Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(8):2189-2194

See related patient information handout on male pattern baldness, written by the authors of this article.

Two drugs are available for the treatment of balding in men. Minoxidil, a topical product, is available without a prescription in two strengths. Finasteride is a prescription drug taken orally once daily. Both agents are modestly effective in maintaining (and sometimes regrowing) hair that is lost as a result of androgenic alopecia. The vertex of the scalp is the area that is most likely to respond to treatment, with little or no hair regrowth occurring on the anterior scalp or at the hairline. Side effects of these medications are minimal, making them suitable treatments for this benign but psychologically disruptive condition.

Hair plays a large role in defining one's self-image. From the “snake oils” of the past to high-tech microsurgical hair plugs, men have been willing to try almost anything and to spend large amounts of money in search of a cure for male pattern baldness.

Minoxidil (Rogaine) and finasteride (Propecia) are labeled for the treatment of male pattern baldness. Annual sales of minoxidil 2 percent solution have exceeded $162 million per year since the drug became available without prescription in 1996.1 In total, an estimated $900 million is spent each year on efforts to regrow hair.1 Clearly, a large population of men eagerly awaits remedies for male pattern baldness.

Background

Hair growth s divided into three phases: anagen, catagen and telogen. Unlike hair follicles of other animals, the hair follicles of humans are not in the same cycle at the same time; each follicle has its own schedule. As a result, humans do not shed seasonally but continually lose and regrow hair.

As male pattern baldness develops, the hairs in the affected areas of the scalp become shorter, finer and less pigmented with successive growth cycles. This androgenic alopecia seems to be associated with the presence of dihydroxytestosterone (DHT), a metabolite of testosterone. Eunuchs, who have low levels of testosterone, do not lose scalp hair. In addition, men with a genetic deficiency of 5α-reductase, the enzyme that converts testosterone to DHT, do not suffer male pattern baldness.

Finasteride is a competitive inhibitor of type II 5α-reductase and can lower DHT levels in tissue. In men undergoing hair transplantation, treatment with 5 mg of finasteride per day lowers the amount of DHT in bald scalp to levels comparable to baseline levels in hair-containing scalp.2 The mechanism of action of minoxidil appears to be a direct effect on the follicles, increasing proliferation and differentiation of epithelial cells in the hair shaft.3

Diagnosis

Since up to two thirds of men experience androgenic alopecia, male pattern baldness is considered a normal variant rather than a disease. Although devoid of serious health aspects, patient concerns about balding should be taken seriously since one half of balding patients have psychologic sequelae.4

Although androgenic alopecia is the most common cause of male pattern baldness, pathologic causes of alopecia must also be considered in the evaluation of hair loss in men. Alopecia typically is divided into scarring and nonscarring types (Table 1). Scarring alopecia is typically seen in patients with infectious or connective tissue diseases. Androgenic alopecia is a nonscarring variety. Table 1 lists other causes of nonscarring alopecia.5

| Nonscarring alopecia |

| Androgenic alopecia |

| Telogen effluvium |

| Anagen effluvium |

| Trichotillomania |

| Traction alopecia |

| Alopecia areata |

| Secondary syphilis |

| Congenital hair shaft disorders |

| Scarring alopecia |

| Inflammatory dermatoses (e.g., connective tissue diseases, such as lupus erythematosus) |

