Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(7):420-426

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

For many patients, pregnancy is a highly anticipated and exciting phase of life, but it can also be anxiety provoking. Family physicians can resolve some of this anxiety and promote maternal and fetal health by making specific recommendations at prenatal visits. A daily prenatal vitamin with at least 400 mcg of folic acid and 30 mg of elemental iron should be recommended to promote neurologic and musculoskeletal fetal development. Weight gain in pregnancy should be guided by preconception body mass index. People who are underweight should gain 28 to 40 lb, those who have a normal weight should gain 25 to 35 lb, and those who are overweight or obese should gain 15 to 25 lb or 11 to 20 lb, respectively. A well-balanced diet including omega-3 fatty acids should be encouraged. Unpasteurized foods should be avoided during pregnancy because of the risk of listeriosis. Caffeine intake should be limited to 200 mg per day (about two small cups of coffee), and artificial sweeteners should be avoided. Pregnant patients should be encouraged to engage in regular cardiovascular activity for at least 150 minutes per week. Bed rest is not recommended. Sex can be continued throughout an uncomplicated pregnancy. Avoidance of alcohol and marijuana is recommended. The effects of hair dye or hair straightening products on fetal development or neonatal outcomes are unclear.

In 2016, prenatal care was initiated in the first trimester in more than 75% of pregnancies,1 providing a multitude of opportunities for family physicians to counsel these patients on the basics of a healthy pregnancy. During prenatal visits, physicians can dispel many myths about pregnancy. This article will discuss physical activity, provide recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy, review components of a well-balanced diet, discuss supplement and medication use, and dispel myths related to topics that have traditionally been taboo: sex and the use of marijuana and alcohol during pregnancy. Communicating this information in an individualized manner will promote maternal and fetal health.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Weight gain during pregnancy should be individualized based on prepregnancy body mass index.2–6 | C | Systematic review, cohort study, and guidelines showing that early weight gain and maternal obesity are associated with higher infant mortality |

| Unpasteurized foods should not be consumed during pregnancy.7,8 | C | Practice recommendations and analysis showing poor neonatal outcomes in patients with listeriosis |

| A prenatal vitamin with folic acid, vitamin D, calcium, and iron should be recommended for pregnant patients.1,3,4,9 | A | Meta-analyses and systematic reviews showing decreased fetal neural tube defects and promotion of musculoskeletal development |

| Instead of routinely being given a fish oil supplement, pregnant patients should be encouraged to consume two or three servings per week of fish that contains low levels of mercury.3,11 | B | Randomized controlled trials showing that high fish consumption decreases preterm birth, observational studies showing increased neurodevelopment in children, and expert opinion/usual practice |

| Pregnant patients should be encouraged to engage in moderate-intensity exercise for at least 150 minutes per week.15,16,19,20 | B | Systematic review and meta-analyses showing fewer newborn complications and maternal health benefits |

| Alcohol should not be consumed during pregnancy.36,37 | C | Case-control study showing risk of fetal alcohol spectrum disorder and lower birth weight |

| Caffeine intake should be limited to 200 mg per day during pregnancy.41,42 | A | Meta-analyses showing increased early pregnancy loss with high doses of caffeine |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not place patients, even those at high risk, on activity restriction to prevent preterm birth. | Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine |

| Do not routinely recommend activity restriction or bed rest during pregnancy for any indication. | American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists |

Weight Gain and Diet

The National Academy of Medicine recommends that weight gain during pregnancy be based on preconception body mass index (Table 1).2 Patients should be counseled that pregnancy does not require doubling caloric intake.2 Weight goals should be individualized according to the baseline fitness level, prepregnancy weight, and other metabolic considerations. A safe recommendation is 350 to 450 calories per day above the previous intake3 (e.g., two slices of bread with half an avocado, ¾ cup of Greek yogurt or 1 cup of blueberries with two hard-boiled eggs). These recommendations optimize birth weight and minimize adverse pregnancy outcomes.2,4 Excessive weight gain and preexisting maternal obesity are associated with increased antepartum complications, including fetal death, stillbirth, and neonatal death5,6 (Table 25).

