Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(5):1023-1034

See related patient information handout on celiac disease, written by the author of this article.

Celiac disease is a genetic, immunologically mediated small bowel enteropathy that causes malabsorption. The immune inflammatory response to gluten frequently causes damage to many other tissues of the body. The condition is frequently underdiagnosed because of its protean presentations. New prevalence data indicate that symptomatic and latent celiac disease is present in one of 300 people of European descent. Age of onset ranges from infancy to old age. Symptomatic presentations include general ill-health, as well as dermatologic, hematologic, musculoskeletal, mucosal, dental, psychologic and neurologic diseases. Celiac disease has a 95 percent genetic predisposition and, thus, it is frequently associated with autoimmune conditions such as diabetes mellitus type 1 and thyroid disease. Untreated patients have an increased incidence of osteoporosis and intestinal lymphoma. Excellent diagnostic screening tests are now available, including those that detect antigliadin and antiendomysial antibodies. Therapy with a gluten-free diet is effective, resulting in complete resolution of symptoms and secondary complications in almost all patients. Local and national celiac-sprue associations facilitate care of patients with celiac disease and support dietary compliance.

Celiac disease is a gluten enteropathy occurring in both children and adults. The condition is characterized by a sensitivity to gluten that results in inflammation and atrophy of the mucosa of the small intestine. Clinical manifestations include malabsorption with symptoms of diarrhea, steatorrhea, and nutritional and vitamin deficiencies. Secondary immunologic illnesses, such as atopic dermatitis, dermatitis herpetiformis, alopecia and aphthous ulcers, may be the primary presentation.

Prevalence

The magnitude of the prevalence of celiac disease has only recently been recognized. A large multicenter study,1 promoted by the European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition (ESPGAN) and involving 36 centers from 22 countries, has provided important information on the incidence of celiac disease. The average incidence was found to be one case in every 1,000 live births, with a range from one in 250 to one in 4,000. When the age of diagnosis was included in the incidence density of celiac disease, the predicted rate was one case in every 300 newborns.2 Among blood donors, the prevalence of asymptomatic celiac disease was found to be as high as one in 266.3

In the United States, people with the same genetic background as the European population in that study would be expected to have a similar incidence of celiac disease. To determine the prevalence of celiac disease in the United States, 2,000 healthy blood donors were screened for IgA and IgG antigliadin antibodies.4 Those with elevated levels were tested for antiendomysial antibodies. The prevalence of elevated antiendomysial antibody levels in healthy blood donors in the United States was found to be 1:250. This rate is similar to the prevalence in Europe, where subsequent small intestine biopsies have confirmed celiac disease in all patients testing positive for antiendomysial antibody (positive predictive value: 99 percent).5 The authors of the U.S. study4 conclude that data suggest that celiac disease may be greatly underdiagnosed and is relatively common in this country.

The incidence of celiac disease in relatives of celiac patients is significantly greater than the incidence in the control population. One study6 found as many as four biopsy-proven cases of celiac disease in a single family. Symptoms were often absent or so mild in affected relatives of the proband that these relatives were not aware of any abnormality. The prevalence of celiac disease is approximately 10 percent in first-degree relatives.6

Pathogenesis

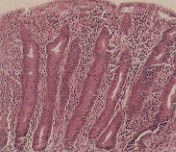

Normally, ingested food does not elicit a local or systemic immune response. Ingestion of protein down-regulates the intestinal immune response to that protein. This phenomenon is known as oral tolerance.7 In patients with celiac disease, the immune system is abnormally activated by gluten, specifically the gliadin portion of wheat protein, and prolamines (insoluble proteins) in rye, barley and oats.8 Thus, celiac disease is a genetic, immunologically mediated, small intestine enteropathy in which mucosal villi are destroyed by cellular and humoral-mediated immunologic reactions to gliadin protein.9 The loss of functioning villi limits the ability of the small intestine to absorb nutrients, thus adversely affecting all systems of the body (Figures 1 and 2). The immunologic response to gluten may also occur secondarily in other bodily tissues, an example being dermatitis herpetiformis.

