Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(6):1514-1518

Adult circumcision can be performed under local or regional anesthesia. Medical indications for this procedure include phimosis, paraphimosis, recurrent balanitis and posthitis (inflammation of the prepuce). Nonmedical reasons may be social, cultural, personal or religious. The procedure is commonly performed using either the dorsal slit or the sleeve technique. The dorsal slit is especially useful in patients who have phimosis. The sleeve technique may provide better control of bleeding in patients with large subcutaneous veins. A dorsal penile nerve block, with or without a circumferential penile block, provides adequate anesthesia. Informed consent must be obtained. Possible complications of adult circumcision include infection, bleeding, poor cosmetic results and a change in sensation during intercourse.

Circumcision is performed on an estimated one out of six male newborns worldwide.1 Over 60 percent of male newborns were circumcised in the United States in 1992.2 Circumcision in adults is performed much less often; however, accurate statistics are not available. Adult patients often have a medical indication for the procedure, but circumcision may also be done for social or purely personal reasons. Adult circumcision is usually performed in the outpatient setting by urologists. However, family physicians who practice in isolated or rural areas and who are adequately trained may also offer this procedure. All family physicians should be prepared to advise their patients about the indications for adult circumcision and, if necessary, make appropriate referrals for the procedure.

Indications and Contraindications

Although there are numerous medical indications for adult circumcision, none of them is very common.3 The most frequent indication is phimosis, a tightness of the prepuce that prevents its retraction over the glans.4 A patient may also complain of pain with erection or during intercourse. Paraphimosis, the unreplaceable retraction of a narrow foreskin that causes a painful swelling of the glans, is the second most common indication for adult circumcision. Acute paraphimosis is a urologic emergency requiring reduction of the foreskin through surgical or nonsurgical methods. Recurrent balanitis and posthitis (inflammation of the prepuce), preputial neoplasms, excessive prepuce redundancy and tears in the frenulum are also medical indications for adult circumcision.5

Patients may have social, religious or personal reasons for requesting a circumcision.6 It is important to explore these reasons with the patient to ensure that he has a thorough understanding of the risks and benefits of circumcision and alternatives to the procedure.

There are no specific contraindications to adult circumcision in the literature; however, patients with active infection, possible squamous cell carcinoma of the penis or anatomic abnormalities of the external genitalia should be referred for a urologic consultation.

Informed Consent

It is important to provide the patient with adequate information about the procedure ahead of time. Specifically, the patient should be told about the risks of bleeding, hematoma formation, infection, inadvertent damage to the glans, removal of too much or too little skin, aesthetically unpleasing results and a change of sensation during intercourse. The patient should also be informed that, during the postoperative period, erections can cause pain and disruption of the suture line that may require replacement of the sutures. Full recovery following circumcision generally requires four to six weeks of abstinence from all genital stimulation and sexual activity.

The patient should also be reminded about the benefits of circumcision. If he has the procedure, hygiene will be simpler and may result in fewer local infections, resolution of phimosis and paraphimosis, and less risk of frenular tears and bleeding during intercourse.

Alternatively, if the patient elects not to have the procedure, he should be treated with conservative measures for these conditions (e.g., either oral or topical antibiotics, training in meticulous hygiene for patients with balanitis). Patients having a circumcision for recurrent balanitis should be free from infection before the procedure.

Preparation of the surgical site includes a thorough surgical scrub of the genital area with a povidone-iodine preparation. Shaving and clipping of the pubic hair should be avoided to minimize the possibility of infection. Sterile draping of the area should be used to identify the surgical field. An electrocautery unit should be available to provide hemostasis.

Anesthesia

Anesthesia can be accomplished by administering a dorsal penile nerve block, with or without a ring block.7 The penis is innervated by the left and right dorsal nerves; these are branches of the pudendal nerves.8 The dorsal penile nerve is blocked by injecting a local anesthetic solution deep to Buck's fascia where the nerves emerge from under the pubic bone. The patient is then placed in the supine position. After preparation of the skin, two injection sites are identified over the inferior edge of the pubic bone at approximately 10 o'clock and 2 o'clock relative to the base of the penis. A 27-gauge, 1.5-in needle is inserted, directed ventrally, until the pubic bone is contacted. The needle is “walked” caudad off the pubis and through Buck's fascia. After aspiration, 5 mL of local anesthetic is injected at each site. A mixture of equal volumes of 0.5 percent bupivacaine (Marcaine) and 1 or 2 percent lidocaine (Xylocaine) without epinephrine provides rapid onset of anesthesia of suitable duration for circumcision.

