Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(7):2093-2100

A patient information handout on breast-feeding, written by the authors of this article.

The family physician can significantly influence a mother's decision to breast-feed. Prenatal support, hospital management and subsequent pediatric and maternal visits are all-important components of breast-feeding promotion. Prenatal encouragement increases breast-feeding rates and identifies potential problem areas. Hospital practices should focus on rooming-in, early and frequent breast-feeding, skilled support and avoidance of artificial nipples, pacifiers and formula. Infant follow-up should be two to four days postdischarge, with liberal use of referral and support groups, including lactation consultants and peer counselors.

Breast-feeding is the best form of nutrition for infants.1,2 Family physicians can have a significant impact on the initiation and maintenance of breast-feeding, if they have sufficient knowledge of breast-feeding benefits and the necessary clinical management skills or habits.3 In one recent study,4 only 25 percent of mothers reported discussing breast-feeding with health care professionals at the two-week visit. This same study demonstrated that encouragement by health professionals could have a significant impact on breast-feeding rates. Unfortunately, family physicians are no better than their peers in other specialties in promoting breast-feeding.5 In this article, we present strategies for the family physician to promote and support breast-feeding.

To effectively promote breast-feeding, the physician should educate all prospective mothers about the health benefits of breast-feeding as well as the risks associated with formula (Table 1).1–11 The protective benefits of breast-feeding are confirmed in studies performed in industrialized and developing countries, as well as across all socioeconomic strata.12 Discussing other concerns can also be useful in promoting breast-feeding (Tables 213–16 and 3).

| Illness | Relative risk |

|---|---|

| Allergies, eczema | 2 to 7 times1 |

| Urinary tract infections | 2.6 to 5.5 times6 |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 1.5 to 1.9 times7 |

| Diabetes, type 1 | 2.4 times8 |

| Gastroenteritis | 3 times1 |

| Hodgkin's lymphoma | 1.8 to 6.7 times9 |

| Otitis media | 2.4 times1 |

| Haemophilus influenzae meningitis | 3.8 times10 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 6 to 10 times2 |

| Pneumonia/lower respiratory tract infection | 1.7 to 5 times1 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus infection | 3.9 times2 |

| Sepsis | 2.1 times11 |

| Sudden infant death syndrome | 2.0 times1 |

| Industrialized-world hospitalization | 3 times1 |

| Developing-country morbidity | 50 times1 |

| Developing-country mortality | 7.9 times1 |

| Loss of freedom |

| Embarrassment |

| Jealousy (paternal and sibling) |

| Difficulty returning to work or school |

| Physical discomfort |

| Weaning |

| Lack of confidence (afraid that baby is starving) |

| Perception that formula is equal to breast milk |

Prenatal Care

HISTORY

Breast-feeding should be discussed at the first and subsequent prenatal visits. Most women will have made a decision about breast-feeding early in pregnancy.17 Breast-feeding education that is given repeatedly in person can have a significant influence on breast-feeding outcomes and appears to be superior to only postnatal support or only telephone support.18

The topic should be introduced with an open-ended statement such as, “Have you thought about how to feed your baby?” Tailor answers to the patient's background and use the opportunity to mention the risks associated with bottle-feeding (Table 1). Any history of early weaning or breast-feeding problems in previous pregnancies is predictive of future difficulty and should be discussed with the patient and noted on the prenatal record.19 A checklist that will ensure that all concerns are addressed should be an integral part of the prenatal record (Figure 1).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination is an opportunity to reassure the patient that her breasts are normal and that she will likely have no trouble producing enough milk. Inverted or flattened nipples can be ruled out by compressing below the areola to see if the nipple everts. Breast shells should not be used in the third trimester to promote correction of inverted nipples because their use has actually been shown to reduce the success of breast-feeding.20 In the same study, exercises to evert the nipples were shown to have no effect on breast-feeding success.

Potential problems should be noted on the prenatal record, along with a plan for consultation with a lactation specialist.

SUBSEQUENT PRENATAL VISITS

Support from a significant other has been identified as the most important factor for those who chose to bottle-feed.21 The patient's support person should be included in breast-feeding promotion efforts at every office visit. Knowing the mother's family and cultural background can assist the clinician in counseling the mother about breast-feeding.22 Women who are poor, less educated, less than 20 years of age or from a minority or immigrant background are less likely to choose to breast-feed. Whoever comes to the prenatal visits with the mother is likely to be important in her decision to breast-feed.

