A more recent article on diagnosis and treatment of melanoma is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2000;62(10):2277-2284

See related patient information handout on preventing melanoma, written by Amy S. Weichel, D.O.

In addressing the problem of malignant melanoma, family physicians should emphasize primary prevention. This includes educating patients about the importance of avoiding excessive sun exposure and preventing sunburns, and advising them about the importance of prompt self-referral for changing nevi. Family physicians should be able to perform an overall risk assessment for melanoma, particularly to identify persons with familial atypical mole syndrome. Patients with such high risk should be strongly considered for referral for dermatologic surveillance. Because there are no systematic studies in primary care populations, there are no data on which to base recommendations for periodic screening in this setting. However, when performing any part of the physical examination, family physicians should be alert for suspicious nevi. Nevi detected by the family physician or pointed out by the patient should be subject to excisional biopsy with accepted techniques or be referred for such a procedure.

The incidence of cutaneous malignant melanoma is increasing at an alarming rate. Over the past few decades, the increases in melanoma incidence and mortality have been among the greatest occurring with any cancer.1 The incidence and mortality rates from 1973 to 1994 rose 120 percent and 40 percent, respectively. In the United States, the lifetime risk of developing melanoma was projected to have increased to one in 75 by the year 2000, up from one in 87 in the 1990s.2

Another worrisome aspect is the frequency of malignant melanoma in the younger population. In the United States, the median age at diagnosis is 53, with about one in four new cases occurring in those younger than 40 years.3

Although there is some overlap between subtypes, there are primarily six subtypes of melanoma. Superficial spreading melanoma, nodular melanoma, lentigo maligna melanoma, acral lentiginous melanoma, amelanotic melanoma and desmoplastic melanoma account for 95 percent of all melanomas. Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common form, comprising 70 to 80 percent of all melanomas. The next two most common subtypes are nodular melanoma and acral lentiginous melanoma, which account for approximately 15 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

The prognosis for the patient with melanoma, however, is irrespective of the subtype and depends solely on the vertical depth of invasion (Table 1).4 Long-term survival in patients with metastatic disease is only 5 percent. Conversely, the prognosis for patients with early disease is excellent, and this stage is often curable with simple surgical excision. It is therefore critically important for family physicians to have a good understanding of the issues related to primary and secondary prevention and to promptly recognize atypical moles and melanoma.

Risk Stratification

The connection between sun exposure and melanoma is well known. Studies have shown that the prevalence of melanoma increases with proximity to the equator. Persons with skin types that are sensitive to the effects of ultraviolet radiation—red or blond hair, freckles and fair skin that burns easily and tans with difficulty—are at higher risk. Although cumulative sun exposure is linked to nonmelanoma skin cancer, intermittent intense sun exposure seems to be more related to melanoma risk.5

The important role of sun exposure in childhood was found in an immigration study from Australia, where rates of melanoma are the highest in the world. In this study,6 children who immigrated to Australia before the age of 10 had a risk similar to native-born Australians. Immigrants who arrived after the age of 15 had one fourth the rate of melanoma of native-born residents.

Other risk factors for melanoma include melanocytic precursor lesions (atypical moles), increased numbers of acquired nevi (more than 50), a family history of melanoma, a personal history of nonmelanoma skin cancer, giant congenital nevi (more than 20 cm) and immunosuppression. An estimated 5 to 10 percent of the population have atypical moles.3,7

A smaller subset of the population at particularly high risk for melanoma are those with “familial atypical mole syndrome” (dysplastic nevus syndrome). These people have at least one or two relatives with melanoma (first- or second-degree relatives) and frequently have more than 50 melanocytic nevi, some of which are atypical and often variable in size.3,7 Their relative risk for melanoma ranges from 33 to 1,269, with a cumulative lifetime risk approaching 100 percent.7,8 Table 29 summarizes the risk factors for melanoma.

Primary Prevention

Primary prevention consists of limiting exposure to sunlight and using sunscreens. Light-skinned persons should be informed of the importance of limiting sun exposure and avoiding sunburns; this advice is particularly important for children and teenagers. This recommendation is based on risk reduction because there is no direct evidence from randomized, controlled trials.3,10 Although the effectiveness of sunscreen use is less clear, a reasonable case has been made for people who cannot limit sun exposure.11 The concern about sunscreen use is that it may provide a false sense of security, and the user may spend excessive amounts of time in the sun.12 Table 3 lists the actions people can take to limit ultraviolet light exposure.

