Most organizations want to get better, but most of their improvement efforts fail. Here's why.

Fam Pract Manag. 2017;24(1):17-20

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

The spread of “best practices” is important in today's rapidly evolving health care landscape where quality and outcomes matter more than ever. However, spread can be incredibly difficult to achieve.

One of us (Dr. Toussaint) has visited and observed 174 health care systems in 17 countries. Almost every one of these organizations has undergone significant innovative care redesign in recent years and has attempted to spread that redesign. Most have failed.

The other of us (Dr. Elmer) was a physician leader at ThedaCare Physicians in Kimberly, Wis., when the clinic was chosen to create an ambulatory care redesign, which encompassed the entire outpatient experience. It improved patients' access to care by allowing the use of smart phones for scheduling appointments and asking questions. It changed the way staff planned for upcoming appointments and included “scrubbing” the clinical chart the night before the visit to proactively understand what would happen the following day. It delivered same-day, 15-minute lab turnaround times so that providers would have at hand all lab results essential to determining the next steps in care. All patients were given an after-visit summary upon checkout that clearly documented their lab results, medication changes, follow-up appointments, and future consults. Standards were established for medical assistants to collect all vital signs, perform medication reconciliation, take an updated history, and draw blood before the provider entered the room. This enabled the provider to focus completely on the patient's issues during the visit. In short, it was a remarkable redesign, but it ultimately failed to spread.

In this article, we will explain the core elements of failure to spread and how to avoid making the same mistakes we and others have made.

Four causes of failure

Based on our experience and our observations of other health care organizations, we have identified four common reasons that improvements fail to spread.

1. A top-down approach. The most common reason for failure is using a top-down approach. The leaders write a multipage playbook based on the experience of one pilot clinic, hand it out to the physicians and staff of the remaining clinics, and tell them to implement the playbook. However, the exact standard created in one clinic rarely works in another. The patient demographics are different, the doctors have different interests and practice styles, etc. Applying a top-down, cookie-cutter approach to a complex social enterprise is folly.

Instead, organizations need to include a bottom-up aspect to their change effort; that is, give clinics a playbook not to simply copy but to “copy-improve.” For example, the best practice (or “standard work”) we developed at our clinic in Kimberly was shared with the rest of the clinics, and the physicians and staff were given freedom to determine what was applicable to their individual setting and what wasn't. Each clinic took the standard work and adapted it to its own environment and specific needs.

2. A lack of compelling data. Doctors respond to data. If an organization's leaders cannot produce data showing better results from implementing a change, the physicians will have little interest in making the change. ThedaCare was lucky in this regard; we had the data.

Most providers in the state of Wisconsin report quality measures to the Wisconsin Collaborative for Healthcare Quality (WCHQ). ThedaCare Physicians established the goal of being in the 90th percentile of all groups reporting to WCHQ on 10 specific metrics, including the percentage of patients with an A1C of less than 7 percent. The ambulatory redesign was in place for a few months in 2006 when the group began to exceed quality targets. In addition, net income improved from a loss of approximately $250,000 per year to break even in the first year. Staff satisfaction improved from 75 percent to 100 percent of staff being highly satisfied. Patient satisfaction increased from 40 percent to 70 percent. These results were vitally important for us to begin the process of spread. However, as we learned, data alone aren't enough.

3. Standard work for everyone but providers. The “copy-improve” strategy we implemented (mentioned earlier) was sound, but it had one big gap. There was no detailed written standard created for the providers, perhaps out of concern that providers would get upset if we imposed a standard for their work in the exam room. The standard work for medical assistants, registered nurses, etc., was clearly documented. (See “ThedaCare's ambulatory care redesign.”) But without a documented standard in place for the providers, they simply did what they thought was right, which led to huge variation in the way providers completed their part of the work, with serious downstream implications. Providers began to have their medical assistants trained “their way” rather than having them trained to the standard. They created their own teams rather than using the teams created through the redesign. Cell leads (high-performing medical assistants), the “air traffic controllers of the office flow,” became personal assistants to meet the provider needs, preventing them from effectively monitoring the daily patient flow, deploying staff resources to meet the demands of the day, and helping everyone stick to the standard. It was a workflow meltdown. As problems developed and tasks weren't done to providers' satisfaction (such as the rooming process or the chart scrubbing process), they lost faith in the process and created their own workarounds, often taking back work from staff and doing it themselves. One ThedaCare physician observed, “I am finding I need to keep track of so much more stuff because I can't rely on the process or on the training of the different people who now ‘help’ me take care of patients.”

The result was a gradual deterioration (although not total destruction) of the original Kimberly clinic redesign framework.

If there had been a standard in place for providers' work, they would have been able to use it as a guide and understand why it was important for them to follow certain processes. Starting from a standard is easier than starting from a blank sheet of paper. A standard also would have helped protect providers from taking on others' work or attempting to solve problems that belonged to the team.

Today, all clinics are using plan-do-study-act thinking to develop provider standards, which should benefit both providers and staff. For example, provider standards for the process of answering in-basket messages should save triage staff more than 400 minutes a week in rework, according to data from one of our clinics. Provider standards for the after-visit summary are also a priority because the summary incorporates all aspects of the clinic visit and cannot be effectively created unless everyone on the team does their part.

