Am Fam Physician. 2000;61(10):3057-3064

Family physicians who are involved in the care of children are likely to encounter child abuse and should be able to recognize its common presentations. A history that is inconsistent with the patient's injuries is the hallmark of physical abuse. A pattern of physical findings, including bruises and fractures in areas unlikely to be accidentally injured, patterned bruises from objects, and circumferential burns or bruises in children not yet mobile, should be viewed as suspicious for child abuse. Family physicians who suspect physical abuse are mandated to make a report to the state child protective services agency and to assure the ongoing safety of the child.

Physical abuse of children in our society is a serious problem that has only recently been recognized by the medical community. The first published report in contemporary medical literature was in 1946,1 and the term “battered-child syndrome” was coined in 1962.2 Reports of child abuse are increasing as the medical profession gains experience in recognizing the signs and symptoms of physical abuse. Anyone involved in the care of children is likely to see children who have been physically abused. In 1996, approximately 1 million children were confirmed to be victims of maltreatment, and 1,185 children died from their injuries.3

The physician evaluating children who may have been abused is faced with special challenges. In addition to providing the diagnosis and treatment, the physician plays a new role when providing care for victims of physical abuse. In these cases, the physician must also ensure the child's safety and assist in the collection of evidence for possible litigation. The physician is mandated to report any suspected abuse to the state child protective services agency.

In the face of these new and often unaccustomed roles, hostile families may challenge physicians when the possibility of physical abuse is broached. Preconceived ideas regarding racial, cultural or economic norms as well as the strong feelings elicited when children may have been intentionally injured are confounding factors complicating the evaluation of suspected child abuse.

This article will review the physician's role in caring for children who are suspected victims of physical abuse. Typical features of the history, physical examination and focused laboratory and radiologic studies help physicians in diagnosing physical abuse in children. In addition, physicians caring for children must remain cognizant of the many medical conditions whose presentation can mimic signs of physical abuse.

History

The most important information leading to a diagnosis of physical abuse is obtained through the medical history. While perpetrators of child physical abuse and their victims come from all socioeconomic classes, certain factors place children at increased risk of physical abuse (Table 1).4 Adults who have been abused as children may become perpetrators of abuse as adults, although this is generally not the case.5

Children are commonly injured accidentally, and a history of age-appropriate injury, not witnessed, should not by itself raise the suspicion of child abuse. However, injury resulting from inappropriate supervision may raise the issue of neglect, a form of child abuse. When the patient's injuries are attributed to another child, the other child's developmental ability must be considered. A complicated and challenging scenario arises when the caregiver accuses an adult from whom the caregiver is divorced or separated as the perpetrator. In this case, the injury must be evaluated in the context of the history obtained from all those involved and from the physical examination.

The history of a child suspected to be abused should be elicited in a nonaccusatory manner. When possible, separate interviews should be held for the caregiver(s) and the child. The interviewer should inform the caregiver of the concern about abuse and the steps to be taken in the evaluation, including assurance regarding the child's safety and the possibility of a referral to the local child protective services agency. When the medical evaluation is inconsistent with the history provided by the child's caregiver, physical abuse should be seriously considered.

Physical Examination

Young children are commonly injured accidentally in the course of daily activities and play. However, the patterns of injuries seen in children who are physically abused differ from injuries seen in children who are hurt accidentally. The physical manifestations of nonaccidental trauma are varied and most commonly involve the skin, bone or central nervous system. Nonaccidental trauma may affect any organ system and mimic signs of accidental trauma or other disease processes. Table 3 presents patterns of physical findings that strongly suggest a diagnosis of physical abuse.

| Bruises on uncommonly injured body surfaces |

| Blunt-instrument marks or burns |

| Human hand marks or bite marks |

| Multiple injuries at different stages of healing |

| Evidence of poor care or failure to thrive |

| Circumferential immersion burns |

| Unexplained retinal hemorrhages |

The skin is the most commonly injured organ system and the easiest to examine. The location of bruises can sometimes be suggestive of accidental versus nonaccidental trauma. Children commonly fall and scrape or bruise the skin covering anterior parts of the body such as the shins, knees, hands, elbows, nose, periorbital area and forehead. Unexplained injuries to protected parts of the body such as the buttocks, thighs, torso, frenulum, ears and neck are suggestive of child abuse (Figure 1). The likelihood of having accidental bruises is a function of a child's behavior and developmental ability. Bruises are rare in infants who do not cruise or walk.7 The shape or pattern of injury may also suggest inflicted trauma. Bruises in the shapes of handprints, belt buckles, cord loops or encirclements represent child physical abuse7 (Figure 2).

