It really can be a do-it-yourself project – and you probably have the basic tools already.

Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10(2):37-40

Is your practice choking on paper? This article can help you get rid of some of it. Are you always hunting for one document or another – from the most recent version of your office policies to a needed patient handout? This article can help you put them in one place and find them from anywhere you are in your practice. Want to be able to fill out and print clear, legible hospital orders? This article can make it a snap. Developing your own intranet can simplify life for you and your staff.

KEY POINTS

An office intranet is easy to construct, and it can both increase efficiency and improve information sharing within your practice.

With an intranet, your staff can have one-click access to a variety of documents.

The key is to start small. You can even build an intranet with your word processing program.

What’s an intranet?

For practical purposes, think of an intranet as a private collection of computer files that are accessible through a Web browser such as Netscape or Internet Explorer. Typically, these files are stored on a local area network (LAN), and they’re accessible to users logged into the LAN but not accessible over the Internet. If your practice has a LAN, you’re well on your way to having an intranet.

The computer files making up your practice intranet could be whatever you want. While Web pages (i.e., HTML documents) are the most common, word processing documents, spreadsheets, Adobe Acrobat (PDF) documents, etc., can all be part of the intranet. Making these documents into a practice intranet offers you several advantages:

You can store one copy of each document while making it instantly available to any computer on the network.

You and your staff can use the familiar Web browser interface to open documents from a variety of programs.

When you update a file such as your office policy manual, that update becomes instantly available to all users.

You can “hyperlink” from one document to one or more others, making it easy for users to move between related documents.

You can easily create organized menus of hyperlinks, making the documents into an easy-to-use collection.

You can include links to sites on the World Wide Web. Thus, a list of links to your favorite patient handouts can intermingle ones you have developed yourself with ones that are available online – all organized by subject or any other way that makes sense to you.

You can have easy access to your own consent forms, as well as to forms that another facility might need (e.g., admission orders), printed in one click.

You can have a virtual address book of tertiary-care-center physicians and resources without having to update the data.

But I’m not a Web developer!

Creating an intranet may sound harder than it is. In fact, you can probably build a perfectly adequate intranet for a small work-group just using your word processing program. For example, Corel WordPerfect and Microsoft Word allow you to insert hyperlinks into files and to save any file as an HTML Web page, so you could do the whole job with one of them. How easy can it get? Microsoft Excel and PowerPoint also let you save files as HTML files. And, of course, you can get fancier and use programs designed specifically for creating Web sites and editing HTML files, such as Microsoft FrontPage (www.microsoft.com/frontpage) and CoffeeCup HTML Editor (www.coffeecup.com/editor). I’ve used these programs to go beyond the basics and create customizable forms with drop-down menus, etc. – but frills like that are definitely optional.

When the Internet took off in 1995 with capable Web browsers that could hyperlink to other documents and sites, I had already started to develop my own intranet of documents my staff and I use every day. I was too busy to do much work on the intranet until 1998, when the electronic medical record (EMR) program we use, Practice Partner Patient Records by Physician Micro Systems, Inc., created a Web browser within the program. This aspect of Patient Records has revolutionized our office operations. But you don’t need to have such an EMR system to develop your own intranet. All you need is a reasonable level of comfort using a computer.

Start small

In the following, I am going to assume that you have several computers in your office, all linked by a LAN of some kind. If the network also gives all of the networked computers high-speed access to the Internet, so much the better, but that is not required. Here’s one way to approach developing your intranet:

First, determine where your intranet files are going to reside. If you don’t have a system such as our Practice Partner Patient Records that takes care of this, you’ll need to create a folder somewhere on your network, where it is accessible to all the linked computers. Call the folder Intranet.

Second, start with some small part of what you want to include in your intranet. For the moment, I’ll assume that you’re going to start with a main menu and a few links to useful patient handouts that you already have stored on a computer somewhere. (That’s what we did.) Create a folder inside your new intranet folder called Handouts and copy into it the files for the patient handouts you want to include. These can be the original word processing files, or you can use the “Save as …” command in your word processor to create HTML versions. (You can later create other folders inside the intranet folder for office policies, procedures, various forms, etc.)

Third, create a menu to link the pieces of your document collection together. Here’s how you would do it using Microsoft Word. Create a file that looks something like the one shown below, listing the titles of the handouts in your new folder. Then choose the “Save as …” command in the File menu. In the resulting dialogue box, enter Menu.htm as the file name, select “HTML Document” from the pop-up “Save file as type” menu, and save it in the new folder named Intranet.

Use the mouse to select the first title, click the “Insert hyperlink” button in the toolbar and follow the directions to locate the handout file. Click OK, and you have your first hyperlink. Repeat for the other handouts. Close the file when you’re done. (To change the menu later, you can open the Menu.htm file directly in Word and add links, text, graphics, tables, etc.)

Finally, start your Web browser and select “Open file …” from the File menu. Navigate to your new Menu.htm file and click OK. Try the links. If you saved the handouts as HTML files, you should be able to view them with the Web browser; if not, the Web browser should start Word (or whatever program you created the handouts in) and open the handout files. (Note: Some browsers may actually download temporary copies of any non-HTML documents to your desktop before calling on the appropriate program to open them. Those copies will be deleted automatically when you quit the browser.)

