The wrong joke at the wrong time can shatter the doctor-patient relationship, but humor used wisely has health benefits and strengthens bonds in stressful situations.

Fam Pract Manag. 2020;27(2):11-15

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

After Veronica Valdez was sedated for finger surgery at a California hospital in 2011, her anesthesiologist, Patrick Yang, MD, placed stickers on her face so it looked like she had a mustache. Then Yang had a nursing assistant take a picture, which coworkers said they later saw on social media. Valdez also worked at the hospital and, according to the local newspaper, Yang said he thought “she would get a kick out of it.”1

Valdez did not. Instead, she sued Yang and the hospital.

There is a place for humor in health care. While laughter may not always be the best medicine, there is evidence that when used properly it has health benefits and promotes cohesion among coworkers. Sigmund Freud and other psychologists have theorized that laughter relieves inner psychological tension and is a healthy coping mechanism in stressful situations. 2,3 Subsequent research has shown that shared laughter enhances interpersonal relationships and group dynamics.4 Moreover, humor is actually good for us, physiologically. It has been associated with reduced cortisol and catecholamine levels,5 greater endorphin levels,6 and increased immune function.7 Humor can also enhance the patient-doctor relationship and reduce physician burnout.8,9

But misplaced or inappropriate humor can have serious consequences in almost any workplace. Health care, with its strict rules about professionalism and privacy, is no exception. Medical professionals might wonder the extent to which it is appropriate to joke with patients and colleagues, especially in the current sociopolitical climate. Something that makes one person laugh may be offensive to another. It may even irreparably damage a relationship or jeopardize a career.

