A more recent article chronic asthma treatment is available.

Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(1):89-100

See related patient information handout on managing asthma flare-ups, written by the authors of this article.

Asthma, a common chronic inflammatory disease of the airways, may be classified as mild intermittent or mild, moderate, or severe persistent. Patients with persistent asthma require medications that provide long-term control of their disease and medications that provide quick relief of symptoms. Medications for long-term control of asthma include inhaled corticosteroids, cromolyn, nedocromil, leukotriene modifiers and long-acting bronchodilators. Inhaled corticosteroids remain the most effective anti-inflammatory medications in the treatment of asthma. Quick-relief medications include short-acting beta2 agonists, anticholinergics and systemic corticosteroids. The frequent use of quick-relief medications indicates poor asthma control and the need for larger doses of medications that provide long-term control of asthma. New guidelines from the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program Expert Panel II recommend an aggressive “step-care” approach. In this approach, therapy is instituted at a step higher than the patient's current level of asthma severity, with a gradual “step down” in therapy once control is achieved.

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways that affects 14 million to 15 million persons in the United States. An estimated 4.8 million children have asthma, which makes it the most common chronic disease of childhood.1 With the increased understanding of the role inflammation plays in asthma and the addition of new pharmacologic agents, the management of this disease has improved.

Pathophysiology

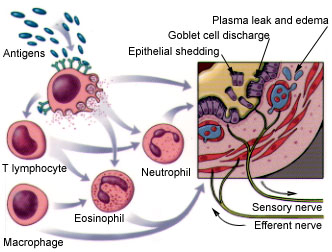

Airway inflammation is the primary problem in asthma. An initial event in asthma appears to be the release of inflammatory mediators (e.g., histamine, tryptase, leukotrienes and prostaglandins) triggered by exposure to allergens, irritants, cold air or exercise. The mediators are released from bronchial mast cells, alveolar macrophages, T lymphocytes and epithelial cells. Some mediators directly cause acute bronchoconstriction, termed the “early-phase asthmatic response.” The inflammatory mediators also direct the activation of eosinophils and neutrophils, and their migration to the airways, where they cause injury. This so-called “late-phase asthmatic response” results in epithelial damage, airway edema, mucus hypersecretion and hyperresponsiveness of bronchial smooth muscle (Figure 1). Varying airflow obstruction leads to recurrent episodes of wheezing, breathlessness, chest tightness and cough.2–4

Diagnosis

Asthma should be considered in patients with a history of recurrent wheezing, cough (particularly if the cough is worse at night), recurrent shortness of breath or chest tightness. The diagnosis of asthma is also suggested if the symptoms worsen with exercise, viral illness, weather changes or exposures to airborne chemicals, dust, tobacco smoke or other allergens, such as animal dander, cockroaches, house dust mites, mold and pollens (Table 1).2

| Potential triggers | Control measures | |

|---|---|---|

| House dust mite | Cover pillows, mattresses and box springs with zippered cases. Wash all bedding in hot water (54.4°C [130°F]) every 10 to 14 days. Use microfilter vacuum bags. Reduce humidity levels with air conditioner and/or dehumidifier. Use air filtering devices, especially in bedroom and family room. Remove bedroom and family room carpeting (small, washable area rugs are an alternative). | |

| Cockroach allergen | Cockroach extermination, preferably by professional exterminators. | |

| Animal allergens | Remove animal from the home, if possible (cat allergens remain in the home for up to six months after the animal is removed). When removal is not possible, confine the animal to carpet-free areas outside the bedroom and use a high-efficiency particulate air filter. | |

| Cat saliva and dander | ||

| Dog allergens | ||

| Rodent urine | ||

| Pollen allergens | Remain indoors as much as possible during times of increased pollen levels. Use home and auto air conditioners (with closed vents) during allergy season. | |