| Avoid the strong midday sun between the hours of 10 a.m. and 3 p.m. |

| When outdoors, seek out shaded areas. |

| Wear wide-brimmed hats (to protect the ears), long-sleeved shirts and long pants (tightly woven clothing is more protective). |

| Use a sunscreen with at least 15 SPF that protects against UVA and UVB light, reapplying the product every two to three hours and after sweating and swimming. |

| Do not use sunbeds or tanning salons. |

Although the data are not uniformly supportive, another important educational message is that patients should promptly seek medical attention when they notice a suspicious or changing nevus. Several studies have documented average patient delays of eight to 12 months after first noticing a changing nevus. In one study, 46 percent of patients with melanoma did not seek medical attention until they found ulceration, bleeding or a lump in the pigmented lesion, all late signs of melanoma.13

A campaign in Scotland to educate the population about the significance of suspicious and changing nevi resulted in an overall reduction in melanoma thickness as well as a trend toward decreased mortality in women.14 However, a more recent study15 suggested that shortening the time to diagnosis may not lead to a significant improvement in prognosis. These studies suggest that prognosis in a patient with melanoma depends on the tumor's inherent biologic aggressiveness as well as the time to diagnosis.

Secondary Prevention and Screening

Secondary prevention consists of routinely performing a total skin examination for a specific segment of the population. In theory, routine screening for melanoma could save lives because earlier detection of thinner tumors is associated with better survival rates. Screening can be performed on whole populations (population-based screening) or on subgroups of the population who are at higher risk for melanoma. Several organizations recommend routine screening solely for high-risk groups.3,10,12 Only the American Academy of Dermatology, the National Institutes of Health Consensus Conference on Early Melanoma and the American Cancer Society favor population-based screening in addition to screening for high-risk groups. However, there is no evidence to support population-based screening and, most importantly, there are no randomized, controlled trials.16

Screening of high-risk patients by dermatologists has yielded beneficial results. In one surveillance program,17 the mean thickness of initially detected index lesions was 1.44 mm, compared with 0.52 mm for surveillance melanomas. Additional studies show primary melanomas were more likely to be smaller and thinner when diagnosed during routine surveillance of high-risk patients.18,19 In a review of voluntary mass screening programs by the American Academy of Dermatology, persons at high risk for melanoma seem to be appropriately selecting themselves for screening. More than 86 percent of attendees had at least one risk factor for melanoma, and 78 percent had at least two risk factors.3 Follow-up data from 1992 to 1994 of this program showed that excised melanomas had a median thickness of 0.3 mm.

It is difficult to make any valid screening recommendations for primary care physicians based on studies performed by dermatologists. To our knowledge, no systematic studies have been performed in primary care populations related to the identification or surveillance of high-risk groups. It is not known what percentage of any given primary care practice would be at high risk. In addition, one study20 showed that although dermatologists may fail to make the clinical diagnosis of melanoma in 25 percent of cases, primary care physicians may fail to do so 40 percent of the time.

Therefore, the educational needs of primary care physicians must also be addressed to ensure a sufficiently accurate skin examination. The generally accepted methodology for effective screening tests requires evidence that the screening test is accurate and that early detection is beneficial to the patient. Possibly for these reasons, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening for melanoma by primary care physicians, and the Canadian Task Force recommends against it.

Identification and Excision of Suspicious Nevi

IDENTIFICATION

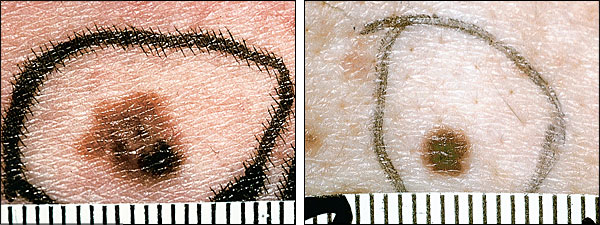

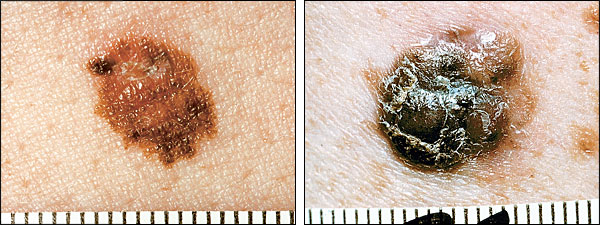

A review article has summarized a broad range of clinical and biologic data that support the validity of the dysplastic nevus concept.21 However, no universally accepted clinical criteria exist to allow precise distinction between normal and atypical nevi. In general, atypical moles (dysplastic nevi) are poorly circumscribed, variegated in color, usually 6 mm or larger, and predominantly macular. Atypical moles are a way of identifying patients at increased risk for melanoma, even outside the context of melanoma-prone families. The recognition of this class of atypical melanocytic lesions has permitted the formulation of a rational, biologically plausible model of melanocytic tumor progression.

