Am Fam Physician. 1998;57(8):1795-1802

See related patient information handout on hyperparathyroidism, written by the authors of this article.

Hyperparathyroidism is a common cause of hypercalcemia. The hypercalcemia usually is discovered during a routine serum chemistry profile. Often, there has been no previous suspicion of this disorder. In most patients initially believed to be asymptomatic, previously unrecognized symptoms resolve with surgical correction of the disorder. The symptoms of hyperparathyroidism are vague and often similar to symptoms of depression, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia or stress reaction. Complications of primary hyperparathyroidism include peptic ulcers, nephrolithiasis, pancreatitis and dehydration. Surgical management is usually indicated. When medical management is used, routine monitoring for clinical deterioration is recommended. Preoperative localization of adenomas with technetium Tc 99m sestamibi scan is possible but may be unnecessary. An experienced surgeon should perform the parathyroidectomy.

During the early 1970s, the advent of multichannel autoanalyzers and the “profiles” they produced appeared to increase the incidence of primary hyperparathyroidism fivefold, but the severity of the condition declined to an “asymptomatic” presentation.1 Investigation of an unexpected elevation in calcium, found incidentally on a serum chemistry profile, was then (and still remains) the usual route to the diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism.2 The incidence of hyperparathyroidism recently has declined.

Pathophysiology

The parathyroid glands are located behind the thyroid gland. Although the number and position can vary, there are usually four parathyroid glands.3

Parathyroid hormone consists of 84 amino acids derived from a prohormone. The effects of parathyroid hormone on serum calcium are mediated by increasing renal tubular resorption of calcium, increasing calcium absorption from the intestines (via vitamin D) and increasing release of calcium from bone. A negative feedback mechanism normally decreases production of parathyroid hormone as the ionized serum calcium level increases.4 Disease states with altered protein binding require a correction factor to determine the ionized calcium level from the total calcium level. A low measured calcium with low albumin may be corrected by adding 0.8 mg per dL (0.2 mmol per L) of calcium for each gram per dL that the albumin is below 4 g per dL (1 mmol per L). Alternatively, the serum ionized calcium level can be measured directly.

In 85 percent of the persons affected, hyperparathyroidism is the result of an adenoma in a single parathyroid gland. Hypertrophy of all four parathyroid glands causes hyperparathyroidism in 15 percent of patients. A very small number of cases of hyperparathyroidism result from parathyroid malignancies.5 In addition, the incidence of hyperparathyroidism is higher in patients with type I and type II multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes, in patients with familial hyperparathyroidism and in patients who received radiation therapy to the head and neck area for benign diseases during childhood.

Secondary hyperparathyroidism occurs when the parathyroid glands are chronically stimulated to release parathyroid hormone. A decrease in circulating calcium is the stimulus for this release. Chronic renal failure, rickets and malabsorption syndromes are the most frequent conditions leading to secondary hyperparathyroidism. In these cases, the elevation of parathyroid hormone is the appropriate response.

In some cases of prolonged secondary hyperparathyroidism, the glands take on an autonomous function manifested by continued high levels of parathyroid hormone despite resolution of the original stimulus. This state is referred to as tertiary hyperparathyroidism.

The incidence of hyperparathyroidism increases with age. In persons over the age of 65 years, hyperparathyroidism occurs in one out of every 1,000 men and in two to three times that number of women.

Diagnosis

Some combination of headaches, fatigue, anorexia, nausea, paresthesias, muscular weakness, pain in the extremities, pain in the abdomen and other such nonspecific symptoms appears to be the most common presentation of primary hyperparathyroidism. The varied symptoms of hyperparathyroidism place it in the differential diagnosis of most chief complaints. Elevated levels of calcium and parathyroid hormone measured by double antibody immunoradiometric assay usually confirm the diagnosis. A scattergram plot (Figure 1) of parathyroid hormone versus calcium may help interpret the results.