| Prepregnancy body mass index (kg per m2) | Category | Recommended weight gain |

|---|---|---|

| < 18.5 | Underweight | 28 to 40 lb (12.7 to 18.1 kg) |

| 18.5 to 24.9 | Normal weight | 25 to 35 lb (11.3 to 15.9 kg) |

| 25.0 to 29.9 | Overweight | 15 to 25 lb (6.8 to 11.3 kg) |

| ≥ 30 | Obese | 11 to 20 lb (5.0 to 9.1 kg) |

| Risk | Absolute risk per 10,000 pregnancies (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal BMI = 20 kg per m2 | Maternal BMI = 25 kg per m2 | Maternal BMI = 30 kg per m2 | |

| Fetal death | 76 | 82 (76 to 88) | 102 (93 to 112) |

| Stillbirth | 40 | 48 (46 to 51) | 59 (55 to 63) |

| Perinatal death | 66 | 73 (67 to 81) | 86 (76 to 98) |

| Neonatal death | 20 | 21 (19 to 23) | 24 (22 to 27) |

| Infant death | 33 | 37 (34 to 39) | 43 (40 to 47) |

When advising pregnant patients about their diet, physicians should counsel about foods to limit or avoid. Foods such as soft cheeses made from unpasteurized milk, deli meats, sprouts, melons not eaten immediately after cutting, and raw or smoked fish can be contaminated with Listeria monocytogenes. The risk of listeriosis is 18 times higher in patients who are pregnant compared with the general population.7 Other unpasteurized foods such as kefir, kombucha, and kimchi are less well studied. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that all unpasteurized foods be avoided during pregnancy to prevent listeriosis.8 The mortality rate of fetal listeriosis is 25% to 35%, depending on the gestational age at the time of infection.7

Vitamins and Supplements

A well-balanced diet rich in vitamin D, folic acid, iron, calcium, omega-3 fatty acids, and other micronutrients should be encouraged for pregnant patients (Table 33,9–14). Prenatal vitamins are recommended because they provide folic acid, iron, calcium, and vitamin D. Ideally, they should be started before conception and should contain at least 400 mcg of folic acid,2,3 30 mg of elemental iron,2,3 200 to 300 mg of calcium,4 and 400 IU of vitamin D.4 Because of the role that vitamin D plays in bone development, the daily recommended intake for patients of childbearing age is 600 IU.9 Vitamin D can be obtained from fortified cereals, pasta, breads, cow's milk, cheese, and yogurt.9 Salmon and eggs are also excellent sources.9 Vitamin D can be synthesized in the skin when exposed to sunlight.9

Calcium is an important part of the prenatal diet. The recommended daily intake is 1,000 mg for people 19 years and older and 1,300 mg for those 14 to 18 years of age.9 Calcium can be obtained from milk and other dairy sources, and it is present in lower concentrations in dark green leafy vegetables.

Pregnant patients should be encouraged to consume two or three servings per week of fish with high levels of omega-3 fatty acids, including docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which is important for normal eye and brain health in newborns.3,10 Supplementation has been shown to prolong gestation and increase infant size, but natural sources are better than supplements.11 Fish with high mercury content (e.g., swordfish, shark, orange roughy) should be avoided.

Vegetarianism and veganism have increased in popularity over the past several years. Neonatal outcomes in vegetarians or vegans are generally the same as in omnivores, as long as the dietary restrictions are not associated with poverty or limited access to food.12 Supplementation may be required for nutrients that are typically found in animal products, such as vitamins B12 and D.13 All pregnant patients should be encouraged to read the label on their prenatal vitamin to ensure that their daily intake is consistent with guidelines.