Positive messages about breast-feeding should be evident in the physician's office. Staff should be trained to provide basic breast-feeding help. Literature and posters that promote breast-feeding can be prominently displayed in the office. All magazines and literature in the waiting room can be examined to ensure that there are no unwanted advertisements or promotions of formula. A recent study23 showed that most physicians' offices distribute materials that violate the World Health Organization's International Code on the Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes (Table 4). A good source of materials that are available in English and other languages can be obtained from the local Women, Infants and Children (WIC) office, and examples are summarized in Table 5.

| AAP Breastfeeding Promotion in Pediatric Office Practices Program | |

| Telephone: 847-228-5005, extension 4779 | |

| Web site: http://www.aap.org/visit/brpromo.htm | |

| La Leche League | |

| Telephone: 847-519-7730 | |

| Web site: http://www.lalecheleague.org | |

| International Lactation Consultants Association | |

| Telephone: 919-787-5181 | |

| Web site: http://www.ilca.org | |

| Women, Infants and Children | |

| Telephone: 703-305-2746 | |

| Web site: http://ww.fns.usda.gov/wic/menu/contacts/coor/coor.htm | |

| AAFP breast-feeding support kit | |

| Telephone: 800-944-0000 | |

| Web site: https://www.aafp.org/catalog/patient/breastfeeding.html | |

| AAFP breast-feeding policy statement | |

| Telephone: 800-274-2237 | |

| Web site: https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/breastfeeding-support.html | |

Hospital Care

Hospital routines significantly affect breast-feeding.24 The World Health Organization (WHO), in conjunction with the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), has published a hospital breast-feeding policy called the Baby Friendly Initiative.25 The policy is intended for use in hospitals worldwide and is addressed to all personnel having patient-care responsibilities. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports this initiative and has published guidelines for the pediatrician that reiterate the same recommendations and expand on them.26 Although the American Academy of Family Physicians has a policy statement supporting breast-feeding, the group does not have published standards for the management of breast-feeding. The 12 recommendations in this article (Table 6) reinforce the guidelines from WHO and AAP, and are designed for the family physician to use during prenatal and postnatal care.

EARLY BREAST-FEEDING ATTEMPTS

New mothers should initiate breast-feeding as soon as possible after giving birth. When mothers initiate breast-feeding within one-half hour of birth, the baby's suckling reflex is strongest, and the baby is more alert.27 Early breast-feeding is associated with fewer nighttime feeding problems and better mother-infant communication.28 Babies who are put to breast earlier have been shown to have higher core temperatures and less temperature instability.29

NIPPLE CONFUSION

Nipple confusion occurs when a baby has not had the opportunity to establish the correct mouth movements for proper breast-feeding. Early and subsequent use of pacifiers, water, glucose water and formula supplementation have been shown to promote early weaning and nipple confusion.30,31 The frequent use of an artificial nipple early in life has been shown to promote a less effective mouth movement; this was demonstrated with ultrasonography over a decade ago.32 For this reason, the physician should encourage the staff and the patient to address breast-feeding problems first, with direct observation of breast-feeding, before considering the use of supplementation.

A woman with normal breasts produces sufficient colostrum during the last trimester and at delivery to sustain twins or a large term baby until her milk comes in. With few exceptions, studies1,30 have shown that formula samples in infant discharge packs shorten the duration of breast-feeding. For this reason, materials consistent with the WHO code33 should replace commercial discharge packs (Table 4).

BREAST-FEEDING ON DEMAND AND ROOMING-IN

Rooming-in and breast-feeding on demand should be an integral part of routine postpartum care. Breast-feeding “on demand” means feeding when the baby shows early signs of hunger, such as the rooting reflex, or when the baby is awake and his or her hands are coming to the mouth. Rooming-in allows mothers to respond to feeding cues much more effectively than a busy nurse could. Breast-feeding on demand promotes more frequent feeding, which prevents sore nipples, breast engorgement and early weaning.34

Supporting Breast-feeding Postpartum

EARLY PRENATAL FOLLOW-UP

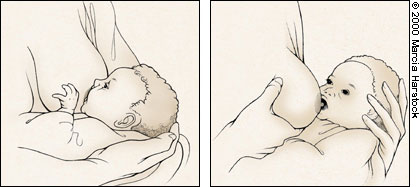

The AAP recommends a follow-up visit with an evaluation of breast-feeding at two to four days postdischarge for most newborns.26 Detailed questions can prevent unintended weaning. Inadvertent weaning can occur because suckling on the bottle is easier, and milk comes out faster. A decrease in milk supply because of decreased suckling at the breast further worsens the cycle. Anticipatory guidance (Table 7) that can help prevent this problem would include informing parents that growth spurts frequently occur at two to three weeks, three months and six months of age but can occur at any time. Witnessed breast-feeding is an important part of follow-up because many breast-feeding problems are caused by improper latch-on or positioning that can be detected and corrected35 (Figure 2).

| Feed the infant on demand—on “hunger cues.” |

| Listen and feel for infant's swallowing. |

| Infant should regain birth weight by two weeks of age. |

| Avoid nipple confusion by adopting this policy: three to four weeks of exclusive breastfeeding, then no more than one bottle a day, using expressed breast milk. |

| Count wet diapers: one on day 1, two on day 2, three on day 3, six per day from day 6 on, with three or more stools per day. |

| Report any signs and symptoms of dehydration and jaundice. |

| Make use of lactation support telephone numbers. |

| Expect weight loss of < 8 percent at the two- to four-day follow-up visit. |

TRACKING OF BREAST-FEEDING

Although attempts have been made to quantify breast-feeding effectiveness using an observer and a numerical score, the reliability of such tools versus electronic scale data has been questioned.36,37 A randomized controlled trial38 recently showed that weighing the infant can be accurate if an electronic scale is used. Mechanical scales are inadequate to this task. Care should be taken to weigh the baby wearing only a fresh diaper for the pre-feeding weight, with the same diaper being on the baby for the postfeeding weight.