Atypical moles are melanocytic lesions that are markers and precursors for melanoma. These moles represent a spectrum of lesions with varying degrees of severity rather than a distinct entity. Persons with sporadic atypical moles have an increased risk for melanoma that is proportional to the number of markers present.7 Anatomic studies have found that melanomas arise in areas with the greatest number of atypical moles. Results of studies attempting to delineate the percentage of melanomas arising from atypical moles have ranged from 7 to 70 percent. In one histologic study, atypical melanocytic hyperplasia was found in up to 23 percent of superficial spreading melanomas.22 In contrast, nodular melanoma is less associated with atypical moles, with only 3 percent of them showing histologic evidence of a coexisting nevus.

In settings where surveillance of high-risk patients is performed, the main goal is recognition and prompt removal of pigmented lesions that are clinically suspicious for melanoma or are changing in a worrisome manner. Many lesions that are removed will not prove to be malignant, but a significant proportion may be true melanoma precursors, and the removal of these moles interrupts tumor progression.

The chance of any one dysplastic nevus becoming malignant is small. Most, in fact, do not become malignant. Unfortunately, it is not possible to determine which lesions are destined to remain stable and which are destined to progress. It is also important to be aware of the possible significance of newly appearing melanocytic nevi after age 30. The natural history of melanocytic nevi is that their number increases from the age of six months to the third decade of life, after which they gradually decrease in number.7 So in high-risk persons older than 30 years, removal of any newly forming nevus should be considered. Finally, melanoma may arise from normal skin. Therefore, prophylactic removal of all nevi in high-risk patients does not diminish the need for continued surveillance and certainly represents excessive surgery in most cases.23 Figures 1 through 3 show examples of a dermal nevus, dysplastic nevi and malignant melanomas.

EXCISION

After identifying a suspicious lesion, a properly performed biopsy is essential. In the event that melanoma is diagnosed, the histologic interpretation of the biopsy will determine the prognosis and treatment plan. To date, no studies have evaluated or compared biopsy techniques for pigmented lesions. However, general recommendations include performing an excisional biopsy whenever possible.24 Accepted techniques for excisional biopsy include punch, saucerization and elliptic excision. Shave biopsy is not recommended. A shave biopsy will not miss a diagnosis of melanoma but may interfere with the staging process of determining the depth of invasion. In an excisional biopsy, the entire lesion with a narrow margin of normal-appearing tissue is excised. Wide excision is not recommended initially because it may prove to be unnecessary if the lesion is benign. If the lesion is too large for complete excision or is at a site where excision in total would be disfiguring, an incisional biopsy may be performed, in which only a portion of the lesion is removed. However, because only a portion of the lesion is sampled, the site of the biopsy must be chosen carefully. It may sometimes be necessary to sample several areas if the lesion is large and has morphologic variation.

Discussion

In addressing the problem of malignant melanoma, primary prevention should be a major focus for family physicians. Light-skinned patients need to be told about the dangers of sun exposure and sunburns, especially children and teenagers. Patients should also be made aware of the significance of changing nevi.

The most efficient way to impart this information is through mass media campaigns. However, family physicians should also be involved in patient education. Physicians can efficiently disseminate this information through brochures, posters and direct communication with patients. Posters and brochures can be placed in waiting and examination rooms. A good time to communicate with patients is during the physical examination, especially when atypical moles or large numbers of nevi are detected, or patients have susceptible skin types. Clearly, a patient who presents with a sunburn provides an excellent “teachable moment.” In light of physician time constraints and questions about the effectiveness of physician counseling, family physicians should focus on high-risk patients for individual discussions of primary prevention issues.

Secondary prevention in primary care is much more controversial because of the lack of systematic studies. Although there is no direct evidence, a good case can be made for referral of patients at the highest risk for melanoma for dermatologic surveillance. In patients at low to average (or possibly above average) risk, it may be sufficient to rely on primary prevention. What to do for patients who are above average to high risk depends, in part, on the individual physician's knowledge and experience with pigmented lesions, as well as the way the physician views secondary prevention issues. Referral of patients deemed to be at high risk is an option.

When performing any part of a physical examination, family physicians should be alert for suspicious nevi. It is helpful to be aware of the frequency of melanoma by body site in males and females (Figure 4).25 The trunk should be carefully inspected when the heart, lungs, abdomen and back are examined, particularly in male patients. Because more than one half of all melanomas in women occur on the legs, the gynecologic examination and fashions of summer provide the ideal time for opportunistic inspection of the skin. When atypical moles are detected, a decision will need to be made about excision. Clearly, benign atypical moles may be followed carefully, while more atypical nevi or lesions suspicious for melanoma should be excised using accepted techniques.