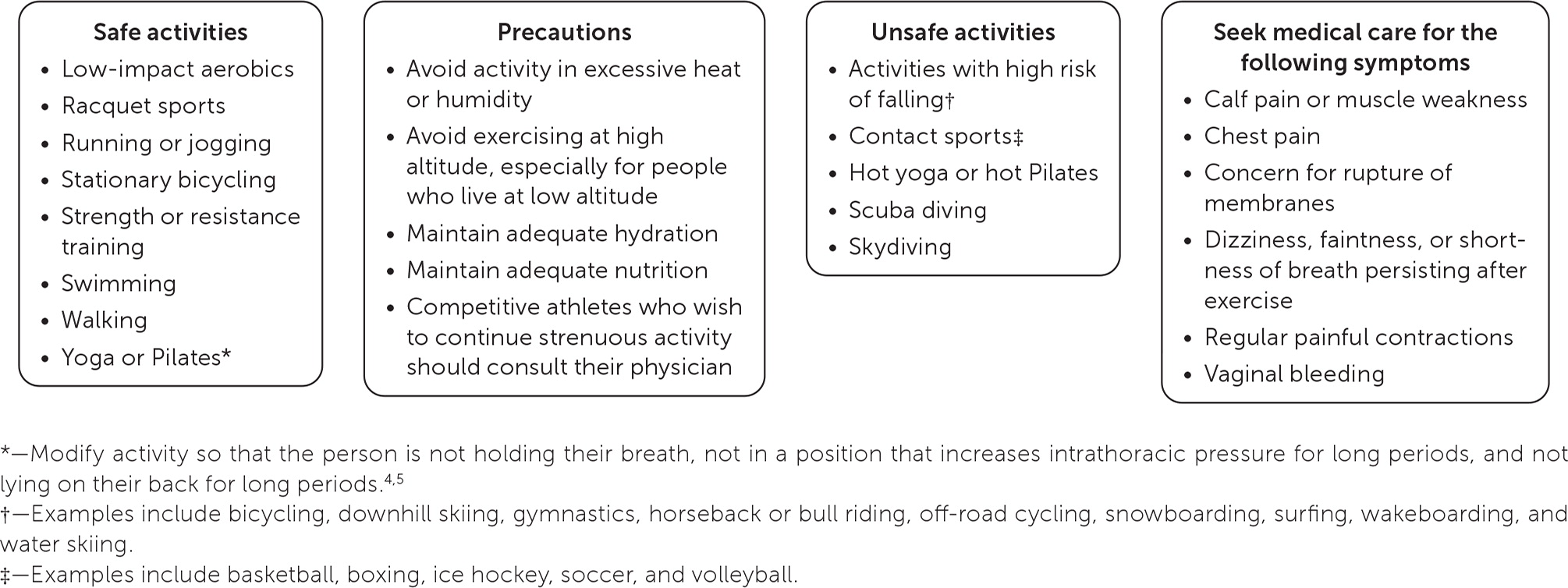

Activity

Patients with uncomplicated pregnancies should be encouraged to engage in physical activity and can continue physically demanding occupations with guidance from their physician.15 They may continue their prepregnancy level of exertion as long as it does not include activities with a higher risk of injury and trauma, such as snowboarding or contact sports3,13 (Figure 14,5,15–18). Exercise recommendations should be individualized during pregnancy and should take into consideration any obstetric complications or preexisting medical conditions3,15 (Table 415,16,19). Patients should be encouraged to engage in moderate aerobic activity most days of the week for at least 20 to 30 minutes at a time,15,19 for a total of at least 150 minutes per week.16 Physical activity should also include resistance training.16 A randomized controlled trial showed that yoga during pregnancy improved maternal well-being during the second and third trimesters.20

| Absolute contraindications | |

|---|---|

| Hemodynamically significant heart disease Incompetent cervix with or without cerclage Intrauterine growth restriction* Multiple gestation at risk of preterm labor Higher-order multiples (triplets, etc.) Monoamniotic-monochorionic twins Persistent or unexplained vaginal bleeding Placenta previa after 26 to 28 weeks' gestation Preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension* Preterm labor Restrictive lung disease Ruptured membranes Severe anemia Uncontrolled chronic medical conditions Hypertension Thyroid disease Type 1 diabetes mellitus | |

| Relative contraindications | |

| Extreme morbid obesity† Extreme underweight (body mass index < 12 kg per m2) and malnutrition Heavy smoker History of extremely sedentary lifestyle History of preterm labor and birth Maternal cardiac arrhythmia Mild or moderate respiratory or cardiovascular disease Multiple gestation after 28th week Musculoskeletal conditions‡ Symptomatic anemia Uncontrolled medical conditions Hyperthyroidism Seizure disorders |

Heart rate may be blunted during pregnancy and should not be used to assess exercise intensity. Rather, perceived exertion should be used and individualized.15 Regular physical activity during pregnancy can sustain and improve cardiovascular fitness; improve mood; decrease postpartum recovery time; and decrease the risks of gestational diabetes mellitus, excessive weight gain, operative delivery, cesarean delivery, and preeclampsia.15 To prevent thermal injury and maintain euglycemia, pregnant patients should be encouraged to exercise in a temperature-controlled environment, wear loose clothing, maintain hydration, and consume adequate calories before and after exercise.15,16 Clinical guidelines from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health recommend weight limits for occupational lifting based on gestational age (see Figure 2 at https://www.ajog.org/article/S0002-9378(13)00242-1/fulltext).21

Swimming and hot tub use can be recommended during pregnancy, but it is not known whether the chemicals used to treat swimming pools and hot tubs affect a developing fetus. A recent study suggested that people who regularly swam in pools during their pregnancies had infants with smaller head circumferences22; however, there was no significant difference in birth weight. The temperature of the water may have more of an impact on fetal development than the chemical exposure. Studies examining heat exposure via hot tubs during early pregnancy showed an increased risk of neural tube defects, esophageal atresia, and omphalocele.23,24 Repeated exposure may increase the risk of these defects.

Medications

One in four pregnant patients 15 to 44 years of age has taken a prescription medication in the past 30 days.26,27 A prospective cohort study found that nearly all participants used medications during their pregnancies: 95% in the first trimester, and 97% at any time.28 Common indications included allergy symptoms, colds, urinary tract infections, gastrointestinal ailments, respiratory disease, cardiovascular disease, and pain.29 The most common over-the-counter medications taken in the first trimester were ibuprofen, acetaminophen, aspirin, naproxen, pseudoephedrine, and docusate.30 Amoxicillin, progesterone, albuterol, progestins, and estrogens were the most commonly taken prescribed medications.30 Generally, first- and second-generation antihistamines, acetaminophen, histamine H2 blockers, and proton pump inhibitors can be used without fetal risk in any trimester.29 Physicians should review the use and safety of other over-the-counter and prescription medications with pregnant patients.

