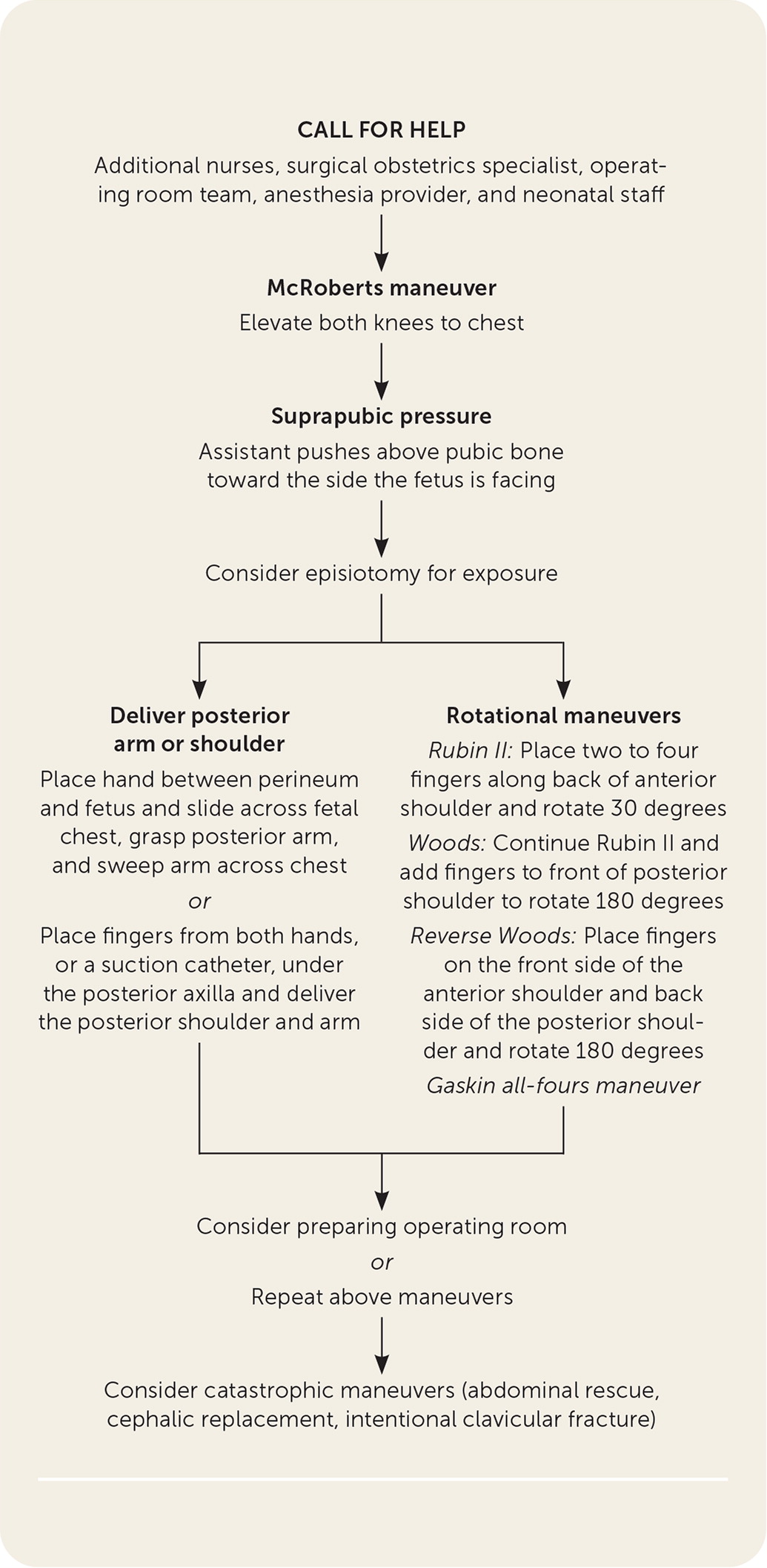

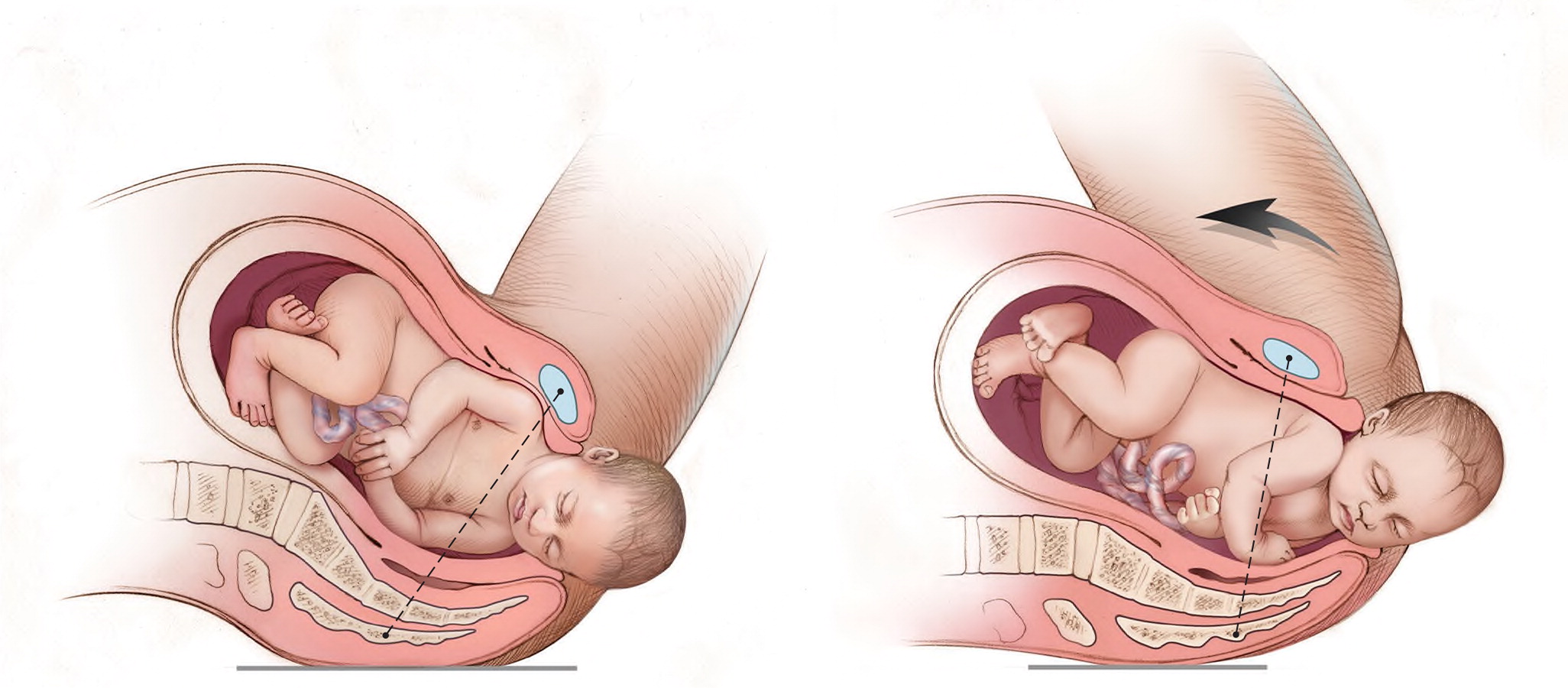

If the fetus does not deliver using gentle traction, release maneuvers can be used in a thoughtful and sequential manner to deliver the impacted shoulder (Figure 1). Aggressive lateral or downward traction on the fetal head and neck should be avoided because it can injure the brachial plexus.4 There are no randomized trials comparing the various maneuvers used to release an impacted shoulder 10 (Table 210,18,19). ACOG, the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and the Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics program recommend using the McRoberts maneuver first, followed by suprapubic pressure if necessary.10,14,19 The McRoberts maneuver, performed by flexing the hips and bringing both knees toward the chest, rotates the symphysis pubis cephalad and further opens the pelvic outlet (Figure 2). This is a simple and proven method to manage shoulder dystocia, with a success rate of up to 42% as the sole maneuver.10,15

| Initial maneuvers* McRoberts Suprapubic pressure Delivery of the posterior arm Menticoglou posterior shoulder delivery Posterior axillary sling traction |

| Secondary maneuvers* Rubin II rotational Woods corkscrew rotational Reverse Woods corkscrew rotational Gaskin all-fours |

| Catastrophic maneuvers Abdominal rescue under general anesthesia Cephalic replacement (Zavanelli) Intentional clavicular fracture |

If delivery does not occur, firm, steady suprapubic pressure should be performed concurrently with the McRoberts maneuver. An assistant should apply firm downward or oblique pressure just above the symphysis pubis toward the side the infant is facing. This decreases the distance between the infant's shoulders (bisacromial distance), potentially assisting anterior shoulder dislodgement (Figure 3). Fundal pressure increases the risk of uterine rupture.20