| Infection |

| Physical and chemical agents |

| Neoplasms |

| Congenital defects |

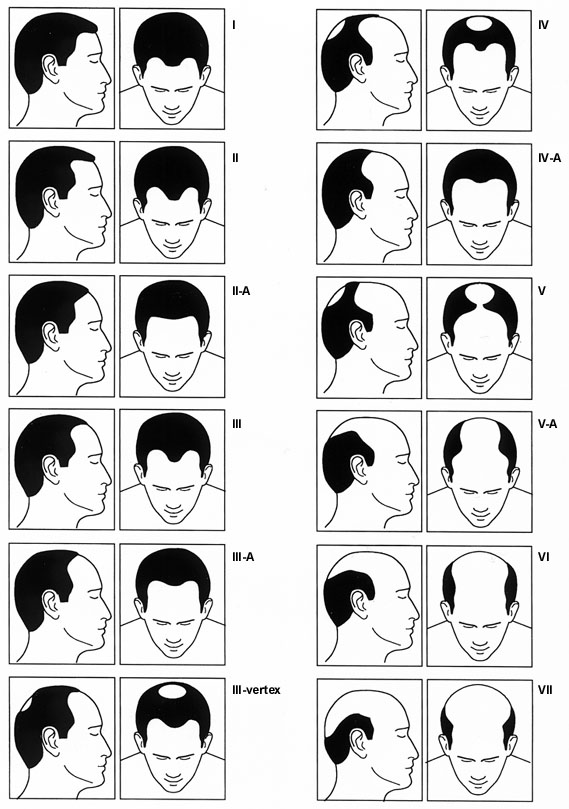

The patient's history plays an important role in establishing the differential diagnosis. Key elements of the history include family history, medications, concomitant medical illness, stresses, and the pattern and speed of progression of hair loss. A family history and a gradual progression of hair loss in the characteristic “M” pattern described by Hamilton (Figure 1) suggest male pattern baldness. Patchy hair loss may be associated with conditions such as tinea capitis, lupus erythematosus and immune-mediated alopecia areata. A history of abrupt hair loss following a significant stress is indicative of telogen effluvium. Definitive diagnosis, particularly in cases of scarring alopecia or unusual patterns of hair loss, requires biopsy before treatment is initiated.

Topical Minoxidil and Oral Finasteride

Concoctions purported to regrow hair have been sold to an uncritical public for generations. Most of these tonics have had a temporary effect or no effect at all. In 1989, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued guidelines for the use of products for hair growth or hair loss prevention, which cleared the shelves of ineffective nonprescription products.

In 1980, the first case report was published of hair growth related to the use of oral minoxidil, an agent marketed for the treatment of severe hypertension. Finasteride initially was marketed for the treatment of benign prostatic hypertrophy. The action of the latter agent lowers DHT levels by inhibiting 5α-reductase. Since DHT had a known role in androgenic hair loss, the use of finasteride in treating hair loss was pursued early in the development of this agent.

Effectiveness

No studies have directly compared minoxidil with finasteride in balding patients, and only a single case report describing their use in combination is available.6 The studies that resulted in the labeling of these agents have been published only in abstract form.

Minoxidil has been available for over 10 years at a 2 percent concentration, and a new, 5 percent formulation (Rogaine Extra Strength) is now sold without prescription. Finasteride, originally marketed as a 5-mg tablet for the treatment of symptoms of benign prostatic hypertrophy, is now available as a 1-mg tablet for the treatment of hair loss in men.

Studies published in the late 1980s showed that minoxidil 2 percent topical solution could grow hair of moderate to dense thickness in about 50 percent of patients.7 Although few mature, terminal hairs were regrown, the number of fine, nonpigmented or vellus hairs was less, while the number of other hairs increased. Patients deemed this growth cosmetically pleasing, and these findings led researchers to conclude that minoxidil is effective in slowing or preventing hair loss.

These studies identified the ideal candidate for therapy as a man who has been bald for less than five years and whose bald area is less than 10 cm (4 in) in diameter and located on the vertex. Minoxidil was not useful for treatment of frontal hair loss. Men who stopped using minoxidil showed a rapid loss of the hair that was gained during therapy. By three months after discontinuation of therapy, hair counts were at or below baseline hair counts.

One study questioned participants who had used the product for 2.5 years. The study results indicated that 32 percent of these men had hair that grew long enough to be cut, and 36 percent felt that it was worth the time and money to continue treatment with the product.8

Two studies have compared the new, higher strength minoxidil with the 2 percent solution.9,10 In one study, men used one of the two solutions for almost two years. The outcome measured in this study was hair mass (the weight of the hair taken from a standard, defined area of the scalp). This measurement accounts for both the number of hairs and their thickness. The higher strength led to a greater hair mass, with the difference being most marked early in the study. After five months of treatment, the group treated with the 5 percent solution had a 55 percent increase in total hair mass over baseline, compared with a 25 percent increase for the 2 percent group. After two years of treatment, hair mass was down to 25 percent over baseline in the 5 percent group and 15 percent above baseline in the 2 percent group.9

In the second study, 5 percent minoxidil produced significantly more nonvellus hair by hair count. Patients using the higher strength also were more likely to notice a change in hair coverage of the scalp and in their assessment of benefit of treatment.10

The effectiveness of finasteride has been evaluated in three studies involving a combined total of 1,879 men.11 The participants were between 18 and 41 years of age and had mild to moderate hair loss (Hamilton stages III and IV). Two studies evaluated vertex baldness, while the third study assessed the anterior mid-scalp. None of these studies evaluated the effectiveness of finasteride in terms of bitemporal or frontal hair loss. After one year of therapy, patients treated with finasteride had an increase of 107 hairs in the number of hairs in a 1-in diameter of scalp compared with placebo. This difference resulted from an approximate 20-hair loss in the placebo group and a 90-hair increase in the treated group, compared with an average baseline count of 876 hairs. This 10 percent improvement is still below the normal density of 1,300 hairs per inch.11

The greatest benefit of finasteride may be in preventing further hair loss in men during the early stages of baldness. In this study11 only 17 percent of the treatment group showed hair loss, while 72 percent in the placebo group showed a progressive loss over the course of the 24-month trial.