| Trees | ||

| Grasses | ||

| Weeds | ||

| Mold allergens | For outdoor mold, stay indoors and keep windows closed. For indoor mold, use dehumidifier in basement and air conditioners, especially in bedroom and family room. Maintain good ventilation in bathroom and kitchen. | |

| Outdoor or “field” fungi | ||

| Indoor or “storage” fungi | ||

| Nonallergic airborne irritants | Avoid the irritants. | |

| Tobacco smoke | ||

| Smoke from wood-burning stoves, fireplaces and other sources | ||

| Fumes, strong odors | ||

When the diagnosis of asthma is considered, reversible airway obstruction should be documented by spirometry performed before and after the administration of a short-acting bronchodilator. Airway obstruction is indicated by a forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) and a decreased ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FVC) relative to predicted values. Reversibility of obstruction is indicated by an increase in FEV1 after bronchodilator treatment (Table 2).5 In patients with asthma symptoms and normal spirometry, an assessment of the diurnal variation in peak expiratory flow (PEF) is useful in establishing the diagnosis (Table 3).2

| Problem | FEV1 | FVC | FEV1/FVC% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obstructive disease | Decreased | Normal or decreased | Decreased |

| Restrictive disease | Decreased or normal | Decreased | Normal or increased |

| Reversible disease | Increased by 12 to 15 percent after administration of bronchodilator* |

| 1. Instruct patient in peak expiratory flow (PEF) meter technique. |

| 2. Prescribe an inhaled short-acting beta2 agonist and instruct patient in proper use of the medication. |

3. Instruct patient to obtain and record PEF measurements for one to two weeks at the following times:

|

| 4. A 20 percent difference between the morning PEF (generally the lowest PEF of the day) and the midday PEF (generally the highest PEF of the day) suggests that the patient has asthma. |

Classification of Asthma

An expert panel for the National Asthma Education and Prevention Program (NAEPP) recently issued new guidelines that recommend the use of a revised classification system for asthma. Based on these guidelines, asthma is classified as mild intermittent, mild persistent, moderate persistent and severe persistent (Table 4).2 It is important to note that patients at any level of severity may have severe, life-threatening exacerbations.

Pharmacotherapy for Asthma

Medications used in the treatment of asthma may be divided into two categories: long-term control medications that are taken regularly and quick-relief medications that are taken as needed to relieve bronchoconstriction rapidly. (The quick-relief medications are also known as “rescue” medications.) Long-term control medications include anti-inflammatory agents (i.e., corticosteroids, cromolyn sodium [Intal], nedocromil [Tilade] and leukotriene modifiers) and long-acting bronchodilators. Quick-relief medications include short-acting beta2 agonists, anticholinergics and systemic corticosteroids. Any patient with persistent asthma requires treatment with both long-term control and quick-relief medications.

Long-Term Control Medications

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids remain the most potent and effective anti-inflammatory agents available for the management of asthma.6 They are useful in treating all types of persistent asthma in patients of all ages. For long-term use, inhaled steroids are generally preferred over oral steroids because the inhaled agents have fewer systemic side effects. Oral steroid therapy for long-term control is usually used only to treat refractory, severe, persistent asthma. (Short-term oral steroid use is discussed later in this article.)

| Agent* | Dosage | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low dose (per day) | Medium dose (per day) | High dose (per day) | Cost† | |

| Corticosteroids | ||||

| Beclomethasone (Beclovent, Vanceril): 42 and 84 μg per puff | Adults: 4 to 12 puffs at 42 μg per puff or 2 to 6 puffs at 84 μg per puff | Adults: 12 to 20 puffs at 42 μg per puff or 6 to 10 puffs at 84 μg per puff | Adults: more than 20 puffs at 42 μg per puff or more than 10 puffs at 84 μg per puff | 42 μg: $34 (200 puffs) |

| Children: 2 to 8 puffs at 42 μg per puff | Children: 8 to 16 puffs at 42 μg per puff | Children: more than 16 puffs at 42 μg per puff | ||