Figure 1 also demonstrates that serum calcium levels may be normal in secondary hyperparathyroidism. Nearly all other causes of hypercalcemia suppress the release of parathyroid hormone. Hyperparathyroidism causes a modest increase in levels of chloride and a similar modest decrease in levels of phosphate. Calculation of the ratio of chloride to phosphate amplifies these changes. A ratio above 33 is suggestive of hyperparathyroidism. Radiographs are of limited diagnostic value in the early stages. Normal radiographs do not necessarily mean that bone metabolism is normal. Dual beam radiograph-based photon absorptiometry of the distal forearm can demonstrate a loss of bone mineral density when the patient is presumed to be asymptomatic.

Differential Diagnosis

Table 1 lists some common causes of hypercalcemia.

| Common causes of hypercalcemia |

| Hyperparathyroidism, including ectopic hyperparathyroidism |

| Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy via parathyroid-related protein (especially malignancy of the lung, kidney, ovary, head and neck, and esophagus) |

| Renal failure |

| Malignancy via direct bone destruction (especially myeloma, lymphoma and metastatic breast cancer) |

| Thiazide diuretics |

| Uncommon causes of hypercalcemia |

| Immobilization |

| Lithium use |

| Vitamin D toxicity |

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Milk alkali syndrome |

| Multiple endocrine adenomatosis syndromes |

| Granulomatous diseases, especially sarcoidosis, via increased levels of 1,25(OH)2D3 |

| Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia |

Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy refers to elevated calcium levels associated with secretion of a protein similar to parathyroid hormone, termed parathyroid hormone–related peptide. Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy has been associated with malignancies of the lung, kidney and ovary, and other sites and cell types. Fortunately, the parathyroid hormone assay is not affected by the presence of parathyroid hormone–related peptide. In cases of humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy, the parathyroid hormone level is suppressed.

Granulomatous conditions such as sarcoidosis can cause an elevated serum calcium level that is mediated by an increase in levels of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25(OH)2D3). A trial of systemic glucocorticoid therapy will usually suppress the hypercalcemia of myeloma and other hematologic malignancies and of sarcoid and other granulomatous maladies, but not the hypercalcemia of hyperparathyroidism. However, glucocorticoids do not reliably suppress the hypercalcemia of malignancy from solid tumors and, thus, this test cannot reliably differentiate the hypercalcemia of hyperparathyroidism from that of malignancy.

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia must also be considered in the differential diagnosis of hypercalcemia. This rare, benign, familial condition presents with an elevated serum calcium level and an inappropriately high-normal to high parathyroid hormone level. Low levels of urinary calcium in the patient and in relatives establish this diagnosis.6

Use of thiazide diuretics and lithium occasionally will elevate levels of both parathyroid hormone and calcium. Parathyroid hormone and calcium levels may need to be reassessed after a medication-free period before a diagnosis can confidently be made.

Figure 2 is an algorithm that may be used during the evaluation of patients with hypercalcemia.

Effects of Hyperparathyroidism on Body Systems

Central Nervous System

Mental disorders, especially depression, and central nervous system dysfunction are commonly associated with hypercalcemia and hyperparathyroidism.7 Several suicides have been attributed to hyperparathyroidism.8 Patients (even those originally believed to be asymptomatic) often feel better after removal of a dysfunctional parathyroid gland.

Renal and Genitourinary Systems

Nocturia and polyuria result from the effects of calcium on the renal tubule. Approximately 20 percent of patients with hyperparathyroidism have kidney stones. Conversely, only 2 to 3 percent of patients with kidney stones have hyperparathyroidism. Nephrolithiasis is more common in patients with the slow, insidious form of hyperparathyroidism. The more fulminant “parathyroid storm,” while resulting in higher urinary calcium levels, has such a rapid time course that kidney stones do not have time to develop.

Cardiovascular System

A Swedish study9 following patients with hyperparathyroidism for over 10 years showed that mortality from cardiovascular disease was higher in the study subjects with hyperparathyroidism than in the control population. Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and a decrease in function of the muscles of respiration may account for some of this effect.10 Patients with hyperparathyroidism are more likely than control subjects to have hypertension and congestive heart failure, and are more likely to exhibit changes on electrocardiogram.9 If the induced hypertension is treated with a thiazide diuretic, the calcium level may elevate further and, thus, confound the diagnosis.