Studies of patients with celiac disease using molecular techniques demonstrate a strong association with specific HLA class II genotypes. Approximately 95 percent of patients with celiac disease have a particular type of HLA DQ alpha and beta chain encoded by two genes, HLA-DQA1 0501 and HLA-DQB1 0201.10 If people genetically predisposed to celiac disease do not ingest gluten, they have no manifest illness. Delaying ingestion of gluten products through breast feeding or dietary habits may change or delay the onset of disease.11 Viral exposures may trigger an immunologic response in persons genetically susceptible to celiac disease; this occurs with adenovirus type 12, which shares a sequence of eight to 12 amino acids with the toxic gliadin fraction.12

Clinical Presentation

Infancy

During the first year of life, an infant may manifest celiac disease with intermittent vomiting, diarrhea, growth delay and failure to thrive. The incidence of this early classic presentation in infants has decreased. However, to prevent significant growth problems in infants, confirmation of celiac disease is important13 (Figure 3).

Childhood

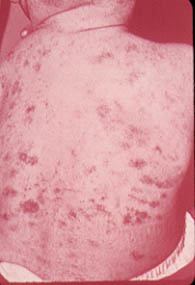

Children with celiac disease may present with short stature, anemia, hepatitis, epilepsy and other extragastrointestinal conditions. With age, these presentations become more subtle. In one study13 of a group of school children screened for IgA antigliadin antibodies, positive titers were found in 19 of the children. Endoscopic biopsies were performed in 18, and villous atrophy was found in 12. None of these children had shown characteristic symptoms of celiac disease. The most frequent of their symptoms were abdominal pain, aphthous stomatitis and atopic dermatitis (Figures 4 and 5).

Young Adults

The initial presentation of celiac disease in patients in their 20s and 30s may be dermatitis herpetiformis. This condition usually appears as clear or blood-tinged vesicles symmetrically distributed over the extensor areas of the elbows, knees, buttocks, shoulders and scalp (Figure 8). Intense pruritus and/or burning sensations in the area occur hours before the onset of the vesicle. Dermatitis herpetiformis flares after consumption of foods containing a high amount of gluten.

Small intestine biopsies from patients with dermatitis herpetiformis reveal features identical to those found in patients with celiac disease.14 In a study15 of 212 patients with dermatitis herpetiformis who were managed over a period of 25 years with a gluten-free diet, several benefits of dietary therapy were found, including (1) the patients' need for medication was reduced or abolished, (2) the enteropathy resolved and (3) patients experienced a feeling of well-being after beginning the diet.

In a study16 of the occurrence of malignancies and the survival of 305 patients with dermatitis herpetiformis from 1970 to 1992, it was indicated that the incidence of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma is significantly increased in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis. The results also confirmed no increase in mortality in patients with dermatitis herpetiformis who are treated with a gluten-free diet.

Celiac disease has not been previously recognized as a cause of alopecia. In a prospective screening,17 254 consecutive outpatients with alopecia areata were tested, using antigliadin and antiendomysial antibodies. Results were positive in three patients and, despite a lack of gastrointestional symptoms, these patients underwent intestinal biopsy. All three were found to to have celiac disease, and treatment with a gluten-free diet was initiated.

When a 14-year-old boy with alopecia universalis complied with the gluten-free diet, all of his hair, eyebrows and eyelashes regenerated.18 In this prospective study, the prevalence of celiac disease associated with alopecia areata was found to be one in 85.

Adults

Malabsorption. The varied signs and symptoms of malabsorption may be caused by celiac disease or many other diseases. Mild malabsorption may be asymptomatic. With its gradual onset, the classic manifestations of flatulence and bulky, greasy and foul-smelling stools may not be recognized by the patient as signs of celiac disease. Malabsorption should be suspected in any patient with weight loss and diarrhea, and the signs and symptoms of specific vitamin or nutritional deficiencies. The latter include visual disturbances, neuropathy, anemia, osteopenic bone disease, tetany, hemorrhagic diathesis or infertility.