The dating of bruises by color is advocated by medical textbooks and older literature on child abuse. The age of a bruise and the historical timing of an injury may have important legal implications for determining a perpetrator's identity. Determining the bruise's age by its color is a subjective step that does not take into account the individual patient's skin tone, the bruise's location (whether overlying soft tissue or bone), the patient's relative nutritional state or other indeterminate factors. When judging the age of a bruise, the physician may be better off making a rough estimate of the injury's date—within a day if the bruise is erythematous or older than a day if yellow or brown shades are present.8 The presence of bruises that have various ages may signify multiple episodes of injury caused by ongoing physical abuse (Figure 3).

Children may be abused by burning, which can result in disfiguring or fatal injuries. Cigarette burns leave centimeter-sized circular marks on the skin. Scald marks on the hands, feet or buttocks that have a glove, sock or circular appearance and spare the intertriginous areas are caused by deliberate immersion of the child in a sink or bathtub of hot water (Figure 4). It may be difficult to distinguish between an injury caused by scalding liquid thrown at the child from a burn resulting when a child accidentally tips a hot pan from a stove. The presence of excessive splash burns or of scalds on areas of the body not likely to get wet when a child spills a container of hot liquid suggests an inflicted injury.9

The physical examination should proceed carefully with inspection and palpation of all body surfaces. Specifically, all bruises and burns should be noted and described in terms of location, size, shape and color. Areas of tenderness may represent occult trauma and should be evaluated radiologically. Careful measurements should be taken and photographed. Photographs should include the patient's name, date of photograph and a measurement scale. It should be noted if bruises resemble a particular instrument pattern (e.g., belt buckle, cord).

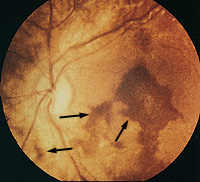

Careful attention should be paid to the oral cavity, groin and scalp for signs of occult trauma. The funduscopic examination is an often-overlooked part of the evaluation when physical abuse is suspected. Retinal hemorrhages (Figure 5) are highly suspicious for abuse resulting from “shaken-baby syndrome.”10 Infants who are forcibly shaken may present with unexplained injuries, seizures or a decreased level of consciousness. Nonspecific symptoms such as vomiting, irritability or abnormal respiration may be manifestations of abusive head injury. The diagnosis is easily overlooked and should be considered if facial or scalp bruises are present. In addition, the presence of xanthrochromic cerebrospinal fluid may indicate an old intracranial bleed.11

Radiologic Evaluation

The skeletal system may be injured in situations of child abuse or as a result of everyday activities. All fractures must be interpreted in the context of the child's developmental ability and the history of injury. For example, a transverse long-bone fracture in a three-month-old child is highly suspicious for physical abuse but may be unremarkable in an eight-year-old child. While any type of fracture can be the result of child abuse, certain fractures are much more specific for nonaccidental trauma. Fractures involving parts of the skeletal system or caused by mechanisms of injury unlikely to be from accidental trauma should be viewed with suspicion.

Table 4 ranks fractures by their specificity for child abuse.12 Uncommon fractures with a high specificity for being caused by nonaccidental trauma include metaphyseal “corner or bucket-handle” lesions, posterior rib fractures, scapular fractures, spinous process fractures and sternal fractures (Figures 6 and 7). Fractures with moderate specificity for nonaccidental trauma include multiple fractures, especially bilateral (Figure 8), fractures of different ages, epiphyseal separations, vertebral body fractures and subluxations, digital fractures and complex skull fractures. Common fractures with low specificity for abuse include clavicular fractures, long-bone shaft fractures and linear skull fractures.