Musculoskeletal System

At least in relatively mild cases, the bone loss associated with hyperparathyroidism involves the peripheral skeleton more than the vertebral bodies and affects cortical bone more than cancellous bone. Nonspecific myalgias are the most common musculoskeletal symptoms. The lesions of osteitis fibrosa cystica, previously referred to as brown tumors, mimic malignant lesions and occur in patients with advanced disease.

Gastrointestinal System

Anorexia, constipation and nausea can occur as a result of hyperparathyroidism. Peptic ulcer disease occurs in 15 percent of patients. If patients take antacids (particularly those containing calcium) for ulcer symptoms, they risk aggravating hypercalcemia by adding milk-alkali syndrome (an increased serum calcium level in the face of calcium intake and an alkaline gastric environment) to the malady. The anorexia and nausea added to the dehydrating renal effect of polyuria can deteriorate into a “parathyroid storm” (also referred to as parathyroid poisoning or parathyroid crisis). Pancreatitis is sometimes an additional manifestation of primary hyperparathyroidism. Pancreatitis, often accompanied by hypocalcemia, can be a confusing symptom when considered with an inappropriately high or normal calcium level.

Pregnancy

Maternal hyperparathyroidism can lead to profound hypocalcemia and tetany in the newborn. This may be the first manifestation of maternal hyperparathyroidism.11 Apparently the elevated maternal calcium levels suppress fetal production of parathyroid hormone until delivery occurs. Following delivery, the suppressed neonatal parathyroid hormone and the abrupt halt of maternal calcium produce hypocalcemia.12 The mechanism is analogous to the problem of neonatal hypoglycemia in newborns of mothers with diabetes. Nausea and vomiting suggestive of hyperemesis gravidarum may be the first symptom of hyperparathyroidism in mothers.11 Untreated or medically treated hyperparathyroidism in pregnancy carries a higher rate of morbidity for both fetus and mother. The optimal time for maternal neck exploration is during the second trimester. This timing avoids the period of organogenesis in the first trimester and the risk of preterm labor that is present in the third trimester.

‘Asymptomatic’ Effects

A Finnish study1 found that in 65 percent of “asymptomatic” patients, previously unrecognized symptoms were relieved after parathyroid surgery. This is about the same percentage of symptomatic patients who have resolution of symptoms postoperatively. One example of this phenomenon is the abrupt loss of bone that occasionally occurs in patients who are thought to be very stable over long periods of time. In patients with hyperparathyroidism, asymptomatic does not necessarily mean benign.

Nonsurgical Management

Intravenous hydration is the most critical treatment for a patient with an acute presentation of hyperparathyroidism. The addition of furosemide (Lasix) will increase urinary calcium loss. Administration of pamidronate (Aredia) inhibits bone resorption and lowers serum calcium levels. Other drugs that have been used in the management of acute hyperparathyroidism include calcitonin (Calcimar, Miacalcin), glucocorticoids and mithramycin (Mithracin), although use of the latter agent is limited by its toxicity. Specific dosing schedules may be found in standard references.

Postmenopausal women, the largest group of patients with hyperparathyroidism, present clinicians with the challenge of trying to decrease serum calcium levels while also trying to prevent osteoporosis. In the absence of absolute contraindications, hormone replacement therapy with estrogen is indicated in these women.13 A recent trial14 demonstrated the protective effect of estrogen on bone in women with otherwise untreated hyperparathyroidism.

Destruction of parathyroid glands with alcohol injected under ultrasound guidance has been successful. Multiple injections may be required, and paralysis of the vocal cords, sometimes permanent, has occurred.15 Some radiologists also use embolization to treat parathyroid adenomas invasively.