| Budesonide (Pulmicort): 200 μg per puff | Adults: 1 or 2 puffs | Adults: 2 or 3 puffs | Adults: more than 3 puffs | $111 (200 puffs) |

| Children: 1 puff | Children: 1 or 2 puffs | Children: more than 2 puffs | ||

| Flunisolide (AeroBid): 250 μg per puff | Adults: 2 to 4 puffs | Adults: 4 to 8 puffs | Adults: more than 8 puffs | $54 (100 puffs) |

| Children: 2 or 3 puffs | Children: 4 or 5 puffs | Children: more than 5 puffs | ||

| Fluticasone (Flovent): 44 μg, 110 μg and 220 μg per puff | Adults: 2 to 6 puffs at 44 μg per puff or 2 puffs at 110 μg per puff | Adults: 2 to 6 puffs at 110 μg per puff | Adults: more than 6 puffs at 110 μg per puff or more than 3 puffs at 220 μg per puff | 44 μg: $44 (120 puffs) |

| Children: 4 to 10 puffs at 44 μg per puff or 2 to 4 puffs at 110 μg per puff | 110 μg: $50 (120 puffs) | |||

| Children: 2 to 4 puffs at 44 μg per puff | Children: more than 4 puffs at 110 μg per puff | 220 μg: $72 (120 puffs) | ||

| Triamcinolone acetonide (Azmacort): 100 μg per puff | Adults: 4 to 10 puffs | Adults: 10 to 20 puffs | Adults: more than 20 puffs | $45 (240 puffs) |

| Children: 4 to 8 puffs | Children: 8 to 12 puffs | Children: more than 12 puffs | ||

| Mast cell stabilizers | ||||

| Cromolyn sodium MDI (Intal), 800 mg per puff; nebulizer, 20 mg per 2-mL ampule | Adults: 6 puffs or 3 ampules in three divided doses | Adults: 9 to 12 puffs in three divided doses | Adults: 16 puffs in three divided doses or 4 ampules in four divided doses | $41 (112 sprays, 8.1 g) |

| Children: 3 puffs or 3 ampules in three divided doses | Children: 6 puffs in three divided doses | $66 (200 sprays, 14.2 g) | ||

| Children: 8 puffs or 4 ampules in four divided doses | ||||

| $51 (60 ampules) | ||||

| $95 (120 ampules) | ||||

| Nedocromil (Tilade), 1.75 mg per puff | Adults: 4 to 6 puffs in two to three divided doses | Adults: 9 to 12 puffs in two to three divided doses | Adults: 16 puffs in four divided doses | $28 (112 puffs) |

| Children: 2 to 3 puffs in two to three divided doses | Children: 4 to 6 puffs in two to three divided doses | Children: 8 puffs in four divided doses | ||

Common side effects include cough, dysphonia, throat irritation and oropharyngeal candidiasis. The likelihood of local side effects, especially candidiasis, can be reduced if patients use a spacer, rinse their mouth after each use and use the inhaled steroids less frequently (twice daily rather than four times daily). Higher dosages may be associated with systemic adverse effects, including adrenal suppression, osteoporosis and growth delay in children.7,8

Cromolyn Sodium and Nedocromil

Cromolyn and nedocromil are very safe agents with a mild to moderate anti-inflammatory effect. Both drugs inhibit the early-and late-phase asthmatic response to allergens and exercise. Nedocromil appears to be more effective than cromolyn in inhibiting bronchospasm induced by exercise, cold air and provocative testing.9 Because of their excellent safety profiles, cromolyn and nedocromil are good initial long-term control medications in children and pregnant women with mild persistent asthma.

Cromolyn is available in a metered-dose inhaler (MDI), in capsules for oral inhalation and in a nebulizer solution. The usual dosages for adults are two to four puffs or one ampule of nebulizer solution three or four times daily; for children, one or two puffs or one ampule three or four times daily.

