Difficult Transition Led IMG to Leadership Roles

April 18, 2022, 3:53 p.m. David Mitchell — Rashmi Rode, M.D., had been a practicing gynecologist for six years when she decided to start over with a second residency, a new specialty and a new country.

Due to her husband’s service obligation in the Indian Armed Forces, Rode’s family moved frequently. New posts for her husband meant new jobs for her and new schools for their children. Rode, who was senior faculty in obstetrics and gynecology at the Government Medical College & Hospital in Chandigarh, India, was eager to settle in one place.

“I was working with a group of medical students who were preparing for the United States Medical Licensing Exam,” she said. “One of them said, ‘Why don’t you try, because you have such strong basic knowledge? If you have to settle down, why not settle down in America where you would have more opportunities for your kids?’ I had a very steady job at the time, but still, I took a chance.”

Rode had excellent test scores during the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates certification process and matched at the family medicine residency at the Baylor College of Medicine in Houston.

“Since I had done the previous training in OB/Gyn, I did not want to do the same training again,” said Rode, who is an assistant professor in Baylor’s Department of Family and Community Medicine and associate director of the family medicine residency. “I felt like I already had expertise in that subject. Family medicine definitely increased the breadth of my training.”

Rode embraced the challenge of starting a new career path. More difficult was the challenge of moving her family. Rode’s children stayed in India for a year with their father while she started residency and adapted to life in Texas. The children arrived in 2009 in time for her daughter and son to start second and ninth grades, respectively.

“They were both born in India, and for them, it was a huge transition coming to a different country,” she said.

Her husband, due to his military commitment, visited frequently but was unable to make a permanent move until 2013.

Rode had worked with an underserved population in India and found similarities with the patients she was seeing in Houston.

“There was a lot of patient education, and I really enjoyed helping them understand what we are going to do,” she said of her patients in India. “When I came here for my training at Baylor, it was the same. Yes, they spoke a different language, but it was very much a similar population where you have to literally make sure that the patient understands and engage them in their own care to get good outcomes.”

Rode realized many of her patients could not understand their after-visit summaries, which led her to work with colleagues in related quality improvement projects. Those efforts led her to participate in the Texas AFP’s Family Medicine Leadership Experience, a yearlong development program.

She now serves on multiple TAFP committees and is president-elect of the Harris County AFP. She will be in Kansas City, Mo., April 28-30 as a co-convener of the international medical graduate constituency during the AAFP’s National Conference of Constituency Leaders, a development event for women, minorities, new physicians, IMGs and LGBTQ+ physicians or physician allies.

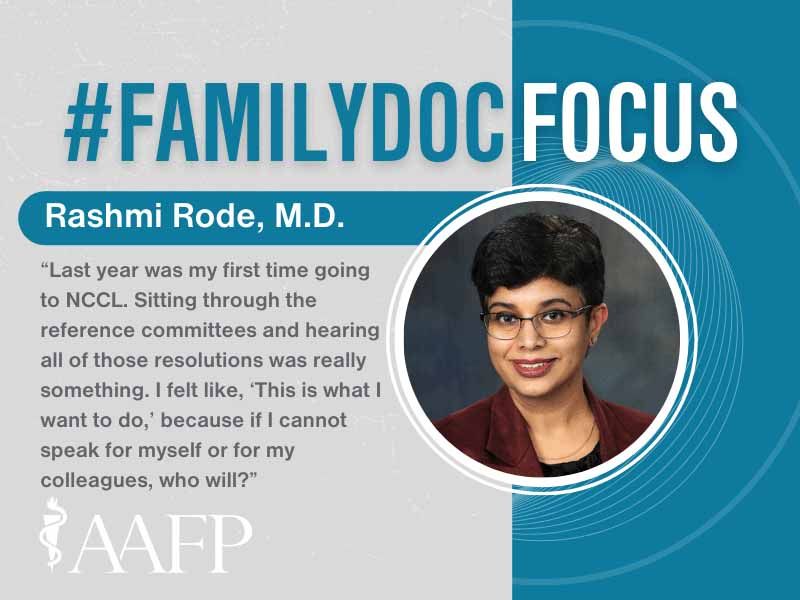

“Last year was my first time going to NCCL,” Rode said. “Sitting through the reference committees and hearing all of those resolutions was really something. I felt like, ‘This is what I want to do,’ because if I cannot speak for myself or for my colleagues, who will? I don’t consider myself as an eloquent speaker, but yes, I can share what I have gone through. People relate to personal stories.”

Rode has plenty of stories when it comes to the travails of an international medical graduate.

“My reason for getting involved in the IMG constituency is how difficult it is to transition,” she said.

Rode’s elder child graduated from a Texas high school and the University of Texas, but he was considered an international student when applying to U.S. medical schools. The options for such students are limited.

“The state of Texas does not allow international students to even apply to medical schools in Texas,” Rode said.

Her son enrolled instead at an out-of-state U.S. medical school. Students who are not U.S. citizens or who do not hold a permanent resident visa status are not eligible to receive financial aid. The school required the Rodes to document that the necessary funds were available in an escrow account to pay the costs of tuition and fees for four years, or roughly $275,000.

“We liquified all our savings back home in India, and whatever I had here, to make sure that we had that amount upfront deposited for him to pursue medical school,” said Rode.

Meanwhile, Rode’s younger child has been offered a summer internship in California, but the offer is contingent on obtaining an Employment Authorization Document, or green card. Her child will soon be 21, the age when a person is no longer eligible to obtain permanent residency based on a parent’s visa.

“All those things I find very limiting and stressful,” she said. “I made the transition to come to the United States so that my kids would have better opportunities. But when you see these opportunities being curtailed because of a visa, it’s really disappointing.”

Rode came to the United States on a J-1 visa and has since obtained an H-1 visa. Her green card was approved in 2012 but has not been issued yet.

“I have to get my permanent residency before thinking of becoming a citizen,” she said. “So, I’m still waiting, and I cannot tell you how many times I have written letters to the senators. I’m involved in all these advocacy groups to push for this.”

Rode is not one to give up. Her path to becoming a physician started at age 5 when she fell from a third-story balcony. A compound fracture of the femur led to a three-month recovery in the hospital where the relationships she formed with physicians and nurses made a lasting impact.

Rode was initially told that she likely would not be able to walk again, but she progressed from using a wheelchair, to walker, to crutches and eventually walking without an aid.

“I really experienced the loving care that they showed to a small child,” said Rode, who eventually returned to the same hospital as an intern. “They were supportive and tried to see what I liked and would even spend time with me, not just providing medical care but also sitting down with me to play games, anything that kept me engaged. I saw how they went above and beyond, not just treating me with medications or physical therapy, but also making sure that my spirits remained high.”