In celiac disease, the clinical symptoms are determined by the severity and the proximal-to-distal extent of the intestinal lesions. Symptoms often manifest in childhood and then disappear, only to recur in adulthood. In some patients, the disease presents initially in their 60s and beyond19,20 (Table 1).

| Signs and symptoms | Pathophysiologic mechanism | Laboratory abnormalities |

|---|---|---|

| Gastrointestinal | ||

| Diarrhea | Malabsorption of fat, carbohydrate and protein | Stool weight >200 g |

| Stool weight decreased to normal with fast | ||

| Weight loss | Nutrient malabsorption | Increased stool fat, decreased serum proteins |

| Flatulence, borborygmi, abdominal distention, foul-smelling stools | Bacterial fermentation of malabsorbed carbohydrates and proteins | |

| Increased flatus production | ||

| Bulky, greasy stools | Fat malabsorption | Increased stool fat, low serum carotene level |

| Hematopoietic | ||

| Anemia | Iron, pyridoxine, folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies | Microcytic, macrocytic or dimorphic anemia |

| Hemorrhagic diathesis | Vitamin K deficiency | Prolonged prothrombin time |

| Musculoskeletal | ||

| Bone pain (osteopenic bone disease) | Calcium, vitamin D and protein malabsorption | Hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, increased serum alkaline phosphatase level |

| Tetany | Calcium, magnesium, vitamin D malabsorption | Hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, increased serum alkaline phosphatase level, hypomagnesemia |

| Endocrine | ||

| Amenorrhea, infertility, impotence | Malabsorption with protein-calorie malnutrition | Low serum protein levels; may have abnormalities in gonadotropin secretion |

| Probable vitamin D and calcium deficiencies | Increased alkaline phosphatase, increased serum parathyroid hormone | |

| Skin and mucous membranes | ||

| Cheilosis, glossitis, stomatitis | Iron, riboflavin, niacin, folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies | Low serum iron, folate and vitamin B12 levels |

| Purpura | Vitamin K deficiency | Prolonged prothrombin time |

| Follicular hyperkeratosis | Vitamin A deficiency | Low serum carotene level |

| Scaly dermatitis or acrodermatitis | Zinc and essential fatty acid deficiencies | Low serum or urinary zinc level |

| Hyperpigmented dermatitis | Niacin deficiency | |

| Edema and/or ascites | Protein malabsorption | Hypoalbuminemia |

| Nervous system | ||

| Xerophthalmia and night blindness | Vitamin A deficiency | Decreased serum carotene level |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Vitamin B12 thiamine deficiency | Decreased serum vitamin B12 level |

Anemia. Anemia is a frequent presentation of celiac disease. In one study,21 200 consecutive patients presenting to a hematology clinic were screened for antigliadin and antien-domysial antibodies. Patients with both positive titers underwent intestinal biopsy, and in 10 (5 percent), results were positive for celiac disease. The prevalence increased to 8.5 percent if the patients with macrocytic anemia and the patients with bleeding who responded to iron therapy were excluded. The authors of this study recommend including celiac screening in the diagnostic algorithm of patients with anemia.

In a carefully controlled study,22 it was found that 25 percent of patients with celiac disease and partial villous atrophy had positive fecal occult blood tests, and 54 percent of patients with total villous atrophy had positive fecal occult blood tests. Screening for occult blood in stool is considered primarily a screening for cancer, but celiac disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Osteopenia. Osteopenia may be the initial finding in patients with celiac disease. In a unique study,23 eight asymptomatic first-degree relatives of patients with celiac disease were also found to have celiac disease. All were initially diagnosed by serology, followed by histologic demonstration of villous atrophy. Subsequently, these patients were found to have reduced mineralization of skeleton when evaluated by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry. The study concluded that reduced mineralization occurs in asymptomatic celiac patients, and that early diagnosis and treatment can prevent bone demineralization.

