AAFP Humanitarian Award honors commitment to refugees in Uganda

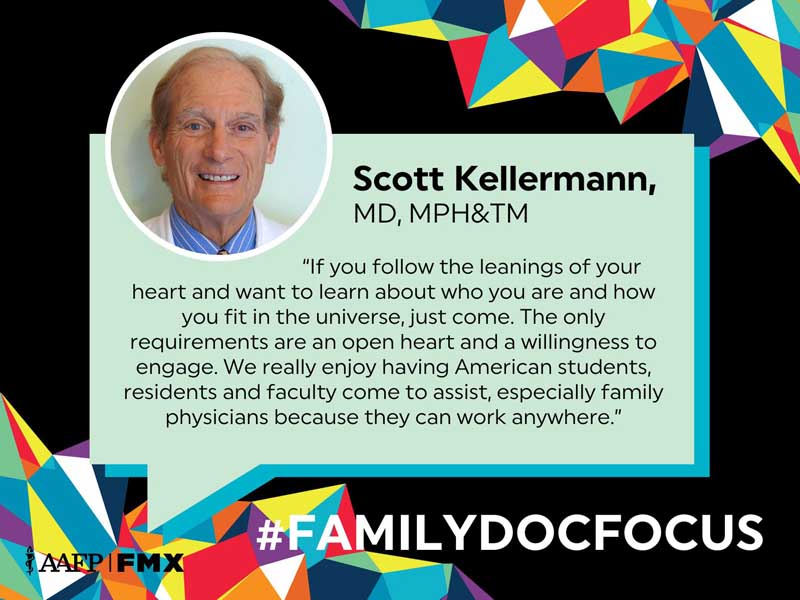

Oct. 9, 2025, David Mitchell—Scott Kellermann, MD, MPH&TM, has a message for those interested in global health: Don’t overthink it, just follow your heart.

“If you follow the leanings of your heart and want to learn about who you are and how you fit in the universe, just come,” said Kellermann, who received the Humanitarian Award Oct. 5 during the AAFP Congress of Delegates for his efforts in Uganda. “The only requirements are an open heart and a willingness to engage.

“We really enjoy having American students, residents and faculty come to assist, especially family physicians because they can work anywhere: outpatient clinic, surgery, OB/Gyn, public health or to advise on our NIH research projects. There’s a panoply of things you can do as a family physician.”

When Kellermann was a young physician looking for a place to serve in the late 1970s, he wrote to multiple hospitals and agencies indicating that he would be willing to practice without pay for two years.

“We received a 3-foot stack of mail,” Kellermann said. “It was obvious that hospitals in the developing world were keen on having a free doctor.”

Kellermann and his wife, Carol, stored their belongings and embarked on a six-week trip abroad to ponder their next move. While they were gone, thieves stole or destroyed almost everything, including his mail.

Only a single letter remained on the floor of the storage unit. It was from a hospital in Nepal, making the relocation decision simple.

“The two and a half years we spent at Shanta Bhawan Hospital in Nepal were some of the best of our lives,” said Kellermann, who moved to Nepal with Carol and their 1-year-old child. A second child was born during their time there.

In 1981, the young family relocated back to the United States and settled in Nevada City, California, where Kellmann practiced for two decades. His philanthropic work continued in his new community.

“A friend invited the doctors in our area to his house for dinner,” he said. “After dinner, my friend asked, ‘You might wonder why I invited you tonight. We need to find a way to assist the indigent patients in our region. There is an abandoned hospital for sale, which we can utilize for this purpose. What do you think?’ In unison, doctors checked their watches. ‘Wow, it’s getting late, gotta run.’”

Kellermann wasn’t dissuaded.

He and two partners bought and renovated the 35-bed facility near his clinic, eventually turning it into a federally qualified health center.

“We were digging deep in our pockets to pay for staff and medicine,” he said. “It took years to get it going. It was exciting. Currently, it is the largest purveyor of health care in the region. It was a true adventure.”

New streamlined nomination process now open

A new application process makes it easier to nominate yourself or a colleague for the Humanitarian Award and other AAFP recognitions.

Talk to Kellermann, and you’re bound to hear that word: adventure.

Instead of flying directly to Nepal for that first mission, his family flew to Germany, bought a Volkswagen van and drove through Europe, across the Middle East and into Asia, toting a 1-year-old.

Why?

Why not?

“I thought the trip would take three weeks,” he said with a laugh. “It took four and a half months. It was a real adventure.”

The Kellermanns enjoyed Nepal so much that when they returned to the United States, the family spent weeks, sometimes months, each summer volunteering at missions in Central America, South America and Asia.