Nedocromil is available only in an MDI. For adults, the dosage is two to four puffs two to four times daily; for children, one to two puffs two to four times daily. Four weeks of continued therapy may be required before the optimal effects of these drugs are achieved.

Salmeterol and Extended-Release Albuterol

Salmeterol (Serevent) is a long-acting beta2 agonist. Its mechanism of action and side effect profile are similar to those of other beta2 agonists.12 Unlike the short-acting agents, salmeterol is not intended for use as a quick-relief agent. It should not be used as a single agent for long-term control but instead should be used in combination with inhaled corticosteroids or other anti-inflammatory agents. Salmeterol is useful in the management of nocturnal and exercise-induced asthma. The drug is administered in an MDI in a dosage of two puffs every 12 hours. The inhalation powder formulation, salmeterol xinafoate (Serevent Diskus), is administered in a dosage of one puff every 12 hours. Several controlled studies13,14 have found that adding salmeterol to inhaled beclomethasone dipropionate produces greater improvement in asthma symptoms and less use of rescue medications than doubling the dosage of inhaled beclomethasone.

Albuterol (Proventil Repetabs, Volmax) is available as an oral extended-release tablet for the long-term control of asthma. Like salmeterol, this long-acting beta2 agonist is not intended to be used as a rescue medication. It is an alternative to sustained-release theophylline or inhaled salmeterol, especially in patients who have nocturnal asthma despite treatment with high-dose anti-inflammatory agents. Albuterol is available in 4- and 8-mg tablets. Doses are taken every 12 hours.

Theophylline

Theophylline, once the mainstay of asthma treatment, is now considered a second- or third-line agent because of its adverse effect profile and potential interactions with many drugs. Furthermore, serum theophylline levels have to be monitored during treatment. In addition to its well-known bronchodilator effects, theophylline also has anti-inflammatory activity.15

Currently, theophylline therapy is generally reserved for use in patients who exhibit nocturnal asthma symptoms that are not controlled with high-dose anti-inflammatory medications. These patients may benefit from the administration of a sustained-action theophylline preparation in the evening, with the drug titrated to a serum concentration ranging from 5 to 15 μg per mL.2

Zafirlukast and Zileuton

The leukotrienes are potent inflammatory mediators in asthma and contribute to increased mucus production, bronchoconstriction and eosinophil infiltration. These compounds are produced via the lipoxygenase pathway by mast cells, eosinophils and alveolar macrophages. Zafirlukast (Accolate) and Zileuton (Zyflo) are two new drugs that antagonize the action of leukotrienes at their receptor (zafirlukast) or inhibit the lipoxygenase pathway (zileuton). Both drugs are approved for the management of chronic asthma in adults and in children older than 12 years16,17 (Table 6).

| Points of comparison | Zafirlukast (Accolate) | Zileuton (Zyflo) |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of action | Blocks the cysteinyl leukotrienes LTD4 and LTE4 at the CsyLT1 receptor | Selectively and reversibly inhibits the 5-lipoxygenase pathway |

| Adverse effects | Generally well tolerated | Generally well tolerated |

| Side effects include headache, infection, nausea, diarrhea | Side effects include dyspepsia, headache, infections, asthma exacerbations | |

| Elevated liver transaminase levels (usually transient; however, liver function tests should be performed monthly for the first three months of therapy and then every two to three months for the first year of treatment) | ||

| Drug interactions | Interacts with drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes 3A4 (e.g., phenytoin [Dilantin], carbamazepine [Tegretol]) and 2C9 (e.g., cisapride [Propulsid], astemizole [Hismanal], dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers) | May interact with drugs metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes 1A2, 3A4 and 2C9 Reported interactions with theophylline, warfarin and propranolol (Inderal) |