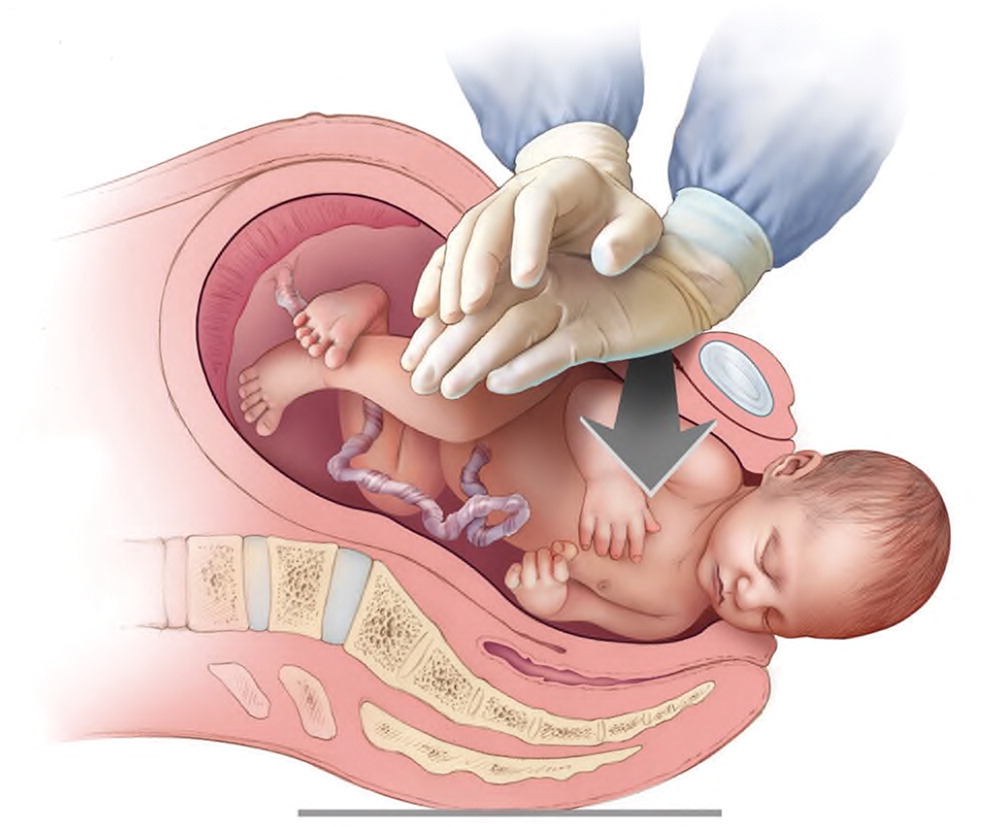

If the McRoberts maneuver and suprapubic pressure are unsuccessful, delivery of the posterior arm should be considered10,14,21 (Figure 4). A retrospective review revealed that the combination of the McRoberts maneuver, suprapubic pressure, and posterior arm delivery resulted in successful delivery within four minutes in 95% of cases.21 Computer modeling suggests that delivery of the posterior arm results in the least amount of brachial plexus stretch compared with other maneuvers.22 Delivery of the posterior arm requires patience and communication to keep the patient calm. Training with a birth simulator will likely improve operator confidence and performance of this procedure.