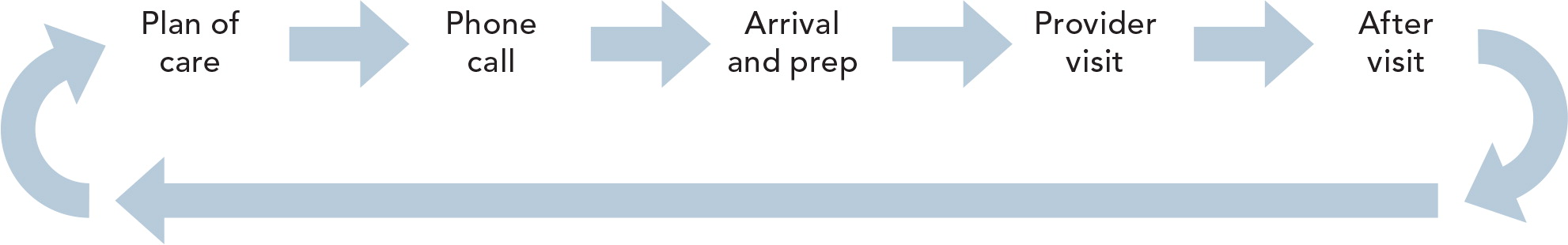

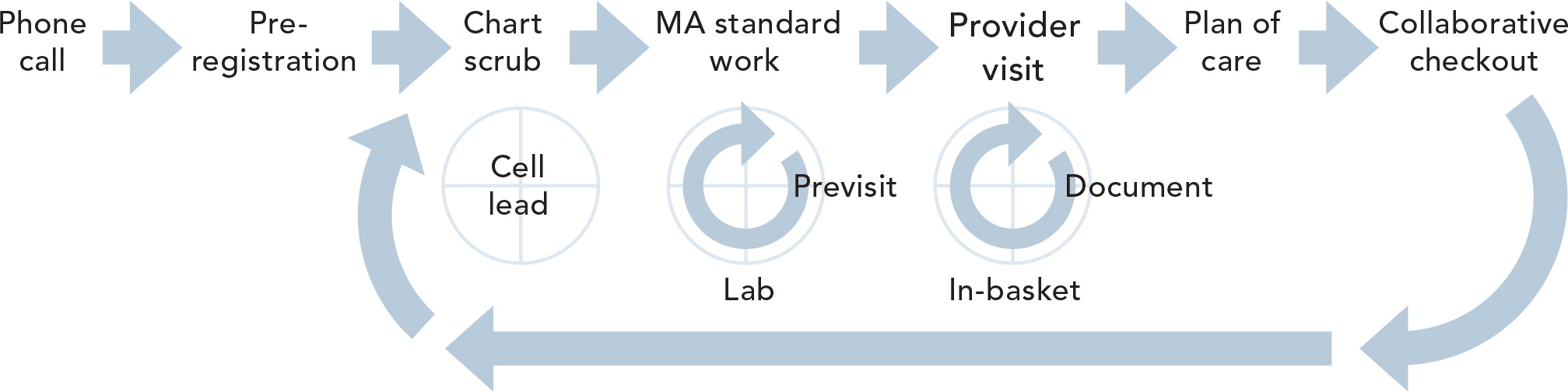

THEDACARE'S AMBULATORY CARE REDESIGN

The following diagrams illustrate ThedaCare's redesigned flow of the patient visit and supporting processes. Standards were created for all of the supporting processes, but the visit component was determined by each provider, which led to a deterioration of the workflow.

4. Lack of management. Ultimately we had to ask ourselves, “How did this decay happen?” We think the root cause was that no management standards were in place.1 These management standards have been well documented elsewhere.2 They include a regular audit process. Management's job is to ensure that work standards are actually being followed. If they are not being followed, management must identify why. For example, staff may require more training, or a standard may need to be updated if staff have identified a new, better way.

Management standards should also include a visual display of key performance indicators so everyone involved can see at a glance how the clinic is doing and a process for identifying staff ideas for problem solving. Typically this is done in a daily huddle. For example, at the Lee Memorial Health System internal medicine outpatient clinic in Fort Myers, Fla., the doctors and staff meet for 15 minutes before clinic each day. They look at how they did the prior day on key metrics such as wait times. Then, they discuss the upcoming day and how to avoid flow problems and other issues. Staff prioritize the ideas and are empowered to solve these problems themselves.

For more complex problems or systemic issues involving many departments or clinics, management should use a rigorous problem-solving approach, such as “A3” thinking.3 This approach focuses on clearly understanding the background and current conditions of a situation, identifying the root problem to be solved, and establishing the target condition before jumping to solutions. The entire story is told on a single sheet of paper, an A3 size, thus the name. (An A3 template can be found online.) This approach entails going to the place where the work is done and getting the facts as opposed to assuming what the answer is. Equipped with information from the front line, management can then recommend an experiment to address the problem.

Moving beyond failure

Failure to spread is common but not inevitable. We have learned that spread using top-down playbooks doesn't work, but the copy-improve approach can work if standards are clearly defined for each team member – including providers – up front. We have also learned that without compelling data and management standards in place an organization cannot sustain and improve on care delivery changes. We have not discussed other possible causes of spread failure. These include physician leadership issues at clinics, management structures that do not allow for physician and staff input, and poor information flow to physicians and staff regarding the changes. There is still much to learn, but as Thomas Edison once said, “I have not failed. I have just found 10,000 ways that won't work.”4