Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(2):179-185

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Sinus node dysfunction, previously known as sick sinus syndrome, describes disorders related to abnormal conduction and propagation of electrical impulses at the sinoatrial node. An abnormal atrial rate may result in the inability to meet physiologic demands, especially during periods of stress or physical activity. Sinus node dysfunction may occur at any age, but is usually more common in older persons. The causes of sinus node dysfunction are intrinsic (e.g., degenerative idiopathic fibrosis, cardiac remodeling) or extrinsic (e.g., medications, metabolic abnormalities) to the sinoatrial node. Many extrinsic causes are reversible. Electrocardiography findings include sinus bradycardia, sinus pauses or arrest, sinoatrial exit block, chronotropic incompetence, or alternating bradycardia and tachycardia (i.e., bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome). Clinical symptoms result from the hypoperfusion of end organs. About 50% of patients present with cerebral hypoperfusion (e.g., syncope, presyncope, lightheadedness, cerebrovascular accident). Other symptoms include palpitations, decreased physical activity tolerance, angina, muscular fatigue, or oliguria. A diagnosis is made by directly correlating symptoms with a bradyarrhythmia and eliminating potentially reversible extrinsic causes. Heart rate monitoring using electrocardiography or ambulatory cardiac event monitoring is performed based on the frequency of symptoms. An exercise stress test should be performed when symptoms are associated with exertion. The patient's inability to reach a heart rate of at least 80% of their predicted maximum (220 beats per minute – age) may indicate chronotropic incompetence, which is present in 50% of patients with sinus node dysfunction. First-line treatment for patients with confirmed sinus node dysfunction is permanent pacemaker placement with atrial-based pacing and limited ventricular pacing when necessary.

Sinus node dysfunction, previously known as sick sinus syndrome, is characterized by abnormal initiation and propagation of electrical impulses from the sinoatrial node (SAN). The resulting abnormalities include bradycardia (less than 50 beats per minute [bpm]), sinus pause (more than three seconds), sinus arrest, and sinoatrial exit blocks, which are sometimes associated with supraventricular tachyarrhythmias in bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome1–4 (Table 15–11). Bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome occurs in approximately 50% of patients with sinus node dysfunction and increases the risk of stroke and death.5,12 Symptoms manifest as end-organ hypoperfusion, including palpitations, decreased physical activity tolerance, easy fatigability, dizziness, and syncope.2,5,6,13 To diagnose sinus node dysfunction, a combination of symptoms and documented electrical abnormalities must be present.5,7

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| A diagnosis of sinus node dysfunction requires direct correlation of observed bradyarrhythmia with symptoms of end-organ hypoperfusion.2,5 | C | Expert opinion and consensus guideline |

| Permanent pacemaker placement with atrial-based pacing is the first-line therapy for symptomatic treatment of sinus node dysfunction.2,5,37,38 | B | Expert opinion, consensus guidelines, and randomized controlled trial with three-year follow-up analysis |

| In patients who decline permanent pacemaker placement, a trial of phosphodiesterase inhibitors may be effective for controlling symptoms associated with sinus node dysfunction.2,35 | C | Consensus guideline and retrospective case-control study |

| Finding | Description |

|---|---|

| Bradycardia | Sinus bradycardia: sinus rhythm with HR < 50 bpm Atrial fibrillation with slow ventricular rate: ventricular rate with HR < 50 bpm Wandering pacemaker: at least three distinct P waves with HR < 50 bpm |

| Bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome | Present in 50% of patients at time of sinus node dysfunction diagnosis; atrial tachyarrhythmias alternating with bradycardia |

| Sinus node arrest | Complete loss of automaticity of the sinus node; prolonged asystole with or without escape rhythm (junctional or idioventricular) |

| Sinoatrial exit block | First-degree: conduction delay between the sinoatrial node and atrial tissue; bradycardia as above Second-degree type 1: single impulse blocked; pause following progressive decrease in the P–P interval* Second-degree type 2: single impulse blocked; distinct pause preceded by generally constant P–P interval* Third-degree: multiple impulses blocked within sinus node; pause followed by a beat originating with atrial depolarization (i.e., preceded by a P wave) |