| Likelihood of nonaccidental trauma | ||

|---|---|---|

| Low | Moderate | High |

| Clavicular fracture | Multiple fractures | Metaphyseal lesion |

| Long-bone shaft fracture | Epiphyseal separation | Posterior rib fracture |

| Linear skull fracture | Vertebral body fracture/subluxation | Scapular fracture |

| Digital fracture | Spinous process fracture | |

| Complex skull fracture | Sternal fracture | |

A complete skeletal survey is indicated in children younger than two years when physical abuse is suspected. Radiographs in a skeletal survey should minimally include single anteroposterior (AP) views of each extremity and the pelvis, as well as AP and lateral views of the chest and skull.13 Any abnormality seen should be viewed with at least two projections. A single “babygram” radiograph of the patient is diagnostically inadequate and should be avoided. The degree of healing seen on plain radiographs of fractures may also be useful for giving the injury an approximate age.

Specialized imaging may play a limited role in the evaluation of children with suspected physical abuse. Skeletal scintigraphy may be indicated when there is a high degree of suspicion for nonaccidental trauma but occult fractures are not seen on plain radiographs. A computed tomographic study of the head should be obtained in all children with suspected central nervous system injury.

Differential Diagnosis and Laboratory Evaluation

Evaluating suspected child abuse is a challenging task, and an incorrect diagnosis of child abuse can be as devastating to a family as the impact of missing a diagnosis of abuse can be to a child. A brief list of the many medical conditions that may mimic child abuse is given in Table 5.14 Several of these disorders may be distinguished from nonaccidental trauma by the other physical signs of the syndrome or by a natural history of the skin lesion that differs from that expected for an inflicted injury. Children with a history of easy bruising should receive a bleeding disorder screen consisting of a complete blood count, prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time and bleeding time. If the physician is still uncertain about the etiology of a finding suggestive of child abuse, referral to a subspecialist is indicated. It is important to remember that children with conditions whose presentation may mimic child abuse may also be victims of physical abuse.

| Hematologic | |

| Hemophilia | |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | |

| Von Willebrand's disease | |

| Henoch-Schönlein purpura | |

| Dermatologic | |

| Phytophotodermatitis | |

| Mongolian spots | |

| Vascular malformations | |

| Subcutaneous fat necrosis | |

| Infectious | |

| Bullous impetigo | |

| Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome | |

| Petechia or purpura from systemic bacterial or viral infections | |

| Metabolic congenital | |

| Osteogenesis imperfecta | |

| Ehlers-Danlos syndrome | |

| Rickets | |

| Insensitivity to pain disorders | |

| Accidental trauma | |

| Toddler's fracture | |

| Stress fracture | |

Management of Suspected Child Abuse

All 50 states have child-protection ordinances mandating that professionals who come in contact with children report cases of suspected abuse to the local child protective services agency. Making a report indicates that child abuse or neglect is a serious diagnostic consideration, not a definitive diagnosis. Each jurisdiction varies in terms of what constitutes abuse and the reporting mechanism. Physicians who care for children should familiarize themselves with the child protection statutes in the area in which they practice. The law requires reporting all cases of suspected, but not necessarily proven, abuse. Physicians who report their suspicions in good faith are protected from lawsuits. Information elicited during the course of a child abuse evaluation may potentially be used in a legal proceeding against the alleged perpetrator. Documentation in the medical record should be done with great care, because the record may become evidence in a criminal prosecution.

The physician caring for a child suspected of being physically abused must also make a determination, often in cooperation with the child protective services agency, regarding the safe disposition of the child. If the child cannot safely be sent home with a caregiver, the child may need to be admitted temporarily to a hospital and, in extreme cases, emergency custody of the child must be taken. Physical abuse in a child may indicate that other members of the household, particularly the mother, are also victims of domestic violence.15 The appropriate evaluation and safety of other family members must also be considered.

The evaluation of a child suspected of being physically abused is a common and serious problem for any physician who cares for children. A history inconsistent with the medical evaluation and certain patterns of physical findings should alert the examining physician to the possibility of child abuse. In addition to the traditional roles of diagnosis and treatment, the physician also has the responsibilities of evidence collection, alerting the child protective services agency and protecting the child.