One office cut down on missed appointments by putting its problem patients on probation.

Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(2):65-66

Doctors everywhere struggle with patients who frequently miss appointments. This is a major problem for medical practices in urban areas, especially those catering primarily to underserved communities. At our academic practice in Milwaukee, habitual no-shows finally reached a point where we had to take action. The creative scheduling solution we came up with can easily be re-created in other offices.

Frustration for all

The average rate of no-shows nationally in 2000 was 5.5 percent, according to the Medical Group Management Association. Sixty-three percent of groups tracked missed appointments and cancellations, but only 46 percent had policies addressing this problem.

As these offices try to maintain productivity and financial stability, they often resort to double booking patients. The staff then struggles to balance patient flow and flaring tempers. The physician has two patients every 15 minutes. Patients who arrive on time are treated like an imposition. And everyone's praying that someone will not show. The potential for staff frustration and patient dissatisfaction is enormous.

At the same time, most physicians in underserved communities want to accommodate patient needs. Most clinics also understand that the decision to discharge patients could limit their access to health care. Therefore, termination is usually reserved for the most egregious patient behaviors.

Some practices have adopted “first-come, first-served” models, which lead to long waits. Others are incorporating advanced access models. Although these have worked well for some offices, they are not a solution for many of our problem patients who require advanced notice for scheduling and must arrange for transportation at least 24 hours ahead.

How to break the habit

Between 2000 and 2002, the average no-show rate for our academic practice was 30 percent. We intuitively believed that a disproportionate number of missed appointments were being caused by a small group of patients. In 2002, our practice had 12,100 arrived visits and 4,438 no-shows. No-shows were defined as intended appointments that were not canceled or rescheduled at least two hours before the designated time. Each no-show patient had between one and 18 missed appointments. This accounted for more than 1,300 clinic hours. These no-show visits were caused by 2,138 people. Fifty-three percent (1,128) of the patients who no-showed did so only once.

As theorized, a habitual no-show population existed. We defined this group as those who missed four or more visits in 2002. Twelve percent (254) of the no-show patients had saddled us with 35 percent (1,536) of the no-show visits.

A visceral response would have been to terminate this group. But once we identified the 254 people, we realized that most were well-known to the physicians. Almost all of our chronic no-shows in turn had chronic conditions that required close monitoring. Because our clinic is located in a health professional shortage area, termination would have put these people's health at risk. The habitual no-show patients had an average of 7.3 arrived visits compared with the overall clinic average of 2.3 visits. They constituted 7 percent of patients but generated 15 percent of the arrived visits.

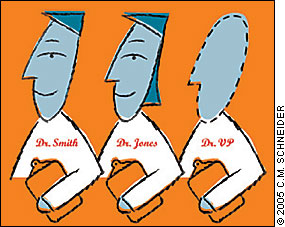

In order to prevent mass terminations, we developed an innovative scheduling alternative. We added a new doctor – first name “Virtual,” last name “Physician” – into our scheduling database. When our habitual no-shows scheduled an appointment, we place them on Dr. Virtual Physician's (or Dr. VP, as we have come to call it) wide-open calendar. The primary care physician's schedule is not affected by the chronic no-show's appointment. If the no-show patient does appear for the appointment, they are placed in the queue behind the on-time patient.

We contacted our habitual no-show patients, both with letters and by phone, to explain that they were on a six-month alternative scheduling probation. They were told that if they were able to make their appointments, they would return to the regular schedule. If not, they could be terminated from our practice. Most, fully aware of how many appointments they had missed, were understanding of the new arrangement.

Now showing: no-shows

During this probationary period, patients can only see their primary care physician. Exceptions are made for acute care needs. When an appointment is made, it is with the understanding that the patient will have to wait until the regularly scheduled patient has been seen. This reinforces that prompt arrivals will be seen in a timely manner. If and when Dr. VP's patients show up, they are simply rescheduled immediately with their regular primary care physician. This allows for continuity of care and assures that colleagues won't have to handle their partners' add-ons. Usually the primary care physicians do not mind seeing their habitual no-show patients because they know them well and agree that termination would not be in the patient's best interest. In our office, the likelihood that a habitual no-show patient will actually arrive is only 46 percent, averaging only 3.6 additional patients per day.

Our virtual physician increases scheduling capacity by double-booking the system – not the individual. It removes habitual no-shows from the physician schedules, reducing wasted time slots. It increases provider productivity by supplying appointment slots for patients who are more likely to arrive. It shortens the time between appointment request and schedule availability. This also helps decrease the no-show rate by allowing patients with urgent needs to be seen today.

Dr. VP has decreased our no-show rate by 20 percent and contributed to a 30 percent increase in visits among faculty physicians. This increased productivity has allowed our residency practice to continue its mission of helping our underserved urban community. Our alternative scheduling system has benefited patients and physicians alike. Virtual physicians can be an inexpensive option toward managing the habitual no-show patients in your medical practice, too.