Deaf Family Physician Aims to Improve Communication

October 5, 2020, 3:11 pm David Mitchell -- When she arrived in Rochester, N.Y., for the first time, Carolyn Stern, M.D., stopped for gas and got a pleasant surprise.

"I went inside to pay, and the person working there was signing to me even though she was hearing," said Stern, who is deaf. "I went to stores and the clerks were signing. It's a very welcoming community."

As an advocate for people who are deaf and hard of hearing, Stern has given presentations across the country. But there was something different about Rochester, which, as home to the Rochester School for the Deaf and the National Technical Institute for the Deaf (one of nine colleges at the Rochester Institute of Technology), has one of the nation's largest per capita population of people who are deaf.

After a workshop there, Stern was approached by a recruiter looking for physicians interested in caring for patients who are deaf. She relocated with a five-year commitment in mind and is still there 22 years later.

Things have not always been so simple. Stern was born with a severe-to-profound hearing loss in her left ear and a profound hearing loss in her right ear. Her parents were warned not to have high expectations for their child by professionals who deemed young Carolyn "slow." She was bullied in middle school and had to wage a legal battle to receive interpreter services as a student at the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. As a resident at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill., Stern became completely deaf and adapted with a cochlear implant.

"There were a lot of challenges," she said. "It took a lot of navigation."

Stern has tried to make things easier for others with hearing loss through her website, DeafDOC.org, which offers free health information and dozens of sign language videos for the deaf and hard-of-hearing community, health and educational professionals, and interpreters. The website aims to improve communication between physicians, interpreters and patients.

"I hope to improve health literacy," she said. "I have so many patients who are deaf from birth. Many can't even communicate with their families."

Stern had more hurdles of her own to clear even after completing her training and earning her medical license.

"Some CME providers refused to provide accommodations," she said. "Some programs closed workshops rather than provide interpreters."

Stern voiced her concerns to the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education, which hired her as a consultant. In the early 2000s, she taught thousands of CME providers about accommodations, speaking several times a year for hospitals, urgent care centers, medical societies and others who want to provide CME.

"To be a CME provider, you have to take the full coursework given by the ACCME," she said. "It's definitely changed a lot."

She said CME can still presents challenges for physicians who are deaf and hard of hearing. During the pandemic, live events largely have been replaced with online courses.

"Video and online CME still lacks accommodation," she said. "I'm going to have to start talking to the ACCME again."

COVID-19 also presents challenges in the clinical setting for health professionals who are deaf and hard of hearing.

"It's been difficult with everyone wearing masks," said Stern, who practices at the UR Medicine Urgent Care centers in Rochester, where she also supervises advance practice providers and serves as clinical faculty for nurse practitioner students. "I now have a sign language interpreter full time. I don't like that I've lost my sense of independence in patient interactions."

Stern also is the medical director and school physician at the Rochester School for the Deaf. In that role, she supervises four nurses who work in the student health center; is involved in the COVID-19 school reopening plan, performs health exams and evaluations; and presents educational programming for students, parents and staff.

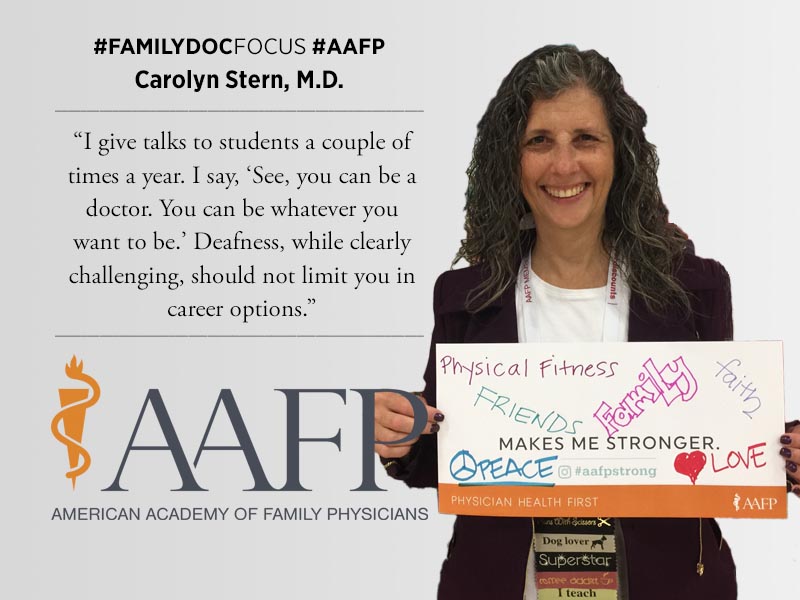

Stern also wants to be a role model for students.

"I give talks to students a couple of times a year," she said. "I say, 'See, you can be a doctor. You can be whatever you want to be.' Deafness, while clearly challenging, should not limit you in career options."