| Increases the effect of warfarin (Coumadin) | ||

| Plasma level decreased by erythromycin and theophylline | ||

| Plasma level raised by aspirin | ||

| Contraindications | Breast feeding | Active liver disease |

| Breast feeding | ||

| Precautions | Should be used with caution in elderly patients and patients with hepatic disease | |

| Use in pregnancy | Category B | Not recommended |

| Dosage | 20 mg twice daily, taken one hour before or two hours after meals | 600 mg orally, taken four times daily with or without food |

| Cost* | $56 | $83 |

Zafirlukast blocks the cysteinyl leukotrienes (LTD4 and LTE4) at the CysLT1 receptor. This drug decreases bronchoconstriction, vascular permeability and mucus production; it has also been found to improve asthma symptoms and reduce the use of beta agonists.16 Zafirlukast is generally well tolerated, but headache, diarrhea, nausea and infections may occur.

Zileuton selectively and reversibly inhibits the 5-lipoxygenase pathway, preventing the formation of cysteinyl leukotrienes. Therapy with this agent has improved patient symptom scores and pulmonary function tests, reduced beta-agonist and inhaled corticosteroid use, and reduced asthma exacerbations requiring corticosteroid therapy. In addition, zileuton therapy may improve quality of life in patients with asthma.17

Although zileuton is generally well tolerated, it has the potential to elevate liver transaminase levels. Consequently, liver function should be tested monthly for the first three months of zileuton therapy. The tests should then be repeated every two or three months for the first year of treatment. Zileuton therapy is contraindicated in patients with active liver disease. Other reported side effects include dyspepsia, headache, infections and asthma exacerbations.

Both zafirlukast and zileuton have numerous drug interactions. Furthermore, these drugs have only been studied in patients with mild to moderate asthma. The 1997 NAEPP report suggests that these agents may be an alternative long-term medication in patients older than 12 years with mild persistent asthma (step 2 therapy), but that further clinical experience and study are needed to establish their role in step therapy.2

Quick-Relief Medications

Short-Acting Beta2 Agonists

Short-acting inhaled beta2 agonists are the agents of choice for relieving bronchospasm and preventing exercise-induced bronchospasm. Selective beta2 agonists, including albuterol, bitolterol (Tornalate), metaproterenol (Alupent), pirbuterol (Maxair) and terbutaline (Brethaire), are preferred to nonselective beta agonists, such as epinephrine, ephedrine and isoproterenol (Isuprel), because the selective agents have fewer cardiovascular side effects and a longer duration of action. Inhaled beta2 agonists have a rapid onset of action (i.e., less than five minutes). Peak bronchodilation occurs within 30 to 60 minutes of administration, and the duration of action is three to eight hours.

Several studies18,19 have suggested that chronic daily use of short-acting beta2 agonists may lead to worsening asthma control and decreased pulmonary function, particularly in moderate to severe asthma. Other studies20–22 have failed to demonstrate worsening asthma control but have shown no significant benefit from the regular daily use of beta2 agonists. In light of current information, regularly scheduled daily use of short-acting beta2 agonists is not generally recommended. The frequent use of quick-relief medication (e.g., more than one canister per month) indicates poor asthma control and the need for increased dosages of long-term control medications.

Systemic Corticosteroids

Short-term systemic corticosteroid therapy is useful for gaining initial control of asthma and for treating moderate to severe asthma exacerbations.23 The intravenous administration of systemic corticosteroids offers no advantage over oral administration when gastrointestinal absorption is not impaired. The recommended outpatient “burst” therapy for adults is prednisone, prednisolone or methylprednisolone in a dosage of 40 to 60 mg per day taken as one or two daily doses; for children, 1 to 2 mg per kg per day to a maximum dosage of 60 mg per day. Therapy is continued for three to 10 days or until symptoms resolve and the patient's PEF improves to 80 percent of his or her personal best. The oral steroid dosage does not have to be tapered after short-course “burst” therapy if the patient is receiving inhaled steroid maintenance therapy.2

Anticholinergics

Ipratropium (Atrovent) is a quaternary atropine derivative that inhibits vagal-mediated bronchoconstriction. Although this drug has not been proved to be effective for long-term asthma management, it may be useful as an adjunct to inhaled beta2 agonists in patients who have severe asthma exacerbations or who cannot tolerate beta2 agonists. Ipratropium has few side effects, but inadvertent eye contact can cause mydriasis.