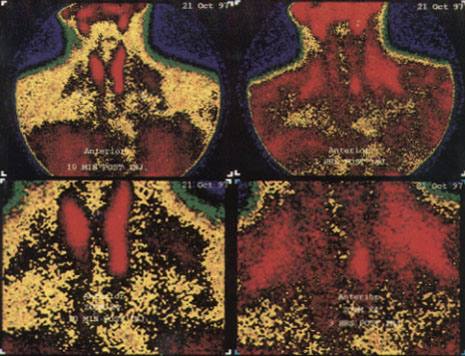

Surgical Management

In some studies, preoperative localization of adenomas decreased the time required for surgery and lowered the incidence of complications.16 Localization of the pathology by computed tomographic (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasonography or radionuclide scans has been used with varying degrees of success. Recently, parathyroid localization with technetium-99m sestamibi has been shown to have high sensitivity and specificity for single adenomas17 (Figure 3). This technique of localization also has resulted in the discovery of parathyroid tumors in the mediastinal area. Larger adenomas are easier to localize than smaller lesions. An externally palpable parathyroid gland should be considered malignant until proved otherwise. Thyroid nodules can be difficult to differentiate from parathyroid pathology on some imaging studies. It has been suggested that the best way to localize an abnormal parathyroid gland is to let a good parathyroid surgeon look for it.17 In fact, this approach is successful about 95 percent of the time.

General indications for surgical management are outlined in Table 2.

| Typical parathyroid-related symptoms involving skeletal, renal or gastrointestinal systems |

| Markedly elevated serum calcium level (1 to 1.6 mg per dL [0.25 to 0.40 mmol per L] above accepted normal range) |

| History of an episode of life-threatening hypercalcemia |

| Reduced creatinine clearance (30% less than that expected) |

| Presence of kidney stones on radiograph |

| Markedly elevated urinary calcium excretion (greater than 400 mg per 24 hours [10 mmol per day]) |

| Substantially reduced bone mass as determined by direct measurement (>2 standard deviations below that expected) |

| Significant neuromuscular or psychologic symptoms without other obvious cause |

| Patient requests surgery |

| Consistent follow-up is unlikely |

| Coexistent illness complicates management |

| Patient is young (<50 years of age) |

Parathyroid surgery has the potential complication of damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Transient hypocalcemia in the immediate postoperative period also is not unusual. Such hypocalcemia responds to calcium supplementation and usually resolves spontaneously. A precipitous drop in the calcium level, accompanied by tetany and seizures, has been called the “hungry bone syndrome”.

Primary hyperparathyroidism recurs in a small percentage of patients after initially successful surgical removal of an adenoma. In one study,1 the recurrence of symptoms was delayed from four to 24 years after the original procedure. It appears that recurrence of primary hyperparathyroidism is considerably less likely when the original finding was a solitary adenoma rather than multiglandular disease.

Recommendations of the National Institutes of Health

In 1990, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Consensus Development Conference on Diagnosis and Management of Asymptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism addressed the diagnosis and management of hyperparathyroidism.18 Table 2 lists the panel's indications for surgery. Candidates for medical management have a mildly elevated serum calcium level, no episodes of life-threatening hypercalcemia and normal renal and bone status. Medical management mandates medical surveillance as indicated in Table 3. The panel's report is not explicit about how often these measurements should be obtained. During medical management, as indicated in Table 4, avoidance of dehydration and immobilization, maintenance of a modest dietary calcium intake and treatment of any hypertension that may develop are advised. Localization studies are not recommended before a first surgical procedure. Contrary to the findings of Lundgren,3 the panel did not find that presurgical localization reduces surgical time or complications.

| Blood pressure |

| Serum calcium |

| Serum creatinine |

| Creatinine clearance |

| Plain radiograph of abdomen |

| Urinary calcium |

| Bone density |

| Avoidance of dehydration |

| Avoidance of immobilization |

| Avoidance of a diet with either high or restricted calcium content |

| Cautious use of thiazide or loop diuretics |

| Treatment of hypertension |

| Replacement of estrogen in postmenopausal women (in absence of contraindication) |

Primary care physicians see many patients with vague and nonspecific symptoms. Hyperparathyroidism should be considered in the differential diagnosis of common conditions such as fibromyalgia syndrome and depression, which also tend to present with multiple, vague symptoms. Calcium status should be determined before an alternate diagnosis is confirmed.