Epidemiology

Sinus node dysfunction may occur at any age7,14; however, increasing age is the most significant risk factor with the highest disease prevalence in patients 70 to 89 years of age.2,7,8,14 The incidence of sinus node dysfunction is 0.8 per 1,000 person-years and is expected to double by 2060 due to the aging population.15 Conditions associated with advanced age such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, and coronary heart disease are overlapping risk factors and potential causes of sinus node dysfunction.2,15 Brugada syndrome, a rare inherited ion channel disorder that results in ventricular tachyarrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, is also associated with sinus node dysfunction.5,16,17

Etiology

| Intrinsic causes Acute myocardial infarction Cardiomyopathies Congenital ion channel dysfunction (HCN4, SCN5A mutations) Connective tissue diseases Embolization of the sinoatrial node artery Idiopathic degenerative fibrosis Infection (Chagas disease [cardiomyopathy], diphtheria [myocarditis], rheumatic heart disease, typhoid) Infiltrative disease (amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, sarcoidosis) Muscular dystrophy Postsurgical changes or surgical injury to the sinoatrial node Extrinsic causes Diabetes mellitus (risk factor for structural or physiologic changes) Excessive vagal tone (athletic training, during sleep, postmyocardial infarction) Hypertension (risk factor for structural or physiologic changes) Medications: antiarrhythmic drugs (Class I and II); amiodarone, amitriptyline, beta blockers, cimetidine (Tagamet), digoxin, lithium, marijuana, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers; sympatholytic drugs Metabolic abnormalities (hyperkalemia, hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, hypothermia, hypothyroidism, hypoxia) Toxins |

INTRINSIC CAUSES

Intrinsic causes originate from structural or functional changes within the SAN. These changes can occur because of fibrosis, ischemia, cardiac remodeling, infiltrative disease, or ion channel dysfunction. 8,18,19 Degenerative idiopathic fibrosis of the SAN is the most common cause of sinus node dysfunction.4,5,7,8,15 Elastic fiber and fatty and fibrous tissue buildup at the SAN and surrounding myocardial tissue increases with age and may lead to prolonged SAN refractory time and, therefore, a decreased intrinsic heart rate.2,4,8 Ischemic heart disease and embolization of the sinus node artery may cause ischemic necrosis of the node, resulting in sinus node dysfunction.8 Acute myocardial infarction may induce a transient sinus node dysfunction caused by autonomic disturbance and increased vagal tone.2,12 Cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or advanced age can result in structural changes that decrease cardiac tissue voltage transmission and ultimately delay or block the SAN and result in sinus node dysfunction.3,8,14

Another result of this remodeling is the formation of bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome. It is unclear if a supraventricular tachycardia or sinus node dysfunction is the primary disorder in bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome. The etiology is further complicated by current contradictory evidence about the role of supraventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation as a cause of sinus node dysfunction.3 At a minimum, it is clear that these diagnoses are associated even if the causal pathway is unclear.

Infiltrative diseases such as sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, hemochromatosis, and connective tissue diseases can disrupt the cardiac tissue and result in abnormal SAN function.2,5 Similarly, sinus node dysfunction has been associated with cardiomyopathy from infection with Chagas disease, with which the arrhythmia may be permanent.6,8 Rhythm abnormalities associated with myocarditis from infections such as diphtheria and typhoid and immune-mediated disorders such as rheumatic fever may cause sinus node dysfunction temporarily.6,8

About 80% of patients younger than 21 years with sinus node dysfunction have a history of congenital heart malformations (e.g., atrial septal defect, transposition of the great arteries) that required surgical intervention.18,20 Genetic mutations in genes responsible for coding ion channels, such as HCN4 and SCN5A, have also been identified as a cause of intrinsic sinus node dysfunction.18

EXTRINSIC CAUSES

Extrinsic causes are related to external factors causing abnormal conduction at the SAN. These causes include medications, metabolic abnormalities, autonomic imbalances, toxins, and endocrine disorders (Table 22,5–8,18). Extrinsic causes may be reversible, such as electrolyte abnormalities, hypothyroidism, metabolic abnormalities, and certain medications.2,8 Anesthesia (e.g., sympatholytic drugs) has been shown to induce autonomic imbalances that may mimic sinus node dysfunction or may reveal the underlying dysfunction in previously asymptomatic patients.8,21 Other pharmacotherapies known to cause sinus node dysfunction include beta blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, digoxin, lithium, and antiarrhythmics.5,7,8 Toxins such as nicotine and marijuana have also been implicated in sinus node dysfunction.7,8,22