KEY POINTS

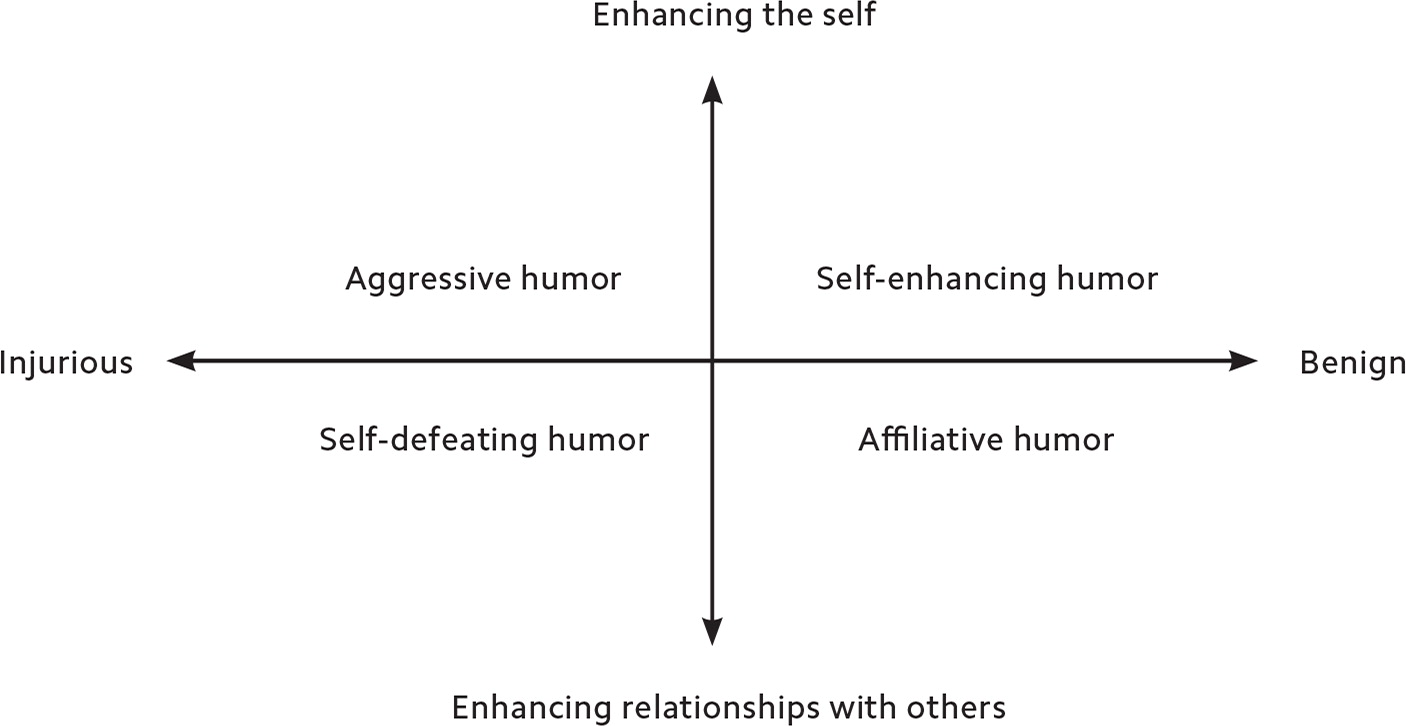

Humor can be divided into four types, two of them benign (affiliative and self-enhancing humor) and two of them injurious (aggressive and self-defeating humor). Benign humor is generally better for professional settings, including medicine.

Affiliative humor revolves around finding common ground by laughing at shared experiences. Self-enhancing humor revolves around laughing at oneself in situations of misfortune, often as a coping mechanism.

Self-defeating humor (disparaging oneself to amuse others) can strengthen bonds if deployed sparingly and in the right context, but aggressive humor (disparaging others) is almost never welcome in the workplace.

How does a physician reconcile these potential upsides and downsides? With humor being so complex and dynamic, how is it safely incorporated into one's professional life while avoiding personal harm? The answer lies in understanding the various types of humor and being able to discern what actually makes individual uses of humor appropriate or inappropriate. It's a little bit like understanding how a particular medication works in order to maximize its benefits while avoiding complications or side effects.

In 2003, University of Western Ontario psychology professor Rod A. Martin and colleagues developed and validated a questionnaire designed for future psychological investigations into the use of humor.10 They created a frequently cited framework that categorizes humor into four styles based on two important distinctions (see “What type of joke is this?”). The first distinction is whether a particular use of humor benefits oneself or enhances one's relationship with others. The second is whether the same humor is considered “benign” or “injurious.” Combining those two questions results in four categories, or styles, of humor: affiliative, self-enhancing, aggressive, and self-defeating.

FOUR TYPES OF HUMOR

In the professional setting it's usually best to stick with the two types of benign humor. According to Martin and colleagues, those are affiliative and self-enhancing humor.

Affiliative humor. This type of humor uses inoffensive jokes that everyone can relate to in order to create a sense of fellowship. It often entails laughing about the small absurdities of everyday life and is considered bonding humor because it enhances interpersonal relationships and safely creates shared laughter. Because it deals mostly with the mundane, affiliative humor often relies on witty commentary, wordplay, and well-timed jokes. The sitcom Seinfeld, often dubbed “a show about nothing,” frequently used this type of humor. For example, an entire episode of the show once centered on the main characters searching for their car in a large parking garage — a situation that was comedic fodder largely because it's something many people can relate to.

In the clinical setting, when a physician buys coffee for the team after an exhausting morning and then jumps up and face-tiously proclaims, “Now I'm ready to see another 50 patients!” that's an example of using affiliative humor to relieve tension and improve group dynamics.

Self-enhancing humor. This is the second form of benign humor. It could also be described as self-reflective or internal humor. It focuses on finding amusement in one's personal situation and the incongruities of life. It is consistent with Freud's explanation of humor as a healthy coping mechanism. Self-enhancing humor includes the ability to laugh at yourself in times of misfortune. It finds levity in the idiosyncrasies of everyday life, helping to maintain a positive perspective and potentially reduce burnout. A physician who is moving through the copious clicks needed to navigate an electronic health record system might suddenly stop, flex her wrists and say, “I wonder what the ICD-10 code is for carpal tunnel syndrome?” That's using self-enhancing humor to cope with a frustrating situation.

On the other side of the benign-injurious axis lies aggressive humor, which is almost never advisable in professional settings, and self-defeating humor, which can be OK in small doses.

Aggressive humor. This type of humor is typically used to enhance the self and “get a rise out of the crowd” at the expense of others. It is denigrating and disparaging, and therefore harmful. Examples include mockery, teasing, and ridicule. There is an example of this in the 1996 movie The Nutty Professor, when a stand-up comedian played by Dave Chappelle mercilessly humiliates an audience member with crude jokes about his obesity. Aggressive humor is consistent with the superiority theory of humor, originally proposed by Thomas Hobbes, which proposes that laughter is grounded in the shortcomings and misfortune of others.11 Aggressive humor is detrimental to group dynamics, undermining trust and true cohesion. Sexist and racist jokes fall within this category and obviously should be avoided. But jokes about a person's weight, height, clothing, or hair-style that seem more benign could also be aggressive and injurious and are similarly ill-advised.