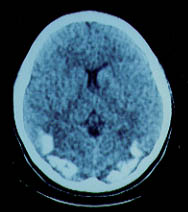

Seizures. There have been numerous reports of children and adults with seizures associated with celiac disease. Studies have provided some insight into this condition. The Institute of Clinical Pediatrics24 evaluated 783 patients referred because of seizures. Serology tests for antigliadin and antiendomysial antibodies were performed in all of these patients. In a cohort of 36 patients who also had clinically evident celiac disease, no further seizures were noted after treatment with a gluten-free diet. In a second group of nine patients, celiac disease was not recognized because of mild or absent symptoms, but the diagnosis was confirmed by jejunal biopsy. Three of these nine patients showed occipital calcifications on brain imaging (Figure 9).

In another study,25 31 patients with epilepsy and cerebral calcifications (a reported complication of celiac disease) underwent blood screening and endoscopy. Of these patients, 24 were diagnosed with celiac disease. The authors of this study found that a gluten-free diet was only beneficial in affecting the clinical course of epilepsy if the diet started soon after the onset of the seizures.

A child with intractable seizures, occipital calcifications and folate deficiency due to celiac disease underwent therapeutic resection of the right occipital lobe and remained seizure-free for four years.26 Pathologic examination of brain tissue revealed a cortical vascular abnormality with patchy pial angiomatosis, fibrosed veins and large, jagged microcalcifications. These abnormalities were similar, although not identical, to those found in patients with Sturge-Weber syndrome.

A review27 of 39 published articles on patients with celiac disease, cerebral calcifications and epilepsy concluded that the exact pathogenic process was unknown. Chronic folic acid deficiency in untreated patients was considered a possible explanation. Mental impairment was extremely variable.

Hepatic Disease. Celiac disease has long been recognized as a cause of chronic hepatic pathology.28 In one report,29 three severely ill patients presented with clinical and laboratory evidence of liver disease but no evidence of viral hepatitis. Each patient had minimal or intermittent gastrointestinal symptoms; liver biopsies showed nonspecific changes or fatty infiltration. Because of the protean nature of the patients' presentations, diagnoses were delayed six months until established by endoscopic duodenal biopsy.

In another study,30 sera were analyzed for gliadin antibodies (IgA and IgG) from 327 consecutive patients with chronic liver disease. Gliadin antibodies were detected in 19 patients; 10 of these patients had biopsies, and a diagnosis of celiac disease was confirmed in five. The authors suggest that celiac disease be considered in cases of chronic “cryptogenic” liver disease.

Associated Diseases

Diabetes Mellitus Type 1

A prospective cohort study31 to determine the prevalence of celiac disease in 47 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus was undertaken at an army medical center. Antiendomysial antibody testing was used for screening; diagnosis required histologic evidence of villous atrophy and cryptic hyperplasia. Three of the 47 patients (6.4 percent) with diabetes also had celiac disease. The authors conclude that celiac disease appears to be more common in patients with type 1 diabetes than in the general U.S. population. In another report,32 diabetes was present in 5.4 percent of celiac patients, compared with only 1.5 percent of control subjects.

Thyroid Disease

An apparent association exists between thyroid disease and celiac disease. In one study,33 83 patients with autoimmune thyroid disorder were screened for celiac disease. Three patients with asymptomatic celiac disease were found and one patient who had previously been diagnosed with celiac disease, giving an overall frequency of 4.8 percent. By contrast, one of 249 age- and sex-matched blood donors was found to have celiac disease.

An epidemiologic study32 looked at 335 patients diagnosed with celiac disease between 1980 and 1990. The associated illnesses of these patients were compared with age- and sex-matched control patients who had various gastrointestinal symptoms. Autoimmune thyroid diseases were found to be increased, occurring in 5.4 percent of the patients with celiac disease.

