Even subtle bias can affect our patients, but talking about it can help.

Fam Pract Manag. 2016;23(4):44

Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

It was 1997, and I had recently immigrated to the United States from Argentina to complete a fellowship in adolescent medicine and a master's degree in public health. I was seeing a doctor for the first time at my university for a recently developed rash. Exhausted, I just wanted a prescription. The doctor had taken some initial notes and then got called out of the exam room. As I sat there waiting, I noticed my chart lying open on the counter, and one sentence caught my eye: Patient states that she is a "physician."

It took the air out of me. Did this physician doubt my words? Why? I left the exam room that day feeling confused and hurt.

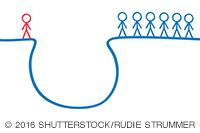

Years later, I came across the Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. It showed that although physicians are supposed to protect, enable, and heal, we are among the perpetrators of bias, discrimination, and stereotyping. I began thinking about how to provide sensitive care by opening up this crucial conversation, starting with some of the most vulnerable patients: adolescent minorities.

Caring for teens often involves positive youth development,1 which includes coaching teens on being able to conquer all the basic developmental tasks by the end of their young adult years. Identity development is one of those crucial tasks, and it turns out that teens belonging to minority communities have an additional task that is quite complex: figuring out what ethnic group they belong to or identify with, and doing this in the context of a family that most likely is at a different point in the process.

When caring for teen patients, I usually initiate a conversation about their identity. I say, “I know that growing up can be rough as you try to figure out who you are on so many levels – culturally, vocationally, politically, sexually, religiously, and so on.” Then, I ask whether they have had any trouble in any of these areas.

At this point, they will often share a concern. If it involves being stigmatized, I validate the painfulness of that experience: It is wrong, it is real, and it hurts. Then, we talk about ways to productively and safely deal with bias, discrimination, or stereotyping. I offer them these tips:

It is OK to say that a situation feels hurtful. The key is to address the comment or action, not the person.

If the situation involves a person in authority, stay calm, look the person in the eyes, keep your hands visible, and watch your body language. Take note of the person's name tag or other identification, if possible.

Once the situation allows, walk away safely and go talk to a trusted adult who can help you figure out what happened and how to address it.

My intent is to reassure teen patients that I am available to help them and there are other adults who care about them as well and are working hard to change the status quo. We just want them to be safe in the meantime. I also make an effort to praise them for their young creativity and passion, and I encourage them to be involved in activities that make their schools, neighborhoods, and communities better, more inclusive, and just.

As physicians, talking about these issues is our responsibility because stigma and discrimination affect our patients' health. This is not a minority issue; this is our issue. As the late Sen. Paul Wellstone used to say, “We all do better when we all do better.”2