As an option, to guarantee adequate anesthesia to the ventral surface and frenulum, a ring block can also be performed. A ring block is a circumferential subcutaneous injection at the base of the penile shaft using a 26- or 27-gauge needle and approximately 10 mL of the anesthetic solution mentioned previously. If the ring block is used in addition to the dorsal nerve block, lidocaine toxicity can be a concern, since a total of 200 mg might be used if 10 mL of 2 percent lidocaine is administered. According to the 1998 Physicians' Desk Reference, the maximum recommended dose of lidocaine without epinephrine is 4.5 mg per kg or approximately 300 mg, although for safety's sake, 200 mg is a better maximum total dose.9

Potential complications are rare and include hematoma formation and intravascular injection of local anesthetic.10 Use of an anxiolytic agent may also be considered. Diazepam (Valium), 5 mg given orally one hour before the procedure, is effective. A eutectic mixture of local anesthetics (e.g., EMLA cream) applied to the skin at the base of the penis 30 to 60 minutes before the injections may decrease the pain associated with the needle sticks.

Dorsal Slit Technique

This technique is preferred for use in patients with phimosis or paraphimosis. In the patient presenting with acute paraphimosis, gentle, steady pressure on the prepuce decreases the swelling. The physician may then reduce the paraphimosis by pushing on the glans with the thumbs and pulling on the foreskin with the fingers.11 If this step is unsuccessful, the dorsal slit can be performed to relieve the pain, and the remainder of the circumcision can be performed at a later time.

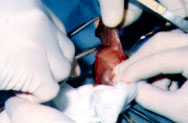

To perform the dorsal slit, the physician needs to identify the corona of the glans and determine the extent of the dorsal slit. This is the most important step in removing the correct amount of prepuce. The slit should extend from the meatal opening 75 percent of the distance to the corona. Counter-traction on the edges of the foreskin while the physician makes the slit with scissors is helpful (Figure 1). The preputial skin should then be held perpendicular from the shaft of the penis and excised at its base with scissors (Figure 2). Large superficial veins are then ligated.

The frenulum is reapproximated first, as it can be a site of problematic bleeding. We prefer to use a subcutaneous “U” stitch for good cosmesis and to help avoid bleeding (Figure 3). The cut edges of the foreskin are closed with multiple simple interrupted stitches using 4-0 or 5-0 absorbable sutures (chromic: Dexon or Vicryl) spaced evenly every 4 to 7 mm (Figure 4). Excess bleeding is controlled with direct pressure and electrocautery. A sterile dressing of petroleum gauze can then be applied over the sutures.

Sleeve Technique

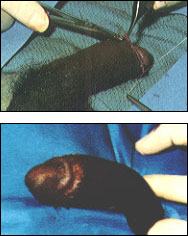

The sleeve resection technique is adaptable for use in both children and adults. In adults, the dorsal penile block, as described previously, is adequate for anesthesia. A skin marker is used to delineate the incisions (Figure 5). The external preputial incision is outlined over the corona and the “V” of the frenulum on the ventral side. The internal preputial incision is marked approximately 1 cm proximal to the coronal sulcus. It is important to apply gentle pressure on the prepubic fat pad at the base of the penis while making the initial outlines so the correct amount of skin will be removed.

The external preputial incision should be made using a scalpel and continued to Buck's fascia. After retracting the foreskin, a second incision should be made in the inner prepuce. This internal incision should be carried straight across the frenulum, as this area tends to retract distally, forming an inverted “V.” A “sleeve” now exists between the two incisions (Figure 6). Hemostats should be placed dorsally for traction. Subcutaneous attachments are then separated between Buck's fascia and the prepuce. The sleeve should then be excised with electrocautery (Figure 7), and excess bleeding should be controlled by ligature or electrocautery. The frenulum is then reapproximated initially with the “U” stitch (Figure 3). Four quadrant sutures should be placed on the dorsum and both sides, and the remaining interrupted sutures should be placed at 4- to 7-mm intervals (Figure 8). Excess bleeding may be controlled with direct pressure and electrocautery. A sterile dressing of petroleum gauze can then be applied over the sutures.

Complications

As with any surgical procedure, bleeding and infection are probably the most common complications of circumcision in adult patients; however, accurate statistics are not available.3 Other complications include hematoma formation, diffuse swelling, pain from inadequate anesthesia, poor cosmesis, tearing of the sutures due to erection before healing is complete and anesthetic complications. Some patients may also note an unpleasant heightened sensitivity during intercourse. Infection can be treated with local or parenteral antibiotics, depending on the severity of the infection. Bleeding can be controlled with pressure, an absorbable gelatin sponge product (i.e., Gelfoam), electrocautery or ligatures. None of these techniques can be preferentially recommended based on differences in complication rate or severity.

Postoperative Care

While many physicians use no dressing at all following adult circumcision, either petroleum jelly and sterile gauze or Xeroform petrolatum gauze can be wrapped circumferentially around the sutured area, followed by sterile gauze and lightly wrapped with self-adherent stretch gauze (Cobain). The dressing should be removed 24 to 48 hours after surgery, after making sure that there is no bleeding or oozing. At this point, no further dressing is necessary, and the patient should be instructed to wear loose-fitting briefs. The patient should also be advised to gently wash the wound daily for the next five to seven days; after that, he may shower regularly. Intercourse and masturbation should be avoided for four to six weeks after the procedure to prevent breakdown of the wound. One ampule of inhaled amyl nitrate can be used as abortive therapy for erections that occur during the recovery period.