Veteran FP Expanding His State's Physician Pipeline

June 08, 2020, 01:41 pm David Mitchell – John Mitchell, M.D., could have retired by now. His work in family medicine -- his second career -- spans parts of five decades, but some of his most important work in the specialty is yet to come.

"I don't want to leave when we have so much going on," said Mitchell, director of the Office of Mississippi Physician Workforce.

It wasn't that long ago that there wasn't nearly enough going on in family medicine in Mississippi. Things started to change in 2010 when the William Carey University College of Osteopathic Medicine opened in Hattiesburg. The state's second medical school has steadily increased its class size, which is expected to reach 200 by 2022. Meanwhile, the University of Mississippi, which traditionally accepted 100 students per year, upped its class size to 165 last year.

The imminent boom in medical school graduates is needed in Mississippi, but can the state absorb such an influx of interns? In 2012, the state had only two family medicine residency programs. It ranked 43rd in the nation in residents and fellows per capita and last in physicians per capita.

During his campaign for governor in 2011, (then) Lt. Gov. Phil Bryant said the state needed to drastically increase its physician workforce. The Mississippi AFP seized on the opportunity and initiated the development of H.B. 317, which created the Office of Mississippi Physician Workforce and established funding to support new residency programs during the creation and accreditation process. Bryant signed the bill, which authorized up to $3 million per program, three months after he took office in 2012.

Mitchell initially served on the OMPW Advisory Board and was named the program's director in 2013. Under his direction, the state has launched two new family medicine programs (in Hattiesburg and Meridian), with a third set to welcome its first crop of interns in July in Greenville. Mississippi has seen its number of family medicine residency positions more than double to 38 per year. Pending approval by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, two more programs -- in Gulfport and Southaven -- could bring that number to 54 residents per class by 2022.

Yet another family medicine program in development, a cooperative effort with Meharry Medical College, would have residents train in both Nashville, Tenn., and Clarksdale, Miss. That program would have three residents per class and could be up and running as soon as next year, Mitchell said.

In addition to the family medicine programs, Mississippi has seen the accreditation of new emergency medicine and internal medicine programs since 2012. Additional emergency medicine, internal medicine and psychiatry programs are under development. The new programs are spread across the state, which traditionally has ranked among the worst in the country in terms of access and outcomes.

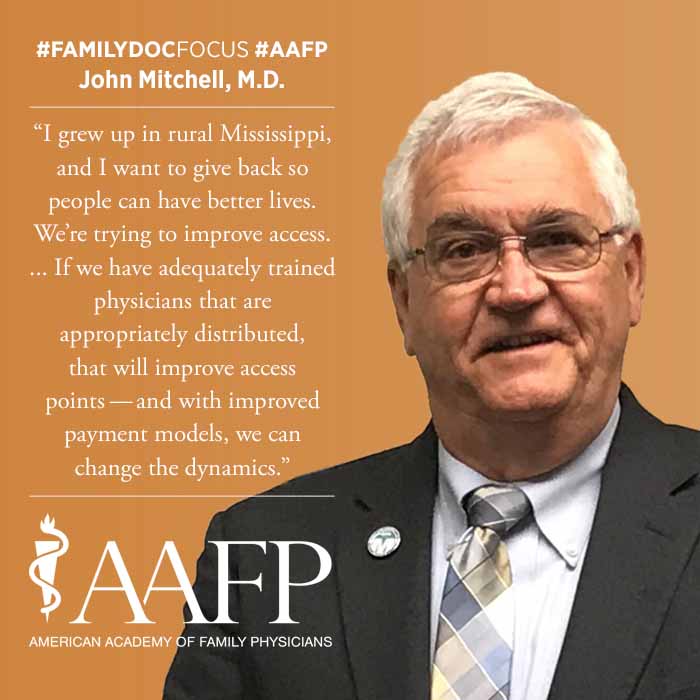

"I grew up in rural Mississippi, and I want to give back so people can have better lives," Mitchell said. "We're trying to improve access. Primary care and family medicine are best equipped to manage population health. If we have adequately trained physicians that are appropriately distributed, that will improve access points -- and with improved payment models, we can change the dynamics."

Payment is a hurdle to physician retention and access in Mississippi. The state did not expand Medicaid, which Mitchell said has had an impact on payment, especially in rural areas. But he's taking the challenges "one domino at a time."

His role in this process has included identifying "naive or virgin" hospitals that are eligible for CMS GME funding, meeting with leadership of eligible institutions and convincing them that GME training is a good investment.

"It's almost like fishing," he said. "When you catch one, you try to not let that one get away."

Beyond those initial hurdles, he also had to create buy-in among medical staff and identify and recruit program directors.

Mitchell is especially excited about the Mississippi Delta Family Medicine Residency Program, which will open next month in Greenville, because the area is among the most impoverished and underserved in the state.

"It's going to be a great opportunity for residents to train in population health and learn about inequity and reaching out to change the disparities in the region," said Mitchell, who also is a member of the AAFP's Commission on Education.

Mitchell, who will turn 70 in January, worked for almost a decade as a pharmacist (including three years in the U.S. Army) before he found his true calling. Being a pharmacist in a hospital made him want to become a doctor.

Mitchell gave up his patient panel five years ago, but he's not done working yet.

"These programs are like my babies," he said. "I want to see them grow and get to a point that they are stable and mature."