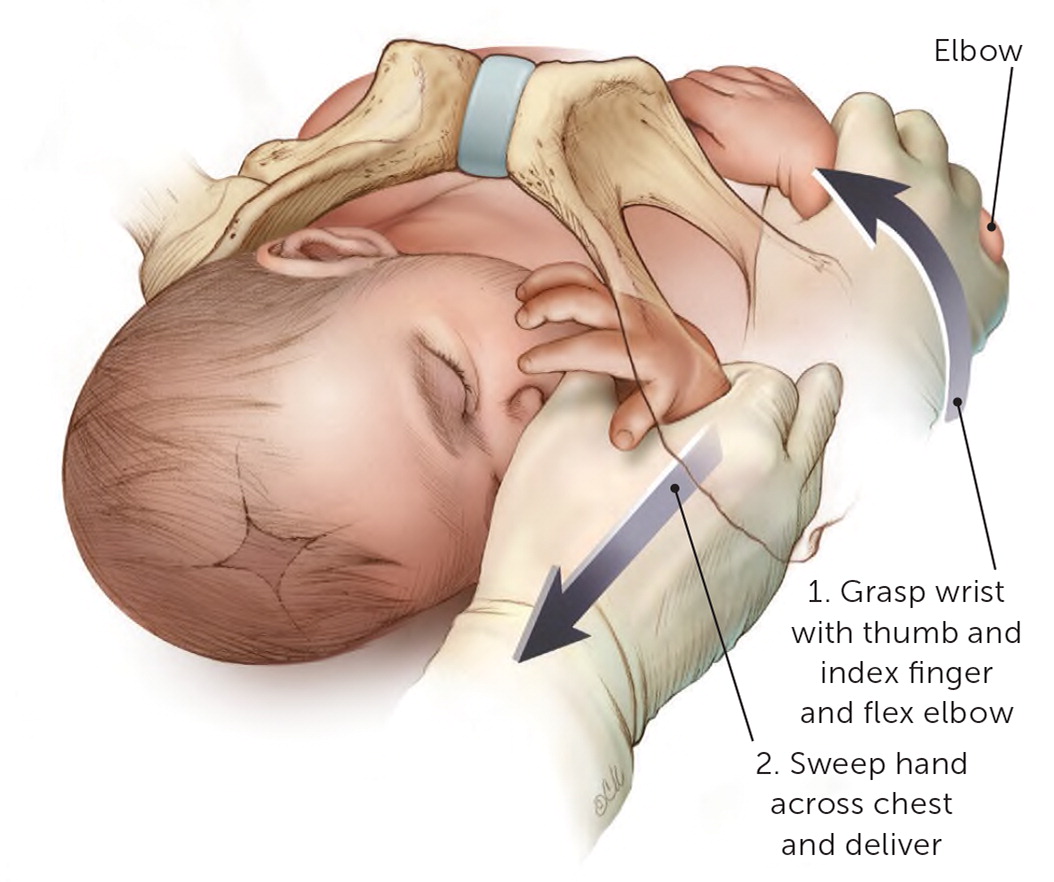

An episiotomy may help depending on the size of the physician's hands and ability to enter the posterior vagina, but it is not mandatory for this or any release maneuver.23 The physician should apply lubricant, compress all five fingers from the appropriate hand into a “duck-bill” shape, and gently maneuver the hand into the posterior vagina, under the baby (see a video of a posterior arm release). The physician should then slide the hand along the fetal chest, not the back, up to the fetal hip, or until the posterior hand is identified. Grasping the wrist by forming an OK sign with the physician's thumb and index finger (Figure 4), he or she should flex the fetal elbow and slide the arm along the fetal chest to deliver from the posterior vagina. Using the operator's fifth finger as a fulcrum by placing it along the fetal elbow may help.

Posterior Arm Release

If the posterior arm is tight against the vaginal sidewall and cannot be delivered, other methods of delivering the posterior shoulder can be used. The Menticoglou maneuver involves placing one finger from each hand under the posterior axilla and applying gentle traction along the curve of the pelvis to deliver the posterior shoulder.24 After the shoulder delivers, it should be easier to deliver the entire posterior arm. The posterior axilla sling traction maneuver uses a suction catheter or urinary catheter placed under the posterior shoulder axilla to apply downward traction to deliver the posterior shoulder.25 Alternatively, the physician can use the sling to rotate the posterior shoulder 180 degrees to anterior, similar to the Woods maneuver. A description and video of this technique is available.