The baby should be given credit for 20 calories per 30 g of weight gain, although breast milk can have higher caloric content, especially milk expressed for premature babies by their mothers.2 Babies should lose no more than 8 percent of their body weight after birth and should follow the appropriate weight curve thereafter (Table 8).

| Review prenatal breast-feeding checklist (see Figure 1). | |

| Note any changes from initial interview. | |

| Address any new concerns of the family. | |

| Ensure less than 8 percent loss from birth weight. | |

| Confirm appropriate weight gain: | |

| Regain birth weight by two weeks of age | |

| Acceptable weight gain of 10 g per kg per day (5 to 7 oz per week) is normal for the first 4 weeks. | |

| Observe breast-feeding. | |

| Inspect mother for sore nipples and examine infant. | |

REFERRAL TO LACTATION CONSULTANTS

Although prenatal education has been shown to affect the breast-feeding decision, in-hospital lectures alone do not measurably influence breast-feeding duration or satisfaction.39 What is more important to success is direct, one-on-one observation and assistance of the breast-feeding mother and child by a knowledgeable person, a certified lactation consultant40 or a peer counselor. Routine use of a lactation consultant after discharge in a general practice setting has been shown to be effective in prolonging breast-feeding.41

Referrals should be made for nearly all cases of severe nipple erosion, relactation, milk supply problems, failure to thrive, multiple infants, premature babies and any problem that does not respond quickly to support by the family physician. Certified lactation consultants have been shown to be of benefit in routine use with low-risk patients, whether measuring clinical outcome, patient satisfaction or costs.42 Referral sources are listed in Table 5.

BREAST-MILK EXPRESSION

Expressing breast milk is a skill that should be taught to all new mothers. Mothers should be encouraged to use only breast milk, not formula, when using bottles.

Bottle-feeding should be delayed for three to four weeks to prevent nipple confusion and early weaning.30 After this time, nipple confusion and premature weaning seem to be less of a problem if bottles are limited to about one per day.43 The clinician should routinely discuss bottle use and the issue of nipple confusion before discharge.

THE DECISION TO SUPPLEMENT

The decision to supplement should weigh the immediate clinical benefit with the long-term risks (Table 1). When the mother is available to feed the baby, the supplementation method used should simulate full breast-feeding as much as possible.2 With the baby at the breast during supplementation, nipple stimulation occurs, promoting better milk supply while preventing nipple confusion. The supplemental nursing system (Figure 3) and the periodontal syringe (Figure 4) allow the baby to be at the breast while supplementation is administered and are the preferred methods to use with the baby at the breast. Finger-, spoon- and cup-feeding are all alternatives to bottle-feeding that can be effectively used in the mother's absence.33 Before prescribing alternative feeding methods, the physician should ensure that the staff members employing them have been properly trained. If an infant is being fed by gavage, it is better to supplement by mixing breast milk with formula because the breast milk contains lipases that help with fat absorption.44 In some situations it may be impossible for the mother to breast-feed. Discussions should be supportive so as not to induce guilt or depression.

BANKED MILK

Banked milk should be considered when supplementation is necessary. Since the advent of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, banked milk is now pasteurized, and donors are screened for HIV, hepatitis and syphilis. Although a few biologically active components of human milk are lost in the pasteurization process, recent studies show minimal or no changes in such important components as fat content and antibacterial properties.45

SUBSEQUENT HOSPITALIZATION

When a mother or an infant is hospitalized, lactation should be continued if possible. At these times it is important to ask the mother in detail about her breast-feeding practices. Breast-feeding counseling when a baby is hospitalized for diarrhea has a positive effect on the rate of exclusive breast-feeding and prevents the continuation of diarrhea after discharge.18

We have found that a careful history taken during admission to the hospital can uncover unintended weaning. Lactation consultation during the hospitalization can help a mother resume later on.

Final Comment

Breast-feeding has proved to be superior to artificial supplements for medical, financial, social and psychologic reasons. Nevertheless, some patients and a few clinicians subscribe to the concept that formula is as good as breast milk, or at least that it is “good enough.” However, formula increases health risks to children when it unnecessarily replaces breast milk. The health care professional can play a key role in preventing illnesses by effectively supporting lactation.

The promotion and support of lactation should be a high priority for family physicians. To be effective in this effort, the clinician should focus on the issue from the preconception stage through pregnancy and delivery, and continue in subsequent infant care.