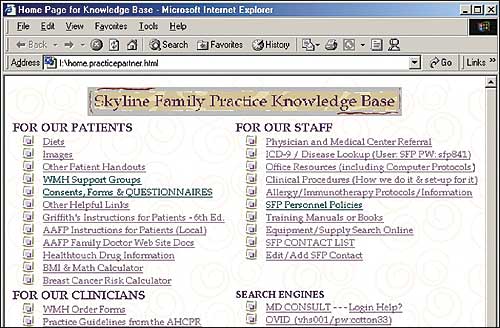

You have the beginnings of your intranet. Now you can add the page to your Favorites or Bookmarks or even choose it as your new home page (located under the Preferences menu in your Browser). And you can build from there. To give you a sense of where we are in our practice, the main menu of our current intranet is shown above.

Even though this is reasonably easy, and even though your imagination may be filling with possible uses, be careful not to get too ambitious too soon. Taking on too much is a good way to ensure that the project drags on or dies on the vine. Break it down into manageable pieces and celebrate completion of each part of your project. Done right, a project such as this can be the spark that rejuvenates physicians and staff alike. If your patients see you printing handouts from your own intranet, or if you allow them to do so while in the office, the intranet will become a word-of-mouth marketing feature! The benefits go on and on.

Resources to include

What kind of useful documents can you have in your intranet collection? Here are some examples you might want to consider:

Patient education materials. Here you can intermingle documents you create, ones you have licensed from others (such as the handouts from Clinical Reference Systems that we got as part of our EMR system) and Web links – assuming that you’re connected to the Internet. You can link to sites such as the AAFP’s familydoctor.org (www.familydoctor.org), MD Consult (www.mdconsult.com), Medscape (www.medscape.com) and various special-focus sites such as those maintained by the American Diabetes Association and the American Heart Association.

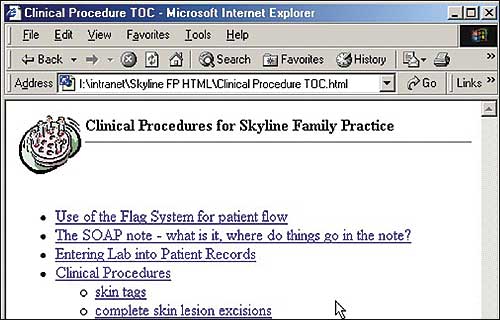

Staff resources. Manuals for operating software and equipment now come in PDF format, so why not link to them? We have also created our own detailed descriptions of setup for clinical procedures, even illustrating them with photographs taken with a digital camera (see page 40). But this only scratches the surface of what you can provide for your staff. Here are some other ideas:

Staff office policies in one up-to-date version that’s always available.

Training materials for new staff (for instance, we used PowerPoint to create training slide programs that are now linked to the intranet menu).

Contact management. There are several possibilities here. For instance, Web sites of tertiary care centers always have search pages for locating physicians and other resources; why not let them keep the information on physicians and other resources up-to-date by simply linking to their search pages? That way, you won’t have to do it. You might also be able to link to your own contact database, if you have one. For instance, Microsoft Access 2000 can create an HTML “data access page” that links the user to an Access database.

RESOURCES

HTML 4 for Dummies, Quick Reference. 2nd Edition. Ray DS, Ray EJ. Foster City, Calif: IDG Books; 2000.

Web Database Development – Step by Step. Buyens J. Redmond, Wash: Microsoft Press; 2000.

Mastering HTML 4. Ray DS, Ray EJ. San Francisco: Sybex Publishers; 1999.

Using Microsoft FrontPage 2000. Randall N, Jones D. Indianapolis: Que – A Division of Macmillan Computer Publishing; 1999.

Compliance documentation. Keep all of your laboratory (CLIA) and OSHA procedures on your intranet. Your CLIA/COLA inspector will love it!

Physician resources. Through your intranet menu, you can link to Web sites you consult often and references that change often, such as the AAFP current immunizations page (https://www.aafp.org/online/en/home/clinical/immunizationres.html).

We have created pages that mimic our hospital’s order sheet, with drop-down menus for filling in the blanks, so that we can produce well-organized, legibly printed orders in a few minutes.

And more! Other possibilities are limited only by your imagination. We even have a link to the State Bureau of Insurance complaint form for Virginia. When a patient complains about an insurance company, we print out the complaint form and give it to the patient. What about vaccine information and consent forms? Even the Vaccine Information Statements (www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/VIS/default.htm) and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System form (VAERS form; www.vaers.org/pdf/vaers_form.pdf) are in PDF format. Why not link them in? You can also include consent forms for sigmoidoscopy and other procedures, and print them out already dated. And think of all the other Internet resources out there, from BMI calculators to health risk assessment programs. Give them a home on your intranet.

In summary, you can start now to become more efficient. You can do a lot with tools you probably already have, and if you’re interested in learning more, cyberspace is the limit. All you really need is your imagination!

TIPS FOR CREATING YOUR INTRANET

These suggestions may make the job easier:

If your intranet contains lots of documents, create two levels of menus. For instance, instead of including links to 20 handouts on your main menu, you can have one “Handouts” link that takes the user to a second menu file that lists all 20. Just don’t add too many layers of menus. The main menu should be no more than three clicks from any document.

Organize your directory (folder) structure to reflect your linkages and name them for what they contain. For instance, a folder called Forms would have in it the forms menu file and a subfolder containing the files for various forms.

Use HTML files unless there’s a good reason to keep a document in another format. While your intranet documents can be word processing files, spreadsheets, Adobe Acrobat files, etc., users must have the proper software to open each kind. Any Web browser can open HTML files, which makes HTML the quickest and easiest format to use.

Intermingle links to documents on the Web with links to your own documents on any menu.

Dig into the Help files of programs such as Microsoft Word and Corel WordPerfect to uncover surprisingly helpful tools for creating and editing HTML pages.