Setting an Example for Native Youth

June 01, 2020 01:39 pm David Mitchell – An elderly Native American patient was being less than forthcoming with her physicians one summer day at the Northern Navajo Medical Center in Shiprock, N.M. When Clint Brayfield, M.D., walked into the exam room, everything changed.

"I introduced myself in Navajo, and I could see her relax," said Brayfield, who had just finished his first year of medical school at the time. "She had put up walls with other providers. After my interaction with her, we realized she had initially left out information. When she told it to me, it changed our management of her diabetes. It was interesting to see. There really is distrust of Western medicine in the Native American community."

Brayfield gets it. He grew up with a father who struggled with bipolar disorder and often was unable to get the help he needed.

"I want to help others who had been in situations like mine," he said.

Brayfield's situation involved moving a lot as his family -- including seven siblings -- coped with his parents' financial, legal and medical issues.

Roughly 65% of Native Americans finish high school, and less than 10% graduate from college -- far below national averages in both categories. Brayfield overcame those odds and became the first person in his family to graduate from college. He was accepted into the University of New Mexico's combined B.A./M.D. degree program, which accepts 28 students per academic year from state high schools and the Navajo Nation who are committed to becoming physicians and practicing in the state. Students receive financial support and a conditional admission to medical school.

Brayfield recently completed the program and will stay at UNM, where he matched in the family medicine residency. He chose UNM, in part, because the program allows residents to work at an Indian Health Service clinic.

"Matching at UNM and having the ability to work at an IHS clinic is important to me because it allows me to provide care for Native American patients right now instead of having to wait until after residency to do so," he said. "In addition, gaining experience with the IHS system would allow me to be more efficient when I am an attending physician working for IHS, and gives me insight into how I can impact the system for the better."

Staying also will allow Brayfield to continue being involved with projects he was working on during the past academic year (before they were stalled by the pandemic), when he was president of the UNM Association of Native American Medical Students. The group is working on a mentoring program for pre-med Native American students and also is trying to implement curriculum regarding Native American health.

Those initiatives are important, Brayfield said, because Native Americans represent 11% of the state's population. Nationally, Native Americans account for roughly 2% of the population but only 0.4% of the U.S. physician workforce.

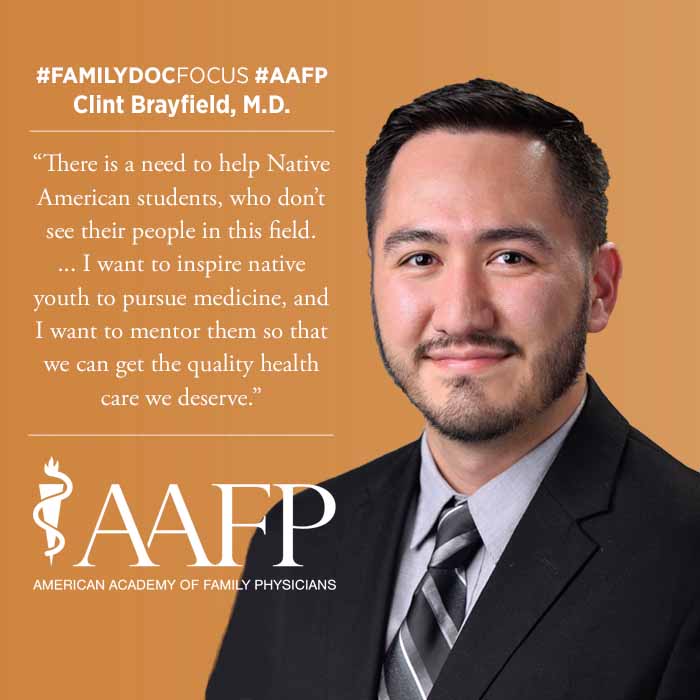

"There is a need to help Native American students, who don't see their people in this field," he said. "They need to be mentored by people who know where they're re coming from and have shared experiences."

Brayfield said he ultimately hopes to practice broad-scope family medicine at an IHS facility on a reservation.

"I want to inspire native youth to pursue medicine," he said, "and I want to mentor them so that we can get the quality health care we deserve."