Clinical Practice Culture: Moving from Surviving to Thriving

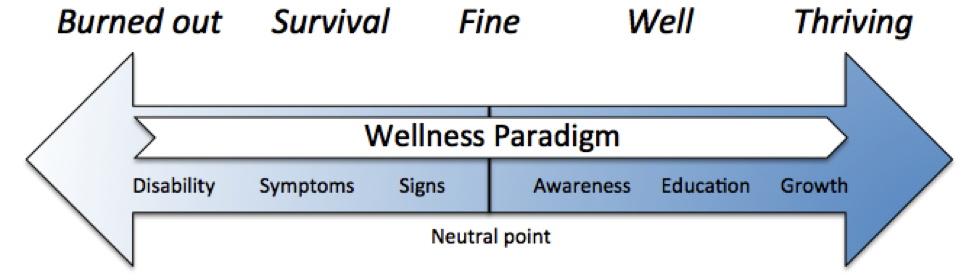

In 2014, the Mayo Clinic released an updated study revealing that 63 percent of family physicians qualify as “burned out.” But does that mean the other 37 percent of family physicians are thriving? It’s more likely that many are in “survival mode,” according to Mark H. Greenawald, MD, FAAFP, a family physician who chairs the physician well-being committee at Carilion Clinic in Roanoke, Virginia. Family physicians operate along a wellness continuum that ranges from burned out to thriving, he explains.

Existing in survival mode or a “fine” practice culture affects the physician, says Greenawald, but it also affects everyone he or she comes into contact with: staff, patients, family, and friends.

“You’ll never provide five out of five care if you’re functioning as a one or two out of five,” Greenawald notes. “The math doesn’t add up.”

In spite of the odds, he says, it is possible to move from burned out or just surviving to thriving. Purposefully creating a clinical practice culture that supports your well-being is one way to progress along the wellness continuum. In many cases, this may involve reshaping an established practice culture because the discomfort and effort of changing are less burdensome than staying the same.

“Find out where you are on the continuum and what it would take to get to a better place than you are right now,” Greenawald suggests. “It has to be very deliberate. There are many forces in health care that will tend to drag us back to being in burnout or survival mode.”

Greenawald has coined an approach to shaping an optimal practice culture that identifies six components for consideration, using the acronym STARRS:

- Service

- Teamwork

- Attitude

- Reflection

- Renewal

- Self-care

These components make up the operational and relational aspects of your work. Operational aspects include functions and tasks, such as practice structure, flow of care, productivity, efficiency, and optimization of the electronic health record (EHR). The relational side involves interactions, such as how you conduct yourself, how you regard (or disregard) your colleagues and staff, and how you treat your patients.

A Thriving Practice Culture

In this three-part series, Dr. Greenawald offers some practical tips for how to get started creating a thriving practice culture.

Greenawald suggests the following tactics as starting points to design a practice culture that supports your well-being:

- Articulate the vision. Be deliberate about asking and answering specific, meaningful questions, such as:

1. “What is the vision for this practice?”

2. “What does it mean to provide excellent service to patients and to colleagues?”

3. “How do we know if we’re achieving the vision?”

- Conduct “State of the YOUnion” assessments. Developed by Greenawald, these assessments are a way to evaluate yourself, your team, and your interactions as a manager/leader on an interpersonal level. In addition, the information gathered in the assessments can help you identify specific ways to improve your culture and your relationships with colleagues and staff. Better interpersonal relationships in the practice will help you advance along the wellness continuum.

- Have clinical huddles. Huddles typically focus on operational effectiveness, but it’s also important for the care team to check in with each other personally. Professional or personal issues that are causing a team member to be distracted or less effective can affect everyone in the practice, including patients.

- Get a PeerRX. As you shape your practice culture, identify another physician who can be an accountability partner. Regularly check in with one another to offer support, advice, and a listening ear.

According to Greenawald, taking deliberate steps to create a clinical practice culture in which you can thrive can result in improved patient care, a better quality of life, and physician, practice, and specialty sustainability.

“As health care providers believing in health, it should be not only our duty, but part of our DNA to try to create that better place,” Greenawald says. “It’s the right thing to do, not just for us, but ethically for our patients.”

Resources

- Creating Strong Team Culture (American Medical Association STEPS Forward)

- State of the YOUnion Assessments

Written by AAFP editorial staff.

Mark H. Greenawald, MD, FAAFP, is Vice Chair for Academic Affairs and Professional Development, Carilion Clinic Department of Family and Community Medicine, and an associate professor of family and community medicine at the Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia. He is on faculty at Carilion Clinic’s family medicine residency program, chairs the Carilion Clinic physician well-being committee, and serves as the director for the American Academy of Family Physician’s (AAFP’s) Chief Resident Leadership Development Program.

References

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general U.S. working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600-1613.