Evaluation

Patients with sinus node dysfunction typically present with end-organ hypoperfusion symptoms from decreased cardiac output caused by the underlying arrhythmia (Table 15–11). The most common symptoms of cerebral hypoperfusion are syncope, presyncope, lightheadedness, and cerebrovascular accidents, with syncope occurring in 50% of patients with sinus node dysfunction.2,5,7,23 Cardiovascular hypoperfusion can present with palpitations, decreased physical activity tolerance, angina, or, less commonly, heart failure. Musculoskeletal hypoperfusion can present with muscle fatigue. Renal hypoperfusion can present as oliguria.2,5,6,13,23 Correlation between symptoms and arrhythmias is considered the diagnostic standard (on electrocardiography [ECG] or other cardiac monitoring).2,5,6

Diagnosis

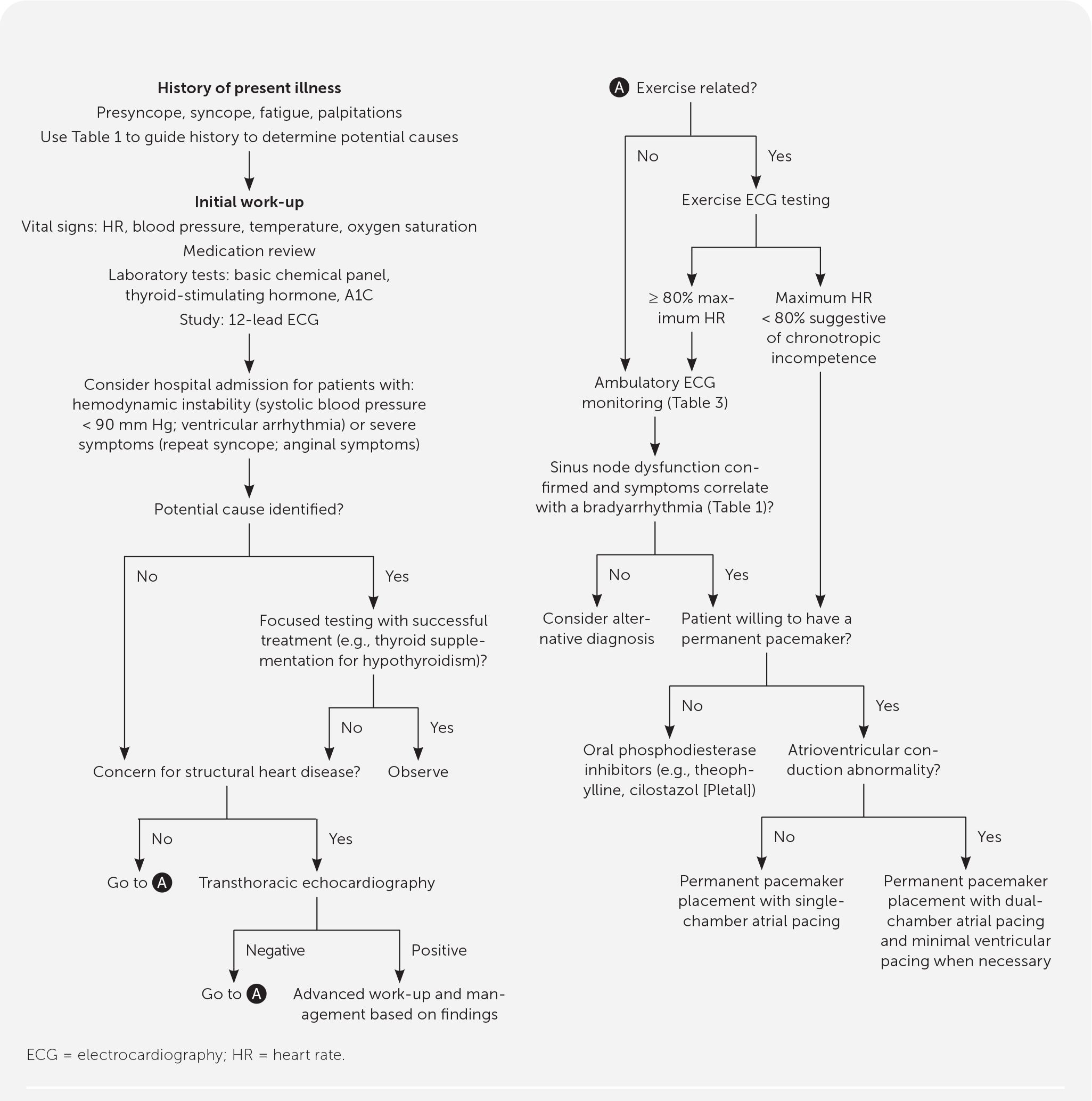

A definitive diagnosis of sinus node dysfunction is established when symptoms are directly associated with cardiac monitoring that demonstrates a bradyarrhythmia2,6 (Table 15–11). The initial assessment should begin with a history and physical examination (Figure 12–4,8,14,17,21,24). Clinicians should focus their history by investigating the intrinsic and extrinsic causes of sinus node dysfunction (Table 22,5–8,18). It should include a medication review to assess for a potential extrinsic cause. Initial diagnostic evaluation should include 12-lead ECG, a basic chemical panel to assess for metabolic abnormalities, and any additional laboratory tests needed to rule out other extrinsic causes that were not excluded by the history or physical examination (i.e., thyroid-stimulating hormone to rule out hypothyroidism or A1C to rule out diabetic atrial myopathy).5,6

Initial evaluation of sinus node dysfunction can be performed in an outpatient setting; patients with hemodynamic instability (i.e., systolic blood pressure less than 90 mm Hg, ventricular arrhythmias) or severe symptoms (i.e., recurrent syncope, anginal symptoms) should be hospitalized because these patients need urgent evaluation and may require temporary transcutaneous pacing for stabilization.2 When a potential extrinsic factor is identified during the workup, further evaluation should focus on confirming the diagnosis followed by a trial of therapy. With successful treatment of the extrinsic factor (e.g., continuous positive airway pressure for confirmed sleep apnea or thyroid supplementation for hypothyroidism) and subsequent resolution of sinus node dysfunction, no further workup is indicated.