Down Syndrome

Patients with Down syndrome have an incidence of celiac disease of at least 7 percent.34 Screening for celiac disease in 115 children with Down syndrome using antigliadin, antien-domysial and antireticulin serum antibodies and an intestinal permeability test resulted in a positive diagnosis in eight children. The authors recommend screening all patients with Down syndrome for celiac disease. Table 2 summarizes symptoms, physical findings, and illnesses associated with celiac disease.

| Body system | Presentation | |

|---|---|---|

| General systemic | Adults: lassitude, inanition, depression, fatigue, irritability, general malnutrition with or without weight loss | |

| Children: irritability, fretfulness, emotional withdrawal or excessive dependence, nausea, anorexia, malnutrition with protruberant abdomen, muscle wasting of buttocks, thighs and proximal arms; with or without vomiting and diarrhea | ||

| Skin and mucous membranes | Aphthous stomatitis (recurrent) | |

| Angular cheilitis | ||

| Atopic dermatitis (persistent or recurrent) | ||

| Dermatitis herpetiformis (in 5 percent of patients with celiac disease) | ||

| Alopecia areata (especially alopecia universalis) | ||

| Melanosis (chloasma bronzium) | ||

| Erythema nodosum | ||

| Skeletal system | Osteoporosis/osteopenia (in 100 percent of patients with celiac disease) | |

| Dental enamel defects | ||

| Short stature | ||

| Arthritis or arthralgia (central arthritis-sacroiliitis in 63 percent of patients with celiac disease) | ||

| Bone pain, especially nocturnal | ||

| Hematologic system | Anemia (iron deficiency is the most common cause), folic acid deficiency in 10 to 40 percent of children and 90 percent of adults; B12 deficiency (rare) | |

| Leukopenia, coagulopathy and thrombocytosis. | ||

| Gastrointestinal system | Diarrhea in 60 percent of patients (small intestinal type), early diarrhea occurs with infrequent, large, watery, foul stools; later diarrhea occurs more frequently | |

| Constipation in 20 percent of patients, with occasional obstipation and pseudo-obstruction | ||

| Lactose intolerance in 50 percent of patients with gastrointestinal symptoms | ||

| Anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and bloating | ||

| Pancreatitis, hepatitis, lymphoma | ||

| Immune system | Associated autoimmune diseases: | |

| Diabetes mellitus type 1 | ||

| Thyroid disease | ||

| Sjögren's syndrome | ||

| Collagen disorders | ||

| Rheumatoid arthritis | ||

| Liver disease | ||

| Selective IgA deficiency | ||

| Reproductive system | Delayed puberty | |

| Infertility | ||

| Neurologic system | Seizures, with or without occipital calcification | |

| Unexplained neuropathic illnesses, including ataxia and peripheral neuropathies | ||

| Dementia | ||

| Other associated conditions | Down syndrome | |

| IgA nephropathy | ||

| Fibrosing alveolitis of the lung | ||

| Hyposplenism, with atrophy of the spleen | ||

Diagnosis

Causes of Delay in Diagnosis

Recognizing celiac disease on the basis of the various manifestations of the disorder is difficult. In a study20 of 228 patients with adult-onset celiac disease, it was found that 42 were diagnosed at age 60 or later. Seven patients with dermatitis herpetiformis were excluded, leaving 35 patients in the analysis. Fifteen of the 35 patients had been seen—with unexplained symptoms and abnormal blood tests—for an average of 28 years by their family physicians or in hospital outpatient departments before the diagnosis of celiac disease was made.

A national survey35 of 1,937 members of the Canadian Celiac Association addressed the issue of previous missed diagnosis of celiac disease. Of 686 patients with biopsy-proven celiac disease, 299 (43 percent) had previously been given the following incomplete or missed diagnoses: anemia, 47; stress, 45; nervous condition, 41; irritable bowel syndrome, 34; gastric ulcer, 23; food allergy, 19; colitis, 13; menstrual problems, 13; edema, 9; gallstones, 9; diverticulitis, 6; dermatitis herpetiformis, 4 and other, 36.