Medication safety during pregnancy has been reported and labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration since 1979.31 In 2015, the agency ended its A, B, C, D, X classification system and now requires data from human and animal studies to be reported narratively 31,32 (Table 529,31,32). Labeling for over-the-counter medications has not changed.31,32

| FDA Pregnancy Risk Categories, 1979 to 2015 | Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule, 2015 to present* |

|---|---|

| Category A: Well-controlled studies failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus in the first trimester of pregnancy, and there is no evidence of risk in later trimesters Category B: Animal studies failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus, and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant patients Category C: Animal studies demonstrated adverse fetal effects, and there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans; the drug should be given only if potential benefits justify potential fetal risks Category D: There is positive evidence of human fetal risk, but the drug may be acceptable to use if safer drugs are not available or ineffective, or in life-threatening situations despite potential risks Category X: Studies in animals or humans demonstrated fetal abnormalities, and the risks involved in the use of the drug in pregnant patients clearly outweigh potential benefits; these drugs are contraindicated in people who are pregnant or who could become pregnant | Pregnancy (includes labor and delivery) Pregnancy exposure registry Risk summary Clinical considerations Data Lactation Risk summary Clinical considerations Data People with reproductive potential Pregnancy testing Contraception Infertility |

Sex

Patients undergo constant changes during pregnancy, from their hormone levels to their physical appearance. This can translate to changes in their sex lives. Although some report a lack of libido, others may avoid intercourse for fear of hurting the fetus or experiencing physical discomfort.33 A recent cohort study showed that the frequency and timing of sex had no significant effects on maternal or neonatal outcomes.33 In healthy pregnancies, patients should be encouraged to participate in physical intimacy with their partner if they wish to do so.

Alcohol, Marijuana, Caffeine, Artificial Sweeteners, and Hair Treatments

ALCOHOL

Fetal alcohol spectrum disorder is a well-known complication of excessive fetal alcohol exposure.34 Children born to people who regularly consume more than six drinks per day are at increased risk of this disorder.35 Some studies suggest that even low to moderate consumption of alcohol may have negative effects on fetal development, including reduced length, lower birth weight, and more crying during the first few months of life.36,37 Therefore, alcohol use in any amount during pregnancy should be discouraged.

MARIJUANA

The prevalence of marijuana use is increasing as it is legalized in more states.35,38,39 Intractable nausea and vomiting are indications in many states for prescription of medical marijuana.38 However, given the potential harm to the fetus, it is not recommended to treat nausea and vomiting related to pregnancy. Potential harms include low birth weight and increased risk of admission to neonatal intensive care, and heavy use can be associated with preterm labor.38,39 Marijuana use should be avoided during pregnancy.40

CAFFEINE AND ARTIFICIAL SWEETENERS

Many drinks, such as coffee, tea, and sodas, contain caffeine and artificial sweeteners. Consuming excessive amounts of coffee (more than 350 mg of caffeine per day or about 3.5 cups of coffee) during pregnancy is strongly associated with early pregnancy loss, preterm delivery, and low birth weight.41,42 The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that caffeine intake be limited to 200 mg per day (about two small cups of coffee) during pregnancy.3 Artificial sweeteners are associated with infants who are large for gestational age, and they increase the risk of childhood overweight or obesity.43 Infants who are exposed to artificial sweeteners in utero may be at increased risk of metabolic syndrome when they are older.44

HAIR TREATMENTS

The effects of hair dye or hair straightening products on fetal development and neonatal outcomes are unclear. A Brazilian study found an association between maternal and paternal prenatal exposure and the development of acute lymphocytic leukemia and acute myeloblastic leukemia in children younger than two years.45 Additional research is necessary to definitively recommend for or against the routine use of hair treatments during pregnancy.

Data Sources: A PubMed search was conducted using the key phrases activity restriction in pregnancy, diet in pregnancy, beauty products in pregnancy, pregnancy and swimming pools, pregnancy and hair dye, obesity in pregnancy, vitamin D in pregnancy, drugs in pregnancy, veganism in pregnancy, prenatal care in pregnancy, pregnancy and hot tubs, artificial sweeteners in pregnancy, pregnancy and marijuana, alcohol in pregnancy, caffeine in pregnancy, and sexual intercourse in pregnancy. The search included systematic and clinical reviews, meta-analyses, reviews of clinical trials, evidence-based guidelines, clinical practice guidelines, and prescribing package inserts. We also searched the Cochrane database, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Clinical Evidence, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: March 2019 to March 2020.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.