Approach to Therapy

The 1997 NAEPP report recommends a “step care” approach to asthma therapy (Table 7).2 The report discusses two appropriate approaches to initiating therapy for asthma. One approach is to start therapy at the level consistent with the severity of the patient's disease and increase treatment in steps if control is not obtained. A second and more aggressive approach is to initiate therapy at a step higher than the patient's current level of disease severity and gradually “step down” once control is obtained. No studies have directly compared the two approaches. The NAEPP report recommends the second approach because some evidence suggests that initial aggressive treatment may yield greater clinical benefit.24,25 Because asthma is a highly variable disease, the physician needs to individualize treatment strategies. If initial therapy does not provide good control within one month, the treatment plan and even the diagnosis should be reevaluated.

Regular follow-up visits (at one- to six-month intervals) are necessary to ensure that good control is maintained and to evaluate the need for a “step up” or “step down” in therapy. The patient should be carefully questioned about symptoms (cough, breathlessness, nocturnal symptoms, limitation in any activity) and how often quick-relief medication is used. Daily home peak flow monitoring is advised for the patient with moderate or severe persistent asthma and whenever exacerbations occur. Peak flow measurements at office visits can be useful. Spirometry should be performed every one to two years to assess the maintenance of airway function.

Once asthma is well controlled, a step down in therapy is appropriate. Generally, the last medication added to the regimen is the first medication withdrawn. The dosage of inhaled corticosteroids may be decreased by 25 percent every two to three months to the lowest possible dosage needed to maintain control.

Adequate asthma control may not be achieved for various reasons (Table 8).2 The physician needs to be aware of the factors that can affect a patient's ability to control asthma symptoms. If significant exacerbations continue to occur despite efforts to control symptoms, the patient may need to be referred to an asthma specialist (Table 9).2 Children younger than five years who have moderate or severe persistent asthma also may require referral to an asthma specialist.

| Problems with patient adherence to treatment plan |

| Problems with patient technique in using medications |

| Coexisting conditions (e.g., sinusitis, allergen or irritant exposure, gastroesophageal reflux) |

| Psychosocial or family barriers |

| Need for temporary increase in anti-inflammatory medication (e.g., short course of a corticosteroid) |

| Patient in whom good asthma control has been difficult to achieve |

| Patient with severe persistent asthma (step 4) |

| Patient under five years of age with moderate or severe persistent asthma (step 3 or 4) |

| Patient who has a life-threatening exacerbation |

At each follow-up visit, the patient should receive patient education on such subjects as adhering to medication regimens, using an inhaler and PEF meter, and controlling exposures to asthma triggers. Teaching patients self-management strategies (e.g., how to treat exacerbations, when to increase the frequency of peak flow monitoring, when to contact the physician) is vital to achieving good asthma control (Figure 2). Giving the patient a written self-management plan can improve both compliance and satisfaction.26

Final Comment

Asthma and its management still pose a challenge. However, recent advances in our understanding of the pathophysiology, diagnosis and monitoring of asthma can help physicians optimize treatment strategies. Contemporary treatment guidelines emphasize an aggressive approach, with the prompt and liberal use of anti-inflammatory medication to achieve long-term control of this inflammatory disease. It is increasingly recognized that successful asthma treatment requires a commitment from both patient and physician. Patient education can empower persons with asthma to begin guided self-management of their disease. Such shared responsibility will help to ensure a favorable clinical outcome and an enhanced quality of life.