Self-defeating humor. This type of humor relies on self-disparaging jokes, with the goal of ingratiating oneself or gaining approval. It is an attempt to strengthen group relationships at the expense of the self. The comedian and actor Rodney Dangerfield is the classic example of this, having built his career around stories about how he gets “no respect.” Within a clinical context, such humor could undermine a patient's confidence in a provider's ability to provide excellent care. In a recent AT&T commercial a surgeon who is “just OK” at his job strides into a patient's room and says, “Guess who just got reinstated? ... Well, not officially.” While it's funny as a satirical commercial, trying to replicate that joke with a patient would probably not be a good idea.

On the other hand, self-defeating humor used sparingly and in the right context, may be a safe way to bolster the doctor-patient relationship. For instance, if a patient asked a particularly thin physician how his weekend went and the physician dryly told the patient, “It was great. I won a weightlifting competition,” that's probably something both of them could laugh about.

Humor may not always fit neatly into these four styles. Self-deprecation in moderation may be self-enhancing and affiliative, but when used excessively it can slide into the self-defeating category and be detrimental to both the user and the group. Similarly, gallows humor — joking about painful, serious, or frightening subjects in lighthearted or satirical ways — can be aggressive and injurious, but if used only in proper settings, it can be benign, or even group-enhancing. Some research shows that gallows humor can relieve tension among individuals facing highly stressful circumstances, including medical professionals.12 The danger with gallows humor, though, is when the object of the humor is a member of the team or community. In such cases, the humor becomes aggressive.

Despite these nuances, evidence generally supports sticking to the benign side of the humor classification scheme in professional settings. Since Martin and his colleagues developed the scheme, more research has applied it to humor in those settings, including medicine. One study found that self-defeating humor was associated with symptoms of depression, while self-enhancing humor was inversely correlated with those symptoms.13 Another study found that affiliative and self-enhancing humor are positively associated with work engagement and negatively associated with burnout.14

PRACTICAL STRATEGIES

There are other theories of humor to consider. Comic theory, originating in ancient Greek theatre, classifies comedy as either “high” or “low.” High comedy — similar to affiliative humor — typically involves clean, witty jokes that many people can relate to and may require a certain level of intellectual insight to be appreciated. Low comedy requires less intellectual insight and can include boisterous joking, buffoonery, general misrule, and slapstick humor. Low comedy may also incorporate elements of Hobbes' superiority theory when it comes at the expense of others. In health care and other professional settings, one should aspire to use high humor and avoid low humor. But high humor should never alienate or embarrass those who may not understand a joke or witty comment because of language barriers or intelligence level.

Less theoretical, more practical strategies for using humor in the professional setting include the following:

Make fun of yourself first. This is a strategic use of self-defeating humor in an affiliative fashion. It avoids being aggressive while also allowing a glimpse into a patient's or colleague's receptiveness to humor. But remember, too much self-defeating humor may erode respect and even harm group dynamics.

Be subtle. Subtle witticism belies intelligence and generates respect.15 Furthermore, it is usually affiliative and not distracting. It does not unduly interrupt a discussion or dialogue.

Be careful with politics. Politics are increasingly divisive and polarizing. Political humor will therefore often be interpreted as aggressive in nature, even if it's not meant that way.

Know the audience. As noted, some may laugh at a seemingly witty comment, and others may not. An orthopedic surgeon giving Grand Rounds may draw laughter from the crowd with a joke about podiatrists. This aggressive humor will backfire, however, if a podiatrist is present.

Be competent and use humor in moderation. If one is funny but clinically inept, the use of humor will undermine respect and the effectiveness of a joke or witty comment. The same holds true when humor is used too frequently during an interaction or within a relationship.

When used properly, humor can enrich relationships with colleagues and patients alike, and understanding the various styles and forms of humor will help physicians safely use humor in the clinical setting. Aggressive humor and low humor should be avoided, while affiliative humor and high humor should be emphasized. Self-defeating humor used in moderation may also be beneficial. But whatever type of humor you employ, make sure it's consistent with the physician's oath to first, do no harm.