Patients with history or physical examination findings for underlying structural defects such as a history of valvular disease, new cardiac murmur, bibasilar crackles, lower extremity edema, or concerning ECG findings (e.g., left bundle branch block, second-degree Mobitz type II block, third-degree atrioventricular block) should have transthoracic echocardiography.2 If the results suggest a specific pathology, further workup and treatment should be initiated based on the suspected etiology. Abnormal results may be because of complications from sinus node dysfunction or an alternative diagnosis, and will require further workup and potential specialty referral for evaluation and treatment.

Chronotropic incompetence is associated with sinus node dysfunction, with 50% of patients diagnosed with sinus node dysfunction also meeting chronotropic incompetence criteria.25,26 It is a separate diagnosis associated with an array of diseases, including sinus node dysfunction. Chronotropic incompetence is defined as the sinus node's inability to mount a heart rate high enough to meet physiologic demands during exertion, resulting in symptoms of central nervous system hypoperfusion similar to those found in sinus node dysfunction.5,25 When symptoms are associated with exertion, the patient should have an exercise ECG test to assess chronotropic incompetence. A diagnosis of chronotropic incompetence is made if the patient is unable to meet 80% of the maximum heart rate (220 bpm – age) during exertion.2,25 It is important to distinguish that chronotropic incompetence is a separate disease process and alone is not enough to diagnose sinus node dysfunction. Sinus node dysfunction and chronotropic incompetence follow the same treatment algorithm (Figure 12–4,8,14,17,21,24 ).

When initial 12-lead ECG is unable to confirm sinus node dysfunction by correlating symptoms with a definitive bradyarrhythmia (Table 15–11), further electrical monitoring is indicated.2,5,9 There are multiple types of ambulatory monitoring available. These devices include continuous monitoring (e.g., Holter monitor, external patch recorder, ambulatory telemetry) and patient- or event-activated devices (e.g., event monitor, external loop recorder, implantable loop recorder). First-line devices include the original Holter monitor or the external patch recorder.8,9,27–32 The external patch recorder is a smaller second-generation monitor that is water-resistant and can be worn for seven to 14 days. The external patch recorder detected more arrhythmias and was better tolerated by patients compared with the Holter monitor.31,33 The frequency of symptoms, the patient's ability to use the device, and the need for continuous vs. intermittent monitoring should be considered when deciding the best form of monitoring for a patient.9 Table 3 lists cardiac monitoring options with associated indications and pros and cons of use.9,27–31 If sinus node dysfunction cannot be definitively established after ambulatory monitoring is completed, further evaluation for an alternative diagnosis and expert consultation should be considered.