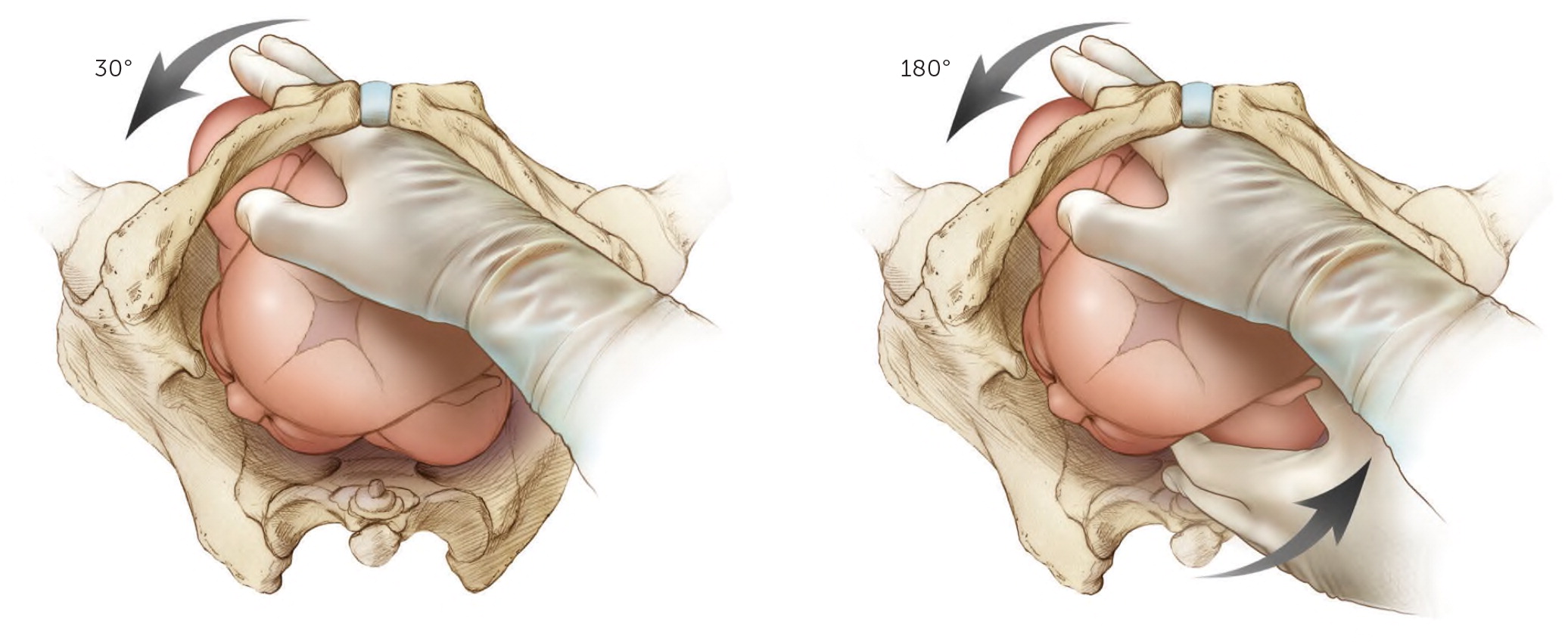

Additional maneuvers include rotational methods (e.g., Rubin II, the Woods or reverse Woods [corkscrew] maneuvers) and rolling the patient to her hands and knees (Gaskin all-fours maneuver). To perform the Rubin II maneuver, the physician places two fingers into the vagina to push the scapula of the anterior fetal shoulder toward the fetal face to attempt to rotate the fetus 30 degrees (Figure 5; see a video of the Rubin II maneuver).

Rubin II Maneuver

The Woods maneuver combines the hand placement for the Rubin II maneuver with two fingers on the anterior aspect of the posterior fetal shoulder with the intent of rotating the fetus 180 degrees (Figure 5; see a video of the Woods maneuver). For the reverse Woods maneuver, fingers or hands are placed on the front side of the anterior shoulder and back side of the posterior shoulder to rotate the fetus 180 degrees. An episiotomy may be helpful for the Woods maneuvers to be able to gain access with two hands. The Gaskin all-fours maneuver requires the patient to roll onto her hands and knees. This had an 83% success rate as the sole maneuver used in one series.26 This maneuver may be more difficult if the patient is fatigued or has neuraxial anesthesia.

Woods Maneuver

Maneuvers for Catastrophic Shoulder Dystocia

If these maneuvers do not result in delivery, options include performing the maneuvers again (Figure 1) or enlisting assistance from another experienced physician who might try the previously attempted maneuvers again or who can collaborate to attempt less proven maneuvers, such as abdominal rescue, cephalic replacement (Zavanelli maneuver), and intentional clavicular fracture (Table 3).10,27,28 Each institution should consider the length of time it will take to prepare the operating room for general inhalational anesthesia and abdominal rescue and practice this during simulation exercises.

| Abdominal rescue Perform a hysterotomy incision and then manipulate the fetus to dislodge the shoulders, allowing vaginal delivery.27 |

| Cephalic replacement (Zavanelli maneuver) Rotate the fetal head to a direct occiput anterior position, flexing the neck so the chin presses against the perineum, then push the head gently into the vagina.28 Apply continuous pressure to hold the head in place while another physician performs a cesarean delivery to extract the baby abdominally. Relaxing the uterus with oral or intravenous nitroglycerin or inhalational anesthetics will likely make this procedure more successful, although this is unproven. |

| Intentional clavicular fracture Pull the clavicles outward to fracture one or both, collapsing the shoulders inward and allowing delivery. However, this can be difficult to perform because of the strength of the clavicles, and it may damage underlying vasculature. Blunt manipulation is recommended; avoid the use of scissors or other sharp instruments.10 |

Documentation

Precise documentation is extremely important after a shoulder dystocia to inform the clinical team of the delivery events, including the head-to-body delivery interval and maneuvers used. ACOG has provided a checklist for documenting the occurrence of shoulder dystocia.29

This article updates a previous article by Baxley and Gobbo.30

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms shoulder dystocia, shoulder, brachial plexus, and abnormal labor. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched Ovid, Clinical Key, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: September 5, 2019, and April 13, 2020.