Blood Screening Tests

Routine blood tests may be suggestive of celiac disease (Table 3). Blood for specific screening tests should be drawn before the patient is placed on a gluten-free diet. Current screening tests include IgA, IgG antigliadin antibodies and IgA antiendomysial antibody. In a comparative study5 of 3,783 subjects, the combined presence of antiendomysial antibody and antigliadin antibody was predictive of intestinal mucosal atrophy in 99.1 percent of subjects. If both antibody tests were negative, the mucosa was normal in 99.1 percent of subjects. After a gluten-free diet was followed by affected patients, IgA antigliadin antibody levels became undetectable. The authors of this study conclude that antiendomysial antibody screening is an excellent test for the diagnosis and follow-up of celiac disease and for identification of asymptomatic patients.

| Tests | Pathophysiology |

|---|---|

| Alkaline phosphatase level | Because of calcium's essential role in muscle contractility, its blood concentration is carefully regulated. Decreased absorption of calcium causes the parathyroid to activate osteoclasts to maintain normal calcium levels. Osteoclasts secrete alkaline phosphatase. |

| Anemia | Microcytic-hypochromic (sideropenic): lack of response to iron therapy may indicate malabsorption |

| Normocytic-normochromic (lack of iron and folate) | |

| Cholesterol and low-density cholesterol levels | Low, or “too good,” because of lack of absorption and diminished production resulting from liver impairment. (High-density cholesterol is also low, probably because of liver impairment.) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase level | Minimal elevation |

| Plasma protein-albumin level | Borderline low |

In one study,36 102 patients examined for nonspecific abdominal symptoms underwent small intestine biopsy. (Patients with dermatitis herpetiformis were excluded.) In this group, 49 patients were ultimately diagnosed with celiac disease. In these patients, IgA anti-endomysial antibodies had a sensitivity and specificity of 100 percent. Sensitivity of IgG antigliadin antibodies was 73 percent, and specificity was 74 percent. Sensitivity of IgA antigliadin was 82 percent, and specificity was 83 percent. The authors of this study conclude that IgA antiendomysial antibody is the best screening test for celiac disease, except in the case of patients with IgA deficiency.

Pathologic and Clinical Conformation

In 1990, the working group of ESPGAN37 revised criteria for the diagnosis of celiac disease. The group reaffirmed diagnosis with small intestine biopsy demonstrating villous atrophy and by complete resolution of clinical symptoms while on a gluten-free diet. The working group questioned the previous recommendation of follow-up biopsy to confirm villous recovery.

Treatment

Treatment for celiac disease is a strict gluten-free diet. This includes elimination of the storage proteins (prolamines) of wheat, barley, rye and oats.38 It also includes eliminating gluten in over-the-counter medications by carefully checking the labels for ingredients such as hydrolyzed plant and vegetable proteins, modified food starch, cereal solids, and the more obvious oat hull fibers, wheat flour and glutens. Home food preparation requires a strong commitment to exclude glutens.

Major problems arise when patients buy prepared foods or eat in restaurants. Prepared soups, sauces and gravies frequently contain large quantities of gluten. Patients should be instructed to read all labels on packaged foods to help them determine if the product contains gluten. Physicians should encourage patients to join a celiac support group (see patient information handout). Patients with celiac disease should be carefully followed to help ensure dietary compliance and to decrease morbidity from osteoporosis, lymphoma and other illnesses associated with celiac disease.

Final Comment

New data have determined that celiac disease is more common than was previously thought. The diverse secondary clinical manifestations make it an easy diagnosis to miss. Physicians may find themselves unsuccessfully pursuing expensive tests to explain a patient's persistent symptoms or laboratory abnormalities. A high index of suspicion is required to diagnose celiac disease. A physician should consider celiac disease in a patient with a confounding presentation. The proof of the diagnosis is progressive improvement in the patient's symptoms when on an absolutely gluten-free diet. If the diagnosis remains in question, an endoscopic examination should be performed and several biopsy specimens should be taken from the lower duodenum and upper jejunum. It is helpful to have this tissue interpreted by a pathologist familiar with celiac disease. Table 4 lists resources for physicians interested in learning more about celiac disease.

| The Celiac List at St. John's University listserv@maelstrom.stjohns.edu message: GET CELIAC WELCOME |

| Mike Jones: reference file on celiac disease for physicians and patients; material to help inform patients about celiac disease and diet control. mjones@DIGITAL.NET |

| CEL-PRO: discussion group with 2,000 subscribers in 30 nations, for professionals only, with clinical or research interest in celiac disease. To join CEL-PRO, contact <mjones@DIGITAL.NET |