| Type of monitor | Description | Indication | Time frame | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holter monitor | External leads that monitor for short time span; data analyzed after return of device | First-line | 24 to 48 hours; can be up to two weeks | Inexpensive, continuous | Analyzed after return of device; symptoms must be present during time of monitoring |

| Event monitor or patient-activated loop recorder | External leads or armband that provides continuous monitoring; patient must activate for data to record (some have automatic recording for arrhythmias); data are transmitted over telephone to monitoring station | Second-line in patients who can activate monitor with onset of symptoms | Two to four weeks | Longer duration of monitoring, real time analysis, smaller than Holter monitor | Must be activated by the patient during symptoms; symptoms must be present during time of monitoring |

| Real time continuous monitoring | External leads that provide continuous monitoring; records and analyzes all data, transmits automatically; data are transmitted over telephone to monitoring station | Second-line in patients unlikely to be able to activate monitor with onset of symptoms | Two to four weeks | Longer duration of monitoring, real time analysis, continuous (not patient activated) | Requires system to continually monitor data; symptoms must be present during time of monitoring |

| External patch recorders | External small leadless patch that provides continuous monitoring; data analyzed after return of device | Alternative to loop recorders | Two to 14 days | Real time analysis, continuous, leadless, smaller size than external loop recorders and therefore more patient friendly | Requires system to continually monitor data; symptoms must be present during time of monitoring |

| Implantable loop recorders | Subcutaneously implanted monitoring device with remote transmission of data | Persistent syncope/presyncope despite extensive previously negative workup | One to two years | Longest duration of monitoring | Increased risk with invasive placement; expensive |

Treatment

Permanent pacemaker placement is the first-line treatment for patients with confirmed sinus node dysfunction,2,5,34–36 accounting for 50% of pacemakers implanted in the United States.5,7,12 Pacemaker therapy has been found to provide symptom relief and improve quality of life, but it is unclear if it provides a mortality benefit.5,36 This treatment includes patients with chronotropic incompetence and patients with pharmacologically induced sinus node dysfunction where continued treatment is clinically necessary. Atrial-based pacing has been established as superior because right ventricular pacing has been associated with an increased risk of arrhythmias and decreased cardiac function.2,37,38 A well-powered randomized controlled trial demonstrated no difference in mortality, stroke, heart failure, or atrial fibrillation hospitalizations when comparing single-chamber atrial pacing with dual-chamber atrial pacing.21 However, over five years of follow-up, 3% to 35% of patients will transition from a single-chamber atrial device to a dual-chamber device with minimized ventricular pacing.2,6 To minimize the risk of these additional procedures, patients with evidence of atrioventricular nodal or bundle branch conduction dysfunction should be considered for initial dual-chamber device placement.2 It is common in the United States for patients to receive a dual-chamber device with right atrial pacing unless otherwise indicated. Overall, permanent pacemaker placement is relatively safe, with complications estimated at less than 1% to 6%. Most common complications include lead dislodgment (5.7% in left ventricular leads), hematomas (3.5%), venous thrombus/obstruction (2%), infections (1%), and pneumothorax (1%).34

Medication control of sinus node dysfunction is a secondary option for patients who decline permanent pacemaker placement. Phosphodiesterase inhibitors (e.g., theophylline, cilostazol [Pletal]) have a positive chronotropic effect, resulting in symptom control for patients with sinus node dysfunction. However, the long-term impact of medication control on disease progression and mortality is unclear.2,35 Other pharmaceuticals (e.g., atropine, dopamine, epinephrine, glucagon) used in advanced cardiac life support protocols for acutely unstable bradycardic patients are effective for short-term control of unstable patients but are not appropriate for long-term management of sinus node dysfunction because of significant adverse effect profiles.2,35

The role of oral anticoagulation in patients with sinus node dysfunction is unclear. There is limited evidence to support its use in patients with sinus node dysfunction who do not have another indication for anticoagulation therapy.2,37,39 Anticoagulation is currently not routinely recommended for the treatment of sinus node dysfunction.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Semelka, et al.,5 and by Adán and Crown.7

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Key words included sinus node dysfunction, sick sinus syndrome, causes, bradyarrhythmia, permanent pacemaker indications, chronotropic incompetence, loop recorders, ambulator cardiac monitoring. The search included practice guidelines, randomized controlled trials, a retrospective case control study, and review articles. Search dates: December 2019 to October 2020.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are those of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University, the U.S. Air Force Medical Department, the Air Force at large, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the Army at large, or the U.S. Department of Defense.