In addition, in a study of 326 subjects, men with mild to moderate frontal thinning of the hair had a significant increase in hair counts in the frontal area, although most of the improvement was graded as “slight.” Unfortunately, no growth occurred in the temporal areas or on the hairline.12

In all of the above studies, evaluation also was performed by patient self-assessment, investigator assessment and independent expert examination of photographs. Subjective improvements in hair growth were noted in all three groups in all the studies.

Safety and Tolerability

Ten years after its introduction, minoxidil has been found to be well tolerated; the most frequently reported side effect is pruritis of the scalp. Initial concerns that the topical solution might affect blood pressure or cause other systemic effects have not been realized. As a result, both concentrations are available without a prescription.

Finasteride has been well tolerated in all studies, with a discontinuation rate similar to that of placebo. Sexual side effects were the most common, with 3.8 percent of the treated group experiencing decreased libido, erectile dysfunction or decreased volume of ejaculate, compared with 2.1 percent of the placebo group. Breast enlargement and tenderness, reported with use of the 5-mg dose, has not been reported with the 1-mg dose used to treat balding. Prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels may be lowered with chronic finasteride therapy, hampering the diagnostic value of the PSA test. Finasteride should not be used in women or children. It is a known teratogen, and the manufacturer recommends that the tablets not be taken or handled by pregnant women.

Finasteride affects DHT only in target tissues that contain the type II 5α-reductase enzyme and does not lower circulating levels of testosterone.13 As a result, patients taking the drug have no associated changes in muscle strength or bone density.

Dosage and Cost

Minoxidil is applied twice a day to dry scalp. Six sprays, or 1 mL of solution, should be applied. Overuse will not add benefit, and patients should be told not to expect an immediate response. The dosage of finasteride is 1 mg orally once daily. Cost information is given in Table 2.

| Agent | Dosage | Cost per month* | Cost per year* | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minoxidil 2% solution (Rogaine) | 6 sprays (1 mL, applied twice daily) | $25 (brand name) 13 (generic) | $300 (brand name) 156 (generic) | Appropriate for use in men and women; modest effectiveness | Ineffective for frontal hair loss. Localized skin effects. New hair is lost when treatment is discontinued. |

| Minoxidil 5% solution (Rogaine Extra Strength) | 6 sprays (1 mL, applied twice daily) | 30 (brand name) | 360 (brand name) | More effective than 2% solution | Ineffective for frontal hair loss. New hair is lost when treatment is discontinued. |

| Finasteride (Propecia), 1 mg | 1 mg orally once daily | 50 (brand name) | 600 (brand name) | Side effects uncommon; effective on vertex and anterior midscalp; oral dosing | For men only. New hair is lost when treatment is discontinued. May affect PSA levels. |

Counseling and Follow-up

These two modestly effective medical treatments for male pattern baldness appear to be safe. In counseling patients, it is important to communicate that effectiveness has primarily been demonstrated in younger men (18 to 41 years of age) and primarily in those with balding of the vertex. To date, treatment of frontal hair loss has been less successful. These drugs are most useful in preventing further hair loss, and regrowth of a full head of hair should not be expected.

With either medicine, six months of therapy may be necessary before the effects are apparent. Even with success, use of the product must continue indefinitely. At present, there is no way to predict which patients will respond to which treatment or whether one product is better suited to an individual patient. Some patients may prefer taking a tablet daily, while others may feel more comfortable applying a topical preparation. Since minoxidil is available without prescription, some patients may find this preparation to be more convenient. It is unlikely that insurance will pay for either medication, so cost may be a significant factor.

Further study is needed to determine long-term benefit with these two medications, as well as the benefit of their use in combination. With greater experience, it may become possible to predict those who will respond to treatment. These products may also prove useful in combination with other methods of treatment in male pattern baldness.