DPC Doc Shares Vision in State Leadership Role

September 23, 2019 01:12 pm David Mitchell – Molly Rutherford, M.D., M.P.H., has a small patient panel compared to that of many family physicians, and that's just fine with her. One hundred of her roughly 450 patients are being treated for addiction, so they visit her as often as once a week.

"I'm good with where I am," said Rutherford, a direct primary care practice owner in Crestwood, Ky. "With addiction treatment, I see people more often. My schedule isn't typical."

Rutherford tried typical practice models. They weren't for her.

The family physician's first job after residency was in a hospital-owned health system. That practice, which was in a rural setting, offered student loan repayment, and Rutherford found a niche she enjoyed, helping patients struggling with addiction. She got a waiver to prescribe medication-assisted treatment and started with a group of 30 patients.

"Once I started prescribing buprenorphine," she said, "I saw what could happen in people's lives."

After that first year, she asked her employer if she could increase the number of people she was treating for addiction to 100 patients, but the hospital system, citing low reimbursement, said no.

She eventually moved to practice closer to her home, working for a patient-centered medical home while also moonlighting at an addiction clinic. She chafed at the lack of control over her own schedule at the PCMH and the need to see patients at 10- to 15-minute intervals.

"I was frustrated with not being able to take care of patients the way you should," she said. "I felt like I wasn't able to do a good job. I wasn't able to sleep worrying about what I might have missed."

That practice offered a stark contrast to her work in addiction treatment, which was gratifying not only because of the effect it had on patients' lives but because the cash-pay model was so much simpler.

"I really liked that," she said. "I could focus on spending time with my patient, just listening. I didn't worry about checking boxes or justifying what I did for third parties."

In 2014, Rutherford started sharing space with an addiction counselor while also working at the PCMH. But after reading about what Josh Umbehr, M.D., was doing in the relatively new DPC model in Wichita, Kan., Rutherford realized that a simpler model of primary care was what she wanted. In 2015, she combined her addiction clinic with a DPC practice in one location.

"I felt like that was the way I wanted to practice medicine," she said. "When I was in residency, I was told doctors can't run a business. Well, no one can make sense of what's happening now with billing and getting checks in the mail that literally are for pennies. It's just not working. Transitioning to direct primary care has been awesome for me. I'm really glad I did it."

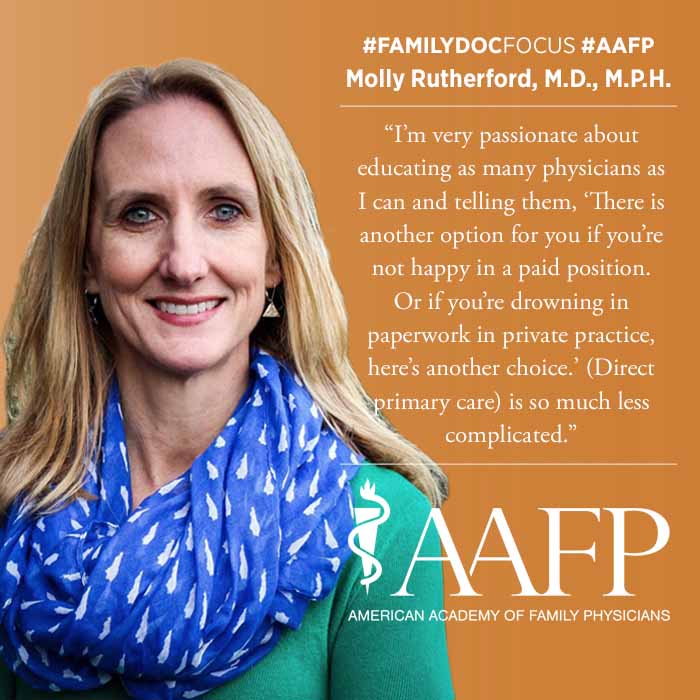

Rutherford recently completed her term as president of the Kentucky AFP and transitioned to the role of Board chair. As a DPC physician in a state leadership role, she's somewhat unique, and she's used that platform to share her vision.

"Having done this for four years, it's very evident that a huge part of the health care system's problem is having so much power in the hands of third parties," she said. "I'm very passionate about educating as many physicians as I can and telling them, 'There is another option for you if you're not happy in a paid position. Or if you're drowning in paperwork in private practice, here's another choice.' DPC is so much less complicated."

She's also passionate about convincing more family physicians to offer MAT.

"If you're a family physician, you're already treating nicotine addiction," she said. "It's not that much different. Get a mentor if you're not sure about it. You don't have to have a huge number of patients. Get your feet wet and figure it out over time. Some physicians think MAT is trading one addiction for another. It's good for them to hear from another physician that is not the case."