In 2000, an opportunity arose to perform a medical survey of the Batwa tribe, which had been evicted from Uganda’s Bwindi Impenetrable Forest when it became a World Heritage Site to protect endangered mountain gorillas.

The Kellermanns' survey indicated that 38% of Batwa children would not live to celebrate their fifth birthday. Average life expectancy was estimated to be only 28.

Despite being removed from their ancestral home and living in extreme poverty, the people had an “infectious joy,” Kellermann said.

“Every day we woke up to singing and drumming, and fell asleep to the same,” he said.

Kellermann had suspected that eventually one of their overseas locations “would stick.” He was surprised when it turned out to be Uganda.

After a month there, Carol told her husband over dinner, “I feel like I’ve come home.” She later said she thought the Batwa would cease to exist unless something was done, and that her family should be the ones to do it.

They had connected with the locals and vice versa.

The Kellermanns once again bid farewell to most of their possessions. This time, on purpose.

Kellermann turned his practice over to colleagues. They sold their homes, squeezed into a 500-foot abode and moved most of their possessions into storage—again.

When his wife expressed regret several months later about not having many of their possessions, Kellermann suggested that they write down the items they could remember and jettison the rest.

“We could only remember about 20% of our stored possessions. We either gave away or had garage sales on the other 80% of our stuff. It was very freeing,” he said.

Challenges abounded when they relocated to Uganda in 2001. There were no hospitals or clinics in the region, so for the first few years they lived in a tent, traveling and learning the local language, culture and traditions.

“As I was the only physician in an area of 250,000 inhabitants, we practiced mobile medicine. We drove to where a path headed to the jungle, walked a distance along the trail and finally unpacked our supplies under a large, spreading fig tree. Drums would announce our arrival and patients began drifting in,” Kellermann said.

“We typically treated 200 to 500 patients per day. Our ICU was under the shade of the tree. We hung IVs from its branches dripping lifesaving quinine into the veins of kids suffering from cerebral malaria.”

Eventually, the Kellermanns bought land in Uganda and established programs to improve conditions for the Batwa, building homes, primary schools, a hospital and clinics. They also initiated income-generating projects, and water and sanitation projects. Addressing extreme poverty requires a broad-based approach, Kellermann said.

People gather at an outdoor clinic under a fig tree organized to provide treatment to hundreds of people a day..

A nursing school in Uganda started by the Kellermann family plans to expand its work.

And Kellermann is still doing it. His family started three primary schools, which enroll more than 1,500 children, and a nursing school that serves more than 450 students.

The nursing school is expected to transition soon to a full university with the vision of educating thousands of students.

The hospital they founded is now an award-winning 155-bed institution overseen by 12 Ugandan doctors and a staff of 250. Physicians and residents from the United States frequently assist with the work.

“My skills are in medicine, not human resources, construction or administration,” Kellermann said, “but people have come alongside and added their expertise.”

Kellermann, an assistant professor at California Northstate University College of Medicine and an adjunct professor of public health and tropical medicine at Tulane, now splits his time between Uganda and the United States.

At 80, he has no plans to retire.

“You’re supposed to begin with the end in mind,” he said.

“If I did that, I never would have gone overseas, for the journey has been daunting and the results beyond my wildest expectations. I have one rule: Every day, find joy. If you’re not finding joy, something is amiss. As long as it remains joyful, count me in.”

The Kellermanns regularly take their volunteers to the nearby game park that's home to elephants, tree-climbing lions and hippos. At their forest guest house, mountain gorillas visit every few weeks.

Bwindi Community Hospital operates with local physicians as well as physicians and residents from the United States.

Hippos and other wildlife roam a game park near Bwindi Community Hospital in Uganda.

Kellermann knows his path isn’t for everyone, but he has no regrets.

On his long trip across Asia to Nepal, Kellermann met the Dalai Lama. Recognizing his Christian commitment, the Dalai Lama urged him to follow his heart by caring for refugees, and people who are unfortunate or scorned.

“The Dalai Lama’s advice changed my life,” Kellermann said. “In Nepal I initiated a clinic for Tibetan refugees and now in Uganda, I work with the Batwa, who are conservation refugees from the forest. We were warmly welcomed by the Nepalese, the Tibetans and the Batwa. They opened their hearts to us and made us feel at home.”

He acknowledged that it doesn’t sound sensible to sell everything and live in a tent overseas. “But if you’re looking for joy, it makes perfect sense,” he said. “There is inestimable joy in engaging in an endeavor that resonates with who you are and which also meets a need in the world.”